Driving under the influence

Driving under the influence (DUI or DWI) is the offense of driving, operating, or being in control of a vehicle while impaired by alcohol or drugs (including recreational drugs and those prescribed by physicians), to a level that renders the driver incapable of operating a motor vehicle safely.[1] Multiple other terms are used for the offense in various jurisdictions.

Terminology

The name of the offense varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction and from legal to colloquial terminology. In various jurisdictions the offense is termed driving while impaired, impaired driving, driving while intoxicated (DWI), drunk driving, operating while intoxicated (OWI), operating under the influence (OUI), operating [a] vehicle under the influence (OVI), and drink-driving (UK/Ireland).

In the United States, the specific criminal offense is usually called driving under the influence, but states may use other names for the offense including "driving while intoxicated" (DWI), "operating while impaired" (OWI) or "operating while ability impaired", and "operating a vehicle under the influence" (OVI).[2] Such laws may also apply to boating or piloting aircraft. Vehicles can include farm machinery and horse-drawn carriages, along with bicycles. Other commonly used terms to describe these offenses include drinking and driving, drunk driving, drunken driving, impaired driving, operating under the influence, or "over the prescribed limit".

In the United Kingdom, there are two separate offences to do with alcohol and driving. The first is "Driving or attempting to drive with excess alcohol" (legal code DR10), the other is known as "In charge of a vehicle with excess alcohol" (legal code DR40) or "drunk in charge" due to the wording of the Licensing Act 1872.[3][4] In relation to motor vehicles, the Road Safety Act 1967 created a narrower offense of driving (or being in charge of) a vehicle while having breath, blood, or urine alcohol levels above the prescribed limits (colloquially called "being over the limit"); and a broader offense of "driving while unfit through drink or drugs," (DR20 and DR80 respectively) which can apply even with levels below the limits.[5] These provisions were re-enacted in the Road Traffic Act 1988. A separate offense in the 1988 Act applies to bicycles. While the 1872 Act is mostly superseded, the offense of being "drunk while in charge ... of any carriage, horse, cattle, or steam engine" is still in force; "carriage" has sometimes been interpreted as including mobility scooters.[4]

Definition

The criminal offense may not involve actual driving of the vehicle, but rather may broadly include being physically "in control" of a car while intoxicated, even if the person charged is not in the act of driving.[6][7] For example, individuals found in the driver's seat of a car while intoxicated and holding the car keys, even while parked, may be charged with DUI in the majority of U.S. states because they are in control of the vehicle.

In construing the terms DUI, DWI, OWI, and OVI, a few states[which?] such as California therefore make it illegal to drive a motor vehicle while under the influence or driving while intoxicated while the others all indicate that it is illegal to operate a motor vehicle while under the influence. Virtually all of the states permit enforcement of DUI/DWI and OWI/OVI statutes based on "operation and control" of a vehicle, while California and a few others[which?] require actual "driving". "The distinction between these two terms is material, for it is generally held that the word 'drive,' as used in statutes of this kind, usually denotes movement of the vehicle in some direction, whereas the word 'operate' has a broader meaning so as to include not only the motion of the vehicle but also acts which engage the machinery of the vehicle that, alone or in sequence, will set in motion the motive power of the vehicle." (State v. Graves (1977) 269 S.C. 356 [237 S.E.2d 584, 586–588, 586. fn. 8].)

Merriam Webster's Dictionary defines DUI (in the United States) as "1. the act or crime of driving a vehicle while affected by alcohol or drugs; 2. an arrest or conviction for driving under the influence; 3. a person who is arrested for or convicted of driving under the influence."[8]

In some countries (including Australia and many jurisdictions throughout the United States), a person can be charged with a criminal offense for riding a bicycle, skateboard, or horse while intoxicated or under the influence of alcohol.[9][10][11]

Alcohol

With alcohol consumption, a drunk driver's level of intoxication is typically determined by a measurement of blood alcohol content or BAC; but this can also be expressed as a breath test measurement, often referred to as a BrAC. A BAC or BrAC measurement in excess of the specific threshold level, such as 0.08%, defines the criminal offense with no need to prove impairment.[12] In some jurisdictions, there is an aggravated category of the offense at a higher BAC level, such as 0.12%, 0.15%, or 0.25%. In many jurisdictions, police officers can conduct field tests of suspects to look for signs of intoxication. The legal limit in Florida is .08% BAC.[13] The US state of Colorado has a maximum blood content of THC for drivers who have consumed cannabis, but it has been difficult to enforce.[14]

In some countries, it is measured and known in gram per blood liter, with 0.5 g/L similar to a 0.05% rate, other use per mille (per thousand sign) with 0.5‰ = 0.05%.

Blood alcohol content

Drinking enough alcohol to cause a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) of 0.03–0.12% typically causes a flushed, red appearance in the face and impaired judgment and fine muscle coordination. A BAC of 0.09% to 0.25% causes lethargy, sedation, balance problems, and blurred vision. A BAC from 0.18% to 0.30% causes profound confusion, impaired speech (e.g., slurred speech), staggering, dizziness, and vomiting. A BAC from 0.25% to 0.40% causes stupor, unconsciousness, anterograde amnesia, vomiting, and respiratory depression (potentially life-threatening). A BAC from 0.35% to 0.80% causes a coma (unconsciousness), life-threatening respiratory depression, and possibly fatal alcohol poisoning. There are a number of factors that affect the time in which BAC will reach or exceed 0.08, including weight, the time since one's recent drinking, and whether and what one ate within the time of drinking. A 170 lb male can drink more than a 135 lb female, before being over the BAC level.[15]

NHTSA reports that the following blood alcohol levels (BAC) in a driver will have the following predictable effects on his or her ability to drive safely: (1) A BAC of .02 will result in a "[d]ecline in visual functions (rapid tracking of a moving target), decline in ability to perform two tasks at the same time (divided attention)"; (2) A BAC of .05 will result in "[r]educed coordination, reduced ability to track moving objects, difficulty steering, reduced response to emergency driving situations"; (3) A BAC of .08 will result in "[c]oncentration, short-term memory loss, speed control, reduced information processing capability (e.g., signal detection, visual search), impaired perception"; (4) A BAC of .10 will result in "[r]educed ability to maintain lane position and brake appropriately"; and (5) A BAC of .15 will result in "[s]ubstantial impairment in vehicle control, attention to driving task, and in necessary visual and auditory information processing."[16]

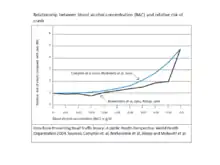

A breathalyzer is a device for estimating BAC from a breath sample. It was developed by inventor Robert Frank Borkenstein[17] and registered as a trademark in 1954, but many people use the term to refer to any generic device for estimating blood alcohol content.[18] With the advent of a scientific test for BAC, law enforcement regimes moved from sobriety tests (e.g., asking the suspect to stand on one leg) to having more than a prescribed amount of blood alcohol content while driving. However, this does not preclude the simultaneous existence and use of the older subjective tests in which police officers measure the intoxication of the suspect by asking them to do certain activities or by examining their eyes and responses. BAC is most conveniently measured as a simple percent of alcohol in the blood by weight.[19] Research shows an exponential increase of the relative risk for a crash with a linear increase of BAC as shown in the illustration.(Relative risk of a crash based on blood alcohol levels) BAC does not depend on any units of measurement. In Europe, it is usually expressed as milligrams of alcohol per 100 milliliters of blood. However, 100 milliliters of blood weighs essentially the same as 100 milliliters of water, which weighs precisely 100 grams. Thus, for all practical purposes, this is the same as the simple dimensionless BAC measured as a percent. The per mille (promille) measurement, which is equal to ten times the percentage value, is used in Denmark, Germany, Finland, Norway, and Sweden.[20]

Depending on the jurisdiction, BAC may be measured by police using three methods: blood, breath, or urine. For law enforcement purposes, breath is the preferred method, since results are available almost instantaneously. The validity of the testing equipment/methods and mathematical relationships for the measurement of breath and blood alcohol have been criticized.[21] Improper testing and equipment calibration is often used in defense of a DUI or DWI. There have been cases in Canada where officers have come upon a suspect who is unconscious after a crash and officers have taken a blood sample.

Driving while consuming alcohol may be illegal within a jurisdiction. In some, it is illegal for an open container of an alcoholic beverage to be in the passenger compartment of a motor vehicle or in some specific area of that compartment. There have been cases of drivers being convicted of a DUI when they were not observed driving after being proven in court they had been driving while under the influence.[6][7]

In the case of a crash, car insurance may be automatically declared invalid for the intoxicated driver; the drunk driver would be fully responsible for damages. In the American system, a citation for driving under the influence also causes a major increase in car insurance premiums.[22]

The German model serves to reduce the number of crashes by identifying unfit drivers and revoking their licenses until their fitness to drive has been established again. The medical-psychological assessment works for a prognosis of the fitness for drive in future, has an interdisciplinary basic approach, and offers the chance of individual rehabilitation to the offender.[23]

George Smith, a London Taxi cab driver, ended up being the first person to be convicted of driving a motor vehicle while intoxicated, on September 10, 1897, under the "drunk in charge" provision of the 1872 Licensing Act. He was fined 25 shillings.

Risks

Driving under the influence is one of the largest risk factors that contribute to traffic collisions. For people in Europe between the age of 15 and 29, driving under the influence is one of the main causes of mortality.[25] According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, alcohol-related crashes cause approximately $37 billion in damages annually.[26] DUI and alcohol-related crashes produce an estimated $45 billion in damages every year. The combined costs of towing/storage fees, attorney fees, bail fees, fines, court fees, ignition interlock devices, traffic school fees and DMV fees mean that a first-time DUI charge could cost thousands to tens of thousands of dollars.[27]

Studies show that a high BAC increases the risk of collisions whereas it is not clear if a BAC of 0.01–0.05% slightly increases or decreases the risk.[28][29]

Traffic collisions are predominantly caused by driving under the influence for people in Europe between the age of 15 and 29, it is one of the main causes of mortality.[25] According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, alcohol-related collisions cause approximately $37 billion in damages annually.[26] Every 51 minutes someone dies from an alcohol-related collision. When it comes to risk-taking there is a larger male to female ratio as personality traits, antisociality, and risk-taking are taken into consideration as they all are involved in DUI's.[30] Over 7.7 million underage people ages 12–20 claim to drink alcohol, and on average, for every 100,000 underage Americans, 1.2 died in drunk-driving traffic crashes.[31]

In the U.S., Southern and Northern Central states have the highest prevalence of fatalities due to DUI collisions. A 2019 study that weighed arrest and census figures with National Highway Traffic Safety Administration stats on fatal crashes found that seven of the 12 states with the highest DUI death rates are Southern, led by the Carolinas, Mississippi, Alabama, Texas, Louisiana, and Arkansas. But the most DUI fatalities per capita are found in the North-Central region, where Wyoming, Montana, and the Dakotas top the overall ranking as the states with the most acute DUI crises.[32]

Grand Rapids Dip

Some studies suggest that a BAC of 0.01–0.04% would have a lower risk of collisions compared to a BAC of 0%, referred to as the Grand Rapids Effect or Grand Rapids Dip,[29][33] based on a seminal research study by Borkenstein, et al.[34] (Robert Frank Borkenstein is well known for inventing the Drunkometer in 1938, and the Breathalyzer in 1954.)[35] One study suggests that a BAC of 0.04–0.05% would slightly increase the risk.[29]

Some literature has attributed the Grand Rapids Effect to erroneous data or asserted (without support) that it was possibly due to drivers exerting extra caution at low BAC levels or to "experience" in drinking. Other explanations are that this effect is at least in part the blocking effect of ethanol excitotoxicity and the effect of alcohol in essential tremor and other movement disorders,[36] but this remains speculative.

Both the influential study by Borkenstein, et al. and the empirical German data on the 1990s demonstrated that the risk of collisions is lower or the same for drivers with a BAC of 0.04% or less than for drivers with a BAC of 0%. For a BAC of 0.15%, the risk is 25-fold. The 0.05% BAC limit in Germany (since 1998, 0.08% since 1973) and the limits in many other countries were set based on the study by Borkenstein, et al. Würzburg University researchers showed that all extra collisions caused by alcohol were due to at least 0.06% BAC, 96% of them due to BAC above 0.08%, and 79% due to BAC above 0.12%.[29] In their study based on the 1990s German data, the effect of alcohol was higher for almost all BAC levels than in Borkenstein, et al.

Other drugs

For drivers suspected of drug-impaired driving, drug testing screens are typically performed in scientific laboratories so that the results will be admissible in evidence at trial. Due to the overwhelming number of impairing substances that are not alcohol, drugs are classified into different categories for detection purposes. Drug impaired drivers still show impairment during the battery of standardized field sobriety tests, but there are additional tests to help detect drug impaired driving.

The Drug Evaluation and Classification program is designed to detect a drug impaired driver and classify the categories of drugs present in his or her system. Initially developed by the Los Angeles, California, Police Department in the 1970s, the DEC program breaks down detection into a twelve-step process that a government-certified Drug Recognition Expert (DRE) can use to determine the category or categories of drugs that a suspect is impaired by. The twelve steps are:

- Breath Alcohol Test

- Interview with arresting officer (who notes slurred speech, alcohol on breath, etc.)

- Preliminary evaluation

- Evaluation of the eyes

- Psychomotor tests

- Vital signs

- Dark room examinations

- Muscle tone

- Injection sites (for injection of heroin or other drugs)

- Interrogation of suspect

- Opinion of the evaluator

- Toxicological examination[37]

DREs are qualified to offer expert testimony in court that pertains to impaired driving on drugs.

The DEC program is recognized by all fifty states in the U.S., Canada, and the United Kingdom and DRE training in the use of the twelve-step [MS1] process is scientifically validated by both laboratory and field studies.[38]

Recreational drugs

Drivers who have smoked or otherwise consumed cannabis products such as marijuana or hashish can be charged and convicted of impaired driving in some jurisdictions. A 2011 study in the B.C. Medical Journal stated that there "...is clear evidence that cannabis, like alcohol, impairs the psychomotor skills required for safe driving." The study stated that while "[c]annabis-impaired drivers tend to drive more slowly and cautiously than drunk drivers,... evidence shows they are also more likely to cause accidents than drug and alcohol-free drivers".[39] In Canada, police forces such as the Royal Canadian Mounted Police have "...specially trained drug recognition and evaluation [DRE] officers... [who] can detect whether or not a driver is drug impaired, by putting suspects through physical examinations and co-ordination tests.[39] In 2014, in the Canadian province of Ontario, Bill 31, the Transportation Statute Law Amendment Act, was introduced to the provincial legislature. Bill 31 contains driver's license "...suspensions for those caught driving under the influence of drugs, or a combination of drugs and alcohol.[40] Ontario police officers "...use Standard Field Sobriety Tests (SFSTs) and drug recognition evaluations to determine whether the officer believes the driver is under the influence of drugs."[40] In the province of Manitoba, an "...officer can issue a physical coordination test. In B.C., the officer can further order a drug recognition evaluation by an expert, which can be used as evidence of drug use to pursue further charges."[40]

In the US state of Colorado, the state government indicates that "[a]ny amount of marijuana consumption puts you at risk of driving impaired."[41] Colorado law states that "drivers with five nanograms of active tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) in their whole blood can be prosecuted for driving under the influence (DUI). However, no matter the level of THC, law enforcement officers base arrests on observed impairment."[41] In Colorado, if consumption of marijuana is impairing your ability to drive, "it is illegal for you to be driving, even if that substance is prescribed [by a doctor] or legally acquired."[41]

Prescription medications

Prescription medications such as opioids and benzodiazepines often cause side effects such as excessive drowsiness, and, in the case of opioids, nausea.[42] Other prescription drugs including antiepileptics and antidepressants are now also believed to have the same effect.[43] In the last ten years, there has been an increase in motor vehicle crashes, and it is believed that the use of impairing prescription drugs has been a major factor.[43] Workers are expected to notify their employer when prescribed such drugs to minimize the risk of motor vehicle crashes while at work.

If a worker who drives has a health condition which can be treated with opioids, then that person's doctor should be told that driving is a part of the worker's duties and the employer should be told that the worker could be treated with opioids.[44] Workers should not use impairing substances while driving or operating heavy machinery like forklifts or cranes.[44] If the worker is to drive, then the health care provider should not give them opioids.[44] If the worker is to take opioids, then their employer should assign them work which is appropriate for their impaired state and not encourage them to use safety sensitive equipment.[45]

Field sobriety testing

To attempt to determine whether a suspect is impaired, police officers in the United States usually will administer field sobriety tests to determine whether the officer has probable cause to arrest an individual for suspicion of driving under the influence (DUI).

A police officer in the United States must have Probable Cause to make an arrest for driving under the influence. In establishing probable cause for a DUI arrest, officers frequently consider the suspect's performance of Standardized Field Sobriety Tests. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) developed a system for validating field sobriety tests that led to the creation of the Standardized Field Sobriety Test (SFST) battery of tests. The NHTSA established a standard battery of three roadside tests that are recommended to be administered in a standardized manner in making this arrest decision.[46] There are Non-Standardized Field Sobriety Tests as well; however, the Non-Standardized Field Sobriety Tests have not received NHTSA Validation. This is the difference between the "Standardized" and the "Non-Standardized" Field Sobriety Tests. The NHTSA has published numerous training manuals associated with SFSTs. As a result of the NHTSA studies, the Walk-and-Turn test was determined to be 68% accurate in predicting whether a test subject is at or above 0.08%, and the One-Leg Stand Test was determined to be 65% accurate in predicting whether a test subject is at or above 0.08% when the tests are properly administered to people within the study parameters.

The three validated tests by NHTSA are:

- The Horizontal Gaze Nystagmus Test, which involves following an object with the eyes (such as a pen or other stimulus) to determine characteristic eye movement reaction to the stimulus

- The Walk-and-Turn Test (heel-to-toe in a straight line). This test is designed to measure a person's ability to follow directions and remember a series of steps while dividing attention between physical and mental tasks.

- The One-Leg-Stand Test

Alternative tests, which have not been validated by the NHTSA, include the following:

- The Romberg Test, or the Modified-Position-of-Attention Test, (feet together, head back, eyes closed for thirty seconds).

- The Finger-to-Nose Test (tip head back, eyes closed, touch the tip of nose with tip of index finger).

- The Alphabet Test (recite all or part of the alphabet).

- The Finger Count Test (touch each finger of hand to thumb counting with each touch (1, 2, 3, 4, 4, 3, 2, 1)).

- The Counting Test (counting backwards from a number ending in a digit other than 5 or 0 and stopping at a number ending in a digit other than 5 or 0. The series of numbers should be more than 15).

- The Preliminary Alcohol Screening Test, PAS Test or PBT, (breathe into a "portable or preliminary breath tester", PAS Test or PBT).

In the US, field sobriety tests are voluntary; however, some states mandate commercial drivers accept preliminary breath tests (PBT).

Preliminary Breath Test (PBT) or Preliminary Alcohol Screening test (PAS)

The Preliminary Breath Test (PBT) or Preliminary Alcohol Screening test (PAS) is sometimes categorized as part of field sobriety testing, although it is not part of the series of performance tests. The PBT (or PAS) uses a portable breath tester. While the tester provides numerical blood alcohol content (BAC) readings, its primary use is for screening and establishing probable cause for arrest, to invoke the implied consent requirements. In US law, this is necessary to sustain a conviction based on evidential testing (or implied consent refusal).[47] Regardless of the terminology, in order to sustain a conviction based on evidential tests, probable cause must be shown (or the suspect must volunteer to take the evidential test without implied consent requirements being invoked).[47]

Refusal to take a preliminary breath test (PBT) in Michigan subjects a non-commercial driver to a "civil infraction" penalty, with no violation "points",[48] but is not considered to be a refusal under the general "implied consent" law.[49] In some states, the state may present evidence of refusal to take a field sobriety test in court, although this is of questionable probative value in a drunk driving prosecution.

Different requirements apply in many states to drivers under DUI probation, in which case participation in a preliminary breath test (PBT) may be a condition of probation. Some US states, notably California, have statutes on the books penalizing PBT refusal for drivers under 21; however, the Constitutionality of those statutes has not been tested. (As a practical matter, most criminal lawyers advise not engaging in discussion or "justifying" a refusal with the police.)

Commercial drivers are subject to PBT testing in some US states as a "drug screening" requirement.

Testing for cannabis

U.S. states prohibit the operation of a motor vehicle while under the influence of drugs, including marijuana.[50] For example, in Illinois it is illegal to operate a motor vehicle with a THC level of 5 nanograms or more per milliliter of whole blood or 10 nanograms or more per milliliter of other bodily substances.[51] Under that law, an individual can be arrested for driving under influence of cannabis at any THC level, including under the per se legal limits if an Officer believes the individual is impaired by cannabis.[51]

It can be important to perform testing soon after a traffic stop, as THC plasma levels decline significantly after the passage of one or two hours.[52] A number of companies are developing roadside THC breathalyzers that may be used by the police to help identify drivers impaired by the use of marijuana. Some nations use saliva swabs to test for THC levels at roadside, but questions remain about the reliability of saliva testing.[53]

Other charges

Child endangerment

In the US state of Colorado, impaired drivers may be charged with child endangerment if they are arrested for DUI with minor children in the vehicle.[54]

Wet reckless

"Wet reckless" is the informal term for a reckless driving charge that involves alcohol use by the driver. In California, a driver may not be charged or arrested for "wet reckless" driving, and the sole function of the charge is as a possible disposition following a plea bargain for a driver charged with DUI.[55]

Laws by country

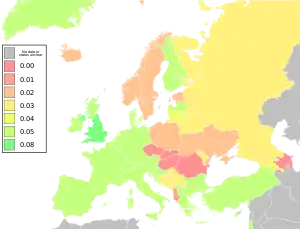

Map of Europe with BAC levels |

| Key: 0.05% = 0.5‰ = 0.5 gram/liter |

| Legend:

0.00%

0.01%

0.02%

0.03%

0.04%

0.05%

0.08%

No data |

|---|

| Additional country-specific limits are not taken into account: Some EU-member states have different penalties for different limits and have different limits for novice drivers and professional drivers. These limits are not mentioned.[56] |

The laws relating to drunk driving vary between countries or subnational regions (e.g., states or provinces), and varying blood alcohol content is required before a charge or conviction can be made.[57]

The specific criminal offense may be called, depending on the jurisdiction, "driving under the influence" [of alcohol or other drugs] (DUI), "driving under the influence of intoxicants" (DUII), "driving while impaired" (DWI), "operating vehicle under the influence of alcohol or other drugs" (OVI), "operating under the influence" (OUI), "operating while intoxicated" (OWI), "operating a motor vehicle while intoxicated" (OMVI), "driving under the combined influence of alcohol or other drugs", "driving under the influence per se" or "drunk in charge" [of a vehicle]. Many such laws apply also to motorcycling, boating, piloting aircraft, use of mobile farm equipment such as tractors and combines, riding horses or driving a horse-drawn vehicle, or bicycling, possibly with different BAC level than driving. In some jurisdictions, there are separate charges depending on the vehicle used. In Washington state, for instance, BUI (bicycling under the influence) laws recognize that intoxicated cyclists are likely to primarily endanger themselves. Accordingly, law enforcement officers are empowered only to protect the cyclist by impounding the bicycle rather than filing DUI charges.[58]

Some jurisdictions have multiple levels of BAC for different categories of drivers; for example, the state of California has a general 0.08% BAC limit, a lower limit of 0.04% for commercial operators, and a limit of 0.01% for drivers who are under 21 or on probation for previous DUI offenses.[59] In some jurisdictions, impaired drivers who injure or kill another person while driving may face heavier penalties.

Some jurisdictions, such as Massachusetts and Texas, have judicial guidelines requiring a mandatory minimum sentence for repeat offenders or for DUI/DWI offences with enhancements like an open container. The strictest states like Washington even have mandatory minimum penalties for first-time offenders[60]

DUI convictions may result in multi-year jail terms and other penalties ranging from fines and other financial penalties to forfeiture of one's license plates and vehicle. In many jurisdictions, a judge may also order the installation of an ignition interlock device. Some jurisdictions require that drivers convicted of DUI offenses use special license plates that are easily distinguishable from regular plates. These plates are known in popular parlance as "party plates"[61] or "whiskey plates".

In many countries, sobriety checkpoints (roadblocks of police cars where drivers are checked), driver's licence suspensions, fines, and prison sentences for DUI offenders are used as part of an effort to deter impaired driving. In addition, many countries have prevention campaigns that use advertising to make people aware of the danger of driving while impaired and the potential fines and criminal charges, discourage impaired driving, and encourage drivers to take taxis or public transport home after using alcohol or other drugs. In some jurisdictions, a bar or restaurant that serves an impaired driver may face civil liability for injuries caused by that driver. In some countries, non-profit advocacy organizations, a well-known example being Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) run their own publicity campaigns against drunk driving.

Argentina

In Argentina, it is a criminal offence to drive if one's level of alcohol is 0.03% or greater at local/municipal jurisdiction, stopped by a municipal police force and 0.04% if driving on a route or highway and stopped by a State Highway Patrol, Argentina Federal Police, or Argentina Gendarmerie. At the Cordoba State highways and routes, a zero-tolerance policy is enforced by Cordoba State Highway Patrol and it is an offence to drive with an alcohol level greater than 0.00%.

Australia

In Australia it is a criminal offence to drive under the influence of alcohol if one's level of alcohol is 0.05% or greater (full licence) or if one's level of alcohol is greater than 0.00% (learner/provisional).[62] Australian police utilise random breath testing stations, and any police vehicle can pull over any vehicle at any time to conduct a random breath or drug test. People found to have excessive alcohol or any banned substances are taken to either a police station or a random breath testing station for further analysis. Those over 0.08% will receive an automatic disqualification of their licence and must appear in court.[63]

Canada

In Canada, refusal to blow into a blood alcohol testing device provided by a police officer carries the same penalties as being found guilty of drunk driving.[64]

The Canadian criminal code was amended on December 18, 2018 to carry more severe immigration-related consequences for both permanent residents and foreign nationals convicted of an impaired driving offence. This has made impaired driving to be considered a serious criminal offence, making an increased maximum sentence from five to ten years.[65][66]

Commentary varies on taking Standardised Field Sobriety Tests (SFSTs) in Canada. Some sources, especially official ones, indicate that the SFSTs are mandatory,[67][68][69] whereas other sources are silent on FST testing.[70] The assertion regarding mandatory compliance with SFSTs is based on "failure to comply with a demand", as an offence under § 254(5) of the Criminal Code, but it is unclear how refusal of SFSTs are treated (provided the suspect agrees to take a chemical test). There are some reports that refusal to submit to an SFST can result in the same penalties as impaired driving.

Nevertheless, it is unclear whether there has ever been a prosecution under this interpretation of "failure to comply with a demand" as applied to SFSTs. Canada Criminal Code § 254(1) and (5) addresses this, but only with respect to chemical testing (breath, blood, etc.)[71]

Many provinces have administrative penalties related to drunk driving.[72] These penalties include immediate driver's licence suspensions and heavy fines. These penalties are often imposed for blood-alcohol concentrations exceeding 50 mg/dL,[73] rather than the Criminal Code of Canada prohibition of 80 mg/dL.[74]

Slovenia

The driver's license of those who reject the sobriety test may be revoked permanently, and their revocation stays in records indefinitely. At the European Court of Human Rights, there is currently a case pending which aims at the ruling that such sanction is excessive.[75]

South Korea

In Republic of Korea, it is a crime to drive if one's level of alcohol is 0.03% or greater.[76] Police often operate sobriety checkpoints without advance notice, and it is a criminal offense to refuse a sobriety test. Driving under the influence of alcohol results in suspension or disqualification of driver's license.

However, in the case of fatal accidents, it is often criticised that the sentence given by courts in South Korea is too low. This is because the sentencing standard for drunk driving fatal accidents in South Korea is up to 8-10 years in prison. In fact, most of them end up with about 3 years in prison, and even drunk driving repeat offenders are often sentenced to 3 years in prison, the minimum sentence.[77]

United Kingdom

In United Kingdom law it is a criminal offence to be drunk in charge of a motor vehicle. The determination of being "in charge" depends on such things as being in or near the vehicle, and having access to a means of starting the vehicle's engine and driving it away (e.g. the keys to the vehicle).

In the UK, drunk driving requires an objective measurement of fitness (or otherwise) to drive, however there is also a "prescribed limit" offence of driving a motor vehicle with excess alcohol in the body above the prescribed limit. There are different prescribed limits in different jurisdictions within the United Kingdom. In England and Wales, and in Northern Ireland, the prescribed limit is 35 micrograms of alcohol per 100 millilitres of expired alveolar breath (or 80 milligrams of alcohol per 100 millilitres of blood): in Scotland, however, the prescribed limit is only just over half of this, i.e. 22 micrograms of alcohol per 100 millilitres of expired alveolar breath (or 50 milligrams of alcohol per 100 millilitres of blood). The request to take a screening breath test must be made by a police officer in uniform, but can only be made if one of the following situations apply:

- the police officer has reasonable cause to suspect that the driver has committed, or is committing, a moving traffic offence, or

- if, having stopped, an officer has reasonable cause to suspect that the person driving/attempting to drive/in charge of the vehicle has consumed alcohol, or

- the police officer has reasonable cause to believe that the person is or was driving/attempting to drive/in charge of a motor vehicle when it was involved in an accident.[78]

A person must be disqualified from driving post-conviction for drink driving for a minimum of 12 months, and will usually receive a fine or imprisonment.[79]

The UK's drug driving laws were amended in 2015. The changes included a new roadside testing kit, which could detect the presence of cocaine and cannabis in a suspect's saliva and zero tolerance limits for a number of illegal drugs. Limits were also set for certain prescription medications. The laws, however, did not end the use of the field impairment test, but made them more relevant for determining driver impairment by those drugs that are not now covered by the new legislation, or cannot be identified by the limited use of a device, that currently are only authorised for cannabis and cocaine.[80][81]

United States

Under the laws of the United States, it is unlawful to drive a motor vehicle when the ability to do so is materially impaired by the consumption of alcohol or other drugs, including prescription medications.[82] For impaired driving charges involving the consumption of alcohol, the blood alcohol level at which impairment is presumed is 0.08, although it is possible to be convicted of impaired driving with a lower blood alcohol level.

For example, the state of California has two basic drunk driving laws with nearly identical criminal penalties:[83]

- V.C. Sec. 23152(a) – it is a misdemeanor to drive under the influence of alcohol or other drugs.

- V.C. Sec. 23152(b) – it is a misdemeanor to drive with .08% or more of alcohol in one's blood.

Under the first law, a driver may be convicted of impaired driving based upon their inability to safely operate a motor vehicle, no matter what their blood alcohol level. Under the second law, it is per se unlawful to drive with a blood alcohol level of .08 or greater.

For commercial drivers, a BAC of 0.04 can result in a DUI or DWI charge. In most states, individuals under 21 years of age are subject to a zero-tolerance limit and even a small amount of alcohol can lead to a DUI arrest.

In some states, an intoxicated person may be convicted of a DUI in a parked car if the individual is sitting behind the wheel of the car.[84] In some jurisdictions, the occupant of a vehicle might be charged with impaired driving even if sleeping in the back seat based on proof of risk that the occupant would put the vehicle in motion while intoxicated.[85] Some states allow for a charge of attempted DUI if an officer can reasonably infer that the defendant intended to drive a vehicle while impaired.[86]

Repeated impaired driving offenses or an impaired driving incident that results in bodily injury to another may trigger more significant penalties, and potentially trigger a felony charge.[87]

Many states in the US have adopted truth in sentencing laws that enforce strict guidelines on sentencing, differing from previous practice where prison time was reduced or suspended after sentencing had been issued.[88]

Some states allow for conviction for impaired driving based upon a measurement of THC, through blood test or urine testing. For example, in Colorado and Washington, driving with a blood level of THC in excess of 5 nanograms can result in a DUI conviction. In Nevada, the legal THC limit is 2 nanograms. It is also possible for a driver to be convicted of impaired driving based upon the officer's observations of impairment, even if the driver is under the legal limit. In states that have not yet established a THC blood level that triggers a presumption of impaired driving, a driver may similarly be convicted of impaired driving based upon the officer's observations and performance on other sobriety tests.[89][90]

Prevalence

In the United States, local law enforcement agencies made 1,467,300 arrests nationwide for driving under the influence of alcohol in 1996, compared to 1.9 million such arrests during the peak year in 1983.[91] In 1997 an estimated 513,200 DWI offenders were in prison or jail, down from 593,000 in 1990 and up from 270,100 in 1986.[92] In the United States, DUI and alcohol-related collisions produce an estimated $45 billion in damages every year.[93] In some US and German studies BAC level 0.01–0.03% predicted a lower collision risk than BAC 0%,[94][95] possibly due to extra caution,[95] whereas BACs 0.08% or higher seem to be responsible for almost all extra crashes caused by alcohol.[29] For a BAC of 0.15% the risk is 25-fold.[94]

Implied consent

All U.S. states recognize "implied consent", pursuant to which drivers are deemed to have consented to being tested for intoxication as a condition of their operating motor vehicles on public roadways.[96] Implied consent laws may result in punishment for those who refuse to cooperate with blood alcohol testing after an arrest for suspected impaired driving, including civil consequences such as a driver's license suspension. The State of Kansas found unconstitutional a state law that made it an additional crime to refuse such a test when no court-ordered warrant for testing exists.[97] Under the implied consent law of the State of Michigan, a person who is arrested for drunk driving is required to take a chemical test to determine their blood alcohol content, and refusal will result in six points being added to their driver's license and their driving privileges will be suspended for one year.[98]

Federal regulation

The United States Department of Transportation (USDOT) regulates many occupations and industries, and has a zero tolerance policy pertaining to the use of cannabis for any regulated employee whether he or she is on-duty or off-duty. Regardless of any State's DUI Statutes and DMV Administrative Penalties, a Commercial Driver's License "CDL" holder will have his or her CDL suspended for 1-year for a DUI arrest and will have his or her CDL revoked for life if they are subsequently arrested for driving impaired.[51]

The United States Federal Railroad Administration and Federal Aviation Administration, both of which are part of the USDOT, respectively impose a 0.04% BAC limit for train crew and aircrew.[99]

Private employers

Some U.S. employers impose their own rules for drug and alcohol use by employees who operate motor vehicles. For example, the Union Pacific Railroad imposes a BAC limit of 0.02%,[100] that if, after an on-duty traffic crash, the determination that an employee violated that rule may result in termination of employment with no chance of future rehire.

See also

- Alcoholism

- Breathalyzer

- Designated driver

- DR10, UK police code

- Driving laws

- Drug–impaired driving

- Drunk drivers

- Drunk walking

- DUI laws in California

- DWI court

- Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder

- Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD)

- National Motorists Association

- Responsible drug use

- Driver's license: point system

- Zero tolerance

References

- ↑ Walsh, J. Michael; Gier, Johan J.; Christopherson, Asborg S.; Verstraete, Alain G. (11 August 2010). "Drugs and Driving". Traffic Injury Prevention. 5 (3): 241–253. doi:10.1080/15389580490465292. PMID 15276925. S2CID 23160488.

- ↑ Wanberg, Kenneth W.; Milkman, Harvey B.; Timkin, David S. (3 December 2004). Driving With Care:Education and Treatment of the Impaired Driving Offender-Strategies for Responsible Living: The Provider's Guide (1 ed.). Thousand Oaks, Calif.: SAGE Publications, Inc. p. 14. ISBN 9781412905961.

- ↑ "Magistrates' Court Sentencing Guidelines" (PDF). Sentencing Guidelines Council. May 2008. p. 188. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- 1 2 Merritt, Jonathan (9 July 2009). Law for Student Police Officers. SAGE. ISBN 9781844455638.

- ↑ Hannibal, Martin; Hardy, Stephen (4 March 2013). Practice Notes on Road Traffic Law 2/e. Routledge. pp. 57–68. ISBN 9781135346386.

- 1 2 Voas, Robert B.; Lacey, John H. "Issues in the enforcement of impaired driving laws in the United States". Pennsylvania State University. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.553.1031.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 Tekenos-Levy, Jordan (29 July 2015). "Impaired Driving in Canada: Cost and Effect of a Conviction". National College for DUI Defense. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ↑ "DUI | the crime of driving a vehicle while drunk also: a person who is arrested for driving a vehicle while drunk". Merriam-webster.com. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ↑ Rowling, Troy (14 October 2008). "In Mt Isa it's RUI: riding under the influence". Brisbane Times. Archived from the original on 15 October 2008. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ↑ "Pedestrian Safety". Police Department, University of Colorado. Archived from the original on 16 May 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2017. ("[I]f you bicycle while intoxicated you will be held to the same standards as other motorists and may be issued a DUI.")

- ↑ "Ore. skateboarder collides with van, charged with DUI". Crimesider. CBS News. 13 March 2013. Archived from the original on 7 February 2019. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ↑ Nelson, Bruce. "Nevada's Driving Under the Influence (DUI) laws". NVPAC. Advisory Council for Prosecuting Attorneys. Archived from the original on 22 April 2017. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ↑ "Florida DUI and Administrative Suspension Laws". FLHSMV. Florida Department of Highway Safety and Motor Vehicles. Archived from the original on 18 November 2021. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ↑ "Bill to change DUI marijuana impairment laws postponed". KMGH. 13 February 2019. Archived from the original on 15 March 2022. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ↑ National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). BAC Estimator [computer program]. Springfield, VA: National Technical Information Service, 1992.

- ↑ NHTSA (4 October 2016). "Drunk Driving – How Alcohol Affects Driving Ability". NHTSA. Archived from the original on 26 December 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ↑ Douglas Martin (reporter) (17 August 2002). "Robert F. Borkenstein, 89, Inventor of the Breathalyzer". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 March 2023. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

Robert F. Borkenstein, who revolutionized enforcement of drunken driving laws by inventing the Breathalyzer to measure alcohol in the blood, died last Saturday at his home in Bloomington, Ind. He was 89. ...Robert Frank Borkenstein was born in Fort Wayne, Ind., on Aug. 31, 1912.

- ↑ "Breathalyzer". USPTO. 13 May 1958. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2014.

- ↑ "Ethanol Level". Archived from the original on 23 July 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ "On DWI Laws in Other Countries". National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. March 2000. Archived from the original on 17 February 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ↑ Bates, Marsha E. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. "The Correspondence between Saliva and Breath Estimates of Blood Alcohol Concentration: Advantages and Limitations of the Saliva Method". Journal of Studies in Alcohol, 1 Jan. 1993. Web. 13 Mar. 2013.

- ↑ Tchir, Jason (10 June 2014). "How an impaired driving conviction can affect your car insurance rates". Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 14 May 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ↑ "The Medical Psychological Assessment: An Opportunity for the Individual, Safety for the Genera Public" (PDF). Archived from the original (PD) on 8 February 2012. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ↑ "Preventing road traffic injury: A public health perspective for Europe" (PDF). Euro.who.int. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- 1 2 Alonso, Francisco; Pasteur, Juan C.; Montero, Luis; Esteban, Cristina (2015). "Driving under the influence of alcohol: frequency, reasons, perceived risk and punishment". Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 10 (11): 11. doi:10.1186/s13011-015-0007-4. PMC 4359384. PMID 25880078.

- 1 2 "Impaired Driving | National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA)". Nhtsa.gov. Archived from the original on 3 October 2016. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ↑ "How Much Does A DUI Cost In 2022? – Forbes Advisor". www.forbes.com. Archived from the original on 27 April 2023. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- ↑ "Alcohol and Driving". Archived from the original on 21 June 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Grand Rapids Effects Revisited: Accidents, Alcohol and Risk Archived 7 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine, H.-P. Krüger, J. Kazenwadel and M. Vollrath, Center for Traffic Sciences, University of Wuerzburg, Röntgenring 11, D-97070 Würzburg, Germany

- ↑ Anum, EA; Silberg, J; Retchin, SM (2014). "Heritability of DUI convictions: a twin study of driving under the influence of alcohol". Twin Res Hum Genet. 17 (1): 10–5. doi:10.1017/thg.2013.86. PMID 24384043. S2CID 206345742.

- ↑ "Underage Drinking." National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/underagedrinking/underagefact.htm.

- ↑ "The Most Dangerous States for DUI Deaths". Your AAA Network. 7 January 2020. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

- ↑ "Driver Characteristics and Impairment at Various BACs – Introduction". one.nhtsa.gov. Archived from the original on 28 October 2020. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- ↑ Robert F. Borkenstein papers, 1928–2002 Archived 26 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Indiana U. The role of the drinking driver in traffic accidents Archived 13 February 2023 at the Wayback Machine (Researchgate link)

- ↑ Center for Studies of Law in Action, Robert F. Borkenstein Courses Archived 2019-08-01 at the Wayback Machine, Indiana U.

- ↑ Mostile G; Jankovic J (October 2010). "Alcohol in essential tremor and other movement disorders". Movement Disorders. 25 (14): 2274–84. doi:10.1002/mds.23240. PMID 20721919. S2CID 39981956.

- ↑ Drug Evaluation and Classification Program. NHTSA. pp. Sev IV Pg. 5–6.

- ↑ DECP Annual Report.pdf "Drug Evaluation and Classification Program (DECP) Annual Report 2018" (PDF). International Association of Chiefs of Police. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help)CS1 maint: url-status (link) - 1 2 "National Post". News.nationalpost.com. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- 1 2 3 "Ontario to bring in stronger punishment for driving under influence of drugs". Ca.news.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- 1 2 3 "Marijuana and Driving — Colorado Department of Transportation". Codot.gov. Archived from the original on 15 October 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ↑ Kaye, Adam M. (12 January 2013). "Basic Concepts in Opioid Prescribing and Current Concepts of Opioid-Mediated Effects on Driving". The Ochsner Journal. 13 (4): 525–32. PMC 3865831. PMID 24358001.

- 1 2 Sigona, Nicholas (13 October 2014). "Driving Under the Influence, Public Policy, and Pharmacy Practice". Journal of Pharmacy Practice. 28 (1): 119–123. doi:10.1177/0897190014549839. PMID 25312259. S2CID 45295600. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - 1 2 3 American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine (February 2014), "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, archived from the original on 11 September 2014, retrieved 24 February 2014, which cites

- Weiss, MS; Bowden, K; Branco, F; et al. (2011). "Opioids Guideline". In Kurt T. Hegmann (ed.). Occupational medicine practice guidelines : evaluation and management of common health problems and functional recovery in workers (online March 2014) (3rd ed.). Elk Grove Village, IL: American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. p. 11. ISBN 978-0615452272.

- ↑ "The proactive role employers can take: Opioids in the Workplace" (PDF). National Safety Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ↑ "Standardized Field Sobriety Test (SFST) Validated at BACS Below 0.10 Percent | National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA)". Nhtsa.gov. Archived from the original on 1 March 2016. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- 1 2 DUI: Refusal to Take a Field Test, or Blood, Breath or Urine Test Archived 6 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine, NOLO Press

- ↑ "SOS - Substance Abuse and Driving". Michigan.gov. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ↑ Committee, Oregon Legislative Counsel. "ORS 813.136 (2015) – Consequence of refusal or failure to submit to field sobriety tests". Archived from the original on 26 April 2021. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- ↑ Walsh, J. Michael (2009). "A State-by-State Analysis of Laws Dealing With Driving Under the Influence of Drugs" (PDF). ems.gov. NHTSA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- 1 2 3 "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "Marijuana-Impaired Driving : A Report to Congress" (PDF). Nhtsa.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 March 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ↑ Smith, Aaron (26 May 2017). "These companies are racing to develop a Breathalyzer for pot". Money.cnn.com. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ↑ "Child Endangerment Drunk Driving Laws" (PDF). MADD. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ↑ Graham, Kyle (2011). "Facilitating Crimes: An Inquiry into the Selective Invocation of Offenses within the Continuum of Criminal Procedures". Lewis & Clark Law Review. 15: 667.

- ↑ Anonymous (17 October 2016). "The legal limit". Mobility and transport – European Commission. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- ↑ "Supreme Court of Canada – Decisions – Criminal Law Amendment Act, Reference". Scc.lexum.org. 26 June 1970. Archived from the original on 5 May 2012. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ↑ McLeod, Ken (11 July 2013). "Bike Law University: Riding Under the Influence". League of American Bicyclists. Archived from the original on 13 February 2023. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- ↑ "Actions Resulting In Loss Of License Alcohol Impairment Charts" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 May 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ↑ "DUI Sentencing Grid" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 February 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ↑ Gus Chan, The Plain Dealer (10 January 2011). "Cuyahoga County Council's finalists for boards of revision include employee with criminal past". Blog.cleveland.com. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ↑ Wales, Transport for New South (3 February 2016). "Blood alcohol limits". roadsafety.transport.nsw.gov.au. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- ↑ "Drink driving penalties". Findlaw.com.au. Archived from the original on 6 January 2023. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- ↑ Dickson, Louise. "Breath test can't be refused under new drunk-driving law". Times Colonist. Archived from the original on 19 September 2021. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- ↑ Pauls, Karen (22 November 2018). "'A lot of people facing potential deportation' under upcoming changes to DUI penalties: immigration lawyer". CBC. Archived from the original on 6 March 2021. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- ↑ "Entering Canada With A DUI | FAQ | Infographics". Immigly. 15 April 2021. Archived from the original on 6 April 2023. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- ↑ What are my rights if the police think I've been taking drugs and driving? Archived 13 February 2023 at the Wayback Machine, Steps to Justice (advises that FST is mandatory)

- ↑ [Breathalyzer and roadside tests (Ont.)], legalline.ca

- ↑ Alcohol and Drug Impaired Driving – Tests, Criminal Charges, Penalties, Suspensions and Prohibitions Archived 16 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine – RCMP

- ↑ What must I legally do when police pull me over? Archived 5 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine, Globe and Mail, 4-Aug-2015

- ↑ "Consolidated federal laws of canada, Criminal Code". Laws-lois.justice.gc.ca. 8 April 2019. Archived from the original on 6 April 2023. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- ↑ "Impaired driving". Mto.gov.on.ca. 12 July 2019. Archived from the original on 14 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ↑ "Alcohol and drug related driving prohibitions and suspensions". Province of British Columbia. Archived from the original on 13 February 2023. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ↑ "Criminal Code". Laws-lois.justice.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ↑ Toplak, Jurij (20 May 2020). "The ECHR and the right to have a criminal record and a drink-drive history erased". Strasbourg Observers. Archived from the original on 6 April 2023. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- ↑ "국가법령정보센터". Law.go.kr (in 한국어). Archived from the original on 29 December 2019. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ↑ "He was killed 15 meters by a drunk car, and the perpetrator was sentenced to three years in prison?". Archived from the original on 23 April 2023. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- ↑ "The drink drive limit". GOV.UK. Archived from the original on 3 October 2012. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ↑ "Drink-driving penalties". GOV.UK. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ↑ Waugh, Rob (12 May 2015). "How UK's new drug-driving laws really work – as first drivers are charged". Metro. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ↑ Adams, Lucy (21 April 2017). "Drug-driving limits and roadside testing to be introduced". BBC. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ↑ "Drunken / Impaired Driving". NCSL. National Conference of State Legislatures. Archived from the original on 3 October 2017. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- ↑ "California Vehicle Code, Sec. 23152". California Legislative Information. California State Legislature. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ↑ "Sleeping while drunk in the driver's seat of a parked car with the engine running is driving under the influence, and you really should have known that". Public Defender Service for the District of Columbia. 22 January 2015. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ↑ Sarantis, Theo (29 August 2012). "Drunk in the Backseat of a Car? You Could Get a D.U.I." Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 15 December 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ↑ Reff, Robert S. (2013). Drunk Driving and Related Vehicular Offenses. LexisNexis. p. 125. ISBN 978-1579111144. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ↑ Thompson, Conness A. "Felony DUI Cases at a Glance" (PDF). Central California Appellate Program. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ↑ Rosich, Katherine J.; Kane, Kamala M. "Truth in Sentencing and State Sentencing Practices". National Institute of Justice. Office of Justice Programs. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- ↑ Lyons, Jenna (January 2018). "Some states put a THC limit on pot-smoking drivers — Here's why California doesn't". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 2 February 2019. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- ↑ Rahaim, Nick (8 January 2018). "No chemical threshold to mark marijuana impairment for California drivers". Business Journal. Archived from the original on 31 December 2019. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- ↑ Four in Ten Criminal Offenders Report Alcohol as a Factor in Violence: But Alcohol-Related Deaths and Consumption in Decline Archived 2011-01-18 at the Wayback Machine, April 5, 1998, United States Bureau of Justice Statistics.

- ↑ DWI Offenders under Correctional Supervision Archived 2011-08-11 at the Wayback Machine, June 1999, United States Bureau of Justice Statistics.

- ↑ "Impaired Driving: Get the Facts". CDC. 16 June 2017. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- 1 2 Grand Rapids Effects Revisited: Accidents, Alcohol and Risk Archived 7 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine, H.-P. Krüger, J. Kazenwadel and M. Vollrath, Center for Traffic Sciences, University of Wuerzburg, Röntgenring 11, D-97070 Würzburg, Germany.

- 1 2 Crash Risk of Alcohol Involved Driving: A Case-Control Study Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Blomberg, Richard D; Peck, Raymond C; Moskowitz, Herbert; Burns, Marcelline; Fiorentino, Dary. Abstract Archived 6 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine. Dunlap and Associates, Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2005. Mainly pages xviii and 108.

- ↑ Soronen, Lisa. "Blood Alcohol Testing: No Consent, No Warrant, No Crime?". NCSL. National Conference of State Legislatures. Archived from the original on 10 October 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- ↑ "Kansas DUI law that makes test refusal a crime is ruled unconstitutional". kansascity. Archived from the original on 11 April 2017. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ↑ "Michigan's Law". Michigan.gov. Archived from the original on 16 August 2019. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ↑ "Alcohol and Drug Testing Regulations (Parts 219 and 40) Interpretive Guidance Manual". Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 January 2015. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ↑ "UNION PACIFIC RAILROAD DRUG AND ALCOHOL POLICY Effective October 1, 2013 (see section 5.1.2)" (PDF). Ble-t.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

Further reading

- Barron H. Lerner (2011). One for the Road: Drunk Driving Since 1900. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

External links

- Impaired driving Archived 4 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine on MedlinePlus