Meprobamate

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

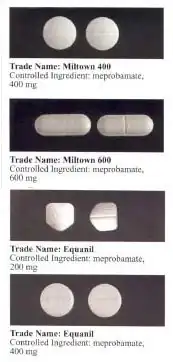

| Trade names | Miltown, Equanil, Meprospan, others |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Carbamate[1] |

| Main uses | Anxiety, seizures[2] |

| Side effects | Nausea, palpitations, low blood pressure, sleepiness, poor coordination, aplastic anemia[2] |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth |

| Onset of action | Within an hour[2] |

| Typical dose | 400 mg TID to QID[2] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682077 |

| Legal | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | ? |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 10 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C9H18N2O4 |

| Molar mass | 218.250 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Density | 1.229 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 105 to 106 °C (221 to 223 °F) |

| Boiling point | 200 °C (392 °F) to 210 °C (410 °F) |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Meprobamate, sold under the brand name Miltown among others, is a medication used to treat anxiety and seizures, as well as for sedation.[2] It is taken by mouth.[2] Effects begin within an hour.[2] Evidence only supports short term use.[2]

Common side effects include nausea, palpitations, low blood pressure, sleepiness, poor coordination, and aplastic anemia.[2] Other side effects may include abuse and allergic reactions.[2] Use in pregnancy may harm the baby.[2] It is a carbamate.[1]

Meprobamate's medical use was discovered in 1905.[3] Its approval was withdrawn in Europe in 2012.[4] It is available as a generic medication.[5] In the United States it costs about 160 USD per month as of 2021.[6] In the United Kingdom it is only available by special order and is deemed to be a less suitable medication.[7]

Medical uses

Meprobamate is used for the short-term relief of anxiety, although whether the purported antianxiety effects of meprobamate are separable from its sedative effects is not known. Its effectiveness as a selective agent for the treatment of anxiety has not been proven in humans,[8] and is not used as often as the benzodiazepines for this purpose.

Meprobamate, like barbiturates, possesses an analgesic/anesthetic potential. It is also found as a component of the combination analgesic Stopayne capsules (along with paracetamol (acetaminophen), caffeine, and codeine phosphate).

Dosage

It is generally taken at a dose of 400 mg three to four times per day.[2]

Meprobamate is available in 200- and 400-mg tablets for oral administration. It is also a component of the combination drug Equagesic (discontinued in the UK in 2002), acting as a muscle relaxant.

Side effects

Symptoms of meprobamate overdose include drowsiness, headache, sluggishness, unresponsiveness, or coma; loss of muscle control; severe impairment or cessation of breathing; or shock.[9] Death has been reported with ingestion of as little as 12 g of meprobamate and survival with as much as 40 g. In an overdose, meprobamate tablets may form a gastric bezoar, requiring physical removal of the undissolved mass of tablets through an endoscope; therefore, administration of activated charcoal should be considered even after 4 or more hours or if levels are rising.[10]

Health issues

Meprobamate is a Schedule IV drug (US) (S5 in South Africa) under the Convention on Psychotropic Substances. With protracted use, it can cause physical dependence and a potentially life-threatening abstinence syndrome similar to that of barbiturates and alcohol (delirium tremens). For this reason, discontinuation is often achieved through an extended regimen of slowly decreasing doses over a period of weeks or even months. Alternatively, the patient may be switched to a longer-acting gabaergic agent such as diazepam (in a manner similar to the use of methadone therapy for opiate addiction) before attempting detitration.

While an acute cerebral edema is widely believed to be the cause of actor and martial artist Bruce Lee's death in 1973, another factor which may have contributed to Lee’s death, was his decision to take Equagesic (a brand which combined meprobamate and aspirin).[11]

"In the January 2008 issue of Drug Safety Update, a stop press article announced the recent European review of carisoprodol for which the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use concluded that the risks of treatment outweigh the benefits. This review was triggered by concerns from the Norwegian Medical Agency that carisoprodol (converted to meprobamate after administration) was associated with increased risk of abuse, addiction, intoxication, and psychomotor impairment." February 2008.[12]

The European Medicines Agency recommended suspension of marketing authorisations for meprobamate-containing medicines in the European Union in January 2012.

Pharmacology

Although it was marketed as being safer, meprobamate has most of the pharmacological effects and dangers of barbiturates and acts at the barbiturate binding site (though it is less sedating at effective doses). It is reported to have some anticonvulsant properties against absence seizures, but can exacerbate generalized tonic-clonic seizures.

Meprobamate's mechanism of action is not completely known. It has been shown in animal studies to have effects at multiple sites in the central nervous system, including the thalamus and limbic system. Meprobamate binds to GABAA receptors[13][14] which interrupts neuronal communication in the reticular formation and spinal cord, causing sedation and altered perception of pain. Meprobamate has the ability to activate currents even in the absence of GABA.[13] This relatively unique property makes meprobamate exceptionally dangerous when used in combination with other GABA-mediated drugs (including alcohol). It is also a potent adenosine reuptake inhibitor.[15][16] Related drugs include carisoprodol and tybamate (prodrugs of meprobamate), felbamate, mebutamate, and methocarbamol.

History

Frank Berger was working in a laboratory of a British drug company, looking for a preservative for penicillin, when he noticed that a compound called mephenesin calmed laboratory rodents without actually sedating them.[17] Berger subsequently referred to this “tranquilizing” effect in a now-historic article, published by the British Journal of Pharmacology in 1946. However, three major drawbacks existed to the use of mephenesin as a tranquilizer: a very short duration of action, greater effect on the spinal cord than on the brain, and a weak activity.[18]

In May 1950, after moving to Carter Products in New Jersey, Berger and a chemist, Bernard John Ludwig, synthesized a chemically related tranquilizing compound, meprobamate, that overcame these three drawbacks.[19] Wallace Laboratories, a subsidiary of Carter Products, bought the license and named their new product "Miltown" after the borough of Milltown, New Jersey. Launched in 1955, it rapidly became the first blockbuster psychotropic drug in American history, becoming popular in Hollywood and gaining fame for its seemingly miraculous effects.[20] It has since been marketed under more than 100 trade names, from Amepromat through Quivet to Zirpon.[21]

A December 1955 study of 101 patients at the Mississippi State Hospital in Whitfield, Mississippi, found meprobamate useful in the alleviation of "mental symptoms": 3% of patients made a complete recovery, 29% were greatly improved, 50% were somewhat better, while 18% realized little change. Self-destructive patients became cooperative and calmer, and experienced a resumption of logical thinking. In 50% of the cases, relaxation brought about more favorable sleep habits. Following the trial, hydrotherapy and all types of shock treatment were subsequently halted.[22] Meprobamate was found to help in the treatment of alcoholics by 1956.[23] By 1957, over 36 million prescriptions had been filled for meprobamate in the US alone, a billion pills had been manufactured, and it accounted for fully a third of all prescriptions written.[24] Berger, clinical director of Wallace Laboratories, described it as a relaxant of the central nervous system, whereas other tranquilizers suppressed it. A University of Michigan study found that meprobamate affected driving skills. Though patients reported being able to relax more easily, meprobamate did not completely alleviate their tense feelings. The disclosures came at a special scientific meeting at the Barbizon Plaza Hotel in New York City, at which Aldous Huxley addressed an evening session. He predicted the development of many chemicals "capable of changing the quality of human consciousness", in the next few years.[25]

Meprobamate was one of the first drugs to be widely advertised to the general public, with user Milton Berle promoting the drug heavily on his television show, calling himself 'Uncle Miltown'.[26] Miltown soon became ubiquitous in 1950s American life, with 1 in 20 Americans having used it by late 1956,[27] and popular comedians making as many jokes about the drug as they did about Elvis Presley.[28]

In January 1960, Carter Products, Inc. and American Home Products Corporation (which marketed meprobamate as Equanil) were charged with having conspired to monopolize the market in mild tranquilizers. It was revealed that the sale of meprobamate earned $40,000,000 for the defendants. Of this amount, American Home Products accounted for about two-thirds and Carter about one-third. The U.S. government sought an order mandating that Carter make its meprobamate patent available at no charge to any company desiring to use it.[29]

In April 1965, meprobamate was removed from the list of tranquilizers when experts ruled that the drug was a sedative, instead. The U.S. Pharmacopoeia published the ruling. At the same time, the Medical Letter disclosed that meprobamate could be addictive at doses not much above recommended.[30] In December 1967, meprobamate was placed under abuse control amendments to the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act. Records on production and distribution were required to be kept. Limits were placed on prescription duration and refills.[31]

Production continued throughout the 1960s, but by 1970, meprobamate was listed as a controlled substance after it was discovered to cause physical and psychological dependence.

On January 19, 2012, the European Medicines Agency withdrew marketing authorization in the European Union for all medicines containing meprobamate, "due to serious side effects seen with the medicine." The Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use "concluded that the benefits of meprobamate do not outweigh its risks."[4] In October 2013, Canada also withdrew marketing authorization.[32]

It was the best-selling minor tranquilizer for a time, but has largely been replaced by the benzodiazepines due to their wider therapeutic index (lower risk of toxicity at therapeutically prescribed doses) and lower incidence of serious side effects.

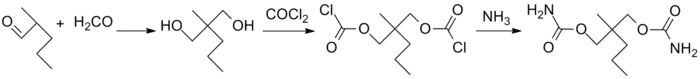

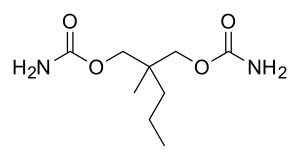

Synthesis

Meprobamate, 2-methyl-2-propyl-1,3-propanediol dicarbamate is synthesized by the reaction of 2-methylvaleraldehyde with two molecules of formaldehyde and the subsequent transformation of the resulting 2-methyl-2-propylpropan-1,3-diol into the dicarbamate via successive reactions with phosgene and ammonia.

See also

- Mother's Little Helper (song)

References

- 1 2 Maronde, Robert F. (6 December 2012). Topics in Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 420. ISBN 978-1-4612-4864-4. Archived from the original on 16 November 2021. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Meprobamate Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 31 December 2019. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ↑ Wallace, Edwin R.; Gach, John (13 April 2010). "History of Psychiatry and Medical Psychology: With an Epilogue on Psychiatry and the Mind-Body Relation". Springer Science & Business Media. Archived from the original on 16 November 2021. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- 1 2 "Questions and answers on the suspension of the marketing uthorisations for oral meprobamate-containing medicines" (PDF). 2012-01-19. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-12-21. Retrieved 2012-01-20.

- ↑ "Meprobamate Prices, Coupons & Savings Tips - GoodRx". GoodRx. Archived from the original on 14 November 2016. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ↑ "Meprobamate Prices, Coupons & Savings Tips - GoodRx". GoodRx. Archived from the original on 14 November 2016. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ↑ BNF 81: March-September 2021. BMJ Group and the Pharmaceutical Press. 2021. p. 365. ISBN 978-0857114105.

- ↑ Brunton L, Lazo J, Parker K (2005-10-28). Goodman And Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (11 ed.). McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-142280-2. Archived from the original on 2013-12-31. Retrieved 2021-09-03.

- ↑ "livertox.nlm.nih.gov -Meprobamate , overview". Archived from the original on 2019-08-28. Retrieved 2021-09-03.

- ↑ Allen MD, Greenblatt DJ, Noel BJ (December 1977). "Meprobamate overdosage: a continuing problem". Clinical Toxicology. 11 (5): 501–15. doi:10.3109/15563657708988216. PMID 608316.

- ↑ Molloy T (20 July 2018). "How Did Bruce Lee Die? New Book Has a Sad, Strange Explanation (Podcast)". The Wrap. Archived from the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ↑ "Carisoprodol and meprobamate: risks outweigh benefits". Gov.UK. February 2008. Archived from the original on 2014-12-22. Retrieved 2021-09-03.

- 1 2 Rho JM, Donevan SD, Rogawski MA (March 1997). "Barbiturate-like actions of the propanediol dicarbamates felbamate and meprobamate". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 280 (3): 1383–91. PMID 9067327. Archived from the original on 2020-07-03. Retrieved 2021-09-03.

- ↑ Kumar M, Dillon GH (March 2016). "Assessment of direct gating and allosteric modulatory effects of meprobamate in recombinant GABA(A) receptors". European Journal of Pharmacology. 775: 149–58. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2016.02.031. PMC 4806799. PMID 26872987.

- ↑ Phillis JW, Delong RE (June 1984). "A purinergic component in the central actions of meprobamate". European Journal of Pharmacology. 101 (3–4): 295–7. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(84)90174-2. PMID 6468504.

- ↑ DeLong RE, Phillis JW, Barraco RA (December 1985). "A possible role of endogenous adenosine in the sedative action of meprobamate". European Journal of Pharmacology. 118 (3): 359–62. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(85)90149-9. PMID 4085561.

- ↑ Healy D (2003). Let them eat prozac. Toronto: J. Lorimer & Co. p. 27. ISBN 978-1550287837. OCLC 52286331. Archived from the original on 2021-10-30. Retrieved 2021-09-03.

- ↑ Berger FM (December 1947). "The mode of action of myanesin". British Journal of Pharmacology and Chemotherapy. 2 (4): 241–50. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1947.tb00341.x. PMC 1509790. PMID 19108125.

- ↑ Ludwig BJ, Piech E (1951). "Some anticonvulsant agents derived from 1, 3-propanediol". J Am Chem Soc. 73 (12): 5779–5781. doi:10.1021/ja01156a086.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ↑ Tone A (2009). "The Fashionable Pill". The Age of Anxiety: A History of America's Turbulent Affair with Tranquilizers. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-08658-0. Archived from the original on 2021-10-30. Retrieved 2021-09-03.

- ↑ "Meprobamate". NIST Chemistry WebBook, SRD 69. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Archived from the original on 2018-06-30. Retrieved 2021-09-03.

- ↑ Laurence WL (28 December 1955). "New Hope Arises On Cancer Serum". The New York Times. p. 21. Archived from the original on 24 July 2018. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ↑ "ALCOHOLIC PERIL FOUND IN DRUGS; Some Tranquilizing Therapy May Be Habit-Forming, Physicians Tell Parley". The New York Times. 1956-04-01. p. 28. Archived from the original on 2012-10-19. Retrieved 2009-01-23.

- ↑ Dokoupil T (2009-01-22). "How Mother Found Her Helper". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 2009-12-03. Retrieved 2009-01-23.

- ↑ "'BEHAVIOR' DRUGS NOW ENVISIONED; Aldous Huxley Predicts They Will Bring Re-Examining of Ethics and Religion". The New York Times. 1956-10-19. Archived from the original on 2016-08-17. Retrieved 2009-02-01.

- ↑ 1964-, Tone, Andrea (2009). The age of anxiety : a history of America's turbulent affair with tranquilizers. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 9780786727476. OCLC 302287405.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Miltown: a game-changing drug you've probably never heard of | CBC Radio". CBC. Archived from the original on 2018-09-22. Retrieved 2018-09-22.

- ↑ Ingersoll, Elliott; Rak, Carl (2015). Psychopharmacology for Mental Health Professionals: An Integrative Approach. Cengage Learning. p. 129. ISBN 9781305537231.

- ↑ Ranzal E (1960-01-28). "TRUST SUIT NAMES 2 DRUG CONCERNS; Makers of Tranquilizers Are Accused". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2012-10-19. Retrieved 2009-02-01.

- ↑ "MILTOWN OFF LIST OF TRANQUILIZERS; But It Will Continue to Be Used as a Sedative". The New York Times. 1965-04-22. Archived from the original on 2018-07-09. Retrieved 2009-02-01.

- ↑ "Tranquilizer Is Put Under U.S. Curbs; Side-Effects Noted". The New York Times. 1967-12-06. Archived from the original on 2018-07-09. Retrieved 2009-02-01.

- ↑ "282 MEP (meprobamate-containing medicine) - Market Withdrawal, Effective October 28, 2013 - For Health Professionals". Health Canada. Archived from the original on September 20, 2020. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- ↑ US granted 2724720, Berger FM, Ludwig BJ, "Dicarbamates of substituted propane diols", issued 22 December 1955, assigned to Carter Products Inc.

- ↑ CH granted 373026, Fries FA, Moenkemeyer K, "Verfahren zur Herstellung von 2-Methyl-2-propyl-propandiol-1,3", issued 15 November 1963, assigned to Huels Chemische Werke AG

- ↑ Ludwig BJ, Piech EC (1951). "Some Anticonvulsant Agents Derived from 1,3-Propanediols". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 73 (12): 5779–5781. doi:10.1021/ja01156a086.

External links

| Identifiers: |

|---|

- List of psychotropic substances under international control.

- The Comparative Toxicogenomics Database: Meprobamate Archived 2012-04-02 at the Wayback Machine.

- RxList.com - Meprobamate