Pentazocine

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Trade names | Talwin, others | ||

| Other names | Pentazocine hydrochloride, pentazocine lactate | ||

| Clinical data | |||

| Drug class | Opioid[1] | ||

| Main uses | Moderate to severe pain[1] | ||

| Side effects | Fizziness, felling high, sleepiness, nausea, seizures, respiratory depression[1] | ||

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ | ||

| Pregnancy category |

| ||

| Routes of use | By mouth, IV, IM | ||

| Onset of action | By mouth: 15 min[2] | ||

| Duration of action | At least 3 hrs[1] | ||

| External links | |||

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph | ||

| Legal | |||

| Legal status |

| ||

| Pharmacokinetics | |||

| Bioavailability | ~20% by mouth | ||

| Metabolism | Liver | ||

| Elimination half-life | 2 to 3 hours | ||

| Excretion | Kidney | ||

| Chemical and physical data | |||

| Formula | C19H27NO | ||

| Molar mass | 285.431 g·mol−1 | ||

| 3D model (JSmol) | |||

SMILES

| |||

InChI

| |||

Pentazocine, sold under the brand name Talwin among others, is a opioid used to treat moderate to severe pain.[1] It may be taken by mouth or used by injection.[1] Onset of effects begin with 30 min when taken by mouth and last for more than 3 hours.[1] It is generally a less preferred medication.[3]

Common side effects include dizziness, felling high, sleepiness, and nausea.[1] Other side effects may include seizures, abuse, insufficient breathing (respiratory depression), serotonin syndrome, and adrenal insufficiency.[1] It should not be used in people with opioid dependence as may precipitate opioid withdrawal.[3] It is a partial agonist of the opioid receptor.[1]

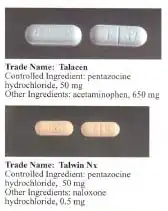

Pentazocine was patented in 1960 and approved for medical use in 1964.[4] It is available as a generic medication.[3] In the United States 120 tablets of 50 mg costs about 80 USD as of 2021.[5] This amount in the United Kingdom costs the NHS about £12o.[3] The tables come combined with naloxone to try to decrease misuse.[1]

Medical use

Pentazocine is used primarily to treat pain, although its analgesic effects are subject to a ceiling effect.[6] It has been discontinued by its corporate sponsor in Australia, although it may be available through the special access scheme.[7]

Dosage

For pain it is generally taken at 50 mg every 4 hours.[1] Doses may be increased to 100 mg every 4 hours.[1]

Side effects

Side effects are similar to those of morphine, but pentazocine, due to its action at the kappa opioid receptor is more likely to invoke psychotomimetic effects.[6] High dose may cause high blood pressure or high heart rate.[7] It may also increase cardiac work after myocardial infarction when given intravenously and hence this use should be avoided where possible.[7] Respiratory depression is a common side effect, but is subject to a ceiling effect, such that at a certain dose the degree of respiratory depression will no longer increase with dose increases.[7] Likewise rarely it has been associated with agranulocytosis, erythema multiforme and toxic epidermal necrolysis.[7]

Injection sites

Injection site necrosis and sepsis has occurred (sometimes requiring amputation of limb) with multiple injection of pentazocine lactate. In addition, animal studies have demonstrated that Pentazocine is tolerated less well subcutaneously than intramuscularly.[8]

Mechanism of action

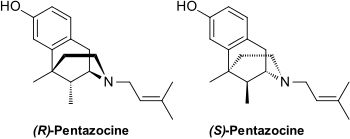

It is believed to work by activating (agonizing) κ-opioid receptors (KOR) and μ-opioid receptors (MOR). As such it is called an opioid as it delivers its effects on pain by interacting with the opioid receptors. It, unlike most other opioids, subject to a ceiling effect, which is when at a certain dose (which differs from person-to-person) no more pain relief, or side effects, is obtained by increasing the dose any further.[7] Chemically it is classed as a benzomorphan and it comes in two enantiomers, which are molecules that are exact (non-superimposable) mirror images of one another.

History

Pentazocine was developed by the Sterling Drug Company, Sterling-Winthrop Research Institute, of Rensselaer, New York. The analgesic compound was first made at Sterling in 1958. U.S. testing was conducted between 1961 and 1967.It was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in June 1967 after being favorably reviewed following testing on 12,000 patients in the United States. By mid 1967 Pentazocine was already being sold in Mexico, England, and Argentina, under different trade names.[9]

Society and culture

Recreational use

In the 1970s, recreational drug users discovered that combining pentazocine with tripelennamine (a first-generation ethylenediamine antihistamine most commonly dispensed under the brand names Pelamine and Pyribenzamine) produced a euphoric sensation. Since tripelennamine tablets are typically blue in color and brand-name Pentazocine is known as Talwin (hence "Ts"), the pentazocine/tripelennamine combination acquired the slang name Ts and blues. After health-care professionals and drug-enforcement officials became aware of this scenario, the mu-opioid-antagonist naloxone was added to oral preparations containing pentazocine to prevent perceived "misuse" via injection,[10] and the reported incidence of its recreational use has declined precipitously since.

Legal status

Pentazocine was originally unclassified under the Controlled Substances Act. A petition was filed with the Drug Enforcement Administration on October 1, 1971, to shift it to Schedule III. The petition was filed by Joseph L. Fink III, a pharmacist and law student at Georgetown University Law Center as part of the course Lawyering in the Public Interest. That petition was accepted for review on November 10, 1971.[11] D.E.A. published a Final Rule transferring it to schedule IV on January 10, 1979, with an effective date of February 9, 1979.[12] This is understood to be the first instance of a successful petition to reclassify a substance under the relatively recently enacted Controlled Substances Act. Pentazocine is still classified in Schedule IV under the Controlled Substances Act in the United States, even with the addition of Naloxone. Some states classify it in Schedule II, such as Illinois[13] and South Carolina (injectable form only),[14] or Schedule III such as Kentucky.[15]) Internationally, pentazocine is a Schedule III drug under the Convention on Psychotropic Substances.[16] Pentazocine has a DEA ACSCN of 9720; being a Schedule IV substance, the DEA does not assign an annual manufacturing quota for pentazocine for the United States.

Brand names

Pentazocine is sold under several brand names, such as Fortral, Sosegon, Talwin NX (with naloxone), Talwin, Talwin PX, Fortwin and Talacen (with paracetamol (acetaminophen)).

Research

In an open-label, add-on, single-day, acute-dose small clinical study, pentazocine was found to rapidly and substantially reduce symptoms of mania in individuals with bipolar disorder that were in the manic phase of the condition.[17] It was postulated that the efficacy observed was due to κ-opioid receptor activation-mediated amelioration of hyperdopaminergia in the reward pathways.[17] Minimal sedation and no side effects including psychotomimetic effects or worsening of psychosis were observed at the dose administered.[17]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "Pentazocine Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 23 February 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ↑ Stitzel RE (2004). Modern pharmacology with clinical applications (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 325. ISBN 9780781737623. Archived from the original on 2021-10-21. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

- 1 2 3 4 BNF 81: March-September 2021. BMJ Group and the Pharmaceutical Press. 2021. p. 489. ISBN 978-0857114105.

- ↑ Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 527. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 2021-08-29. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

- ↑ "Pentazocine / Naloxone Prices, Coupons & Savings Tips - GoodRx". GoodRx. Archived from the original on 14 June 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- 1 2 Joint Formulary Committee (2013). British National Formulary (BNF) (65 ed.). London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. ISBN 978-0-85711-084-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Brayfield A, ed. (9 January 2017). "Pentazocine". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. Archived from the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ↑ "TALWIN (pentazocine lactate) injection, solution". DailyMed. National Institute of Health. Archived from the original on 2014-02-01. Retrieved 2011-12-10.

- ↑ Pain-Killing Drug Approved By F.D.A., New York Times, June 27, 1967, pg. 41.

- ↑ "Pentazocine and Naloxone tablets". DailyMed. National Institute of Health. Archived from the original on 2012-04-06. Retrieved 2011-12-10.

- ↑ 36 Fed.Reg. 217. November 1971. Archived from the original on 2021-10-21. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

- ↑ 44 Fed. Reg. 2169. 1979. Archived from the original on 2021-10-21. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

- ↑ "Illinois Controlled Substances Act". Illinois General Assembly. Archived from the original on 2020-10-29. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

- ↑ "South Carolina DHEC Controlled Substance Schedule". South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control. Archived from the original on 2018-09-01. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

- ↑ "Kentucky Scheduled Drug List" (PDF). Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-01-31. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

- ↑ "List of psychotropic substances under international control" (PDF). Green List - Annex to the annual statistical report on psychotropic substances (form P) (27th ed.). International Narcotics Control Board. 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-04-21. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

- 1 2 3 Chartoff EH, Mavrikaki M (2015). "Sex Differences in Kappa Opioid Receptor Function and Their Potential Impact on Addiction". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 9: 466. doi:10.3389/fnins.2015.00466. PMC 4679873. PMID 26733781.

External links

| Identifiers: |

|---|

-pentazocine3DanJ.gif)

-pentazocine3DanJ.gif)