Choking

| Choking | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Foreign body airway obstruction (FBOA)[1] | |

| |

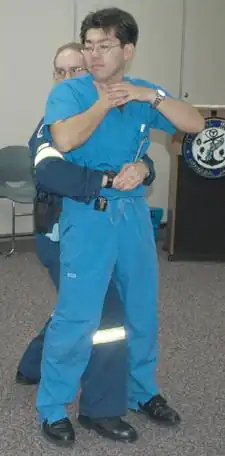

| A demonstration of abdominal thrusts on a person showing signs of choking | |

| Specialty | Emergency medicine |

| Symptoms | Drooling, coughing, wheezing, stridor, shortness of breath, holding both hands around the throat[2][3] |

| Complications | Unconsciousness[4] |

| Usual onset | Sudden[1] |

| Risk factors | Certain foods, decreased saliva production, Alzheimer, Parkinson disease[2] |

| Treatment | Mild: Encourage coughing, back slaps[4] Severe: <1 year back slaps and chest thrusts; > 1 year abdominal thrusts Unconscious: CPR, laryngoscopy[1][5] |

| Frequency | Relatively common[2] |

| Deaths | 5,000 (USA 2015)[2] |

Choking is when the airway gets blocked such that a person is unable to breathe.[4] Symptoms may include sudden onset of drooling, coughing, wheezing, stridor, shortness of breath, or holding both hands around the front of the throat.[2][3][1] People with mild choking can usually speak or cry while those with severe disease cannot.[4] Without help unconsciousness and death may occur.[4][3]

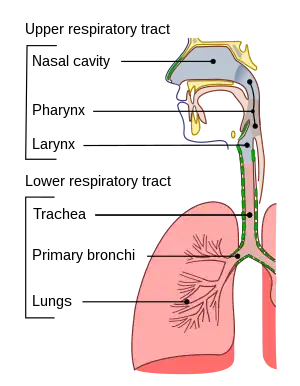

In young children it most commonly occurs due to food, toys, or a coin; while in old people it generally occurs due to food.[2] Risk factors in the elderly include decreased saliva production, Alzheimer, and Parkinson disease.[2] The underlying mechanism involves a foreign body partly or completely blocking the larynx, trachea, or bronchus.[2] Diagnosis may be supported by asking if a person is choking and them nodding their head.[3]

In those who are still able to cough, one should encourage them to do so; back slaps may be used if this is not sufficient.[4] In those who cannot cough but are still conscious; those under the age of 1 should be given 5 back slaps in a head down position followed by 5 chest thrusts; those over the age of 1 should be given abdominal thrusts.[2] In those who are unconscious CPR should be started beginning with chest compressions followed by checking the mouth for a foreign body, followed by attempts at ventilation.[1] In an unconscious person, looking with a laryngoscope and potential removal with forceps is also recommended.[5]

Choking is relatively common.[2] It most commonly occurs in 1 to 3 year old children and people over the age of 60.[2] In 2015 it resulted in around 5,000 deaths in the United States, making it the 4th leading cause of unintentional death.[2] The condition has been documented since at least 1500 BCE, with the Papyrus Ebers recommending cutting open the airway in the neck as a treatment.[6]

Signs and symptoms

The symptoms of choking include:

- Difficulty or inability to speak or cry.

- Inability to breathe or difficulty in breathing. Labored breathing, including gasping or wheezing, may be present.

- Violent and largely involuntary coughing, gurgling, or vomiting noises may be present.

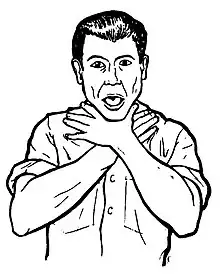

- Clutching of the throat (universal sign of choking). Maybe attempting to vomit by putting fingers down the throat.

- The face turning blue (cyanosis) from lack of oxygen if breathing is not restored.

- Falling unconscious if breathing is not restored.

Complications

The time until brain damage can vary, but typically:[7]

- Brain damage can occur when the person remains without air for approximately three minutes (it is variable).

- Death can occur if breathing is not restored in six to ten minutes (varies). However, life can be extended by using cardiopulmonary resuscitation for unconscious people.

Causes

Choking happens when a foreign body blocks the airway.[8][9] This obstruction can be located in the pharynx, the larynx, or the trachea.[10] The blockage is often partial (insufficient air passes through to the lungs), but it can be complete (when the airflow is totally blocked).[10]

Foods that pose a high risk of choking include hot dogs, hard candy, nuts, seeds, whole grapes, raw carrots, apples, popcorn, peanut butter, marshmallows, chewing gum, and sausages.[8]

Among children, the most common causes of choking are food, coins, toys, and balloons.[8] In one study, peanuts were the most common object found in the airway of children evaluated for suspected foreign body aspiration.[11] In a 1984, 29% of choking deaths in children were associated with latex balloons, making them the leading cause of choking deaths among children's products.[8] Small, round non-food objects such as balls, marbles, toys, and toy parts are also associated with a high risk of choking death because of their potential to completely block a child's airway.[8] Children younger than age three are especially at risk of choking because they explore their environment by putting objects in their mouths,[8] and they are still developing the ability to chew food completely.[8] Molar teeth, which come in around 1.5 years of age, are necessary for grinding food.[8] Even after molars are present, children continue to develop the ability to chew food completely and swallow throughout early childhood.[8] A child's airway is smaller in diameter than an adult's airway, which means that smaller objects can cause airway obstruction in children. Infants and young children generate a less-forceful cough than adults, so coughing may not be as effective in relieving airway obstruction.[8]

Risk factors of foreign body airway obstruction for people of any age include the use of alcohol or sedatives, procedures involving the oral cavity or pharynx, oral appliances, or medical conditions that cause difficulty swallowing or impair the cough reflex;[9] conditions that can cause difficulty swallowing and/or impaired coughing include neurological conditions such as strokes, Alzheimer's disease, or Parkinson's disease.[12] In older adults, risk factors also include living alone, wearing dentures, and having difficulty swallowing.[9] Children with neuromuscular disorders, developmental delay, traumatic brain injury, and other conditions that affect swallowing are at an increased risk of choking.[8] Children and adults with neurological, cognitive, or psychiatric disorders may experience a delay in diagnosis because there may not be a known history of a foreign body entering the airway.[9]

Choking on food is only one type of airway obstruction; others include blockage due to tumors, swelling of the airway tissues, and compression of the laryngopharynx, larynx, or vertebrate trachea in strangulation.

Prevention

Warning labels

According to a 1991 study, warning labels are an effective preventive measure against choking accidents. Items that contain many parts may include pieces that are considered choking hazards. Labels may state recommended age ranges (as in the case of children's toys) and warnings to parents to keep certain items out of the reach of children. Warning labels are clearly placed and written, usually including an obvious image.[13]

Dangerous foods

Choking often happens when large or abundant mouthfuls of food are poorly chewed and swallowed. This risk is minimized by cutting food into moderately sized pieces and chewing them completely before swallowing. Any food that may be chewed would have to be chewed (even the gelatinous food).

It is helpful to have some liquid available to drink to make swallowing easier. To swallow well, it is recommended that the neck be in a normal position, with the head looking forward and aligned with the eater's body, and that the eater be seated or standing rather than reclining. Some activities are not very compatible with eating (such as laughing), so eating at the same time increases the risk of choking. Food eaten by the handful (such as popcorn or nuts) requires chewing with more control than normal.

The foods that produce the worst cases of choking are those whose shapes adapt to the shape of the pharynx or trachea (such as hot dogs, sausages, bananas and food in blocks).

In 2002, candy containing konjac gel was banned by the Food and Drug Administration due to several high-profile choking cases.

Other foods are risky because they are dry in the mouth (overcooked meat, sponge cake, cold pizza), which may require drinking liquid, or eating them with purees or sauces. Tough foods are also risky (octopus, cuttlefish, reptiles or big animals), so it is recommended cutting them into smaller chunks or thinner slices, cooking them in a way that softens them, or even eating them together with something that helps the teeth to grind them (like hard bread). It is also easier to choke when eating too fast, which can usually happen in contests, games and celebrations (New Years Eve), etc.

Risk mitigation

Some population groups have a higher choking risk, such as the elderly, children, persons with disabilities (physically or mentally), people under the effects of alcohol or drugs, people who have taken medications that reduce the ability to salivate or react, patients with difficulties in swallowing (dysphagia), suicidal individuals, epileptics, and people on the autism spectrum. They may require more assistance to feed themselves, and it may be necessary to supervise them while they eat. People who are unable to chew properly should not be served hard food. In cases where a person is unable to safely eat, food can be given by feeding syringes. People who have taken any medication that reduces saliva should not eat solid food until their salivation is restored.

Children

All young children require care in eating, and they must learn to chew their food completely to avoid choking. Feeding them while they are running, playing, laughing, etc. increases the risk of choking. Caregivers must supervise children while eating or playing.[14] Pediatricians and dentists can provide information on various age groups to parents and caregivers about what food and toys are appropriate to prevent choking.[8] The American Academy of Pediatricians recommends waiting until 6 months of age before introducing solid foods to infants.[15] Caregivers should avoid giving children younger than 5 years old foods that pose a high risk of choking, such as hot dog pieces, bananas, cheese sticks, cheese chunks, hard candy, nuts, grapes, marshmallows, or popcorn.[14] Later, when they are accustomed to these foods, it is recommended to serve them split into small pieces. Some foods as hot dogs, bananas, or grapes are usually split lengthwise, sliced, or both. Parents, teachers, and other caregivers for children are advised to be trained in choking first aid and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).[8]

Children readily put small objects into their mouths (deflated balloons, marbles, small pieces, buttons, coins, button batteries, etc.), which can lead to choking. A complicated obstruction for babies is choking on deflated balloons (including preservatives) or plastic bags. This also includes the nappy sacks, used for wrapping the dirty diapers, which are sometimes dangerously placed near the babies.[16] To prevent children from swallowing things, precautions should be taken in the environment to keep dangerous objects out of their reach. Small children must be supervised closely and taught to avoid putting things into their mouths. Toys and games may indicate on their packages the ages for which they are safe. In the US, children's toy and product manufacturers are required by law to apply appropriate warning labels to their packaging,[8] but toys that are resold may not have them.[8] Caregivers can try to prevent choking by considering the features of a toy (such as size, shape, consistency and small parts) before giving it to a child.[8] Children's products that are found to pose a choking risk can be taken off the market.[8]

Treatment

Choking is treated with different procedures, which form the airway management. In a general view, this consists of the anti-choking first aid techniques, in the stage of a basic airway management, and of complex methods available as part of advanced airway management.

Basic treatment of choking includes several non-invasive techniques to help remove foreign bodies from the airways.

For a conscious person who is choking,[17] most recommend the same protocol of first-aid: asking the person to cough strongly, followed by hard back slaps and, if they are not effective, applying abdominal thrusts, or chest thrusts in case of the person can not receive pressure on the abdomen (these techniques are detailed further below).

If none of these techniques are effective, the protocols recommend alternating more series of back slaps and more series of thrusts (these on the abdomen or chest, depending of the person), in continual turns of 5 times each one ("five and five").

In addition to the people that can not receive pressure on the abdomen, other people also require specific procedures, mainly the babies and the people with disabilities.

When the choking is not being solved, it is mandatory that somebody calls for emergency medical services, and continuing the administration of first aid until they arrive.

The choking can change the colour in the person's face. After a while, they would lose consciousness and fall to the ground. Then it is recommended[18][19] avoiding panic and beginning an anti-choking cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Encouragement

If the choking person can cough it is recommended to encouraging them to stay calm and continue coughing freely.[20] Coughing with strength is very effective. Between coughs, it may be easier to take air through the nose to refill the lungs.

Back slaps

_against_choking_for_adult_people.jpg.webp)

Many associations, recommend the use of back blows (back slaps) to aid a choking person.[20][17] This technique starts by bending the choking person forward as much as possible, even trying to place their head lower than the chest, to decrease the risk that the blows drives the object deeper into the person's throat. The bending is in the back, while the neck should not be excessively bent. It is convenient that one hand supports the person's chest. Then the back blows are performed by delivering forceful slaps with the heel of the hand on the person's back, between the shoulder blades.

The back slaps push behind the blockage to expel the foreign object out. In some cases, the physical vibration of the action may cause enough movement to clear the airway.

Abdominal thrusts

Abdominal thrusts (Heimlich maneuver)[21] are performed with the rescuer standing behind the choking person. The rescuer closes the own dominant hand, grasps it with the other hand, and presses forcefully inwards and upwards with both hands on the area located between the chest and the belly button of the person. The pressure is not focused directly against the ribs to avoid breaking them. If the first thrust does not solve the choking, it can be repeated several times.

The use of abdominal thrusts is not recommended for infants under 1 year of age due to risk of causing injury, so there are adaptations for babies (see more details further below), but a child that is too big for the babies' adaptations would require normal abdominal thrusts (according to the size of the body). Besides, abdominal thrusts should not be used when the person's abdomen presents problems to receive them, such as pregnancy or excessive size; in these cases, chest thrusts are advised (see more details further below).

In the case of choking alone, abdominal thrusts are one of the possibilities that can be tried on oneself (see more details further below).

The purpose of abdominal thrusts is to create enough pressure to expel the object lodged upwards in the airway, relieving the obstruction. This method was discovered by doctor Henry Heimlich in 1974. Heimlich claimed that his maneuver was better than back blows, arguing that back blows could cause the obstruction to become more deeply lodged in the person's airway. That started a debate into the medical community,[22] that ended up with the recommendation of alternating both techniques, but making the patient to bend the back to prevent complications.[23][24][25] In addition, the patient's chest would be supported during the back slaps.

Although it is a well known method for choking intervention, the Heimlich Maneuver is backed by limited evidence and unclear guidelines. Use of the maneuver has saved many lives but can produce dire consequences if not performed correctly. This includes rib fracture, perforation of the jejunum, diaphragmatic herniation, etc.[26]

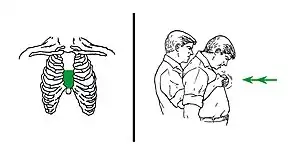

Chest thrusts

When abdominal thrusts cannot be performed on the person (because of problems as serious injuries, pregnancy or a belly size that is too much for the rescuer), chest thrusts are advised instead.[27]

Chest thrusts are performed with the rescuer standing behind the choking person. The rescuer closes the own dominant hand and grasps it with the other hand. This can produce several kinds of fists, but any of them can be valid if they can be placed on the person's chest without sinking a knuckle too painfully. Keeping the fist with both hands, the rescuer uses it to press forcefully inwards on the lower half of the chest bone (sternum). The pressure is not focused on the very endpoint (named xiphoid process) to avoid breaking it. When the person is a woman, the zone of the pressure of the chest thrusts would be normally upper than the level of the breasts. If the first thrust does not solve the choking, it can be repeated several times.

Unconscious

A choking person who becomes unconscious must be gently caught before falling and placed lying on a surface.[28] That surface should be firm enough (it is recommended placing a layer of something on the floor and laying the person above). Emergency medical services must be called, if this has not already been done.

While waiting for emergency services to arrive, the unconscious choking person should receive a cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) for choking people, that is quite similar to the CPR for any other non-breathing patient. Infants less than one year old require a special adaptation for unconscious babies of that CPR (described further below).

The anti-choking CPR[29][30] for unconscious adults or children, but not infants, is a cycle that alternates series of compressions with series of ventilations (rescue breaths). In that CPR:

Each round of compressions applies 30 compressions on the lower half of the chest bone (sternum), at an approximate rhythm of nearly 2 per second. After that series, the rescuer looks for the obstructing object and, if it is visible, the rescuer makes a try to extract it, usually by using a finger sweeping. There are no compressions during this step, but, if the removal complicates and takes a lot of time, it may require to repeat compressions at some moments, obviously without causing hindrances to the extraction. The object can be found and removed in this step or not, but this CPR procedure must continue anyway, until the people can breath by themselves or emergency medical services arrive. Next, the rescuer applies a rescue breath, pinching the person's nose and puffing air inside of the mouth. It is recommended, additionally, tilting the person's head up and down, to reposition it trying to open an entrance for the air, and then give an additional rescue breath. The rescue breaths would usually fail while the object is still inside stopping them, but then the rescuer has only to continue with the next step. Anyway, they can be successful, and then the chest of the person would rise. When a rescue breath reaches the lungs, it happens because the object has been moved to an unknown position that leaves some open space, so it can be useful making the next rescue breaths more softly to avoid moving the object to a new blocking position again, and, in case of the soft rescue breaths are not successful, increasing the strength of blowing in the next ones. The colour of the person's face would improve after several rescue breaths have been successful. After the rescue breaths, this resuscitation returns to the 30 initial compressions, in a cycle that repeats continually, until the people can breathe by themselves.

An anti-choking device can unblock the airway on unconscious people, but does not necessarily remove the obstructing object from the mouth, which may need a manual removal. The people will then require a normal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), in the manner that has been described above but only alternating the 30 compressions and the two rescue breaths.

Finger sweeping

In unconscious choking people, the American Medical Association advocates sweeping the fingers across the back of the throat to attempt to dislodge airway obstructions.[31] However, many modern protocols recommend against it. Red Cross procedures specifically direct rescuers not to perform a finger sweep unless an object can be clearly seen in the people's mouth to prevent driving the obstruction deeper into the people's airway. Other protocols suggest that if the patient is conscious they will be able to remove the foreign object themselves, or if they are unconscious, the rescuer should place them in the recovery position to allow the drainage of fluids out of the mouth instead of down the trachea due to gravity. There is also a risk of causing further damage (inducing vomiting, for instance) by using a finger sweep technique. There are no studies that have examined the usefulness of the finger sweep technique when there is no visible object in the airway. Recommendations for the use of the finger sweep have been based on anecdotal evidence.[18]

Self-treatment

Some first aid anti-choking techniques can be applied on oneself. One option is having an anti-choking device. Otherwise first aid techniques may include:

The most recommended manner consist in positioning the own abdomen over the border of an object: usually a chairback or similar and then driving the abdomen upon the border, making sharp thrusts in an inwards-an-upwards direction. It is possible to place a fist or both fists between the chosen border and the belly, to increase the pressure of the maneuver and make it easier (depending on the situation). Other variation of this consists in pressing one's own belly with an appropriated object, in an inwards-and-upwards direction.

Abdominal thrusts can also be self-applied with the hands. This is achieved by making a fist, grasping it with the other hand, and placing them on the area located between the chest and the belly button. Then the body is bent forward and the hands make strong compressions pressing in an inwards-an-upwards direction. In one study, the self-administered abdominal thrusts were rated as effective as those performed by another person.[32]

When a problem makes impossible a self treatment with abdominal thrust (as serious injuries, pregnancy, or having an excessive size of the belly for oneself), it is possible to try the self application of chest thrusts instead, despite it would be more difficult. This would be achieved by leaning the body forward, making a fist, grasping it with the other hand, and doing strong compressions inwards with both of them on the lower half of the chest bone (sternum). It is convenient to relax the chest for a better reception. Other variation of this is the use of an appropriated object to press inwards in the same point, being equally convenient to receive the compressions when the chest is relaxed.

Alternatively, multiple sources of evidence suggest that one of promising approaches for self-treatment during choking could be applying the head-down (inverse) position.[33][34][18] To make that position, it is possible to put the hands on the floor and then place the knees on an upper seat (as on a bed, a sofa, or an armchair). Some additional movements up or down can also be tried then.

Advanced

There are many advanced medical treatments to relieve choking or airway obstruction, including the removal of a foreign object with the help of a laryngoscope or bronchoscope. The use of any commercial approved anti-choking device, if it is available nearby, may be a more abrupt solution, but brief.

A cricothyrotomy may be performed as an emergency procedure when the stuck object cannot be removed. This is an intervention that involves severing a little opening in the patient's neck (between the thyroid cartilage and the cricoid cartilage, until reaching the trachea) and inserting there a tube to introduce air through it, bypassing the upper airways.[35] Usually, this procedure is only performed by someone with knowledge about it and surgical skills, when the patient is already unconscious.

Devices

There are a number of anti-choking devices, however evidence to support their use is unclear as of 2020.[36] Some are based on a mechanical vacuum effect, without a power source. Some use a direct plunger tool (LifeVac), and a vacuum syringe (Dechoker).

A 2020 systematic review of the effectiveness of the these devices found "very low certainty of evidenc", and concluded that "there are many weaknesses in the available data and few unbiased trials that test the effectiveness of anti-choking suction devices resulting in insufficient evidence to support or discourage their use."[36]

Special cases

Under 1 year

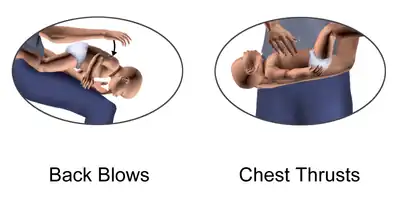

For babies (under 1 year old), the American Heart Association recommends some adapted procedures.[37] Children who are too big for the babies' procedures require the normal first aid techniques against choking, according to the size of their bodies.

First aid for babies alternates a special cycle of back blows (five back slaps) followed by chest thrusts (five adapted chest compressions). In the back blows maneuver, the rescuer slaps on the baby's back. It is recommended that the baby receive them being slightly leaned upside-down on an inclination. There exist several ways to achieve this:

In one of the most depicted, the rescuer sits down on a seat with the baby, and supports the baby with a forearm and its respective hand. The baby's head must be carefully held with that hand, usually by the jaw. Then the baby's body can be leaned forward upside-down along the rescuer's thighs and receive the slaps.

As an easier alternative, the rescuer can sit on a bed or sofa, or even the floor, carrying the baby. Next, the rescuer should support the baby's body on the own lap, to lean the baby upside-down at the right or the left of the lap. Then the slaps would be applied on the back of the baby.

If the rescuer cannot sit down, at least it is possible to attempt the maneuver at a low height and over a soft surface. Then the rescuer would support the baby with a forearm and the hand of that side, holding the baby's head with that hand, usually by the jaw. The baby's body would be leaned upside-down in that position to receive the slaps.

In the chest thrusts maneuver, the baby's body is placed lying on a surface. Then the rescuer does the compressions on the chest bone (sternum), pressing with only two fingers on its lower half (the nearest to the abdomen). Abdominal thrusts are not recommended in children less than one year old because they can cause liver damage.[38]

The back blows and chest thrusts are alternated in cycles of five back blows and five chest compressions until the object comes out of the infant's airway or until the infant becomes unconscious.[38]

When the choking is not being solved, it is mandatory that somebody calls to the emergency medical services. But the first aid has to continue until they arrive.

Unconscious

If the infant becomes unconscious, emergency medical services should be called. While they come, anti-choking cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), which must be adapted to babies is recommended.[38] In that procedure, the baby is placed face-up on a firm and horizontal surface (the floor can be used). The baby's head must be in a straight position, looking frontally, because tilting too much a baby's head backward can close the access to the trachea. Then, it is applied a cycle of resuscitation[39] that alternates compressions and rescue breaths, like in a normal CPR, but with some differences:

The rescuer makes 30 compressions with only two fingers in the lower half of the chest bone (sternum), at an approximate rhythm of nearly 2 per second. At the end of the round of compressions, the rescuer looks into the mouth for the obstructing object. And, if it is visible, the rescuer makes a try to extract it (mainly using a finger sweep). If the removal complicates and takes too much time, it may require to repeat compressions at some moments, without hindering to the extraction. A rescuer that already knows that the choking object is a bag (or similar) does not need to see the object before trying to extract it (because there is no risk of sinking it much deeper, and it is easy to detect by using the touch carefully). Being any object extracted or not, this CPR procedure must continue until the babies can breath by themselves or emergency medical services arrive. Next, the rescuer makes a rescue breath, covering the baby's mouth and nose simultaneously with the own mouth, and blowing air inside. After that first rescue breath, it is recommended tilting the baby's head up and down (but leaving it approximately straight again), trying to open a space for the air in that manner, and then give an additional rescue breath. The rescue breaths usually fail while the object is still blocking, but then the rescuer has only to continue with the next step. Anyway, they can be successful, and then the chest of the baby would be seen rising. If a rescue breath reaches the baby's lungs, it is because the object has been moved to an unknown position that leaves some open space, so it can be useful making the next rescue breaths more softly to avoid moving the object to a new blocking position again, and, in case of those soft rescue breaths are not successful, increasing the strength of blowing in the next ones. But it must be noted that the bodies of the babies are delicate, and, when the airway is not clogged, only a little strength in blowing is enough to fill their lungs. The baby's colour would improve after some successful rescue breaths. After the rescue breaths, the rescuer has to return to the 30 initial compressions, repeating the same resuscitation cycle again, continually, until the choking babies can breath normally by themselves.

Pregnancy or obesity

Some choking people cannot receive pressure on their bellies, which requires changing the abdominal thrusts for chest thrusts, as the American Heart Association recommends for them.[18]

Those people are, mainly: patients with serious injuries in the abdomen, pregnant women, and excessively obese people (with a size of belly that cannot be well managed). However, in the case of the obese people, if the rescuer is capable enough to manage the size of their bodies, it is possible to apply the normal first aid against choking, with abdominal thrusts (see details further above).

When a proper pressure on the belly is not possible, chest thrusts are preferred. Chest thrusts are performed in a similar way to the abdominal thrusts, but with the fist placed on the lower half of the chest bone (sternum), rather than over the middle of the abdomen. As a reference, in women, the zone of pressure of the chest thrusts would be normally higher than the breasts. It is convenient to avoid placing the knuckles too painfully. Finally, strong inward thrusts are then applied.[20]

The rest of the first aid protocol is the same, starting with asking the people to cough freely, and then, if the people cannot cough, the series of chest thrust are alternated with series of slaps on the back. Those back slaps are applied normally: bending forward the back of the people and supporting their chest with one hand.

If choking is not being solved, somebody has to call to the emergency medical services. But it is necessary to continue trying the first aid until they arrive.

The people can show a change of colour in their faces. After a while, they would lose consciousness, falling to the ground. Then it is recommended avoiding panic and starting an anti-choking CPR for unconscious people.

Poor mobility

If the choking person is a person in a wheelchair, the procedure is quite similar than in the case of the other people. The difference is in trying to apply the techniques directly, while the person is seated on the wheelchair.[40]

Coughing has to be tried first, so the person would be asked to cough freely and with strength before applying the techniques. When the person cannot cough, it is recommended alternating series of back blows and thrusts, as in other cases.[41][42]

If the choking person lays in bed, but is conscious and unable to sit up (such as in disabilities or injuries). Then the first aid would be the same, but after sitting the person on the bed's edge.

Before that, the rescuer tries that the person coughs freely and with strength. The person chocking would do it better by turning to a side. When coughing is too difficult or impossible, the rescuer would sit the person on the bed's edge, to make coughing easier or to apply the anti-choking maneuvers (these are required if the person cannot cough).

This can be achieved[43] grasping the person by the legs (behind of the knees, or by the calves or ankles) and rotating them until they are out of the bed. Next, the rescuer would sit the person up on the edge, pulling the shoulders or arms (in the forearms or wrists). Then it is possible to apply the anti-choking maneuvers[17] from behind: series of back slaps (after bending very much the back of the person chocking, and supporting the chest with one hand) and series of abdominal thrusts (sudden compressions in an in-and-up direction on the person's belly, between the chest and the belly button). When the person cannot receive abdominal thrusts (in cases as having serious injuries in the belly, pregnancy, and others), they must be changed for chest thrusts (sudden inward pressures on the lower half of the breast bone).

Epidemiology

Choking is the fourth leading cause of unintentional injury death in the United States.[44] Many episodes go unreported because they are brief and resolve without needing medical attention.[8] Of the reported events, 80% occur in children younger than 15 years, and 20% occur in children older than 15 years.[44] Choking on a foreign object resulted in 162,000 deaths (2.5 per 100,000) in 2013, compared with 140,000 deaths (2.9 per 100,000) in 1990.[45]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Berg, Marc D.; Schexnayder, Stephen M.; Chameides, Leon; Terry, Mark; Donoghue, Aaron; Hickey, Robert W.; Berg, Robert A.; Sutton, Robert M.; Hazinski, Mary Fran (2 November 2010). "Part 13: Pediatric Basic Life Support: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care". Circulation. 122 (18_suppl_3). doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.971085.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Duckett, Stephanie A.; Bartman, Marc; Roten, Ryan A. (2022). "Choking". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 1 October 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 "Part 3: Adult Basic Life Support". Circulation. 102 (suppl_1): I–22. 22 August 2000. doi:10.1161/circ.102.suppl_1.I-22. Archived from the original on 23 April 2022. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "What should I do if someone is choking?". nhs.uk. 26 June 2018. Archived from the original on 23 March 2022. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- 1 2 Gausche-Hill, Marianne (2007). The Pediatric Emergency Medicine Resource. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 699. ISBN 978-0-7637-4414-4. Archived from the original on 2022-04-23. Retrieved 2022-04-22.

- ↑ Engs, Ruth Clifford (11 January 2022). Bizarre Medicine: Unusual Treatments and Practices through the Ages. ABC-CLIO. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-4408-7125-2. Archived from the original on 23 April 2022. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ↑ "How Long Can the Brain Be without Oxygen before Brain Damage?". 2021-04-06. Archived from the original on 2021-04-06. Retrieved 2021-05-22.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Committee on Injury, Violence (2010-03-01). "Prevention of Choking Among Children". Pediatrics. 125 (3): 601–607. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-2862. ISSN 0031-4005. PMID 20176668. Archived from the original on 2019-11-16. Retrieved 2022-04-21.

- 1 2 3 4 Warshawsky, Martin (31 December 2015). "Foreign Body Aspiration". Medscape. Archived from the original on 8 April 2022. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- 1 2 Dominic Lucia; Jared Glenn (2008). CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment: Emergency Medicine. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-184061-3. Archived from the original on 2022-04-18. Retrieved 2022-04-21.

- ↑ Yadav, S. P.; Singh, J.; Aggarwal, N.; Goel, A. (September 2007). "Airway foreign bodies in children: experience of 132 cases". Singapore Medical Journal. 48 (9): 850–853. ISSN 0037-5675. PMID 17728968.

- ↑ Boyd, Michael; Chatterjee, Arjun; Chiles, Caroline; Chin, Robert (2009). "Tracheobronchial Foreign Body Aspiration in Adults". Southern Medical Journal. 102 (2): 171–174. doi:10.1097/smj.0b013e318193c9c8. PMID 19139679. S2CID 5401129.

- ↑ Langlois, Jean A. (1991-06-05). "The Impact of Specific Toy Warning Labels". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 265 (21): 2848–2850. doi:10.1001/jama.1991.03460210094036. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 2033742. Archived from the original on 2022-04-22. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- 1 2 "Choking Prevention for Babies". Safe Kids Worldwide. Archived from the original on 2018-10-31. Retrieved 2017-12-15.

- ↑ "Infant Food and Feeding". www.aap.org. Archived from the original on 2019-05-09. Retrieved 2017-12-15.

- ↑ "Campaign Against Nappy Sacks". Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents. Archived from the original on 2022-04-14. Retrieved 2022-04-21.

- 1 2 3 "Conscious Choking" (PDF). American Red Cross. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-01-31.

- 1 2 3 4 "Part 5: Adult Basic Life Support and Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Quality – ECC Guidelines". eccguidelines.heart.org. Archived from the original on 22 April 2022. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ↑ "STEP 3: Be Informed – Conscious Choking | Be Red Cross Ready". redcross.org. Archived from the original on 5 December 2017. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - 1 2 3 Mayo Clinic. "Choking: First aid". Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ↑ "First Aid Tips". Red Cross. Archived from the original on 2009-02-03.

- ↑ Mills Senn, Pamela (April 2007). Cincinnati Magazine. Emmis Communications. p. 92. Archived from the original on 2021-11-07. Retrieved 2022-04-21.

- ↑ American Red Cross. "New First Aid and CPR/AED Training Programs". Archived from the original on 2006-04-29. Retrieved 2021-11-07.

- ↑ "Choking: First aid". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 2014-01-02. Retrieved 2021-11-07.

- ↑ "Conscious Choking" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-01-31. Retrieved 2021-11-07.

- ↑ Fearing, Nicole M.; Harrison, Paul B. (2002-11-02). "Complications of the Heimlich Maneuver: Case Report and Literature Review". The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care. 53 (5): 978–979. doi:10.1097/00005373-200211000-00026. ISSN 0022-5282. PMID 12435952. Archived from the original on 2022-04-22. Retrieved 2022-04-21.

- ↑ "Choking and CPR safety talk". Oklahoma State University. Archived from the original on 2020-01-30.

- ↑ Herbert, Henry (1981). "Book review: The American Medical Association's Handbook of First Aid and Emergency Care". Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 23 (2): 74. doi:10.1097/00043764-198102000-00004. ISSN 1076-2752. Archived from the original on 2022-04-22. Retrieved 2022-04-21.

- ↑ American Red Cross. "Unconscious Choking". CPR/AED and First Aid. p. 22.

- ↑ "Instructor's Corner". americanredcross.force.com. Archived from the original on 2022-04-22. Retrieved 2020-01-19.

- ↑ American Medical Association Handbook of First Aid and Emergency Care. Random House. 2009-05-05. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-4000-0712-7.

dislodge the object.

- ↑ Pavitt MJ, Swanton LL, Hind M, et al. (12 April 2017). "Choking on a foreign body: a physiological study of the effectiveness of abdominal thrust manoeuvres to increase thoracic pressure". Thorax. 72 (6): 576–578. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-209540. PMC 5520267. PMID 28404809.

- ↑ Luczak, Artur (2019). "Effect of body position on relieve of foreign body from the airway†". AIMS Public Health. 6 (2): 154–159. doi:10.3934/publichealth.2019.2.154. ISSN 2327-8994. PMC 6606524. PMID 31297401.

- ↑ Luczak, Artur (June 2016). "Head-down self-treatment of choking". Resuscitation. 103: e13. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.02.015. ISSN 0300-9572. PMID 26923159.

- ↑ "What is a trachceostomy?". Archived from the original on 19 December 2018. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- 1 2 Dunne, Cody (2020). "A systematic review on the effectiveness of anti-choking suction devices and identification of research gaps". Resuscitation. 153: 219–226. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.02.021. PMID 32114068. S2CID 211725361. Archived from the original on 2022-04-22. Retrieved 2022-04-21. Downloadable draft. Archived 2022-04-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Wilkins, Lippincott Williams (2010-11-02). "Editorial Board". Circulation. 122 (18_suppl_3): S639. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181fdf7aa. Archived from the original on 2022-04-22. Retrieved 2022-04-21.

- 1 2 3 Wilkins, Lippincott Williams & (2010-11-02). "Editorial Board". Circulation. 122 (18 suppl 3): S639. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181fdf7aa. ISSN 0009-7322.

- ↑ American Red Cross. "Choking - Special Situations". CPR/AED and First Aid. p. 33.

- ↑ "Choking Awareness, wheelchair user" (PDF). Belfast Health and Social Care Trust. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-08-12. Retrieved 2022-04-21.

- ↑ "Conscious Choking" (PDF). American Red Cross. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-01-31.

- ↑ "Choking Awareness, wheelchair user" (PDF). Belfast Health and Social Care Trust. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-08-12. Retrieved 2022-04-21.

- ↑ "Assisting a Patient to a Sitting Position and Ambulation". Medicine LibreTexts. 2018-12-22. Archived from the original on 2021-10-07. Retrieved 2021-11-07.

- 1 2 "Injury Facts 2015 Edition" (PDF). National Safety Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ↑ GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators (17 December 2014). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

External links

| Classification |

|---|

- Choking at Curlie