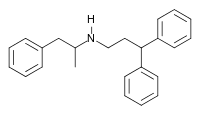

Prenylamine

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | N-(3,3-diphenylpropyl)amphetamine |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.006.246 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C24H27N |

| Molar mass | 329.487 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| | |

Prenylamine (Segontin) is a calcium channel blocker of the amphetamine chemical class that was used as a vasodilator in the treatment of angina pectoris.

History

Prenylamine was introduced in the 1960s by German manufacturer Albert-Roussel pharma gmbh,[1][2] which was acquired by Hoechst AG in 1974 and which in turn became part of Sanofi Aventis in 2005.

It was withdrawn from market worldwide in 1988 because it caused QT interval prolongation and torsades de pointes, greatly increasing the risk of sudden death.[1][3] The cardiac side effects were not detected during clinical development, only becoming apparent after the drug was in wide use.[1]

Mechanism of action

Prenylamine has two primary molecular targets in humans: calmodulin and myosin light-chain kinase 2, found in skeletal and cardiac muscle.[4] Pharmacologically, it decreases sympathetic stimulation on cardiac muscle, predominantly through partial depletion of catecholamines via competitive inhibition of reuptake by storage granules, leading to further depletion due to spontaneous leakage as a result of disturbance of equilibrium.[5] This depletion mechanism is similar to that of reserpine because both agents target the same site on the storage granule; however, prenylamine shows a high affinity for cardiac tissue, while reserpine is more selective toward brain tissue.[6]

Prenylamine slows cardiac metabolism via calcium transport delay by blockade of magnesium-dependent calcium transport ATPase. It demonstrate beta blocker–like activity that results in reduction of heart rate but shows an opposing effect on tracheal tissue response.[5]

References

- 1 2 3 Shah RR (2007). "Withdrawal of Terodiline: A Tale of Two Toxicities". In Mann RD, Andrews EB (eds.). Pharmacovigilance (2nd ed.). Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons. p. 116. ISBN 9780470059227.

- ↑ Godfraind T, Herman AG, Wellens D (2012). Calcium Entry Blockers in Cardiovascular and Cerebral Dysfunctions. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 40. ISBN 978-9400960336 – via google books.

- ↑ Fung M, Thornton A, Mybeck K, Wu JH, Hornbuckle K, Muniz E (2001-01-01). "Evaluation of the Characteristics of Safety Withdrawal of Prescription Drugs from Worldwide Pharmaceutical Markets-1960 to 1999*". Drug Information Journal. 35 (1): 293–317. doi:10.1177/009286150103500134. ISSN 2168-4790. S2CID 73036562.

- ↑ "Prenylamine". DrugBank. 2016-08-17.

- 1 2 Murphy, J. Eric (1973-03-01). "Drug Profile: Synadrin". Journal of International Medical Research. 1 (3): 204–209. doi:10.1177/030006057300100312. ISSN 0300-0605. S2CID 74503460.

- ↑ Obianwu HO (1965-04-01). "The effect of prenylamine (segontin) on the amine levels of brain, heart and adrenal medulla in rats". Acta Pharmacologica et Toxicologica. 23 (4): 383–90. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0773.1965.tb00362.x. PMID 5899695.