Breast

| Breast | |

|---|---|

| |

| Details | |

| Artery | internal thoracic artery |

| Vein | internal thoracic vein |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | mamma (mammalis 'of the breast')[1] |

| MeSH | D001940 |

| TA98 | A16.0.02.001 |

| TA2 | 7097 |

| FMA | 9601 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The breast is one of two prominences located on the upper ventral region of a primate's torso. Both females and males develop breasts from the same embryological tissues.

In females, it serves as the mammary gland, which produces and secretes milk to feed infants.[2] Subcutaneous fat covers and envelops a network of ducts that converge on the nipple, and these tissues give the breast its size and shape. At the ends of the ducts are lobules, or clusters of alveoli, where milk is produced and stored in response to hormonal signals.[3] During pregnancy, the breast responds to a complex interaction of hormones, including estrogens, progesterone, and prolactin, that mediate the completion of its development, namely lobuloalveolar maturation, in preparation of lactation and breastfeeding.

Homo sapiens is the only life form with permanent breasts. At puberty, estrogens, in conjunction with growth hormone, cause permanent breast growth in female humans. This happens only to a much lesser extent in other primates - breast development in other primate females generally only occurs with pregnancy. Along with their major function in providing nutrition for infants, female breasts have social and sexual characteristics. Breasts have been featured in ancient and modern sculpture, art, and photography. They can figure prominently in the perception of a woman's body and sexual attractiveness. A number of cultures associate breasts with sexuality and tend to regard bare breasts in public as immodest or indecent. Breasts, especially the nipples, are an erogenous zone.

Etymology and terminology

| Look up breast in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

The English word breast derives from the Old English word brēost ('breast, bosom') from Proto-Germanic *breustam (breast), from the Proto-Indo-European base bhreus– (to swell, to sprout).[4] The breast spelling conforms to the Scottish and North English dialectal pronunciations.[5] The Merriam-Webster Dictionary states that "Middle English brest, [comes] from Old English brēost; akin to Old High German brust..., Old Irish brú [belly], [and] Russian bryukho"; the first known usage of the term was before the 12th century.[6]

A large number of colloquial terms for breasts are used in English, ranging from fairly polite terms to vulgar or slang.[7] Some vulgar slang expressions may be considered to be derogatory or sexist to women.[8]

Evolutionary development

Humans are the only mammals whose breasts become permanently enlarged after sexual maturity (known in humans as puberty). As of 2019, the reason for this evolutionary change was unknown.[9] Several hypotheses have been put forward:

A link has been proposed to processes for synthesizing the endogenous steroid hormone precursor dehydroepiandrosterone which takes place in fat rich regions of the body like the buttocks and breasts. These contributed to human brain development and played a part in increasing brain size. Breast enlargement may for this purpose may have occurred as early as Homo ergaster (1.7-1.4 MYA).[10] Other breast formation hypotheses may have then taken over as principal drivers.[11][12][13]

It has been suggested by zoologists Avishag and Amotz Zahavi that the size of the human breasts can be explained by the handicap theory of sexual dimorphism. This would see the explanation for larger breasts as them being an honest display of the women's health and ability to grow and carry them in her life. Prospective mates can then evaluate the genes of a potential mate for their ability to sustain her health even with the additional energy demanding burden she is carrying. [14] [10]

The zoologist Desmond Morris describes a sociobiological approach in his popular science book The Naked Ape. He suggests, by making comparisons with the other primates, that breasts evolved to replace swelling buttocks as a sex signal, of ovulation. He notes how humans have, relatively speaking, large penises as well as large breasts. Furthermore, early humans adopted bipedalism and face-to-face coitus. He therefore suggested enlarged sexual signals helped maintain the bond between a mated male and female even though they performed different duties and therefore were separated for lengths of time.[15][10][16]

The study The Evolution of the Human Breast (2001) proposed that the rounded shape of a woman's breast evolved to prevent the sucking infant offspring from suffocating while feeding at the teat; that is, because of the human infant's small jaw, which did not project from the face to reach the nipple, he or she might block the nostrils against the mother's breast if it were of a flatter form (cf. common chimpanzee). Theoretically, as the human jaw receded into the face, the woman's body compensated with round breasts.[17]

Ashley Montague (1965) proposed that breasts came about as an adaptation for infant feeding for a different reason as early human ancestors adopted bipedalism and the loss of body hair. Human upright stance meant infants must be carried at the hip or shoulder instead of on the back as in the apes. This gives the infant less opportunity to find the nipple or the purchase to cling on to the mother's body hair. The mobility of the nipple on a large breast in most human females gives the infant more ability to find grasp it and feed.[12]

Other suggestions include simply that permanent breasts attracted mates, that "pendulous" breasts gave infants something to cling to, or that permanent breasts shared the function of a camel's hump, to store fat as an energy reserve.[9]

Anatomy

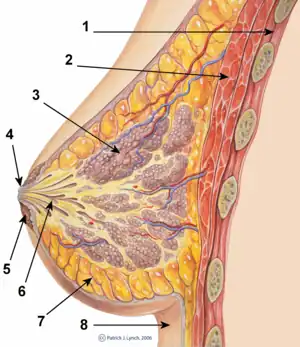

In women, the breasts overlie the pectoralis major muscles and extend on average from the level of the second rib to the level of the sixth rib in the front of the human rib cage; thus, the breasts cover much of the chest area and the chest walls. At the front of the chest, the breast tissue can extend from the clavicle (collarbone) to the middle of the sternum (breastbone). At the sides of the chest, the breast tissue can extend into the axilla (armpit), and can reach as far to the back as the latissimus dorsi muscle, extending from the lower back to the humerus bone (the bone of the upper arm). As a mammary gland, the breast is composed of differing layers of tissue, predominantly two types: adipose tissue; and glandular tissue, which affects the lactation functions of the breasts.[18]: 115

Morphologically the breast is tear-shaped.[19] The superficial tissue layer (superficial fascia) is separated from the skin by 0.5–2.5 cm of subcutaneous fat (adipose tissue). The suspensory Cooper's ligaments are fibrous-tissue prolongations that radiate from the superficial fascia to the skin envelope. The female adult breast contains 14–18 irregular lactiferous lobes that converge at the nipple. The 2.0–4.5 mm milk ducts are immediately surrounded with dense connective tissue that support the glands. Milk exits the breast through the nipple, which is surrounded by a pigmented area of skin called the areola. The size of the areola can vary widely among women. The areola contains modified sweat glands known as Montgomery's glands. These glands secrete oily fluid that lubricate and protect the nipple during breastfeeding.[20] Volatile compounds in these secretions may also serve as an olfactory stimulus for the newborn's appetite.[21]

The dimensions and weight of the breast vary widely among women. A small-to-medium-sized breast weighs 500 grams (1.1 pounds) or less, and a large breast can weigh approximately 750 to 1,000 grams (1.7 to 2.2 pounds) or more. The tissue composition ratios of the breast also vary among women. Some women's breasts have a higher proportion of glandular tissue than of adipose or connective tissues. The fat-to-connective-tissue ratio determines the density or firmness of the breast. During a woman's life, her breasts change size, shape, and weight due to hormonal changes during puberty, the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, breastfeeding, and menopause.[22][23]

Glandular structure

The breast is an apocrine gland that produces the milk used to feed an infant. The nipple of the breast is surrounded by the areola (nipple-areola complex). The areola has many sebaceous glands, and the skin color varies from pink to dark brown. The basic units of the breast are the terminal duct lobular units (TDLUs), which produce the fatty breast milk. They give the breast its offspring-feeding functions as a mammary gland. They are distributed throughout the body of the breast. Approximately two-thirds of the lactiferous tissue is within 30 mm of the base of the nipple. The terminal lactiferous ducts drain the milk from TDLUs into 4–18 lactiferous ducts, which drain to the nipple. The milk-glands-to-fat ratio is 2:1 in a lactating woman, and 1:1 in a non-lactating woman. In addition to the milk glands, the breast is also composed of connective tissues (collagen, elastin), white fat, and the suspensory Cooper's ligaments. Sensation in the breast is provided by the peripheral nervous system innervation by means of the front (anterior) and side (lateral) cutaneous branches of the fourth-, fifth-, and sixth intercostal nerves. The T-4 nerve (Thoracic spinal nerve 4), which innervates the dermatomic area, supplies sensation to the nipple-areola complex.[24]

Lymphatic drainage

Approximately 75% of the lymph from the breast travels to the axillary lymph nodes on the same side of the body, whilst 25% of the lymph travels to the parasternal nodes (beside the sternum bone).[18]: 116 A small amount of remaining lymph travels to the other breast and to the abdominal lymph nodes. The subareolar region has a lymphatic plexus known as the "subareolar plexus of Sappey".[25] The axillary lymph nodes include the pectoral (chest), subscapular (under the scapula), and humeral (humerus-bone area) lymph-node groups, which drain to the central axillary lymph nodes and to the apical axillary lymph nodes. The lymphatic drainage of the breasts is especially relevant to oncology because breast cancer is common to the mammary gland, and cancer cells can metastasize (break away) from a tumour and be dispersed to other parts of the body by means of the lymphatic system.

Shape, texture, and support

The morphologic variations in the size, shape, volume, tissue density, pectoral locale, and spacing of the breasts determine their natural shape, appearance, and position on a woman's chest. Breast size and other characteristics do not predict the fat-to-milk-gland ratio or the potential for the woman to nurse an infant. The size and the shape of the breasts are influenced by normal-life hormonal changes (thelarche, menstruation, pregnancy, menopause) and medical conditions (e.g. virginal breast hypertrophy).[26] The shape of the breasts is naturally determined by the support of the suspensory Cooper's ligaments, the underlying muscle and bone structures of the chest, and by the skin envelope. The suspensory ligaments sustain the breast from the clavicle (collarbone) and the clavico-pectoral fascia (collarbone and chest) by traversing and encompassing the fat and milk-gland tissues. The breast is positioned, affixed to, and supported upon the chest wall, while its shape is established and maintained by the skin envelope. In most women, one breast is slightly larger than the other.[19] More obvious and persistent asymmetry in breast size occurs in up to 25% of women.[27]

While it has been a common belief that breastfeeding causes breasts to sag,[28] researchers have found that a woman's breasts sag due to four key factors: cigarette smoking, number of pregnancies, gravity, and weight loss or gain.[29]

The base of each breast is attached to the chest by the deep fascia over the pectoralis major muscles. The space between the breast and the pectoralis major muscle, called retromammary space, gives mobility to the breast. The chest (thoracic cavity) progressively slopes outwards from the thoracic inlet (atop the breastbone) and above to the lowest ribs that support the breasts. The inframammary fold, where the lower portion of the breast meets the chest, is an anatomic feature created by the adherence of the breast skin and the underlying connective tissues of the chest; the IMF is the lower-most extent of the anatomic breast. Normal breast tissue typically has a texture that feels nodular or granular, to an extent that varies considerably from woman to woman.[19]

Development

The breasts are principally composed of adipose, glandular, and connective tissues.[30] Because these tissues have hormone receptors,[30][31] their sizes and volumes fluctuate according to the hormonal changes particular to thelarche (sprouting of breasts), menstruation (egg production), pregnancy (reproduction), lactation (feeding of offspring), and menopause (end of menstruation).

Puberty

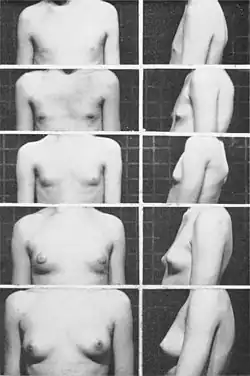

The morphological structure of the human breast is identical in males and females until puberty. For pubescent girls in thelarche (the breast-development stage), the female sex hormones (principally estrogens) in conjunction with growth hormone promote the sprouting, growth, and development of the breasts. During this time, the mammary glands grow in size and volume and begin resting on the chest. These development stages of secondary sex characteristics (breasts, pubic hair, etc.) are illustrated in the five-stage Tanner Scale.[32]

During thelarche the developing breasts are sometimes of unequal size, and usually the left breast is slightly larger. This condition of asymmetry is transitory and statistically normal in female physical and sexual development.[33] Medical conditions can cause overdevelopment (e.g., virginal breast hypertrophy, macromastia) or underdevelopment (e.g., tuberous breast deformity, micromastia) in girls and women.

Approximately two years after the onset of puberty (a girl's first menstrual cycle), estrogen and growth hormone stimulate the development and growth of the glandular fat and suspensory tissues that compose the breast. This continues for approximately four years until the final shape of the breast (size, volume, density) is established at about the age of 21. Mammoplasia (breast enlargement) in girls begins at puberty, unlike all other primates in which breasts enlarge only during lactation.[20]

Changes during the menstrual cycle

During the menstrual cycle, the breasts are enlarged by premenstrual water retention and temporary growth.[34]

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

The breasts reach full maturity only when a woman's first pregnancy occurs.[35] Changes to the breasts are among the first signs of pregnancy. The breasts become larger, the nipple-areola complex becomes larger and darker, the Montgomery's glands enlarge, and veins sometimes become more visible. Breast tenderness during pregnancy is common, especially during the first trimester. By mid-pregnancy, the breast is physiologically capable of lactation and some women can express colostrum, a form of breast milk.[36]

Pregnancy causes elevated levels of the hormone prolactin, which has a key role in the production of milk. However, milk production is blocked by the hormones progesterone and estrogen until after delivery, when progesterone and estrogen levels plummet.[37]

Menopause

At menopause, breast atrophy occurs. The breasts can decrease in size when the levels of circulating estrogen decline. The adipose tissue and milk glands also begin to wither. The breasts can also become enlarged from adverse side effects of combined oral contraceptive pills. The size of the breasts can also increase and decrease in response to weight fluctuations. Physical changes to the breasts are often recorded in the stretch marks of the skin envelope; they can serve as historical indicators of the increments and the decrements of the size and volume of a woman's breasts throughout the course of her life.

Breastfeeding

The primary function of the breasts, as mammary glands, is the nourishing of an infant with breast milk. Milk is produced in milk-secreting cells in the alveoli. When the breasts are stimulated by the suckling of her baby, the mother's brain secretes oxytocin. High levels of oxytocin trigger the contraction of muscle cells surrounding the alveoli, causing milk to flow along the ducts that connect the alveoli to the nipple.[37]

Full-term newborns have an instinct and a need to suck on a nipple, and breastfed babies nurse for both nutrition and for comfort.[38] Breast milk provides all necessary nutrients for the first six months of life, and then remains an important source of nutrition, alongside solid foods, until at least one or two years of age.

Clinical significance

The breast is susceptible to numerous benign and malignant conditions. The most frequent benign conditions are puerperal mastitis, fibrocystic breast changes and mastalgia.

Lactation unrelated to pregnancy is known as galactorrhea. It can be caused by certain drugs (such as antipsychotic medications), extreme physical stress, or endocrine disorders. Lactation in newborns is caused by hormones from the mother that crossed into the baby's bloodstream during pregnancy.

Breast cancer

Breast cancer is the most common cause of cancer death among women[39] and it is one of the leading causes of death among women. Factors that appear to be implicated in decreasing the risk of breast cancer are regular breast examinations by health care professionals, regular mammograms, self-examination of breasts, healthy diet, and exercise to decrease excess body fat,[40] and breastfeeding.[41]

Male breasts

Both females and males develop breasts from the same embryological tissues. Normally, males produce lower levels of estrogens and higher levels of androgens, namely testosterone, which suppress the effects of estrogens in developing excessive breast tissue. In boys and men, abnormal breast development is manifested as gynecomastia, the consequence of a biochemical imbalance between the normal levels of estrogen and testosterone in the male body.[42] Around 70% of boys temporarily develop breast tissue during adolescence.[27] The condition usually resolves by itself within two years.[27] When male lactation occurs, it is considered a symptom of a disorder of the pituitary gland.

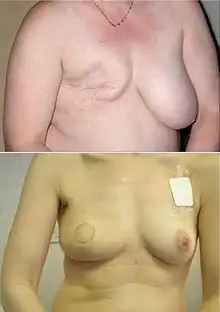

Plastic surgery

Plastic surgery can be performed to augment or reduce the size of breasts, or reconstruct the breast in cases of deformative disease, such as breast cancer.[43] Breast augmentation and breast lift (mastopexy) procedures are done only for cosmetic reasons, whereas breast reduction is sometimes medically indicated.[19] In cases where a woman's breasts are severely asymmetrical, surgery can be performed to either enlarge the smaller breast, reduce the size of the larger breast, or both.[19]

Breast augmentation surgery generally does not interfere with future ability to breastfeed.[44] Breast reduction surgery more frequently leads to decreased sensation in the nipple-areola complex, and to low milk supply in women who choose to breastfeed.[44] Implants can interfere with mammography (breast x-rays images).

Society and culture

General

In Christian iconography, some works of art depict women with their breasts in their hands or on a platter, signifying that they died as a martyr by having their breasts severed; one example of this is Saint Agatha of Sicily.[45]

Femen is a feminist activist group which uses topless protests as part of their campaigns against sex tourism[46][47] religious institutions,[48] sexism, and homophobia.[49] Femen activists have been regularly detained by police in response to their protests.[50]

There is a long history of female breasts being used by comedians as a subject for comedy fodder (e.g., British comic Benny Hill's burlesque/slapstick routines).[51]

Art history

In European pre-historic societies, sculptures of female figures with pronounced or highly exaggerated breasts were common. A typical example is the so-called Venus of Willendorf, one of many Paleolithic Venus figurines with ample hips and bosom. Artifacts such as bowls, rock carvings and sacred statues with breasts have been recorded from 15,000 BC up to late antiquity all across Europe, North Africa and the Middle East.

Many female deities representing love and fertility were associated with breasts and breast milk. Figures of the Phoenician goddess Astarte were represented as pillars studded with breasts. Isis, an Egyptian goddess who represented, among many other things, ideal motherhood, was often portrayed as suckling pharaohs, thereby confirming their divine status as rulers. Even certain male deities representing regeneration and fertility were occasionally depicted with breast-like appendices, such as the river god Hapy who was considered to be responsible for the annual overflowing of the Nile.

Female breasts were also prominent in Minoan art in the form of the famous Snake Goddess statuettes, and a few other pieces, though most female breasts are covered. In Ancient Greece there were several cults worshipping the "Kourotrophos", the suckling mother, represented by goddesses such as Gaia, Hera and Artemis. The worship of deities symbolized by the female breast in Greece became less common during the first millennium. The popular adoration of female goddesses decreased significantly during the rise of the Greek city states, a legacy which was passed on to the later Roman Empire.[52]

During the middle of the first millennium BC, Greek culture experienced a gradual change in the perception of female breasts. Women in art were covered in clothing from the neck down, including female goddesses like Athena, the patron of Athens who represented heroic endeavor. There were exceptions: Aphrodite, the goddess of love, was more frequently portrayed fully nude, though in postures that were intended to portray shyness or modesty, a portrayal that has been compared to modern pin ups by historian Marilyn Yalom.[53] Although nude men were depicted standing upright, most depictions of female nudity in Greek art occurred "usually with drapery near at hand and with a forward-bending, self-protecting posture".[54] A popular legend at the time was of the Amazons, a tribe of fierce female warriors who socialized with men only for procreation and even removed one breast to become better warriors (the idea being that the right breast would interfere with the operation of a bow and arrow). The legend was a popular motif in art during Greek and Roman antiquity and served as an antithetical cautionary tale.

.JPG.webp) A Cretan snake goddess from the Minoan civilization, c. 1600 BC

A Cretan snake goddess from the Minoan civilization, c. 1600 BC 1825 oil painting entitled Tetuppa, a Native Female of the Sandwich Islands, by Robert Dampier

1825 oil painting entitled Tetuppa, a Native Female of the Sandwich Islands, by Robert Dampier

Body image

Many women regard their breasts as important to their sexual attractiveness, as a sign of femininity that is important to their sense of self. A woman with smaller breasts may regard her breasts as less attractive.[55]

Clothing

Because breasts are mostly fatty tissue, their shape can—within limits—be molded by clothing, such as foundation garments. Bras are commonly worn by about 90% of Western women,[56][57][58] and are often worn for support.[59] The social norm in most Western cultures is to cover breasts in public, though the extent of coverage varies depending on the social context. Some religions ascribe a special status to the female breast, either in formal teachings or through symbolism.[60] Islam forbids free women from exposing their breasts in public.

Many cultures, including Western cultures in North America, associate breasts with sexuality and tend to regard bare breasts as immodest or indecent. In some cultures, like the Himba in northern Namibia, bare-breasted women are normal. In some African cultures, for example, the thigh is regarded as highly sexualised and never exposed in public, but breast exposure is not taboo. In a few Western countries and regions female toplessness at a beach is acceptable, although it may not be acceptable in the town center.

Social attitudes and laws regarding breastfeeding in public vary widely. In many countries, breastfeeding in public is common, legally protected, and generally not regarded as an issue. However, even though the practice may be legal or socially accepted, some mothers may nevertheless be reluctant to expose a breast in public to breastfeed[61][62] due to actual or potential objections by other people, negative comments, or harassment.[63] It is estimated that around 63% of mothers across the world have publicly breast-fed.[64] Bare-breasted women are legal and culturally acceptable at public beaches in Australia and much of Europe. Filmmaker Lina Esco made a film entitled Free the Nipple, which is about "...laws against female toplessness or restrictions on images of female, but not male, nipples", which Esco states is an example of sexism in society.[51]

Sexual characteristic

In some cultures, breasts play a role in human sexual activity. In Western culture, breasts have a "...hallowed sexual status, arguably more fetishized than either sex’s genitalia".[51] Breasts and especially the nipples are among the various human erogenous zones. They are sensitive to the touch as they have many nerve endings; and it is common to press or massage them with hands or orally before or during sexual activity. During sexual arousal, breast size increases, venous patterns across the breasts become more visible, and nipples harden. Compared to other primates, human breasts are proportionately large throughout adult females' lives. Some writers have suggested that they may have evolved as a visual signal of sexual maturity and fertility.[65]

Many people regard bare female breasts to be aesthetically pleasing or erotic, and they can elicit heightened sexual desires in men in many cultures. In the ancient Indian work the Kama Sutra, light scratching of the breasts with nails and biting with teeth are considered erotic.[66] Some people show a sexual interest in female breasts distinct from that of the person, which may be regarded as a breast fetish.[67] A number of Western fashions include clothing which accentuate the breasts, such as the use of push-up bras and decollete (plunging neckline) gowns and blouses which show cleavage. While U.S. culture prefers breasts that are youthful and upright, some cultures venerate women with drooping breasts, indicating mothering and the wisdom of experience.[68]

Research conducted at the Victoria University of Wellington showed that breasts are often the first thing men look at, and for a longer time than other body parts.[69] The writers of the study had initially speculated that the reason for this is due to endocrinology with larger breasts indicating higher levels of estrogen and a sign of greater fertility,[69][70] but the researchers said that "Men may be looking more often at the breasts because they are simply aesthetically pleasing, regardless of the size."[69]

Some women report achieving an orgasm from nipple stimulation, but this is rare.[71][72] Research suggests that the orgasms are genital orgasms, and may also be directly linked to "the genital area of the brain". In these cases, it seems that sensation from the nipples travels to the same part of the brain as sensations from the vagina, clitoris and cervix. Nipple stimulation may trigger uterine contractions, which then produce a sensation in the genital area of the brain.[73][74][75]

Anthropomorphic geography

There are many mountains named after the breast because they resemble it in appearance and so are objects of religious and ancestral veneration as a fertility symbol and of well-being. In Asia, there was "Breast Mountain", which had a cave where the Buddhist monk Bodhidharma (Da Mo) spent much time in meditation.[76] Other such breast mountains are Mount Elgon on the Uganda–Kenya border; Beinn Chìochan and the Maiden Paps in Scotland; the Bundok ng Susong Dalaga ('Maiden's breast mountains') in Talim Island, Philippines, the twin hills known as the Paps of Anu (Dá Chích Anann or 'the breasts of Anu'), near Killarney in Ireland; the 2,086 m high Tetica de Bacares or La Tetica in the Sierra de Los Filabres, Spain; Khao Nom Sao in Thailand, Cerro Las Tetas in Puerto Rico; and the Breasts of Aphrodite in Mykonos, among many others. In the United States, the Teton Range is named after the French word for 'nipple'.[77]

See also

Medicine portal

Medicine portal Human sexuality portal

Human sexuality portal- Udder

References

- ↑ "mammal". Dictionary.reference.com. Archived from the original on 14 November 2011. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ↑ "Breast – Definition of breast by Merriam-Webster". merriam-webster.com. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ↑ "SEER Training: Breast Anatomy". National Cancer Institute. Archived from the original on 2 May 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- ↑ "Early Indo-European Online: Introduction to the Language Lessons". www.utexas.edu. Archived from the original on 20 April 2016.

- ↑ "Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com. Archived from the original on 2 February 2012. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- ↑ "Definition of BREAST". www.merriam-webster.com. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- ↑ See wikt:Thesaurus:breasts

- ↑ Groot, Sue de. "Is there a respectful slang word for breasts?". Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 11 December 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- 1 2 https://www.discovermagazine.com/planet-earth/scientists-still-stumped-by-the-evolution-of-human-breasts

- 1 2 3 Pawłowski, Bogusław; Żelaźniewicz, Agnieszka (13 July 2021). "The evolution of perennially enlarged breasts in women: a critical review and a novel hypothesis". Biological Reviews. 96 (6): 2794–2809. doi:10.1111/brv.12778. PMID 34254729. S2CID 235807642.

- ↑ LeBlanc, Steven A.; Barnes, Ethne (July 1974). "On the Adaptive Significance of the Female Breast". The American Naturalist. 108 (962): 577–578. doi:10.1086/282935. ISSN 0003-0147. S2CID 85243414.

- 1 2 Howard, Beatrice A.; Veltmaat, Jacqueline M. (18 May 2013). "Embryonic Mammary Gland Development; a Domain of Fundamental Research with High Relevance for Breast Cancer Research". Journal of Mammary Gland Biology and Neoplasia. 18 (2): 89–91. doi:10.1007/s10911-013-9296-2. ISSN 1083-3021. PMID 23686554. S2CID 1657065.

- ↑ Pawłowski, Bogusław; Żelaźniewicz, Agnieszka (2021). "The evolution of perennially enlarged breasts in women: a critical review and a novel hypothesis". Biological Reviews. 96 (6): 2794–2809. doi:10.1111/brv.12778. ISSN 1469-185X. PMID 34254729. S2CID 235807642.

- ↑ Geoffrey Miller: The Sexual Evolution. Choice of partner and the emergence of the mind. Spectrum Academic Publishing House, 2009, ISBN 978-3-8274-2508-9 .

- ↑ "The Naked Ape at 50: 'Its central claim has surely stood the test of time '". the Guardian. 24 September 2017. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ↑ Binns, Corey (5 August 2010). "Why Do Women Have Breasts?". livescience.com. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ↑ Bentley, Gillian R. (2001). "The Evolution of the Human Breast". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 32 (38): 30–50. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1033.

- 1 2 Drake, Richard L.; Vogl, Wayne; Tibbitts, Adam W.M. Mitchell (2005). Gray's anatomy for students. illustrations by Richard Richardson, Paul. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0-8089-2306-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Love, Susan M. (2015). "1". Dr. Susan Love's Breast Book (6 ed.). U.S.A.: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-07382-1821-2.

- 1 2 Stöppler, Melissa Conrad. "Breast Anatomy". Archived from the original on 27 June 2015. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- ↑ Doucet, Sébastien; Soussignan, Robert; Sagot, Paul; Schaal, Benoist (2009). Hausberger, Martine (ed.). "The Secretion of Areolar (Montgomery's) Glands from Lactating Women Elicits Selective, Unconditional Responses in Neonates". PLOS ONE. 4 (10): e7579. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.7579D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007579. PMC 2761488. PMID 19851461.

- ↑ Pamplona DC, de Abreu Alvim C. Breast Reconstruction with Expanders and Implants: a Numerical Analysis. Artificial Organs 8 (2004), pp. 353–356.

- ↑ Grassley, JS (2002). "Breast Reduction Surgery: What every Woman Needs to Know". Lifelines. 6 (3): 244–249. doi:10.1111/j.1552-6356.2002.tb00088.x. PMID 12078570.

- ↑ Tortora, Gerard J.; Grabowski, Sandra Reynolds (2001). Introduction to the Human Body: the Essentials of Anatomy and Physiology (Fifth. ed.). New York; Toronto: J. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-36777-2.

- ↑ Pacifici, Stefano. "Sappey plexus | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org". Radiopaedia.

- ↑ Wood K, Cameron M, Fitzgerald K (2008). "Breast Size, Bra Fit and Thoracic Pain in Young Women: A Correlational Study". Chiropractic & Osteopathy. 16: 1. doi:10.1186/1746-1340-16-1. PMC 2275741. PMID 18339205.

- 1 2 3 "Breast Development". Massachusetts Hospital for Children. Archived from the original on 25 December 2010. Retrieved 2 June 2010.

- ↑ Lauersen, Niels H.; Stukane, Eileen (1998). The Complete Book of Breast Care (1st Trade Paperback ed.). New York: Fawcett Columbine/Ballantine. ISBN 978-0-449-91241-6.

...there is no medical reason to wear a bra, so the decision is yours, based on your own personal comfort and aesthetics. Whether you have always worn a bra or always gone braless, age and breastfeeding will naturally cause your breasts to sag.

- ↑ Rinker, B; Veneracion, M; Walsh, C (2008). "The Effect of Breastfeeding on Breast Aesthetics". Aesthetic Surgery Journal. 28 (5): 534–7. doi:10.1016/j.asj.2008.07.004. PMID 19083576. Archived from the original on 3 July 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2015. Lay summary – LiveScience (2 November 2007).

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|lay-source=(help) - 1 2 Robert L. Barbieri (2009), "Yen & Jaffe's Reproductive Endocrinology", Yen (6th ed.), Elsevier: 235–248, doi:10.1016/B978-1-4160-4907-4.00010-3, ISBN 978-1-4160-4907-4, archived from the original on 6 March 2018, retrieved 6 March 2018

- ↑ Brisken; Malley (2 December 2010), "Hormone Action in the Mammary Gland", Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 2 (12): a003178, doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a003178, PMC 2982168, PMID 20739412

- ↑ Greenbaum AR, Heslop T, Morris J, Dunn KW (April 2003). "An Investigation of the Suitability of Bra fit in Women Referred for Reduction Mammaplasty". British Journal of Plastic Surgery. 56 (3): 230–6. doi:10.1016/S0007-1226(03)00122-X. PMID 12859918.

- ↑ Loughry CW; et al. (1989). "Breast Volume Measurement of 598 Women using Biostereometric Analysis". Annals of Plastic Surgery. 22 (5): 380–385. doi:10.1097/00000637-198905000-00002. PMID 2729845. S2CID 8713713.

- ↑ Breast – premenstrual tenderness and swelling, A.D.A.M., May 2012, archived from the original on 5 July 2016, retrieved 21 March 2018

- ↑ Lawrence 2016, p. 34.

- ↑ Lawrence 2016, p. 58.

- 1 2 "The physiological basis of breastfeeding". NCBI Bookshelf. 5 November 2008. Archived from the original on 19 January 2018. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

- ↑ Lawrence 2016, p. 201.

- ↑ World Health Organization (February 2006). "Fact sheet No. 297: Cancer". Archived from the original on 13 February 2014. Retrieved 26 April 2007.

- ↑ Seven things you should know about breast cancer risk Archived 4 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine Harvard College. Last updated June 2008

- ↑ Stuebe, Alison M. (May 2017). "Reducing cancer risk by enabling women to breastfeed". Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers. 26 (5 Supplement): IA23. doi:10.1158/1538-7755.CARISK16-IA23. Archived from the original on 23 September 2019. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- ↑ Olson, James Stuart (2002). Bathsheba's Breast: Women, Cancer and History. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-8018-6936-5. OCLC 186453370.

- ↑ "Secondary sex characteristics". .hu-berlin.de. Archived from the original on 22 June 2013. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- 1 2 Lawrence 2016, pp. 613–616.

- ↑ "St Agatha". Catholic Online. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ↑ Femen wants to move from public exposure to political power Archived 7 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Kyiv Post (28 April 2010)

- ↑ "Ukraine's Ladies of Femen". Movements.org. 16 August 2011. Archived from the original on 14 April 2012. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ↑ Ukraine's Femen:Topless protests 'help feminist cause' Archived 12 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News (23 October 2012)

- ↑ "Topless FEMEN Protesters Drench Belgian Archbishop André-Jozef Léonard, Protest Homophobia in Catholic Church (PHOTOS)". The Huffington Post. 24 April 2013. Archived from the original on 16 April 2015. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ↑ Femen activists jailed in Tunisia for topless protest Archived 27 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News (12 June 2013)

- 1 2 3 Shire, Emily (9 September 2014). "Women, It's Time to Reclaim Our Breasts". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 1 November 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ↑ Yalom (1998) pp. 9–16; see Eva Keuls (1993), Reign of the Phallus: Sexual Politics in Ancient Athens for a detailed study of male-dominant rule in ancient Greece.

- ↑ Yalom (1998), p. 18.

- ↑ Hollander (1993), p. 6.

- ↑ Koff, E., Benavage, A. Breast Size Perception and Satisfaction, Body Image, and Psychological Functioning in Caucasian and Asian American College Women. Sex Roles 38, 655–673 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018802928210

- ↑ "Bra Cup Sizes—getting fitted with the right size". 1stbras.com. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- ↑ "The Right Bra". Liv.com. Archived from the original on 28 March 2009. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- ↑ "Breast supporting act: a century of the bra". London: The Independent UK. 15 August 2007. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- ↑ Wood, K; Cameron, M; Fitzgerald, K (2008). "Breast size, bra fit and thoracic pain in young women: a correlational study". Chiropr Osteopat. 16: 1. doi:10.1186/1746-1340-16-1. PMC 2275741. PMID 18339205.

- ↑ Bohidar, Anannya (27 October 2015). "Worshipping Breasts in the Maternal Landscape of India". South Asian Studies. 31 (2015): 247–253. doi:10.1080/02666030.2015.1094209. S2CID 194282633. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ↑ Wolf, J.H. (2008). "Got milk? Not in public!". International Breastfeeding Journal. 3 (1): 11. doi:10.1186/1746-4358-3-11. PMC 2518137. PMID 18680578.

- ↑ Vance, Melissa R. (June–July 2005). "Breastfeeding Legislation in the United States: A General Overview and Implications for Helping Mothers". LEAVEN. 41 (3): 51–54. Archived from the original on 31 March 2007.

- ↑ Jordan, Tim; Pile, Steve, eds. (2002). Social Change. Blackwell. p. 233. ISBN 9780631233114.

- ↑ Cox, Sue (2002). Breast Feeding With Confidence. United States: Meadowbrook Press. ISBN 0684040050.

- ↑ Anders Pape Møller; et al. (1995). "Breast asymmetry, sexual selection, and human reproductive success". Ethology and Sociobiology. 16 (3): 207–219. doi:10.1016/0162-3095(95)00002-3.

- ↑ "Sir Richard Burton's English translation of Kama Sutra". Sacred-texts.com. Archived from the original on 2 January 2010. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ↑ Hickey, Eric W. (2003). Encyclopaedia of Murder and Violent Crime. Sage Publications Inc. ISBN 978-0-7619-2437-1

- ↑ Burns-Ardolino, Wendy (2007). Jiggle: (Re)shaping American women. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-7391-1299-1.

- 1 2 3 Dixson, BJ; Grimshaw, GM; Linklater, WL; Dixson, AF (February 2011). "Eye-tracking of men's preferences for waist-to-hip ratio and breast size of women". Archives of Sexual Behavior. International Academy of Sex Research. 40 (1): 43–50. doi:10.1007/s10508-009-9523-5. PMID 19688590. S2CID 4997497.

- ↑ "Hourglass figure fertility link". BBC News. 4 May 2004. Archived from the original on 11 October 2011. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ↑ Alfred C. Kinsey; Wardell B. Pomeroy; Clyde E. Martin; Paul H. Gebhard (1998). Sexual Behavior in the Human Female. Indiana University Press. p. 587. ISBN 0-253-01924-9. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

There are some females who appear to find no erotic satisfaction in having their breasts manipulated; perhaps half of them derive some distinct satisfaction, but not more than a very small percentage ever respond intensely enough to reach orgasm as a result of such stimulation (Chapter 5). [...] Records of females reaching orgasm from breast stimulation alone are rare.

- ↑ Boston Women's Health Book Collective (1996). The New Our Bodies, Ourselves: A Book by and for Women. Simon & Schuster. p. 575. ISBN 0-684-82352-7. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

A few women can even experience orgasm from breast stimulation alone.

- ↑ Merril D. Smith (2014). Cultural Encyclopedia of the Breast. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-7591-2332-8. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- ↑ Justin J. Lehmiller (2013). The Psychology of Human Sexuality. John Wiley & Sons. p. 120. ISBN 978-1-118-35132-1. Archived from the original on 23 February 2019. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- ↑ Komisaruk, B. R.; Wise, N.; Frangos, E.; Liu, W.C.; Allen, K.; Brody, S. (2011). "Women's Clitoris, Vagina, and Cervix Mapped on the Sensory Cortex: fMRI Evidence, Surprise finding in response to nipple stimulation". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 8 (10): 2822–30. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02388.x. PMC 3186818. PMID 21797981. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 12 August 2017. Lay summary – CBSnews.com (5 August 2011).

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|lay-source=(help) - ↑ "The Story of Bodhidharma". Usashaolintemple.org. Archived from the original on 30 November 2011. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ↑ "Creation of the Teton Landscape: The Geologic Story of Grand Teton National Park (The Story Begins)". National Park Service. 19 January 2007. Archived from the original on 19 April 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

Bibliography

- Hollander, Anne (1993). Seeing through clothes. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-08231-1.

- Morris, Desmond The Naked Ape: a zoologist's study of the human animal Bantam Books, Canada. 1967

- Yalom, Marilyn (1998). A history of the breast. London: Pandora. ISBN 978-0-86358-400-8.

- Venes, Donald (2013). Taber's cyclopedic medical dictionary. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis. ISBN 978-0-8036-2977-6.

- Lawrence, Ruth (2016). Breastfeeding : a guide for the medical profession, 8th edition. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-35776-0.

External links

| Look up breasts in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Breasts. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Breast |

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Radiation Oncology/Breast |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- "Are Women Evolutionary Sex Objects?: Why Women Have Breasts". Archived from the original on 2 December 2011.