COACH syndrome

| COACH syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Oligophrenia, Ataxia congenital, Coloboma, and Hepatic fibrosis, Joubert syndrome with congenital hepatic fibrosis, Cerebellar vermis hypoplasia-oligophrenia-congenital ataxia-coloboma-hepatic fibrosis | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

| Frequency | Lua error in Module:PrevalenceData at line 5: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). |

COACH syndrome, also known as Joubert syndrome with hepatic defect,[1] is a rare autosomal recessive genetic disease. The name is an acronym of the defining signs: cerebellar vermis aplasia, oligophrenia, congenital ataxia, coloboma and hepatic fibrosis. The condition is associated with moderate intellectual disability.[2] It falls under the category of a Joubart Syndrome-related disorder (JSRD).[3]

The syndrome was first described in 1974 by Alasdair Hunter and his peers at the Montreal Children's Hospital.[4] It was not until 1989 that it was labelled COACH syndrome, by Verloes and Lambotte, at the Sart Tilman University Hospital, Belgium.[5]

Signs and symptoms

Signs of COACH syndrome tend to present from birth to early childhood. Facial abnormalities are a common symptom, with some characteristics being broadness of the forehead, ptosis of either one or both eyes and misalignment of the eyes.[6] Other cases also report a "carp" shaped mouth, flattened face and nose and hypertelorism.[5]

Patients are often within the lower percentiles for height and weight growth.[3] Hypotonia is a possible sign of COACH syndrome.[3] Infants suffering from COACH syndrome may experience very categorical hyperventilation and complications with respiration, such as irregular breathing. It has been reported that as patients surpass infancy, these respiratory issues may disappear.[7]

Behavioral and intellectual delays are symptoms caused by the hypoplasia of the cerebellar vermis and oligophrenia.[8][9] This implies delayed onset of speech and walking, along with learning and social issues.[4] Poor motor skills and balance, speech impairment, mild gait or hand ataxia and irregular eye movement are symptoms of the disease attributed to congential ataxia.[10]

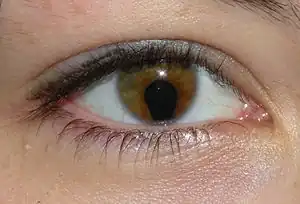

Coloboma of the eye is visible in the retina as "hole" in its structure, and causes low vision, possible sensitivity to light and variance in size of the eyeball.[11][12] The build-up of tissue in the liver, known as hepatic fibrosis, may cause symptoms such as jaundice, ascites, abnormal bleeding and enlarged spleen.[13] Kidney complications in the form of polycystic kidney or nephronophthisis is estimated to affect 77% of patients suffering from COACH syndrome, and is therefore a highly significant symptom of the disease.[6]

Genetics

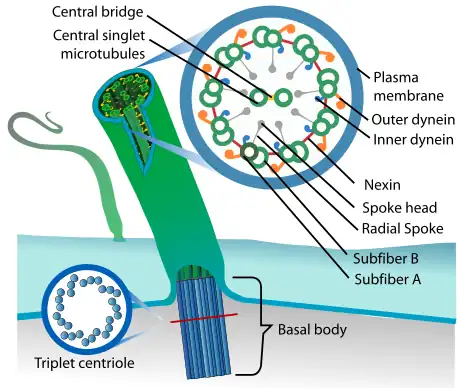

Due to generational familial linkage and the frequency of siblings sharing inheritance of COACH syndrome, it is classified as an autosomal recessive disorder. COACH syndrome is a ciliopathy, a group of diseases categorized by irregular behavior of the primary cilia, which are involved in cell division, transportation, communication and tissue differentiation. This leads to irregular tissue growth in organs and various other diseases.[6] 83% of COACH syndrome carriers presented with either one or two mutations on the MKS3 gene, and findings suggest this is where most of the symptoms can be accredited. CC2D2A and RPGRIP1L genes may also have some minor contributions, with around 8.7% reporting a mutation on the CC2D2A gene and 4.3% on the RPGRIP1L gene. These three genetic mutations reportedly cover 96% of families suffering from COACH syndrome.[14]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of COACH syndrome is based on the presence of all five categories; cerebellar vermis hypoplasia, oligophrenia, congenital ataxia, coloboma, and hepatic fibrosis.

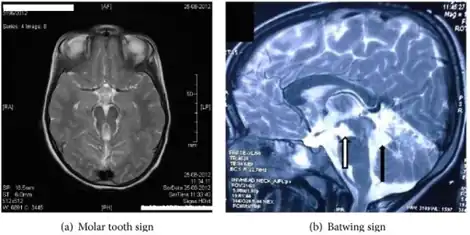

Detection of the hypoplasia of the cerebellar vermis is achieved through a cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. The presence of the ‘molar tooth sign’ (MTS) on the MRI scan, a mid- brain hind- brain malformation, confirms this condition and is a key indicator of COACH syndrome. The MTS’s distinguished shape is attributed to the lengthened superior cerebellar peduncles and deepened interpeduncular fossa.[6] To diagnose ataxia, both neurological assessment and physical examination are required. This can include MRI scans, study of behavior and motor skills in infancy and analysis of family history and genetics. In the case of congenital ataxia, patients are born with the condition and thus diagnosis is more difficult, therefore diagnosis of ataxia alone is not sufficient to indicate COACH syndrome, and must be used in conjunction with other symptoms.[15] Oligophrenia, more commonly known as intellectual disability, is diagnosed using personalized testing to measure intelligence and physical examination for anomalies and facial dysmorphia.[16] Hepatic fibrosis has a range of diagnostic techniques, including invasive and non- invasive. Liver biopsy examination is an invasive technique, which uses liver tissue extracted from the patient to identify the degree and severity of the fibrosis, and may also provide insight on tumor growth. Ultrasonography- based tests use radiation waves to measure the stiffness of the tissue and are non- invasive. Serum tests are also non- invasive, and diagnose liver complications on the basis of the amount and presence of certain proteins and chemicals in the body.[17] Kidney cysts can be discovered using ultrasound techniques, and monitoring of the patient's urine concentrating ability for any abnormalities can indicate other renal complications such as nephronophthisis.[6][7]

Management

There is no cure for COACH, syndrome, therefore treatment targets the various complications it implies and management of the disease and its symptoms.

Management includes monitoring patients’ neurological activity, development patterns and renal and hepatic function annually. Programs for special education and occupational therapy for speech and motor impairment can improve symptoms of intellectual disability and quality of life for patients. Families and patients are offered ongoing psychological support and specialized care is provided to aid societal integration. In some cases, antiepileptic drugs or neuroleptics are prescribed to reduce anger and behavioral difficulties and improve mood.[16] Some children with hypotonia and other motor skill complications may need a nasogastric feeding tube in order to ensure adequate nutrients are received and breathing is undisrupted.[6]

Ophthalmological surgery may be used to treat coloboma and ptosis of the eye to improve vision and appearance. A common technique to treat coloboma is intraocular lens (IOL) implantation, whereby a lens is surgically inserted and adhered to the iris to improve vision and appearance. In some severe cases, in conjunction with the IOL implantation, an artificial iris may be inserted into the lens capsule to treat this condition.[18] To treat ptosis, upper eyelid blepharoplasty is used for both cosmetic and functional reasons. Excess muscle and fat is removed, and the lid is raised in this procedure, and it is considered a minor procedure.[19]

If kidney function is abnormal, dialysis is a viable method of management, though is not a cure. Dialysis involves the refiltering of the blood through an external dialyzer, and is done usually three times a week to improve quality of life.[20] In most advanced cases, a kidney transplant will be required in order to ensure patient survival.[6] Hepatic fibrosis has a variety of treatment options, including anti-fibrotic methods, which aim to prevent the build-up of tissue in the liver. There are multiple methods, such as the targeting or clearance of collagen- generating cells, deactivation of receptors to certain cytokines and inhibition of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF). In cases of advanced fibrosis causing liver failure, liver transplant surgery is necessary to restore function.[14][17]

Prognosis

COACH syndrome is categorized as a Jobert syndrome related disorder (JSRD). Joubert syndrome affects approximately 1 in 80,000 to 1 in 100,000 live births, meaning it is a rare disease, while COACH syndrome is even more rare, with only 43 cases being reported from its discovery until 2010.[3] It is estimated to occur in less than one in one million people.[1] Due to this rarity, the prognosis of the disease is dealt with case- by- case. Survival depends on the severity of the symptoms, with most patients surviving infancy.[6] The likely causes of death with the progression of time are a kidney and hepatic failure in later stages of life.[21]

History

The first official report of COACH syndrome was published in 1974 at the Montreal Children's Hospital, identifying two siblings, a brother and sister, presenting with all 5 components of the disorder. The report summarizes the family history and provides detailed case reports on the two siblings, analyzing all health abnormalities to reach a conclusion about the condition. The siblings both presented with the symptoms of congenital hepatic fibrosis, choroidal colobomata, dysmorphic features, polycystic kidneys, encephalopathy causing mental retardation and growth problems. The report concludes that the symptoms presented by the siblings are not completely consistent with any other existing disorders, and thus prompted further research into the official classification of COACH syndrome in 1989.[4]

| Symptom | Sibling 1 | Sibling 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Mastoiditis and sinusitis | Yes | Yes |

| Dermatolglypics | No | Yes |

| Extra finger | No | Yes |

| Low hairline | No | Yes |

| Ptosis of eyes | No | Yes |

| High palate | Yes | Yes |

| 'Carp'- shaped mouth | Yes | Yes |

| Short middle 3 toes | Yes | No |

| Flat nose | No | Yes |

| Abnormal or underdeveloped ears | Yes | Yes |

| Anteverted nostrils | Yes | Yes |

| Perinatal complications | Yes | Yes |

| Pronounced forehead | Yes | Yes |

| Hypertelorism of eyes | Yes | Yes |

| Strabismus | Yes | Yes |

| Nystagmus | Yes | Yes |

| Decreased muscle | Yes | Yes |

| Slurred speech | Yes | No |

| Irregular movements | Yes | Yes |

| Ataxia | Yes | Yes |

| Intellectual deficit | Yes | Yes |

| Coloboma of the eye | Yes | Yes |

| Renal anomalities | Yes | Yes |

| Hepatic fibrosis | Yes | Yes |

The official report classifying COACH syndrome in 1989 by Verloes and Lambotte assesses the disorder in two siblings and a third unrelated child, finding very similar symptoms to the initial report in 1974. The report concludes by suggesting that more cases of the disorder need to be reported in order to refine its definition, and assigns the name COACH syndrome as an acronym for the major symptoms.[5]

References

- 1 2 "Orphanet: Joubert syndrome with hepatic defect". www.orpha.net. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- ↑ Bissonnette B, Luginbuehl I, Marciniak B, Dalens BJ (2006). "COACH Syndrome". Syndromes: Rapid Recognition and Perioperative Implications. The McGraw-Hill Companies. Archived from the original on 14 March 2021. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Weiland MD, Nowicki MJ, Jones JK, Giles HW (May 2011). "COACH syndrome: an unusual cause of neonatal cholestasis". The Journal of Pediatrics. 158 (5): 858–858.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.11.056. PMID 21237470.

- 1 2 3 Hunter AG, Rothman SJ, Hwang WS, Deckelbaum RJ (1974). "Hepatic fibrosis, polycystic kidney, colobomata and encephalopathy in siblings". Clinical Genetics. 6 (2): 82–9. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0004.1974.tb00636.x. PMID 4430157.

- 1 2 3 Verloes A, Lambotte C (February 1989). "Further delineation of a syndrome of cerebellar vermis hypo/aplasia, oligophrenia, congenital ataxia, coloboma, and hepatic fibrosis". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 32 (2): 227–32. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320320217. PMID 2929661.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Parisi MA (November 2009). "Clinical and molecular features of Joubert syndrome and related disorders". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part C, Seminars in Medical Genetics. 151C (4): 326–40. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.30229. PMC 2797758. PMID 19876931.

- 1 2 Acharyya BC, Goenka MK, Chatterjee S, Goenka U (February 2014). "Dealing with congenital hepatic fibrosis? Remember COACH syndrome". Clinical Journal of Gastroenterology. 7 (1): 48–51. doi:10.1007/s12328-013-0418-6. PMID 26183508.

- ↑ "Cerebellar Hypoplasia Information Page | National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke". www.ninds.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2021-03-10. Retrieved 2019-05-15.

- ↑ "Chapter 20: Oligophrenia (Congenital Dementia)". Soviet Law and Government. 8 (2–4): 377–392. 1969-10-01. doi:10.2753/RUP1061-194008020304377. ISSN 0038-5530.

- ↑ Fogel BL (September 2012). "Childhood cerebellar ataxia". Journal of Child Neurology. 27 (9): 1138–45. doi:10.1177/0883073812448231. PMC 3490706. PMID 22764177.

- ↑ Barzilai M, Ish-Shalom N, Lerner A, Iancu TC (April 1998). "Imaging findings in COACH syndrome". AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology. 170 (4): 1081–2. doi:10.2214/ajr.170.4.9530063. PMID 9530063.

- ↑ "Facts About Coloboma | National Eye Institute". nei.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2019-08-22. Retrieved 2019-05-15.

- ↑ "Facts About Coloboma | National Eye Institute". nei.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2019-08-22. Retrieved 2019-05-15.

- 1 2 Doherty D, Parisi MA, Finn LS, Gunay-Aygun M, Al-Mateen M, Bates D, et al. (January 2010). "Mutations in 3 genes (MKS3, CC2D2A and RPGRIP1L) cause COACH syndrome (Joubert syndrome with congenital hepatic fibrosis)". Journal of Medical Genetics. 47 (1): 8–21. doi:10.1136/jmg.2009.067249. PMC 3501959. PMID 19574260.

- ↑ Fogel BL (September 2012). "Childhood cerebellar ataxia". Journal of Child Neurology. 27 (9): 1138–45. doi:10.1177/0883073812448231. PMC 3490706. PMID 22764177.

- 1 2 Johnson CP, Walker WO, Palomo-González SA, Curry CJ (April 2006). "Mental retardation: diagnosis, management, and family support". Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care. 36 (4): 126–65. doi:10.1016/j.cppeds.2005.11.005. PMID 16564466.

- 1 2 Cheng JY, Wong GL (2017). "Advances in the diagnosis and treatment of liver fibrosis". Hepatoma Research. 3 (8): 156–69. doi:10.20517/2394-5079.2017.27.

- ↑ Li J, Li Y, Hu Z, Kong L (June 2014). "Intraocular lens implantation for patients with coloboma of the iris". Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine. 7 (6): 1595–1598. doi:10.3892/etm.2014.1615. PMC 4043619. PMID 24926350.

- ↑ Kwitko GM, Badri T, Patel BC (2019). "Blepharoplasty Ptosis Surgery". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29493921. Archived from the original on 2021-11-20. Retrieved 2021-09-28.

- ↑ "Hemodialysis | NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Archived from the original on 2021-03-07. Retrieved 2019-06-05.

- ↑ Brancati F, Dallapiccola B, Valente EM (July 2010). "Joubert Syndrome and related disorders". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 5 (1): 20. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-5-20. PMC 2913941. PMID 20615230.