Club drug

Club drugs, also called rave drugs, or party drugs are a loosely defined category of recreational drugs which are associated with discothèques in the 1970s and nightclubs, dance clubs, electronic dance music (EDM) parties, and raves in the 1980s to today.[1][2][3] Unlike many other categories, such as opiates and benzodiazepines, which are established according to pharmaceutical or chemical properties, club drugs are a "category of convenience", in which drugs are included due to the locations they are consumed and/or where the user goes while under the influence of the drugs. Club drugs are generally used by adolescents and young adults.[2][4] This group of drugs is also called "designer drugs", as most are synthesized in a chemical lab (e.g., MDMA, ketamine, LSD) rather than being sourced from plants (as with marijuana, which comes from the cannabis plant) or opiates (which are naturally derived from the opium poppy).[5]

Club drugs range from entactogens such as MDMA ("ecstasy"), 2C-B ("nexus") and inhalants (e.g., nitrous oxide and poppers) to stimulants (e.g., amphetamine and cocaine), depressants/sedatives (Quaaludes, GHB, Rohypnol) and psychedelic and hallucinogenic drugs (LSD, magic mushrooms and DMT). Dancers at all-night parties and dance events have used some of these drugs for their stimulating properties since the 1960s Mod subculture in U.K., whose members took amphetamine to stay up all night. In the 1970s disco scene, the club drugs of choice shifted to the stimulant cocaine and the depressant Quaaludes. Quaaludes were so common at disco clubs that the drug was nicknamed "disco biscuits". In the 1990s and 2000s, methamphetamine and MDMA are sold and used in many clubs. "Club drugs" vary by country and region; in some regions, even opiates such as heroin and morphine have been sold at clubs, though this practice is relatively uncommon.[6] Narconon states that other synthetic drugs used in clubs, or which are sold as "Ecstasy" include harmaline; piperazines (e.g., BZP and TFMPP); PMA/PMMA; mephedrone (generally used outside the US) and MDPV.[7]

The legal status of club drugs varies according to the region and the drug. Some drugs are legal in some jurisdictions, such as "poppers" (which are often sold as "room deodorizer" or "leather polish" to get around drug laws) and nitrous oxide (which is legal when used from a whipped cream can). Other club drugs, such as amphetamine or MDMA are generally illegal, unless the individual has a lawful prescription from a doctor. Some club drugs are almost always illegal, such as cocaine.

There are a range of risks from using club drugs. As with all drugs, from legal drugs like alcohol to illegal drugs like BZP, usage can increase the risk of injury due to falls, dangerous or risky behavior (e.g., unsafe sex) and, if the user drives, injury or death due to impaired driving accidents. Some club drugs, such as cocaine and amphetamines, are addictive, and regular use can lead to the user craving more of the drug. Some club drugs are more associated with overdoses. Some club drugs can cause adverse health effects which can be harmful to the user, such as the dehydration associated with MDMA use in an all-night dance club setting.[8]

Types

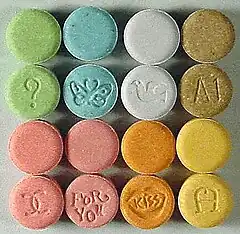

Ecstasy

MDMA (ecstasy) is a popular club drug in the rave and electronic dance music scenes and in nightclubs. It is known under many nicknames, including "e" and "Molly". MDMA is often considered the drug of choice within the rave culture and is also used at clubs, festivals, house parties and free parties .[9] In the rave environment, the sensory effects from the music and lighting are often highly synergistic with the drug. The psychedelic quality of MDMA and its amphetamine-like energizing effect offers multiple reasons for its appeal to users in the rave setting. Some users enjoy the feeling of mass communion from the inhibition-reducing effects of the drug, while others use it as "party fuel" for all-night dancing.[10]

MDMA is taken by users less frequently than other stimulants, typically less than once per week.[11] Effects include "[g]reater enjoyment of dancing", "[d]istortions of perceptions, particularly light, music and touch"; and "[a]rtificial feelings of empathy and emotional warmth".[7] MDMA is sometimes taken in conjunction with other psychoactive drugs, such as LSD, DMT, psilocybin mushrooms and 2C-B. Users sometimes use mentholated products while taking MDMA for its cooling sensation.[12]

Stimulants

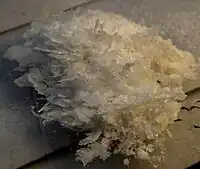

A number of stimulants are used as club drugs. Various amphetamines and methamphetamines are used as stimulants, as is cocaine. These drugs enable clubgoers to dance all night. Cocaine is a powerful nervous system stimulant.[13] Its effects can last from fifteen or thirty minutes to an hour. The duration of cocaine's effects depends on the amount taken and the route of administration.[14] Cocaine can be in the form of fine white powder, bitter to the taste. When inhaled or injected, it causes a numbing effect. Cocaine increases alertness, feelings of well-being and euphoria, energy and motor activity, feelings of competence and sexuality. Cocaine's stimulant effects are similar to that of amphetamine, however, these effects tend to be much shorter lasting and more prominent.

Depressants/sedatives

Methaqualone (Quaaludes) became increasingly popular as a recreational drug in the late 1960s and 1970s, known variously as "ludes" or "sopers" (also "soaps") in the U.S. and "mandrakes" and "mandies" in the UK, Australia and New Zealand. The drug was often used by hippies and by people who went dancing at glam rock clubs in the 1970s and at discos (one slang term for Quaaludes in the disco era was "disco biscuits"). In the mid-1970s, there were bars in Manhattan called "juice bars" that only served non-alcoholic drinks that catered to people who liked to dance on methaqualone.[15] Purported methaqualone is in a significant minority of cases found to be inert, or contain diphenhydramine or benzodiazepines. Methaqualone is one of the most commonly used recreational drugs in South Africa.[16][17] It is also popular elsewhere in Africa and in India.[17] Commonly known as Mandrax, M-pills, buttons, or smarties, a mixture of crushed mandrax and cannabis is smoked, usually through a smoking pipe made from the neck of a broken bottle.[18]

The depressant GHB (also used by assailants as a date rape drug, in which case they slip it into a victim's drink) is intentionally taken by some users as a party drug and club drug.

Rohypnol (also used as a date rape drug) is a sedative/hypnotic that causes intoxication and impairs cognitive functions. This may appear as lack of concentration, confusion and anterograde amnesia. It can be described as a hangover-like effect which can persist to the next day.[19] It also impairs psychomotor functions similar to other benzodiazepines and nonbenzodiazepine hypnotic drugs.[20]

The previously mentioned selection of drugs are generally categorized as club drugs by the media and the United States government, this distinction probably does not have an accurate correlation to real usage patterns. For example, alcoholic beverages (beer, wine, hard liquor) is generally not included under the category of club drugs, even though it is probably used more than any other drug at clubs, particularly those that are liquor-licensed nightclubs or bars.

Psychedelic drugs

A psychedelic drug is a medication whose primary action is to alter cognition and perception, typically by agonising serotonin receptors,[21] causing thought and visual/auditory changes, and heightened state of consciousness.[22] Major psychedelic drugs include Bufotenin, Racemorphan, LSD, DMT, and psilocybin mushrooms.

Not to be confused with psychoactive drugs, such as stimulants and opioids, which induce states of altered consciousness, psychedelics tend to affect the mind in ways that result in the experience being qualitatively different from those of ordinary consciousness. Whereas stimulants cause an energized feeling and opiates produce a dreamy, relaxed state, the psychedelic experience is often compared to non-ordinary forms of consciousness such as trance, meditation, yoga, religious ecstasy, dreaming and even near-death experiences. With a few exceptions, most psychedelic drugs fall into one of the three following families of chemical compounds; tryptamines, phenethylamines, and lysergamides. Many psychedelic drugs are illegal worldwide under the UN conventions unless used in a medical or religious context. Despite these regulations, recreational use of psychedelics is common, including at raves and EDM concerts and festivals.

Inhalants

"Poppers" are small bottles of volatile drugs which are inhaled by clubgoers for the "rush" or "high" that they can create. Nitrites such as alkyl nitrite originally came as small glass capsules that were popped open, which led to the nickname "poppers." The drug became popular in the US first on the disco/club scene of the 1970s, where dancers used the drug for the "rush" it provides, and because it was perceived to enhance the experience of dancing to loud, bass-heavy disco. The drug became popular again in the mid-1980s and 1990s rave and EDM scenes. As with disco clubgoers, rave participants and EDM enthusiasts used the drug because its "rush" or "high" was perceived to enhance the experience of dancing to pulsating music and lights.

Nitrous oxide is a dissociative inhalant that can cause depersonalisation, derealisation (feeling like the world is not real), dizziness, euphoria, and some sound distortion (flanging).[23] In some cases, it may cause slight hallucinations and have a mild aphrodisiac effect. While medical grade nitrous oxide is only available to dentists and other licensed health care providers, recreational users often obtain the drug by inhaling the nitrous oxide used in whipped cream aerosol cans. Nitrous oxide users also buy small "whippet" canisters of nitrous oxide intended for use in restaurant whipped cream dispensers and then "crack" open these canisters to inhale the gas. Users typically transfer the gas to a plastic bag or balloon prior to inhaling it.

Ketamine

Ketamine, a dissociative anesthetic, has a long history of being used in clubs and was one of the most popular substances used in the New York Club Kid scene. Ketamine produces a dissociative state, characterized by a sense of detachment from one's physical body and the external world which is known as depersonalization and derealization. Effects include hallucinations, changes in the perception of distances, relative scale, color and durations/time, as well as a slowing of the visual system's ability to update what the user is seeing.

Other

In the 2000s, synthetic phenethylamines such as 2C-I, 2C-B and DOB have been referred to as club drugs due to their stimulating and psychedelic nature (and their chemical relationship with MDMA).[24] By late 2012, derivates of the psychedelic 2C-X drugs, the NBOMes and especially 25I-NBOMe, had become common at raves in Europe. The drug organization Norconon states that other synthetic drugs used in clubs, or which are sold as "Ecstasy" include harmaline; piperazines (e.g., BZP and TFMPP); PMA/PMMA; mephedrone (generally used outside the US) and MDPV.[7]

Though far less common than other "club drugs" like MDMA, ketamine, or LSD, heroin can be found in some of New York City's clubs. Marijuana and related cannabis products are used by some clubgoers; for example, some Rohypnol and ketamine users mix the powdered drug with marijuana and smoke it.[7]

Effects

Desired effects

Although each club drug has different effects, their use in clubs reflects their perceived contribution to the user's experience dancing to a beat as lights flash to the music. Club drug users are generally taking the drugs to "enhance social intimacy and sensory stimulation" from the dance club experience.[25] Some club drugs' popularity stems from their ability to induce euphoria, lowered inhibition and an intoxicated feeling. Some drugs, such as amphetamine and cocaine, give the dancer hyperactivity and energy to dance all night. Many drugs produce a feeling of heightened physical sensation, and increased libido and sexual pleasure. Some club drugs, such as LSD, DMT, MDMA, 2C-B and ketamine enhance the experience of being in a nightclub with pulsating lights and flashing lasers and throbbing dance music, because they cause hallucinations or unusual perception effects.

Risks and adverse effects

Although research continues into the full scope of the effects of illegal drugs, regular and unsafe use of club drugs is widely accepted to have damaging side effects and carry a risk of addiction. Increased heart rate, a steep increase in body temperature, increase in blood pressure, spasms and dehydration are all common side effects of MDMA and methamphetamine. Breathing and respiratory issues, drowsiness, nausea and confusion are common side effects of said drugs. They can also make the user anxious, stressed and panicked, or even hallucinate. Withdrawal is also a risk with many club drugs. Drug cravings as the chemical leaves the user's body can be complicated by sleep deprivation, dehydration and hypoglycaemia to result in debilitating 'come downs' which can result in depression-like symptoms. In the worst instance, club drugs result in the death of the user from cardiac arrest or water intoxication due to the increase in heart rate and thirstiness induced. Inconsistency in the strength and exact composition of the supplied drug causing users to overdose. Wide variance in the measured rate of deaths caused by drugs such as ecstasy across countries suggest that user and societal/environmental factors may also affect the lethality of club drugs.

Drug interactions

Another risk is drug interactions. Some club drug users take multiple drugs at the same time.[26] "Club drugs often are taken together, with alcohol, or with other drugs to enhance their effect."[25] Drug interactions can cause hazardous side effects. When club drug users are in a liquor-licensed nightclub, users may mix pills or powders (MDMA, 2C-B, GHB, ketamine) with consumption of alcoholic drinks such as beer, wine or hard liquor. Some depressants, such as Rohypnol, are dangerous to take while drinking alcohol. "Ketamine often is taken in "trail mixes" of methamphetamine, phencyclidine, cocaine, sildenafil citrate (Viagra), morphine or heroin."[25]

Injury or death due to risky behaviour

Another risk with club drugs is one shared by all drugs, from legal drugs like alcohol to abused over-the-counter drugs (taking large amounts of dextromethorphan cough syrup) and illegal drugs (BZP, amphetamines, etc.): while impaired, the user is more likely to be injured, engage in dangerous or risky behaviour (e.g., unsafe sex) or, if she or he drives, have an accident resulting in injury or death due to impaired driving.

Misrepresentation

In many cases, illegal club drugs are misrepresented.[25] That is, a dealer will tell a purchaser that she/he has a certain illegal drug for sale, while in fact the dealer's pills, capsules or bags of powder do not contain that chemical. For example, MDMA ("ecstasy") is very hard to synthesize in illegal underground labs, and methamphetamine is much easier (it can be made from household chemicals and over-the-counter cold remedies containing pseudoephedrine). As such, what dealers sell as MDMA is often methamphetamine powder. Similarly, pills sold by drug dealers as LSD, a drug which only the top chemists have the training to synthesize, most often contain no LSD; instead, they often contain PCP, a veterinary tranquilizer which produces dissociation and hallucinations in humans. In some cases, the dealer has intentionally substituted a less expensive, more available illegal drug for another drug. In other cases, the substitution was made by a higher-level drug cartel or organization, and the dealer may in fact believe that the bogus product is MDMA or LSD.

"Cutting", adulteration and "spiking"

With the exception of marijuana, which typically is uncut and unlaced, many illegal drugs, especially those which come in a powder or pill form are "cut" with other substances or "spiked" with other drugs. Cocaine, amphetamines and other stimulants often have caffeine powder added, as this increases the dealer's profit by bulking out the powder, so that less expensive cocaine or amphetamine has to be used in making the product. Some substances used to "cut" illegal drugs are not inherently harmful, as they are just used to "pad" or "bulk out" a quantity of the illegal drug and increase profits, such as lactose (milk sugar), a white powder often added to heroin. Even fairly innocuous powders that are added to illegal drugs, though, can have adverse effects with some routes of illegal drug administration, such as injection. With some drugs, adulterants are sometimes added to make the product more appealing. For example, "flavoured cocaine" has flavoured powder added to the drug.

Whereas the main goal of "cutting" is to bulk out a quantity of pure, expensive illegal drugs with an innocuous and not overly harmful substance (lactose) or fairly low-impact product (e.g., caffeine in amphetamine pills), the goal of "spiking" is to try to make lower-quality illegal drug or a lower-potency source of illegal drugs give the user the type of "high" or psychedelic experience she or he is seeking. While it was earlier stated that marijuana is most often uncut and un-spiked, some dealers add PCP to marijuana (this is nicknamed "wet marijuana"), because adding this dissociative psychedelic to low-grade, low-THC marijuana can convert it into a cannabis that creates striking hallucinogenic effects. Drug researchers learned that some dealers were spiking marijuana when they tested US teens who stated that they had only used a single illegal drug (marijuana) and the teens tested positive for marijuana and PCP. Some dealers who have a very small quantity of MDMA powder to sell "spike" it with less expensive and easier to produce methamphetamine powder.

- Street cocaine is often adulterated or "cut" with talc, lactose, sucrose, glucose, mannitol, inositol, caffeine, procaine, phencyclidine, phenytoin, lignocaine, strychnine, amphetamine, or heroin.[27]

- A common methamphetamine adulterant is dimethyl sulfone, a solvent and cosmetic base without known effect on the nervous system; other adulterants include dimethylamphetamine HCl, ephedrine HCl, sodium thiosulfate, sodium chloride, sodium glutamate, and a mixture of caffeine with sodium benzoate.[28]

Addiction

Not all club drugs are addictive (e.g. nitrous oxide). However, some club drugs are addictive. Amphetamine heavily used in recreational fashion pose a risk of addiction.[29]

Cocaine addiction is a psychological desire to use cocaine regularly. Cocaine overdose may result in cardiovascular and brain damage, such as: constricting blood vessels in the brain, causing strokes and constricting arteries in the heart; causing heart attacks.[30] The use of cocaine creates euphoria and high amounts of energy. If taken in large, unsafe doses, it is possible to cause mood swings, paranoia, insomnia, psychosis, high blood pressure, a fast heart rate, panic attacks, cognitive impairments and drastic changes in personality. The symptoms of cocaine withdrawal (also known as comedown or crash) range from moderate to severe: dysphoria, depression, anxiety, psychological and physical weakness, pain, and compulsive cravings.

GHB addiction occurs when repeated drug use disrupts the normal balance of brain circuits that control rewards, memory and cognition, ultimately leading to compulsive drug taking.[31][32] Although there have been reported fatalities due to GHB withdrawal, reports are inconclusive and further research is needed.[33]

Ketamine risks

Ketamine use as a recreational drug has been implicated in deaths globally, with more than 90 deaths in England and Wales in the years of 2005–2013.[34] They include accidental poisonings, drownings, traffic accidents, and suicides.[34] The majority of deaths were among young people.[35] This has led to increased regulation (e.g., upgrading ketamine from a Class C to a Class B banned substance in the U.K.).[36] At sufficiently high doses, Ketamine users may experience what is called the "K-hole", a state of extreme dissociation with visual and auditory hallucinations.[37]

Acute treatment

The main treatment for individuals facing acute medical issues due to club drug consumption or overdoses is "cardiorespiratory maintenance".[25] Since club drug users may have consumed multiple drugs, a mix of alcohol and other drugs, or a drug adulterated with other chemicals, it is hard for doctors to know what type of overdose to treat for, even if the user is conscious and can tell the medical team what drug they think they took. A doctor recommends "cardiac monitoring, pulse oximetry, urinalysis, and performance of a comprehensive chemistry panel to check for electrolyte imbalance, renal toxicity, and possible underlying disorders" and preventing "seizures".[25] Some doctors use activated charcoal and a cathartic" to detoxify the drugs in the gastrointestinal system.[25] Cooling the victim is recommended to avoid hyperthermia. If the victim overdosed on Rohypnol, the antidote flumazenil can be given; this is the only club drug for which there is an antidote.[25]

History

In the mid to late-1970s disco club scene, there was a thriving drug subculture, particularly for drugs that would enhance the experience of dancing to the loud dance music and the flashing lights on the dancefloor. Substances such as cocaine[38] (nicknamed "blow"), amyl nitrite ("poppers"),[39] and Quaaludes. Quaaludes were described as [the] "...other quintessential 1970s club drug", which suspends motor coordination."[40]) According to Peter Braunstein, "massive quantities of drugs were ingested in discothèques."

Throughout the 1980s, the use of club drugs expanded into colleges, social parties, and raves. As raves grew in popularity through the late 1980s and into the late 1990s, drug usage, especially MDMA, grew with them. Much like discos, raves made use of flashing lights, loud techno/electronic dance music to enhance the user experience. Before their scheduling, some club drugs (especially designer drugs referred to as research chemicals) were advertised as alcohol-free and drug-free. Another reason that drug producers create new drugs is to avoid drug laws.

Since the early 2000s, medical professionals have acknowledged and addressed the problem of the increasing consumption of alcoholic drinks and club drugs (such as MDMA, cocaine, rohypnol, GHB, ketamine, PCP, LSD, and methamphetamine) associated with rave culture among adolescents and young adults in the Western world.[41][42][43][44][45] Studies have shown that adolescents are more likely than young adults to use multiple drugs,[46] and the consumption of club drugs is highly associated with the presence of criminal behaviors and recent alcohol abuse or dependence.[47]

In Australia

Club drugs are used in Australia in a variety of dance clubs and nightclubs.[44] One in ten Australians have used MDMA at least once in their lifetime; one in thirty have used MDMA in the past 12 months. One in a hundred Australians has used ketamine at least once in their lives and one in five hundred over the past 12 months. One in two hundred Australians have used GHB at least once in their lives and one in one thousand in the past 12 months. Regarding the entire Australian population, seven per cent of Australians have used cocaine at least once in their lifetime and two per cent of Australians have used it in the past 12 months.[48] Today, these drugs are widely used across age and socioeconomic groups and often sold in nightclubs and pubs throughout Australia.

See also

- Party pills

- Route 36, world's first cocaine bar

- Chemsex, the use of drugs to enhance sex

References

- ↑ Bowden-Jones, Owen; Abdulrahim, Dima (2020). "Part I - Introduction: What Are Club Drugs and NPS and Why Are They Important?". Club Drugs and Novel Psychoactive Substances: The Clinician's Handbook. Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, and New Delhi: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–22. doi:10.1017/9781911623106. ISBN 978-1-911-62309-0. LCCN 2020026282.

- 1 2 "Club Drugs". www.drugabuse.gov. North Bethesda, Maryland: National Institute on Drug Abuse. 2021. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ↑

- Erowid reference 6889 Archived 2008-03-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Club Drugs: MedlinePlus". medlineplus.gov. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ↑ "What Are Club Drugs? Effects, Types, List of Street Names". emedicinehealth.com. Archived from the original on 16 September 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-06-08. Retrieved 2008-06-23.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - 1 2 3 4 "Club Drugs and Their Effects". Narconon International. Archived from the original on 31 January 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ↑ Tilstone, W.J.; Savage, K.A.; Clark, L.A. (2006). Forensic Science: An Encyclopedia of History, Methods, and Techniques. ABC-CLIO. p. 131. ISBN 978-1-57607-194-6. Archived from the original on 7 August 2018. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- ↑ Carvalho M, Carmo H, Costa VM, Capela JP, Pontes H, Remião F, Carvalho F, Bastos Mde L (August 2012). "Toxicity of amphetamines: an update". Arch. Toxicol. 86 (8): 1167–1231. doi:10.1007/s00204-012-0815-5. PMID 22392347. S2CID 2873101.

- ↑ Reynolds, Simon (1999). Generation Ecstasy: Into the World of Techno and Rave Culture. Routledge. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-415-92373-6.

- ↑ Epstein, edited by Barbara S. McCrady, Elizabeth E. (2013). Addictions : a comprehensive guidebook (Second ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 299. ISBN 978-0-19-975366-6.

{{cite book}}:|first1=has generic name (help) - ↑ "Director's Report to the National Advisory Council on Drug Abuse". National Institute on Drug Abuse. May 2000. Archived from the original on 3 February 2016.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2004). Neuroscience of psychoactive substance use and dependence. p. 89. ISBN 9789241562355.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2007). International medical guide for ships. p. 242. ISBN 9789241547208.

- ↑ Lawrence Young (31 January 2010). "METHAQUALONE". Drug Text. International Substance Use Library. Archived from the original on 23 April 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ↑ "Mandrax". DrugAware. Reality Media. 2003. Archived from the original on 2010-01-10. Retrieved 2009-08-13.

- 1 2 McCarthy, G; Myers, B; Siegfried, N (2005). "Treatment for methaqualone dependence in adults". Reviews (2): CD004146. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004146.pub2. PMID 15846700.

- ↑ "Mandrax Information" (PDF). Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- ↑ Vermeeren A. (2004). "Residual effects of hypnotics: epidemiology and clinical implications". CNS Drugs. 18 (5): 297–328. doi:10.2165/00023210-200418050-00003. PMID 15089115. S2CID 25592318.

- ↑ Mets, MA.; Volkerts, ER.; Olivier, B.; Verster, JC. (February 2010). "Effect of hypnotic drugs on body balance and standing steadiness". Sleep Medicine Reviews. 14 (4): 259–67. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2009.10.008. PMID 20171127.

- ↑ Aghajanian, G (1999). "Serotonin and Hallucinogens". Neuropsychopharmacology Reviews. 21 (2): 16S–23S. doi:10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00135-3. PMID 10432484.

- ↑ Psychedelic drugs induce 'heightened state of consciousness', brain scans show Archived 2017-04-24 at the Wayback Machine, guardian.com. Retrieved: 23 April 2017.

- ↑ Giannini, A. J. (1991). "Volatiles". In Miller, N. S. (ed.). Comprehensive Handbook of Drug and Alcohol Addiction. New York City: Marcel Dekker. p. 396. ISBN 978-0-8247-8474-4. S2CID 142846805.

- ↑

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Gahlinger, Paul. "Club Drugs: MDMA, Gamma-Hydroxybutyrate (GHB), Rohypnol, and Ketamine". In Am Fam Physician. 2004 Jun 1;69(11):2619-2627.

- ↑ "Club Drugs and Their Effects". thebody.com. Archived from the original on 22 March 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ↑ VV Pillay (2013), Modern Medical Toxicology (4th ed.), Jaypee, pp. 553–554, ISBN 978-93-5025-965-8

- ↑ Hiroyuki Inoue et al. (2008). "Characterization and Profiling of Methamphetamine Seizures" (PDF). Journal of Health Science. 54 (6): 615–622. doi:10.1248/jhs.54.615. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-06-24. Retrieved 2013-12-31.

- ↑ Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 15: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders". In Sydor A, Brown RY (ed.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 368. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

Such agents also have important therapeutic uses; cocaine, for example, is used as a local anesthetic (Chapter 2), and amphetamines and methylphenidate are used in low doses to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and in higher doses to treat narcolepsy (Chapter 12). Despite their clinical uses, these drugs are strongly reinforcing, and their long-term use at high doses is linked with potential addiction, especially when they are rapidly administered or when high-potency forms are given.

- ↑ "Cocaine: How It Works, Effects, and Risks". webmd.com. Archived from the original on 27 February 2014. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ↑ Department of Health and Human Services, SAMHSA Office of Applied Studies 2005 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (ages 12 years and up); American Heart Association; Johns Hopkins University study, Principles of Addiction Medicine; Psychology Today; National Gambling Impact Commission Study; National Council on Problem Gambling; Illinois Institute for Addiction Recovery; Society for Advancement of Sexual Health; All Psych Journal

- ↑ Addiction and the Brain Archived 2010-07-24 at the Wayback Machine. Time

- ↑ Galloway GP, Frederick SL, Staggers FE, Gonzales M, Stalcup SA, Smith DE (1997). "Gamma-hydroxybutyrate: an emerging drug of abuse that causes physical dependence". Addiction. 92 (1): 89–96. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1997.tb03640.x. PMID 9060200.

- 1 2 See Max Daly, 2014, "The Sad Demise of Nancy Lee, One of Britain's Ketamine Casualties," at Vice (online), July 23, 2014, see Archived 2015-06-07 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 7 June 2015.

- ↑ The Crown, 2013, "Drug related deaths involving ketamine in England and Wales," a report of the Mortality team, Life Events and Population Sources Division, Office for National Statistics, the Crown (U.K.), see Archived 2015-06-07 at the Wayback Machine and Archived 2015-06-19 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 7 June 2015.

- ↑ Hayley Dixon, 2014, "Ketamine death of public schoolgirl an 'act of stupidity which destroyed family'," at The Telegraph (online), February 12, 2014, see Archived 2017-08-24 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 7 June 2015.

- ↑ Giannini, AJ (1999). Drug Abuse. Los Angeles: Health Information Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-885987-11-2.

- ↑ Gootenberg, Paul (1954). Between Coca and Cocaine: A Century or More of, pp. 119–150. He says that, "The relationship of cocaine to 1970s disco culture cannot be stressed enough; ...".

- ↑ Amyl, butyl and isobutyl nitrite (collectively known as alkyl nitrites) are clear, yellow liquids which are inhaled for their intoxicating effects. Nitrites originally came as small glass capsules that were popped open. This led to nitrites being given the name 'poppers' but this form of the drug is rarely found in the UK The drug became popular in the UK first on the disco/club scene of the 1970s and then at dance and rave venues in the 1980s and 1990s. Available at: "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-04-05. Retrieved 2007-04-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-02-05. Retrieved 2010-02-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) – 76k - - ↑ Weir, Erica (June 2000). "Raves: a review of the culture, the drugs and the prevention of harm" (PDF). CMAJ. Canadian Medical Association. 162 (13): 1843–1848. eISSN 1488-2329. ISSN 0820-3946. LCCN 87039047. PMC 1231377. PMID 10906922. S2CID 10853457. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 June 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ↑ Larive, Lisa L.; Romanelli, Frank; Smith, Kelly M. (June 2002). "Club drugs: methylenedioxymethamphetamine, flunitrazepam, ketamine hydrochloride, and gamma-hydroxybutyrate". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. 59 (11): 1067–1076. doi:10.1093/ajhp/59.11.1067. eISSN 1535-2900. ISSN 1079-2082. OCLC 41233599. PMID 12063892. S2CID 44680086.

- ↑ Klein, Mary; Kramer, Frances (February 2004). "Rave drugs: pharmacological considerations" (PDF). AANA Journal. American Association of Nurse Anesthetists. 72 (1): 61–67. ISSN 0094-6354. PMID 15098519. S2CID 41926572. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 August 2021. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- 1 2 Degenhardt, Louisa; Copeland, Jan; Dillon, Paul (2005). "Recent trends in the use of "club drugs": an Australian review". Substance Use & Misuse. Taylor & Francis. 40 (9–10): 1241–1256. doi:10.1081/JA-200066777. eISSN 1532-2491. ISSN 1082-6084. LCCN 2006268261. PMID 16048815. S2CID 25509945.

- ↑ Avrahami, Beni; Bentur, Yedidia; Halpern, Pinchas; Moskovich, Jenny; Peleg, Kobi; Soffer, Dror (April 2011). "Morbidity associated with MDMA (ecstasy) abuse: a survey of emergency department admissions". Human & Experimental Toxicology. SAGE Publications. 30 (4): 259–266. doi:10.1177/0960327110370984. eISSN 1477-0903. ISSN 0960-3271. LCCN 90031138. PMID 20488845. S2CID 30994214.

- ↑ Palamar JJ, Acosta P, Le A, Cleland CM, Nelson LS (November 2019). "Adverse drug-related effects among electronic dance music party attendees". International Journal of Drug Policy. Elsevier. 73: 81–87. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.07.005. ISSN 1873-4758. PMC 6899195. PMID 31349134. S2CID 198932918.

- ↑ Wu, Li-Tzy; Schlenger, William E.; Galvin, Deborah M. (September 2006). "Concurrent Use of Methamphetamine, MDMA, LSD, Ketamine, GHB, and Flunitrazepam among American Youths". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. Elsevier. 84 (1): 102–113. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.01.002. ISSN 0376-8716. PMC 1609189. PMID 16483730. S2CID 24699584.

- ↑ Australia Defence Force (ADF), n.d).

Further reading

- Hunt, Geoffrey; Moloney, Molly; and Evans, Kristin. Youth, Drugs, and Nightlife. Routledge, 2010.

- Knowles, Cynthia R. Up all night: a closer look at club drugs and rave culture. Red House Press, 2001.

- Sanders, Bill. Drugs, Clubs and Young People: Sociological and Public Health Perspectives. Routledge, 2016.