Nabilone

| |

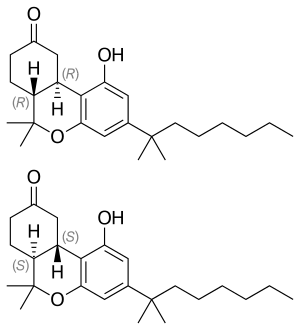

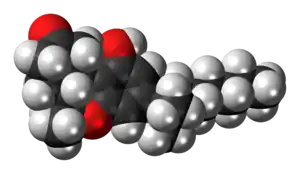

Top: (R,R)-(−)-nabilone, Center: (S,S)-(+)-nabilone, Bottom: Space-filling model of (R,R)-(−)-nabilone | |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Cesamet, Canemes |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Synthetic cannabinoid[1] |

| Main uses | Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting[1] |

| Side effects | Sleepiness, dry mouth, dizziness, feeling high, poor coordination, headache[1] |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth (capsules) |

| Typical dose | 1 to 2 mg BID[2] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a607048 |

| Legal | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 20% after first-pass by the liver |

| Protein binding | similar to THC (±97%) |

| Elimination half-life | 2 hours, with metabolites around 35 hours |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C24H36O3 |

| Molar mass | 372.549 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Nabilone, sold under the brand name Cesamet among others, is a medication used for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting.[1] Some evidence supports modest effectiveness for fibromyalgia and multiple sclerosis.[3][4] It is taken by mouth.[2]

Common side effects include sleepiness, dry mouth, dizziness, feeling high, poor coordination, and headache.[1] Other side effects may include fast heart rate, abuse, and psychosis.[1] Safety in pregnancy is unclear.[1] It is a synthetic cannabinoid which effects similar to tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the primary psychoactive compound found in Cannabis.[1][5]

Nabilone was approved for medical use in the United States in 1985.[1] In the United Kingdom 20 pills of 1 mg costs the NHS about £200 as of 2021.[2] This amount in the United States costs about 820 USD.[6] In the United States it is a schedule II controlled substance.[1]

Medical uses

Nabilone is used to treat nausea and vomiting in people under chemotherapy.[7][8]

Nabilone has shown modest effectiveness in relieving fibromyalgia.[3] A 2011 review of cannabinoids for chronic pain determined there was evidence of safety and modest efficacy for some conditions.[9]

A study comparing nabilone with metoclopramide, conducted before the development of modern 5-HT3 antagonist anti-emetics such as ondansetron, revealed that patients taking cisplatin chemotherapy preferred metoclopramide, while patients taking carboplatin preferred nabilone to control nausea and vomiting.[10][11]

Nabilone is sometimes used for nightmares in post-traumatic stress disorder, but there have not been studies longer than nine weeks, so effects of longer-term use are not known.[12]

Dosage

It is started at 1 mg twice per day and may be increased to 2 mg twice per day.[2]

Side effects

Nabilone can increase – rather than decrease – postoperative pain. In the treatment of fibromyalgia, adverse effects limit the useful dose.[3] Side effects of nabilone include, but are not limited to: dizziness/vertigo, euphoria, drowsiness, dry mouth, ataxia, sleep disturbance, dysphoria, headache, nausea, disorientation, depersonalization, and asthenia.[7]

Pharmacology

Pharmacokinetics

Nabilone is given in 1 or 2 mg doses multiple times a day up to a total of 6 mg. It is completely absorbed from oral administration and highly plasma protein bound. Multiple cytochrome P450 enzymes extensively metabolize nabilone to various metabolites that have not been fully characterized.[7]

Chemistry

Nabilone is a racemic mixture consisting of (S,S)-(+)- and (R,R)-(−)-isomers.

History

Nabilone was originally developed by Eli Lilly and Company; Lilly received FDA approval in 1985 to market it, but withdrew that approval in 1989 for commercial reasons.[13] Valeant Pharmaceuticals acquired the rights from Lilly in 2004.[13] Valeant tried and failed to get the medication approved in 2005[14] and then succeeded in 2006.[13]

In 2007, Valeant acquired the United Kingdom and European Union rights to market nabilone from Cambridge Laboratories.[15]

Nabilone was approved in Austria to treat chemotherapy-induced nausea in 2013; it was already approved in Spain for the same indication and was legal in Belgium to treat glaucoma, spasticity in multiple sclerosis, wasting due to AIDS, and chronic pain.[16]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Nabilone Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 BNF 81: March-September 2021. BMJ Group and the Pharmaceutical Press. 2021. p. 451. ISBN 978-0857114105.

- 1 2 3 Fine PG, Rosenfeld MJ (2013). "The endocannabinoid system, cannabinoids, and pain". Rambam Maimonides Medical Journal (Review). 4 (4): e0022. doi:10.5041/RMMJ.10129. PMC 3820295. PMID 24228165.

- ↑ Nielsen S, Germanos R, Weier M, Pollard J, Degenhardt L, Hall W, Buckley N, Farrell M (February 2018). "The Use of Cannabis and Cannabinoids in Treating Symptoms of Multiple Sclerosis: a Systematic Review of Reviews". Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports. 18 (2): 8. doi:10.1007/s11910-018-0814-x. hdl:2123/18910. PMID 29442178. S2CID 3375801.

- ↑ "DailyMed - CESAMET- nabilone capsule". dailymed.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 25 March 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ↑ "Cesamet Prices, Coupons & Patient Assistance Programs". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 9 April 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- 1 2 3 "Nabilone label" (PDF). FDA. May 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-04-02. Retrieved 2021-03-03.

- ↑ "Nabilone Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC) - (eMC)". UK Electronic Medicines Compendium. August 2014. Archived from the original on 2017-12-22. Retrieved 2021-03-03.

- ↑ Lynch ME, Campbell F (November 2011). "Cannabinoids for treatment of chronic non-cancer pain; a systematic review of randomized trials". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 72 (5): 735–44. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.03970.x. PMC 3243008. PMID 21426373.

- ↑ Cunningham D, Bradley CJ, Forrest GJ, Hutcheon AW, Adams L, Sneddon M, Harding M, Kerr DJ, Soukop M, Kaye SB (April 1988). "A randomized trial of oral nabilone and prochlorperazine compared to intravenous metoclopramide and dexamethasone in the treatment of nausea and vomiting induced by chemotherapy regimens containing cisplatin or cisplatin analogues". European Journal of Cancer & Clinical Oncology (Randomized controlled trial). 24 (4): 685–9. doi:10.1016/0277-5379(88)90300-8. PMID 2838294.

- ↑ Smith LA, Azariah F, Lavender VT, Stoner NS, Bettiol S (November 2015). "Cannabinoids for nausea and vomiting in adults with cancer receiving chemotherapy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (11): CD009464. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009464.pub2. PMC 6931414. PMID 26561338.

- ↑ "Long-term Nabilone Use: A Review of the Clinical Effectiveness and Safety". CADTH Rapid Response Reports. Oct 2015. PMID 26561692. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-03-03.

- 1 2 3 "Valeant returns synthetic cannabinoid to USA". Pharma Times. 17 May 2006. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ↑ "FDA turns down Valeant's anti-nausea drug". Pharma Times. 3 January 2006. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ↑ "Cambridge Labs divests nabilone to Valeant - Pharmaceutical industry n". The Pharma Letter. February 27, 2007. Archived from the original on November 18, 2016. Retrieved March 3, 2021.

- ↑ "Cannabis Laws & Scheduling in Europe - MedicalMarijuana.eu". MedicalMarijuana.eu. Archived from the original on 18 November 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

External links

| Identifiers: |

|---|