Autoimmune pancreatitis

| Autoimmune pancreatitis | |

|---|---|

| Other names: AIP | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology |

| Symptoms | Painless jaundice, pancreatic mass |

| Types | Type 1 and Type 2 |

| Causes | IgG4-related disease |

| Diagnostic method | Biopsy, imaging, serology |

| Differential diagnosis | Pancreatic cancer |

| Treatment | Corticosteroids (first line), azathioprine, rituximab |

Autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) is an increasingly recognized type of chronic pancreatitis that can be difficult to distinguish from pancreatic carcinoma but which responds to treatment with corticosteroids, particularly prednisone.[1] Although autoimmune pancreatitis is quite rare, it constitutes an important clinical problem for both patients and their clinicians: the disease commonly presents itself as a tumorous mass which is diagnostically indistinguishable from pancreatic cancer, a disease that is much more common in addition to being very dangerous. Hence, some patients undergo pancreatic surgery, which is associated to substantial mortality and morbidity, out of the fear by patients and clinicians to undertreat a malignancy. However, surgery is not a good treatment for this condition as AIP responds well to immunosuppressive treatment. There are two categories of AIP: Type 1 and Type 2, each with distinct clinical profiles.

Type 1 AIP is now regarded as a manifestation of IgG4-related disease,[2] and those affected have tended to be older and to have a high relapse rate. Type 1 is associated with pancreatitis, Sjogren syndrome, Primary sclerosing cholangitis and Inflammatory bowel disease. Patients with Type 2 AIP do not experience relapse, tend to be younger and not associated with systemic disease. AIP occurring in association with an autoimmune disorder has been referred to as "secondary" or "syndromic" AIP. AIP does not affect long-term survival.[3]

Signs and symptoms

Autoimmune pancreatitis may cause a variety of symptoms and signs, which include pancreatic and biliary (bile duct) manifestations, as well as systemic effects of the disease. Two-thirds of patients present with either painless jaundice due to bile duct obstruction or a "mass" in the head of the pancreas, mimicking carcinoma. As such, a thorough evaluation to rule out cancer is important in cases of suspected AIP.[4]

Type 1 AIP typically presents in a 60–70 year old male with painless jaundice. In some cases, imaging reveals a mass in the pancreas or diffuse pancreatic enlargement.[4] Narrowing in the pancreatic duct called strictures may occur.[4] Rarely, Type 1 AIP presents with acute pancreatitis.[4] Type 1 AIP presents with manifestations of autoimmune disease (IgG4 related) in at least half of cases. The most common form of systemic involvement is cholangitis, which occurs in up to 80 percent of cases of Type 1 AIP. Additional manifestations include inflammation in the salivary glands (Sjögren syndrome), in the lungs resulting in scarring (pulmonary fibrosis) and nodules, scarring within the chest cavity (mediastinal fibrosis) or in the anatomic space behind the abdomen (retroperitoneal fibrosis) and inflammation in the kidneys (tubulointerstitial nephritis).[4]

AIP is characterized by the following features:

- Scleral Icterus (yellow eyes), jaundice (yellow skin) which is usually painless, usually without acute attacks of pancreatitis.

- Relatively mild symptoms, such as minimal weight loss or nausea.

- Increased serum levels of gamma globulins, immunoglobulin G (IgG) or IgG4.

- The presence of serum autoantibodies such as anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), anti-lactoferrin antibody, anti-carbonic anhydrase II antibody, and rheumatoid factor (RF).

- Contrast-enhanced CT demonstrates a diffusely enlarged (sausage-shaped) pancreas.

- Diffuse irregular narrowing of the main pancreatic duct, and stenosis of the intrapancreatic bile duct on endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).

- Rare pancreatic calcification or cyst formation.

- Marked responsiveness to treatment with corticosteroids.

Histopathology

Histopathologic examination of the pancreas reveals a characteristic lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate of CD4- or CD8-positive lymphocytes and IgG4-positive plasma cells, and exhibits interstitial fibrosis and acinar cell atrophy in later stages. At the initial stages, typically, there is a cuff of lymphoplasma cells surrounding the ducts but also more diffuse infiltration in the lobular parenchyma. However, localization and the degree of duct wall infiltration are variable. Whereas histopathologic examination remains the primary method for differentiation of AIP from acute and chronic pancreatitis, lymphoma, and cancer. By Fine Needle Aspiration (FNA) the diagnosis can be made if adequate tissue is obtained. In such cases, lymphoplasmacytic infiltration of the lobules are the key finding. Rarely, granulomatous reaction could be observed. It has been proposed that a cytologic smear primarily composed of acini rich in chronic inflammatory cells (lymphocytes, plasma cells), with rare ductal epithelial cells lacking atypia, favors the diagnosis of AIP. The sensitivity and the specificity of these criteria for differentiating AIP from neoplasia are unknown. In cases of systemic manifestation of AIP, the pathologic features are similar in other organs.[5]

Although the exact mechanism explaining the clinical manifestations of autoimmune pancreatitis remain for an important part obscure, most professionals would agree that the development of IgG4 antibodies, recognizing an epitiope on the membrane of pancreatic ancinar cells is an important factor in the pathophysiology of the disease. These antibodies are postulated to provoke an immune response against these ancinar cells resulting in pancreatic inflammation and destruction.[5] Knowing the auto-antigens involved would allow early diagnosis of the disease, its differentiation from a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer, and potentially even prevention, but unfortunately these remain obscure. An earlier publication suggested that the human ubiquitin-protein ligase E3 component n-recognin 2 (UBR2) was an important antigen [6] but follow up studies suggested this finding is likely to be an artifact.[7] Hence improved diagnosis, understanding and treatment of autoimmune pancreatitis awaits the identification of the auto-antigens involved.

Diagnosis

Criteria

Most recently the fourteenth Congress of the International Association of Pancreatology developed the International Consensus Diagnostic Criteria (ICDC) for AIP. The ICDC emphasizes five cardinal features of AIP which includes the imaging appearance of pancreatic parenchyma and the pancreatic duct, serum IgG4 level, other organ involvement with IgG4-related disease, pancreatic histology and response to steroid therapy.[8]

In 2002, the Japanese Pancreas Society proposed the following diagnostic criteria for autoimmune pancreatitis:

- I. Pancreatic imaging studies show diffuse narrowing of the main pancreatic duct with irregular wall (more than 1/3 of length of the entire pancreas).

- II. Laboratory data demonstrate abnormally elevated levels of serum gamma globulin and/or IgG, or the presence of autoantibodies.

- III. Histopathologic examination of the pancreas shows fibrotic changes with lymphocyte and plasma cell infiltrate.

For diagnosis, criterion I (pancreatic imaging) must be present with criterion II (laboratory data) and/or III (histopathologic findings).[9]

Mayo Clinic has come up with five diagnostic criteria called HISORt criteria which stands for histology, imaging, serology, other organ involvement, and response to steroid therapy.[10]

Radiologic features

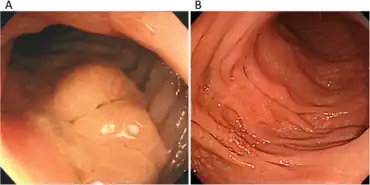

Computed tomography (CT) findings in AIP include a diffusely enlarged hypodense pancreas or a focal mass that may be mistaken for a pancreatic malignancy.[8] A low-density, capsule-like rim on CT (possibly corresponding to an inflammatory process involving peripancreatic tissues) is thought to be an additional characteristic feature (thus the mnemonic: sausage-shaped). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) reveals a diffusely decreased signal intensity and delayed enhancement on dynamic scanning. The characteristic ERCP finding is segmental or diffuse irregular narrowing of the main pancreatic duct, usually accompanied by an extrinsic-appearing stricture of the distal bile duct. Changes in the extrapancreatic bile duct similar to those of primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) have been reported.

The role of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) in the diagnosis of AIP is not well described, and EUS findings have been described in only a small number of patients. In one study, EUS revealed a diffusely swollen and hypoechoic pancreas in 8 of the 14 (57%) patients, and a solitary, focal, irregular mass was observed in 6 (46%) patients. Whereas EUS-FNA is sensitive and specific for the diagnosis of pancreatic malignancy, its role in the diagnosis of AIP remains unclear.

Treatment

AIP often completely resolves with steroid treatment. The failure to differentiate AIP from malignancy may lead to unnecessary pancreatic resection, and the characteristic lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate of AIP has been found in up to 23% of patients undergoing pancreatic resection for suspected malignancy who are ultimately found to have benign disease. In this subset of patients, a trial of steroid therapy may have prevented a Whipple procedure or complete pancreatectomy for a benign disease which responds well to medical therapy.[11] "This benign disease resembles pancreatic carcinoma both clinically and radiographically. The diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis is challenging to make. However, accurate and timely diagnosis may preempt the misdiagnosis of cancer and decrease the number of unnecessary pancreatic resections."[12] Autoimmune pancreatitis responds dramatically to corticosteroid treatment.[12]

If relapse occurs after corticosteroid treatment or corticosteroid treatment is not tolerated, immunomodulators may be used. Immunomodulators such as azathioprine, and 6-mercaptopurine have been shown to extend remission of autoimmune pancreatitis after corticosteroid treatment. If corticosteroid and immunomodulator treatments are not sufficient, rituximab may also be used. Rituximab has been shown to induce and maintain remission.[13]

Prognosis

AIP does not affect long-term survival.[3]

Epidemiology

AIP is relatively uncommon,[14] with an overall global prevalence less than 1 per 100,000. Type 1 AIP is more common in East Asia, whereas type 2 is relatively more common in the US and Europe. The prevalence of AIP may be increasing in Japan.[15] Type 1 AIP occurs three times more often in men than women.[4]

Controversies in nomenclature

As the number of published cases of AIP has increased, efforts have been focused on defining AIP as a distinct clinical and pathologic entity and toward developing some generally agreed upon diagnostic criteria and nomenclature. Terms frequently encountered are autoimmune or autoimmune-related pancreatitis, lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis, idiopathic tumefactive chronic pancreatitis, idiopathic pancreatitis with focal irregular narrowing of the main pancreatic duct, and non-alcoholic duct destructive chronic pancreatitis. There are also a large number of case reports employing descriptive terminology such as pancreatitis associated with Sjögren’s syndrome, primary sclerosing cholangitis, or inflammatory bowel disease. Some of the earliest cases were reported as pancreatic pseudotumor or pseudolymphoma.

References

- ↑ Rose, Noel R.; Mackay, Ian R. (2006). The autoimmune diseases (4th ed.). Academic Press. p. 783. ISBN 978-0-12-595961-2.

- ↑ Stone, John H.; Khosroshahi, Arezou; Deshpande, Vikram; Chan, John K. C.; Heathcote, J. Godfrey; Aalberse, Rob; Azumi, Atsushi; Bloch, Donald B.; Brugge, William R.; Carruthers, Mollie N.; Cheuk, Wah; Cornell, Lynn; Castillo, Carlos Fernandez-Del; Ferry, Judith A.; Forcione, David; Klöppel, Günter; Hamilos, Daniel L.; Kamisawa, Terumi; Kasashima, Satomi; Kawa, Shigeyuki; Kawano, Mitsuhiro; Masaki, Yasufumi; Notohara, Kenji; Okazaki, Kazuichi; Ryu, Ji Kon; Saeki, Takako; Sahani, Dushyant; Sato, Yasuharu; Smyrk, Thomas; Stone, James R.; Takahira, Masayuki; Umehara, Hisanori; Webster, George; Yamamoto, Motohisa; Yi, Eunhee; Yoshino, Tadashi; Zamboni, Giuseppe; Zen, Yoh; Chari, Suresh (2012). "Recommendations for the nomenclature of IgG4-related disease and its individual organ system manifestations". Arthritis & Rheumatism. 64 (10): 3061–7. doi:10.1002/art.34593. PMC 5963880. PMID 22736240.

- 1 2 Sah, Raghuwansh P.; Chari, Suresh T.; Pannala, Rahul; Sugumar, Aravind; Clain, Jonathan E.; Levy, Michael J.; Pearson, Randall K.; Smyrk, Thomas C.; Petersen, Bret T.; Topazian, Mark D.; Takahashi, Naoki; Farnell, Michael B.; Vege, Santhi S. (2010). "Differences in Clinical Profile and Relapse Rate of Type 1 Versus Type 2 Autoimmune Pancreatitis". Gastroenterology. 139 (1): 140–8, quiz e12–3. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2010.03.054. PMID 20353791.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Nagpal, Sajan Jiv Singh; Sharma, Ayush; Chari, Suresh T. (September 2018). "Autoimmune Pancreatitis". American Journal of Gastroenterology. 113 (9): 1301. doi:10.1038/s41395-018-0146-0. PMID 29910463. S2CID 49268848.

- 1 2 Kamisawa, Terumi; Takuma, Kensuke; Egawa, Naoto; Tsuruta, Koji; Sasaki, Tsuneo (July 2010). "Autoimmune pancreatitis and IgG4-related sclerosing disease". Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 7 (7): 401–409. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2010.81. PMID 20548323. S2CID 3039273.

- ↑ Frulloni, Lucca; Lunardi, Claudio; Simone, Rita; Scattolini, Chiara; Falconi, Massimo; Benini, Luigi; Vantini, Italo; Corrocher, Roberto; Puccetti, Antonio (November 2009). "Identification of a novel antibody associated with autoimmune pancreatitis". New England Journal of Medicine. 361 (22): 2135–42. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0903068. PMID 19940298.

- ↑ Buijs, Jorie; Cahen, Djuna; van Heerde, Marianne; Hansen, Bettina; van Buuren, Henk; Peppelenbosch, Maikel; Fuhler, Gwenny; Bruno, Marco (November 2016). "Testing for Anti-PBP Antibody Is Not Useful in Diagnosing Autoimmune Pancreatitis". American Journal of Gastroenterology. 111 (11): 1650–54. doi:10.1038/ajg.2016.241. PMID 27325222. S2CID 21363945.

- 1 2 Khandelwal, Ashish; Shanbhogue, Alampady Krishna; Takahashi, Naoki; Sandrasegaran, Kumaresan; Prasad, Srinivasa R. (2014). "Recent Advances in the Diagnosis and Management of Autoimmune Pancreatitis". American Journal of Roentgenology. 202 (5): 1007–21. doi:10.2214/AJR.13.11247. PMID 24758653.

- ↑ Okazaki, Kazuichi; Uchida, Kazushige; Matsushita, Mitsunobu; Takaoka, Makoto (2007). "How to diagnose autoimmune pancreatitis by the revised Japanese clinical criteria". Journal of Gastroenterology. 42 Suppl 18: 32–8. doi:10.1007/s00535-007-2049-5. PMID 17520221. S2CID 24338875.

- ↑ O'Reilly, Derek A; Malde, Deep J; Duncan, Trish; Rao, Madhu; Filobbos, Rafik (2014). "Review of the diagnosis, classification and management of autoimmune pancreatitis". World Journal of Gastrointestinal Pathophysiology. 5 (2): 71–81. doi:10.4291/wjgp.v5.i2.71. PMC 4025075. PMID 24891978.

- ↑ Lin, Lien-Fu; Huang, Pi-Teh; Ho, Ka-Sic; Tung, Jai-Nien (2008). "Autoimmune Chronic Pancreatitis". Journal of the Chinese Medical Association. 71 (1): 14–22. doi:10.1016/S1726-4901(08)70067-4. PMID 18218555. S2CID 23254447.

- 1 2 Law, R.; Bronner, M.; Vogt, D.; Stevens, T. (2009). "Autoimmune pancreatitis: A mimic of pancreatic cancer". Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 76 (10): 607–15. doi:10.3949/ccjm.76a.09039. PMID 19797461.

- ↑ Hart, Phil; Chari, Suresh (2013). "Immunomodulators and Rituximab in the Management of Autoimmune Pancreatitis". Pancreapedia. doi:10.3998/panc.2013.20.

- ↑ Chari, Suresh T.; Smyrk, Thomas C.; Levy, Michael J.; Topazian, Mark D.; Takahashi, Naoki; Zhang, Lizhi; Clain, Jonathan E.; Pearson, Randall K.; Petersen, Bret T.; Vege, Santhi Swaroop (2006). "Diagnosis of Autoimmune Pancreatitis: The Mayo Clinic Experience". Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 4 (8): 1010–6, quiz 934. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2006.05.017. PMID 16843735.

- ↑ Okazaki, K (November 2003). "Autoimmune pancreatitis is increasing in Japan". Gastroenterology. 125 (5): 1557–8. doi:10.1016/j.gastro.2003.09.011. PMID 14628815.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|