Vibegron

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Gemtesa |

| Other names | RVT-901; MK4618; KRP114V; URO-901 |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Beta3 adrenergic receptor agonist |

| Main uses | Overactive bladder[1] |

| Side effects | Headache, urinary tract infection, diarrhea, nausea, upper respiratory tract infection[1] |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Routes of use | By mouth |

| Typical dose | 75 mg OD[2] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Legal | |

| License data | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Protein binding | 49.6 to 51.3% is bound to plasma proteins [3] |

| Metabolism | Predominantly oxidation and glucuronidation [3] |

| Elimination half-life | 60 to 70 hours [3] |

| Excretion | 59% feces (54% of this is in the unchanged parent drug form), 20% urine (19% of this is in the unchanged parent drug form) [4] |

| Chemical and physical data | |

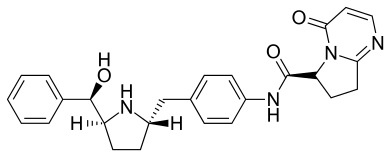

| Formula | C26H28N4O3 |

| Molar mass | 444.535 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Vibegron, sold under the brand name Gemtesa, is a medication used to treat overactive bladder.[1][5] It is used to improve the symptoms of urinary incontinence, urgency, and urinary frequency.[1] It is taken by mouth.[1]

Common side effects include headache, urinary tract infection, diarrhea, nausea, and upper respiratory tract infection.[1] Other side effects may include urinary retention.[1] Use is not recommended in people with severe kidney or liver problems.[1] Safety in pregancy is unclear.[1] It is a selective beta3 adrenergic receptor agonist.[2]

Vibegron was approved for medical use in Japan in 2018 and the United States in 2020.[1][6] It is not approved in the United Kingdom or Europe as of 2022.[6] In the United States it costs about 460 USD per month as of 2022.[7]

Medical uses

Vibegron is indicated for the treatment of overactive bladder with symptoms of urge urinary incontinence, urgency, and urinary frequency in adults.[1][5]

Vibegron treatment should be discontinued if urinary retention occurs. Use with nonselective muscarinic antagonists may increase the risk of urinary retention. The manufacturer suggests discontinuing vibegron if an elevated digoxin concentration occurs.[4]

Efficacy

Vibegron was evaluated in patients with overactive bladder (OAB) in several studies. A controlled study, called Empower, showed the beneficial effects of the drug to treat the condition and UUI.[4][3] Primary outcomes of different trials showed there was an overall increase in efficacy. These outcomes concluded that there was a reduction in urgency to urinate, a decrease in micturitions and a decrease in average volume voided per micturition.[4] There is also an improvement observed of the symptoms when it is administered over a longer period (52 weeks) concluding that it is effective and safe for longer use.[8] In severe systems, increasing the dose was accompanied by similar beneficial effects when there was first a lack of these.[9] Quality of life is improved, including a reduction of nocturia.[8]

Dosage

The typical dose is 75 mg once per day.[2]

Side effects

The most common side effects are a dry mouth, constipation, headache, nasopharyngitis, diarrhea, nausea, bronchitis, urinary tract infection and upper respiratory tract infection. An indication is made that upon urinary retention development, the patient should stop using the drug. Risk assessment for the drug in pregnant women has yet to be evaluated.[4]

Pregnancy

Pregnant rats were given very high daily oral doses of Vibegron during the period of organogenesis and showed no embryo-fetal developmental toxicity up to 300 mg/kg/day. Similar data was found in rabbits. Maternal toxicity was observed when doses exceeded 100 mg/kg/day in lactating rats. Clinical studies show that Vibegron is not toxic, safe and well-tolerated in patients.[4]

Interactions

Vibegron is in contrast to other OAB drugs very selective and leads to a lesser degree in unwanted side effects. Vibegron is found to be a substrate for CYP3A4 in vivo, but does not actually induce or inhibit any of the cytochrome P450 enzymes and is thus less likely to take part in drug–drug interactions (DDI). Here vibegron differs from the previous overactive bladder drug mirabegron, which was known to be associated in various drug–drug interactions by inhibiting CYP2D6 or inducing CYP3A4, CYP2D6 and CYP2C9 in the liver.[10][3][11][12][13][8]

Using Vibegron only (monotherapy) has positive effects on OAB and UUI, but a combination with other drugs can have additional effects. In a study with antimuscarinic drugs, more DDIs were investigated using a model of Rhesus monkeys. Dose combinations of vibegron and tolterodine showed increased bladder capacity, the effects of both drugs at low dosis strengthened each other, known as synergism. The addition of darifenacin to vibegron created greater bladder relaxation only when used at high doses.[14] Additionally, co-administration with Imidafenacin shows an increase in bladder capacity and voided volume in comparison to monotherapy.[14] Possibly, a widely adapted treatment will be the combination of beta-3-adrenergic agonist with a nonselective M2/M3 antagonist as the most prevalent option.[3]

Clinical studies show no significant drug–drug interaction (DDI), aside from a serum concentration increase of digoxin when taken with vibegron. Maximal concentrations and systemic exposure (Cmax and area under the curve (AUC)) of digoxin are both increased as a result of DDI.[15][4] Apart from the no to little DDIs, Vibegron has an additional safety quality in that it does not cross the blood-brain barrier and therefore does not induce cognitive impairment.[3] Furthermore, Vibegron can be taken with or without food, this does not have an effect on vibegron plasma concentrations.[4][15]

Mechanism of action

Vibegron is a selective agonist for the beta-3 adrenergic receptor (β3-AR). The receptors are located in the kidneys, urinary tract and bladder tissue.[16] Upon binding, the β3 receptor undergoes a conformational change. This induces the activation of adenylate cyclases via G proteins and thereby promotes the formation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). The consequence of this cascade is an increased intracellular cAMP concentration which triggers activation of cAMP-dependent protein kinase A and causes a reduction of Ca2+ concentration in the cytoplasm. The kinase then phosphorylates myosin chains and thereby inhibits muscle contraction.[3]

The final effect of vibegron is muscle relaxation in the bladder. Due to this muscle relaxation, bladder capacity increases and symptoms of overactive bladder are relieved.[8]

Metabolism

The two main metabolic pathways are the oxidation and glucuronidation of vibegron. Two oxidative metabolites and three glucuronide metabolites can be formed. The exact structure of these metabolites have not been studied yet.[3] In vitro, CYP3A4 is the enzyme responsible for the metabolism of vibegron, facilitating oxidative metabolism. Eventually, still a large part of the unmodified drug is excreted through feces and urine.[4]

History

The beta 3 adrenergic receptor was discovered in the late 1980s[16] and initially beta3AR agonists were investigated as treatment for obesity and diabetes.[17] A number of compounds were tested in clinical trials but didn't show sufficient benefits in these areas.[17]

Since the 2000s there is evidence that there are beta3AR on the detrusor muscle of the bladder.[17] The detrusor muscle contracts during urination and remains relaxed to allow the bladder to store urine.

Mirabegron was the first FDA approved selective agonist approved to treat overactive bladder (OAB).[16]

Vibegron is a selective beta3AR agonist that is developed in Japan by Kyorin Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd and Kissei Pharmaceutical Co.,Ltd and Urovant Sciences to treat overactive bladders and pain caused by irritable bowel syndrome.[18] It was globally approved on September 21, 2018, in Japan for OAB.[18]

Vibegron has been proven effective in 5 key clinical trials.[18]

A phase IIb global trial completed in 2013 of 1395 patients, of which 89.7% were women and 63.3% had not been treated previously, demonstrated a significant decrease in daily micturitions and urgent urinary incontinence episodes upon administration of vibegron.[19][10]

An international phase III trial of 506 participants completed in 2019 found statistically significant efficacy of vibegron after 2 weeks of daily administration. The adverse effect rates in patients treated with vibegron were comparable to those in patients who received a placebo.[20]

GEMTESA, a drug using vibegron as an active ingredient was approved by the FDA on December 23, 2020, after an additional phase III international trial of 1085 patients.[5]

Society and culture

Legal status

Vibegron was approved for medical use in the United States in December 2020.[1][5]

Names

Vibegron is the international nonproprietary name (INN).[21]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "Gemtesa- vibegron tablet, film coated". DailyMed. Archived from the original on 14 January 2021. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- 1 2 3 "Vibegron Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Rechberger T, Wróbel A (January 2021). "Evaluating vibegron for the treatment of overactive bladder". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 22 (1): 9–17. doi:10.1080/14656566.2020.1809652. ISSN 1465-6566. PMID 32993398. S2CID 222166213. Archived from the original on 2021-07-17. Retrieved 2022-09-15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Urovant Sciences GmbH (2020). "HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION GEMTESA" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-07-17. Retrieved 2022-09-15.

- 1 2 3 4 "Drug Trials Snapshot: Gemtesa". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 23 December 2020. Archived from the original on 12 January 2021. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - 1 2 "Vibegron". SPS - Specialist Pharmacy Service. 25 January 2016. Archived from the original on 4 December 2021. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- ↑ "Gemtesa". Archived from the original on 1 November 2022. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 Yoshida M, Takeda M, Gotoh M, Yokoyama O, Kakizaki H, Takahashi S, et al. (March 2019). "Efficacy of novel β3 -adrenoreceptor agonist vibegron on nocturia in patients with overactive bladder: A post-hoc analysis of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study". International Journal of Urology. 26 (3): 369–375. doi:10.1111/iju.13877. PMC 6912249. PMID 30557916.

- ↑ Yoshida M, Takeda M, Gotoh M, Nagai S, Kurose T (May 2018). "Vibegron, a Novel Potent and Selective β3-Adrenoreceptor Agonist, for the Treatment of Patients with Overactive Bladder: A Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Phase 3 Study". European Urology. 73 (5): 783–790. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2017.12.022. PMID 29366513.

- 1 2 Mitcheson HD, Samanta S, Muldowney K, Pinto CA, Rocha BA, Green S, et al. (February 2019). "Vibegron (RVT-901/MK-4618/KRP-114V) Administered Once Daily as Monotherapy or Concomitantly with Tolterodine in Patients with an Overactive Bladder: A Multicenter, Phase IIb, Randomized, Double-blind, Controlled Trial". European Urology. 75 (2): 274–282. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2018.10.006. PMID 30661513.

- ↑ Stambakio H (2019). "AUA 2019: Once-Daily Vibegron, a Novel Oral β3 Agonist Does Not Inhibit CYP2D6, a Common Pathway For Drug Metabolism in Patients on OAB Medications". Archived from the original on 2021-07-19. Retrieved 2022-09-15.

- ↑ Bragg R, Hebel D, Vouri SM, Pitlick JM (December 2014). "Mirabegron: a Beta-3 agonist for overactive bladder". The Consultant Pharmacist. 29 (12): 823–37. doi:10.4140/TCP.n.2014.823. PMC 4605389. PMID 25521658.

- ↑ Araklitis G, Baines G, da Silva AS, Robinson D, Cardozo L (2020-09-11). "Recent advances in managing overactive bladder". F1000Research. 9: 1125. doi:10.12688/f1000research.26607.1. PMC 7489273. PMID 32968482. Archived from the original on 2022-06-18. Retrieved 2022-09-15.

- 1 2 Di Salvo J, Nagabukuro H, Wickham LA, Abbadie C, DeMartino JA, Fitzmaurice A, et al. (February 2017). "Pharmacological Characterization of a Novel Beta 3 Adrenergic Agonist, Vibegron: Evaluation of Antimuscarinic Receptor Selectivity for Combination Therapy for Overactive Bladder". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 360 (2): 346–355. doi:10.1124/jpet.116.237313. PMID 27965369. Archived from the original on 2022-07-29. Retrieved 2022-09-15.

- 1 2 Medscape. "vibegron (Rx)". Archived from the original on 2022-05-22. Retrieved 2022-09-15.

- 1 2 3 Schena G, Caplan MJ (April 2019). "Everything You Always Wanted to Know about β3-AR * (* But Were Afraid to Ask)". Cells. 8 (4): 357. doi:10.3390/cells8040357. PMC 6523418. PMID 30995798.

- 1 2 3 Edmondson SD, Zhu C, Kar NF, Di Salvo J, Nagabukuro H, Sacre-Salem B, et al. (January 2016). "Discovery of Vibegron: A Potent and Selective β3 Adrenergic Receptor Agonist for the Treatment of Overactive Bladder". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 59 (2): 609–23. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01372. PMID 26709102.

- 1 2 3 Keam SJ (November 2018). "Vibegron: First Global Approval". Drugs. 78 (17): 1835–1839. doi:10.1007/s40265-018-1006-3. PMID 30411311. S2CID 53212220. Archived from the original on 2022-11-01. Retrieved 2022-09-15.

- ↑ Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. (March 15, 2011). "A Study of the Efficacy and Safety of Vibegron (MK-4618) in Participants With Overactive Bladder (OAB) (MK-4618-008)". Archived from the original on July 17, 2021. Retrieved September 15, 2022.

- ↑ Urovant Sciences GmbH (July 11, 2018). "An Extension Study to Examine the Safety and Tolerability of a New Drug in Patients With Symptoms of Overactive Bladder (OAB). (Empowur)". Archived from the original on July 17, 2021. Retrieved September 15, 2022.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ World Health Organization (2013). "International nonproprietary names for pharmaceutical substances (INN): recommended INN: list 70". WHO Drug Information. 27 (3): 318. hdl:10665/331167.

External links

| External sites: |

|

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |

- Clinical trial number NCT03492281 for "A Study to Examine the Safety and Efficacy of a New Drug in Patients With Symptoms of Overactive Bladder (OAB) (Empowur)" at ClinicalTrials.gov