Esketamine

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Ketanest, Spravato, Vesierra, others |

| Other names | Esketamine hydrochloride; (S)-Ketamine; S(+)-Ketamine; JNJ-54135419 |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | NMDA receptor antagonist[1] |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Dependence risk | Low–moderate (physical); high (psychological)[1] |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | Intranasal[1] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a619017 |

| Legal | |

| License data |

|

| Legal status | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

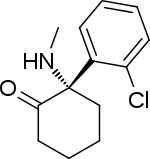

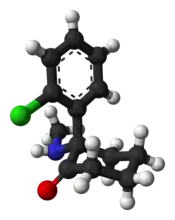

| Formula | C13H16ClNO |

| Molar mass | 237.73 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Esketamine, sold under the brand name Spravato among others, is a medication used for treatment-resistant depression or depression with acute thoughts of suicide.[1][4] It; however, appears to be less effective than ketamine.[6] It may also be used for anesthesia and pain.[7] It is used as a nasal spray or by intravenous injection.[1][7] In depression benefits generally occur within 24 hours.[1]

Common side effects include dissociation, dizziness, sedation, headache, anxiety, vomiting, and increased blood pressure.[1] Other side effects may include misuse.[4] The compound is the S(+) enantiomer of ketamine.[8] Use when breastfeeding is not recommended.[9] It primarily acts by blocking N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors.[1]

Esketamine came into medical use in Germany in 1997.[10][11] It was approved for medical use in the United States and Europe in 2019.[8][12] It is available as a generic medication.[13] In the United States the nasal spray costs about 5,500 to 7,900 USD for the first month of treatment as of 2021.[14][4] The intravenous formulation in the United Kingdom costs the NHS about £26 for 10 vials of 50 mg each.[7]

Medical uses

Depression

Similarly to ketamine, esketamine appears to be a rapid-acting antidepressant.[15][16] It is use in combination with an antidepressant in people with depression who had been unresponsive to treatment.[17][15][16][17][15][16] Of the five trials completed before approval in the US only two had favorable results.[18]

In February 2019, an outside panel of experts recommended that the FDA approve the nasal spray version of esketamine,[19] provided that it be given in a clinical setting, with people remaining on site for at least two hours after. The reasoning for this requirement is that trial participants temporarily experienced sedation, visual disturbances, trouble speaking, confusion, numbness, and feelings of dizziness during immediately after.[20]

It received a breakthrough designation from the FDA for treatment-resistant depression (TRD) in 2013 and major depressive disorder (MDD) with accompanying suicidal ideation in 2016.[17][16] In January 2020, esketamine nasal spray for depression was rejected by the National Health Service of Great Britain. NHS questioned the benefits with concerns it was too expensive. People who have been already using the medication were allowed to complete treatment if their doctors consider this necessary.[21]

Anesthesia

Esketamine is a general anesthetic and is used for similar indications as ketamine.[11] Such uses include induction of anesthesia in high-risk patients such as those with hemorrhagic shock, anaphylactic shock, septic shock, severe bronchospasm, severe hepatic insufficiency, cardiac tamponade, and constrictive pericarditis; anesthesia in caesarian section; use of multiple anesthetics in burns; and as a supplement to regional anesthesia with incomplete nerve blocks.[11]

Dosage

For depression it is used at an initial dose of 56 mg followed by 56 or 84 mg twice per week for the first 4 weeks.[4] After this it may be given weekly or every two weeks.[4]

It is used as a nasal spray or by intravenous injection.[1][7]

Side effects

Most common side effects when used in those with treatment resistant depression include dissociation, dizziness, nausea, sleepiness, anxiety, and increased blood pressure.[22]

Pharmacology

Esketamine is approximately twice as potent an anesthetic as racemic ketamine.[23] It is eliminated from the human body more quickly than arketamine (R(–)-ketamine) or racemic ketamine, although arketamine slows its elimination.[24]

A number of studies have suggested that esketamine has a more medically useful pharmacological action than arketamine or racemic ketamine but, in mice, that the rapid antidepressant effect of arketamine was greater and lasted longer than that of esketamine.[25] The usefulness of arketamine over esketamine has been supported by other researchers.[26][27][28]

Esketamine inhibits dopamine transporters eight times more than arketamine.[29] This increases dopamine activity in the brain. At doses causing the same intensity of effects, esketamine is generally considered to be more pleasant by patients.[30][31] Patients also generally recover mental function more quickly after being treated with pure esketamine, which may be a result of the fact that it is cleared from their system more quickly.[23][32] This is however in contradiction with R-ketamine being devoid of psychotomimetic side effects.[33]

Unlike arketamine, esketamine does not bind significantly to sigma receptors. Esketamine increases glucose metabolism in frontal cortex, while arketamine decreases glucose metabolism in the brain. This difference may be responsible for the fact that esketamine generally has a more dissociative or hallucinogenic effect while arketamine is reportedly more relaxing.[32] However, another study found no difference between racemic and (S)-ketamine on the patient's level of vigilance.[30] Interpretation of this finding is complicated by the fact that racemic ketamine is 50% (S)-ketamine.[34]

History

Esketamine was introduced for medical use as an anesthetic in Germany in 1997, and was subsequently marketed in other countries.[11][35] In addition to its anesthetic effects, the medication showed properties of being a rapid-acting antidepressant, and was subsequently investigated for use as such.[15][17] In November 2017, it completed phase III clinical trials for treatment-resistant depression in the United States.[15][17] Johnson & Johnson filed a Food and Drug Administration (FDA) New Drug Application (NDA) for approval on September 4, 2018;[36] the application was endorsed by an FDA advisory panel on February 12, 2019, and on March 5, 2019, the FDA approved esketamine, in conjunction with an oral antidepressant, for the treatment of depression in adults.[37]

In the 1980s and '90s, closely associated ketamine was used as a club drug known as "Special K" for its trip-inducing side effects.[38][39]

Society and culture

Names

Esketamine is the generic name of the drug and its INN and BAN, while esketamine hydrochloride is its BANM.[35] It is also known as S(+)-ketamine, (S)-ketamine, or (–)-ketamine ((-)[+] ketamine) as well as by its developmental code name JNJ-54135419.[35][17]

Esketamine is marketed under the brand name Spravato for use as an antidepressant and the brand names Ketanest, Ketanest S, Ketanest-S, Keta-S for use as an anesthetic (veterinary), among others.[35]

Availability

Esketamine is marketed as an antidepressant in the United States;[37] and as an anesthetic in the European Union.[35]

Legal status

Esketamine is a Schedule III controlled substance in the United States.[4]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Esketamine Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ↑ "Spravato 28 mg nasal spray, solution - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- ↑ "Vesierra 25 mg/ml solution for injection/infusion - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 21 February 2020. Archived from the original on 21 April 2021. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Spravato- esketamine hydrochloride solution". DailyMed. 6 August 2020. Archived from the original on 18 March 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- ↑ "Spravato EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 16 October 2019. Archived from the original on 23 November 2020. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- ↑ Bahji, A; Vazquez, GH; Zarate CA, Jr (15 February 2021). "Erratum to "Comparative efficacy of racemic ketamine and esketamine for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis" [Journal of Affective Disorders 278C (2021) 542-555]". Journal of affective disorders. 281: 1001. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.103. PMID 33229028.

- 1 2 3 4 BNF (80 ed.). BMJ Group and the Pharmaceutical Press. September 2020 – March 2021. p. 1411. ISBN 978-0-85711-369-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - 1 2 Commissioner, Office of the (24 March 2020). "FDA approves new nasal spray medication for treatment-resistant depression; available only at a certified doctor's office or clinic". FDA. Archived from the original on 23 July 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ↑ "Esketamine". Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed) [Internet]. 2019. PMID 31038855.

- ↑ Roche, Victoria; Zito, William S.; Lemke, Thomas; Williams, David A. (29 July 2019). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. PT1423. ISBN 978-1-4963-8587-1. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 Himmelseher S, Pfenninger E (December 1998). "[The clinical use of S-(+)-ketamine--a determination of its place]". Anasthesiologie, Intensivmedizin, Notfallmedizin, Schmerztherapie. 33 (12): 764–70. doi:10.1055/s-2007-994851. PMID 9893910.

- ↑ "Spravato". Archived from the original on 23 November 2020. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ↑ Ferrier, I. Nicol; Waite, Jonathan (4 July 2019). The ECT Handbook. Cambridge University Press. p. 150. ISBN 978-1-911623-16-8. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ↑ "Spravato Prices, Coupons & Patient Assistance Programs". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rakesh G, Pae CU, Masand PS (August 2017). "Beyond serotonin: newer antidepressants in the future". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 17 (8): 777–790. doi:10.1080/14737175.2017.1341310. PMID 28598698. S2CID 205823807.

- 1 2 3 4 Lener MS, Kadriu B, Zarate CA (March 2017). "Ketamine and Beyond: Investigations into the Potential of Glutamatergic Agents to Treat Depression". Drugs. 77 (4): 381–401. doi:10.1007/s40265-017-0702-8. PMC 5342919. PMID 28194724. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-07-08.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Esketamine - Johnson & Johnson - AdisInsight". Archived from the original on 5 September 2016. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- ↑ Wei, Yan; Chang, Lijia; Hashimoto, Kenji (March 2020). "A historical review of antidepressant effects of ketamine and its enantiomers". Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 190: 172870. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2020.172870.

- ↑ Koons C, Edney A (February 12, 2019). "First Big Depression Advance Since Prozac Nears FDA Approval". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on February 13, 2019. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

- ↑ Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee (PDAC) and Drug Safety and Risk Management (DSaRM) Advisory Committee (February 12, 2019). "FDA Briefing Document" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 13, 2019. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

Meeting, February 12, 2019. Agenda Topic: The committees will discuss the efficacy, safety, and risk-benefit profile of New Drug Application (NDA) 211243, esketamine 28 mg single-use nasal spray device, submitted by Janssen Pharmaceutica, for the treatment of treatment-resistant depression.

- ↑ "Anti-depressant spray not recommended on NHS". BBC News. 28 January 2020. Archived from the original on 3 February 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ↑ "Esketamine nasal spray" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 April 2019. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- 1 2 Himmelseher S, Pfenninger E (December 1998). "[The clinical use of S-(+)-ketamine--a determination of its place]". Anasthesiologie, Intensivmedizin, Notfallmedizin, Schmerztherapie (in Deutsch). 33 (12): 764–70. doi:10.1055/s-2007-994851. PMID 9893910.

- ↑ Ihmsen H, Geisslinger G, Schüttler J (November 2001). "Stereoselective pharmacokinetics of ketamine: R(–)-ketamine inhibits the elimination of S(+)-ketamine". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 70 (5): 431–8. doi:10.1067/mcp.2001.119722. PMID 11719729.

- ↑ Zhang JC, Li SX, Hashimoto K (January 2014). "R (-)-ketamine shows greater potency and longer lasting antidepressant effects than S (+)-ketamine". Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 116: 137–41. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2013.11.033. PMID 24316345. S2CID 140205448.

- ↑ Muller J, Pentyala S, Dilger J, Pentyala S (June 2016). "Ketamine enantiomers in the rapid and sustained antidepressant effects". Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology. 6 (3): 185–92. doi:10.1177/2045125316631267. PMC 4910398. PMID 27354907.

- ↑ Hashimoto K (November 2016). "Ketamine's antidepressant action: beyond NMDA receptor inhibition". Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets. 20 (11): 1389–1392. doi:10.1080/14728222.2016.1238899. PMID 27646666. S2CID 1244143.

- ↑ Yang B, Zhang JC, Han M, Yao W, Yang C, Ren Q, Ma M, Chen QX, Hashimoto K (October 2016). "Comparison of R-ketamine and rapastinel antidepressant effects in the social defeat stress model of depression". Psychopharmacology. 233 (19–20): 3647–57. doi:10.1007/s00213-016-4399-2. PMC 5021744. PMID 27488193.

- ↑ Nishimura M, Sato K (October 1999). "Ketamine stereoselectively inhibits rat dopamine transporter". Neuroscience Letters. 274 (2): 131–4. doi:10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00688-6. PMID 10553955. S2CID 10307361.

- 1 2 Doenicke A, Kugler J, Mayer M, Angster R, Hoffmann P (October 1992). "[Ketamine racemate or S-(+)-ketamine and midazolam. The effect on vigilance, efficacy and subjective findings]". Der Anaesthesist (in Deutsch). 41 (10): 610–8. PMID 1443509.

- ↑ Pfenninger E, Baier C, Claus S, Hege G (November 1994). "[Psychometric changes as well as analgesic action and cardiovascular adverse effects of ketamine racemate versus s-(+)-ketamine in subanesthetic doses]". Der Anaesthesist (in Deutsch). 43 Suppl 2: S68-75. PMID 7840417.

- 1 2 Vollenweider FX, Leenders KL, Oye I, Hell D, Angst J (February 1997). "Differential psychopathology and patterns of cerebral glucose utilisation produced by (S)- and (R)-ketamine in healthy volunteers using positron emission tomography (PET)". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 7 (1): 25–38. doi:10.1016/s0924-977x(96)00042-9. PMID 9088882. S2CID 26861697.

- ↑ Yang C, Shirayama Y, Zhang JC, Ren Q, Yao W, Ma M, Dong C, Hashimoto K (September 2015). "R-ketamine: a rapid-onset and sustained antidepressant without psychotomimetic side effects". Translational Psychiatry. 5 (9): e632. doi:10.1038/tp.2015.136. PMC 5068814. PMID 26327690.

- ↑ Pezeshkian, Melody (2021-02-15). "The Nuances of Ketamine's Neurochemistry". Psychedelic Science Review. Archived from the original on 2021-02-15. Retrieved 2021-02-16.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Esketamine". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 2017-08-29. Retrieved 2021-07-08.

- ↑ "Janssen Submits Esketamine Nasal Spray New Drug Application to U.S. FDA for Treatment-Resistant Depression". Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Archived from the original on 2020-08-14. Retrieved 2021-07-08.

- 1 2 "FDA approves new nasal spray medication for treatment-resistant depression; available only at a certified doctor's office or clinic". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). Archived from the original on 2021-07-23. Retrieved 2019-03-06.

- ↑ Marsa, Linda (January 2020). "A Paradigm Shift for Depression Treatment". Discover. Kalmbach Media.

- ↑ Hoffer, Lee (7 March 2019). "The FDA Approved a Ketamine-Like Nasal Spray for Hard-to-Treat Depression". Vice. Archived from the original on 20 April 2020. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

External links

| External sites: |

|

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |

- "Esketamine hydrochloride". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-07-08.