Cerebral circulation

| Cerebral circulation | |

|---|---|

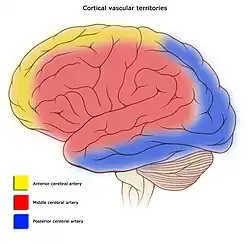

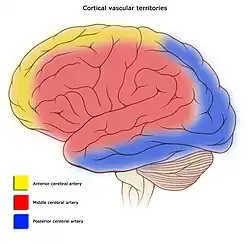

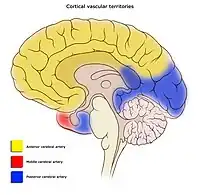

Areas of the brain are supplied by different arteries. The major systems are divided into an anterior circulation (the anterior cerebral artery and middle cerebral artery) and a posterior circulation | |

Schematic of veins and venous spaces that drain deoxygenated blood from the brain | |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D002560 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Cerebral circulation is the movement of blood through a network of cerebral arteries and veins supplying the brain. The rate of cerebral blood flow in an adult human is typically 750 milliliters per minute, or about 15% of cardiac output. Arteries deliver oxygenated blood, glucose and other nutrients to the brain. Veins carry "used or spent" blood back to the heart, to remove carbon dioxide, lactic acid, and other metabolic products.[1] Because the brain would quickly suffer damage from any stoppage in blood supply, the cerebral circulatory system has safeguards including autoregulation of the blood vessels. The failure of these safeguards may result in a stroke. The volume of blood in circulation is called the cerebral blood flow. Sudden intense accelerations change the gravitational forces perceived by bodies and can severely impair cerebral circulation and normal functions to the point of becoming serious life-threatening conditions.

The following description is based on idealized human cerebral circulation. The pattern of circulation and its nomenclature vary between organisms.

Anatomy

Blood supply

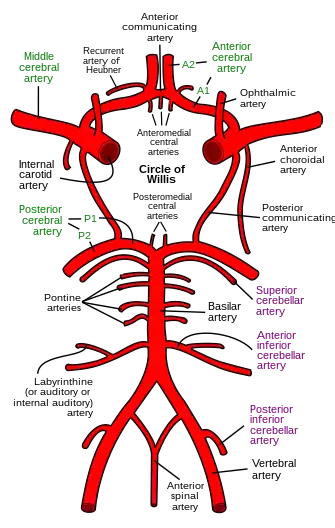

Blood supply to the brain is normally divided into anterior and posterior segments, relating to the different arteries that supply the brain. The two main pairs of arteries are the Internal carotid arteries (supply the anterior brain) and vertebral arteries (supplying the brainstem and posterior brain).[2]. The anterior and posterior cerebral circulations are interconnected via bilateral posterior communicating arteries. They are part of the Circle of Willis, which provides backup circulation to the brain. In case one of the supply arteries is occluded, the Circle of Willis provides interconnections between the anterior and the posterior cerebral circulation along the floor of the cerebral vault, providing blood to tissues that would otherwise become ischemic.[3]

Anterior cerebral circulation

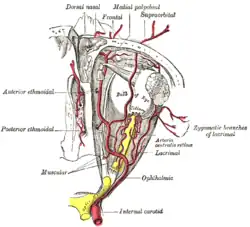

The anterior cerebral circulation is the blood supply to the anterior portion of the brain including eyes. It is supplied by the following arteries:

- Internal carotid arteries: These large arteries are the medial branches of the common carotid arteries which enter the skull, as opposed to the external carotid branches which supply the facial tissues; the internal carotid artery branches into the anterior cerebral artery and continues to form the middle cerebral artery. [4]

- Anterior cerebral artery (ACA)

- Anterior communicating artery: Connects both anterior cerebral arteries, within and along the floor of the cerebral vault.

- Middle cerebral artery (MCA)

Posterior cerebral circulation

The posterior cerebral circulation is the blood supply to the posterior portion of the brain, including the occipital lobes, cerebellum and brainstem. It is supplied by the following arteries:

- Vertebral arteries: These smaller arteries branch from the subclavian arteries which primarily supply the shoulders, lateral chest, and arms. Within the cranium the two vertebral arteries fuse into the basilar artery.

- Basilar artery: Supplies the midbrain, cerebellum, and usually branches into the posterior cerebral artery

- Posterior cerebral artery (PCA)

- Posterior communicating artery

Venous drainage

The venous drainage of the cerebrum can be separated into two subdivisions: superficial and deep.

The superficial system is composed of dural venous sinuses, which have walls composed of dura mater as opposed to a traditional vein. The dural sinuses are therefore located on the surface of the cerebrum. The most prominent of these sinuses is the superior sagittal sinus which flows in the sagittal plane under the midline of the cerebral vault, posteriorly and inferiorly to the confluence of sinuses, where the superficial drainage joins with the sinus that primarily drains the deep venous system. From here, two transverse sinuses bifurcate and travel laterally and inferiorly in an S-shaped curve that forms the sigmoid sinuses which go on to form the two jugular veins. In the neck, the jugular veins parallel the upward course of the carotid arteries and drain blood into the superior vena cava.

The deep venous drainage is primarily composed of traditional veins inside the deep structures of the brain, which join behind the midbrain to form the vein of Galen. This vein merges with the inferior sagittal sinus to form the straight sinus which then joins the superficial venous system mentioned above at the confluence of sinuses.

Physiology

Cerebral blood flow (CBF) is the blood supply to the brain in a given period of time.[5] In an adult, CBF is typically 750 millilitres per minute or 15% of the cardiac output. This equates to an average perfusion of 50 to 54 millilitres of blood per 100 grams of brain tissue per minute.[6][7][8] CBF is tightly regulated to meet the brain's metabolic demands.[6][9] Too much blood (a clinical condition of a normal homeostatic response of hyperemia)[10] can raise intracranial pressure (ICP), which can compress and damage delicate brain tissue. Too little blood flow (ischemia) results if blood flow to the brain is below 18 to 20 ml per 100 g per minute, and tissue death occurs if flow dips below 8 to 10 ml per 100 g per minute. In brain tissue, a biochemical cascade known as the ischemic cascade is triggered when the tissue becomes ischemic, potentially resulting in damage to and the death of brain cells. Medical professionals must take steps to maintain proper CBF in patients who have conditions like shock, stroke, cerebral edema, and traumatic brain injury.

Cerebral blood flow is determined by a number of factors, such as viscosity of blood, how dilated blood vessels are, and the net pressure of the flow of blood into the brain, known as cerebral perfusion pressure, which is determined by the body's blood pressure. Cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) is defined as the mean arterial pressure (MAP) minus the intracranial pressure (ICP). In normal individuals, it should be above 50 mm Hg. Intracranial pressure should not be above 15 mm Hg (ICP of 20 mm Hg is considered as intracranial hypertension). [11] Cerebral blood vessels are able to change the flow of blood through them by altering their diameters in a process called cerebral autoregulation; they constrict when systemic blood pressure is raised and dilate when it is lowered.[12] Arterioles also constrict and dilate in response to different chemical concentrations. For example, they dilate in response to higher levels of carbon dioxide in the blood and constrict in response to lower levels of carbon dioxide.[12]

For example, assuming a person with an arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2) of 40 mmHg (normal range of 38–42 mmHg)[13] and a CBF of 50 ml per 100g per min. If the PaCO2 dips to 30 mmHg, this represents a 10 mmHg decrease from the initial value of PaCO2. Consequently, the CBF decreases by 1ml per 100g per min for each 1mmHg decrease in PaCO2, resulting in a new CBF of 40ml per 100g of brain tissue per minute. In fact, for each 1 mmHg increase or decrease in PaCO2, between the range of 20–60 mmHg, there is a corresponding CBF change in the same direction of approximately 1–2 ml/100g/min, or 2–5% of the CBF value.[14] This is why small alterations in respiration pattern can cause significant changes in global CBF, specially through PaCO2 variations.[14]

CBF is equal to the cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) divided by the cerebrovascular resistance (CVR):[15]

- CBF = CPP / CVR

Control of CBF is considered in terms of the factors affecting CPP and the factors affecting CVR. CVR is controlled by four major mechanisms:

- Metabolic control (or 'metabolic autoregulation')

- Pressure autoregulation

- Chemical control (by arterial pCO2 and pO2)

- Neural control

Role of intracranial pressure

Increased intracranial pressure (ICP) causes decreased blood perfusion of brain cells by mainly two mechanisms:

- Increased ICP constitutes an increased interstitial hydrostatic pressure that, in turn, causes a decreased driving force for capillary filtration from intracerebral blood vessels.

- Increased ICP compresses cerebral arteries, causing increased cerebrovascular resistance (CVR).

Cerebral perfusion pressure

Cerebral perfusion pressure, or CPP, is the net pressure gradient causing cerebral blood flow to the brain (brain perfusion). It must be maintained within narrow limits; too little pressure could cause brain tissue to become ischemic (having inadequate blood flow), and too much could raise intracranial pressure (ICP).

Imaging

Arterial spin labeling and positron emission tomography is neuroimaging techniques that can be used to measure CBF. These techniques are also used to measure regional CBF (rCBF) within a specific brain region. rCBF at one location can be measured over time by thermal diffusion[16]

References

- ↑ Weatherspoon, Deborah, PhD., R.N., CRNA; Kinman, Tricia (16 December 2016). "Cerebral Circulation". Healthline. Healthline Media a Red Ventures Company. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- ↑ Cipolla, Marilyn J. (2009). "Anatomy and Ultrastructure". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine. Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences. Retrieved June 22, 2021.

- ↑ Chandra, Ankush; Li, William A; Stone, Christopher R; Geng, Xiaokun; Ding, Yuchuan (2017-07-17). "The cerebral circulation and cerebrovascular disease I: Anatomy". Brain Circulation. 3 (2): 45–56. doi:10.4103/bc.bc_10_17. PMC 6126264. PMID 30276305.

- ↑ "Carotid Arterial System". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 2021-06-22.

- ↑ Tolias C and Sgouros S. 2006. "Initial Evaluation and Management of CNS Injury." Archived March 2, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Emedicine.com. Accessed January 4, 2007.

- 1 2 Orlando Regional Healthcare, Education and Development. 2004. "Overview of Adult Traumatic Brain Injuries." Archived February 27, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Accessed 2008-01-16.

- ↑ Shepherd S. 2004. "Head Trauma." Emedicine.com. Shepherd S. 2004. "Head Trauma." Emedicine.com. Accessed January 4, 2007.

- ↑ Walters, FJM. 1998. "Intracranial Pressure and Cerebral Blood Flow." Archived May 14, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Physiology. Issue 8, Article 4. Accessed January 4, 2007.

- ↑ Singh J and Stock A. 2006. "Head Trauma." Emedicine.com. Accessed January 4, 2007.

- ↑ Muoio, V; Persson, PB; Sendeski, MM (April 2014). "The neurovascular unit - concept review". Acta Physiologica. 210 (4): 790–8. doi:10.1111/apha.12250. PMID 24629161. S2CID 25274791.

- ↑ Heinrich Mattle & Marco Mumenthaler with Ethan Taub (2016-12-14). Fundamentals of Neurology. Thieme. p. 129. ISBN 978-3-13-136452-4.

- 1 2 Kandel E.R., Schwartz, J.H., Jessell, T.M. 2000. Principles of Neural Science, 4th ed., McGraw-Hill, New York. p.1305

- ↑ Hadjiliadis D, Zieve D, Ogilvie I. Blood Gases. Medline Plus. 06/06/2015.

- 1 2 Giardino ND, Friedman SD, Dager SR. Anxiety, respiration, and cerebral blood flow: implications for functional brain imaging. Compr Psychiatry 2007;48:103–112. Accessed 6/6/2015.

- ↑ AnaesthesiaUK. 2007. Cerebral Blood Flow (CBF) Archived September 18, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 2007-10-16.

- ↑ P. Vajkoczy, H. Roth, P. Horn, T. Lucke, C. Thome, U. Hubner, G. T. Martin, C. Zappletal, E. Klar, L. Schilling, and P. Schmiedek, “Continuous monitoring of regional cerebral blood flow: experimental and clinical validation of a novel thermal diffusion microprobe,” J. Neurosurg., vol. 93, no. 2, pp. 265–274, Aug. 2000.