Clostridium tertium

| Clostridium tertium | |

|---|---|

| |

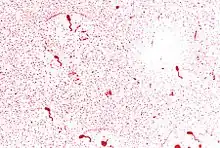

| Magnified 956X, this Gram-stained photomicrograph depicted numbers of the Gram-positive Clostridium tertium bacteria, which had been cultivated on a blood agar plate (BAP), over a time period of 48 hours. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Bacillota |

| Class: | Clostridia |

| Order: | Clostridiales |

| Family: | Clostridiaceae |

| Genus: | Clostridium |

| Species: | C. tertium |

| Binomial name | |

| Clostridium tertium (Henry 1917) Bergey et al. 1923 | |

Clostridium tertium is an anaerobic, motile, gram-positive bacterium. Although it can be considered an uncommon pathogen in humans, there has been substantial evidence of septic episodes in human beings.[1] C. tertium is easily decolorized in Gram-stained smears and can be mistaken for a Gram-negative organism.[2] However, C. tertium does not grow on selective media for Gram-negative organisms.[2]

History

Clostridium tertium was initially isolated from war wounds by Captain Herbert Henry (RAMC) in 1917, but it was not until the first human cases of C. tertium bacteremia were reported in 1963 that it was recognized as a human pathogen.[3] C. tertium has been isolated in neutropenic and nonneutropenic patients, and in cases of necrotizing fasciitis and gangrene.[4] It has also been recognized as a causative agent of enteritis in cattle, but it is an uncommon human pathogen.[4] C. tertium has also been isolated from soil and from faeces of healthy neonates and infants.[4]

Characteristics

Clostridium tertium is a Gram-positive, spore forming, anaerobic bacillus found in the soil and the gut of many animal species, including humans.[3] C. tertium distinguishes itself from other clostridia as a non-toxin producing, aerotolerant, non-histotoxic and non-lipolytic species.[3] Aerotolerant strains of anaerobic bacteria can tolerate oxygen and exhibit growth to some extent in the presence of oxygen.[5] The aerotolerance of C. tertium can lead to its misidentification as Bacillus spp. or Lactobacillus spp.[2] A negative catalase test is an easy tool to differentiate C. tertium from Bacillus spp., which are catalase positive.[2] Also, C. tertium only forms spores anaerobically, as opposed to Bacillus spp., which sporulates aerobically.[2] Other distinct characteristics are its large size (1.5 x 10 micrometers) and its unusual "square" morphology on Gram stained smear.[6]

Virulence

Clostridium tertium has traditionally been considered nonpathogenic, but increasingly it is being reported as a human pathogen.[7] The organism has been associated with bacteremia, meningitis, septic arthritis, enterocolitis, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, post-traumatic brain abscess, and pneumonia.[7] It has also been increasingly recognized as an important cause of sepsis in immunocompromised patients.[5] C. tertium has also been implicated with osteomyelitis, and miscellaneous soft tissue infections in humans.[8]

Clostridium tertium does not appear to secrete any toxin; instead, it damages gastrointestinal mucosa by direct colonization.[8] Three major factors have been associated with C. tertium bacteremia: intestinal mucosal injury, neutropenia, and history of exposure to β-lactam antibiotics (particularly third generation cephalosporins).[3] Almost all reported cases of C. tertium bacteremia have been in neutropenic patients without any obvious source of infection.[9]

It has been established that C. tertium elaborates enzymes directed against blood group A antigen in the presence of glucosamine, N-acetylglucosamine, intact blood group substance with suboptimal glucose, or completely hydrolyzed blood group substance.[10] The blood group A-splitting activity of C. tertium enzymes was inhibited by copper, zinc and nickel ions.[10]

Treatment

Clostridium tertium bacteremia can cause fever, and directed antibiotic therapy is indicated.[3] C. tertium is commonly (but not universally) resistant to many β-lactam antibiotics such as penicillin and cephalosporin; clindamycin; and metronidazole; but it is susceptible to vancomycin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and ciprofloxacin.[3] Mortality related to C. tertium bacteremia treated appropriately appears to be quite low.[3] The selection effect of antibiotics on C. tertium may occur in cases where patients have had prior exposure to β-lactam antibiotics.[3]

References

- ↑ Speirs, G; Warren (Dec 1988). "Clostridium tertium septicemia in patients with neutropenia". J Infect Dis. 158 (6): 1336–1340. doi:10.1093/infdis/158.6.1336. PMID 3198941.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Steyaert, S; Peleman, R; Vaneechoutte, M; De Baere, T; Claeys, G; Verschraegen, G (1999). "Septicemia in Neutropenic Patients with Clostridium tertium Resistant to Cefepime and Other Expanded-Spectrum Chephalosporins". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 37 (11): 3778–3779. doi:10.1128/JCM.37.11.3778-3779.1999. PMC 85761. PMID 10523601.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Miller, DL; Brazer, S; Murdoch, D; Barth Reller, L; Corey, GR (2001). "Significance of Clostridium tertium Bacteremia in Neutropenic and Nonneutropenic Patients: Review of 32 Cases". Brief Reports CID. 2001: 32. PMID 11247721.

- 1 2 3 Seol, B; Gomercic, MD; Naglic, T; Gomercic, T; Galov, A; Gomercic, H (2006). "Isolation of Clostridium tertium from a Striped Dolphin (Stenella coeruleoalba) in the Adriatic Sea". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 42 (3): 709–711. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-42.3.709. PMID 17092908. S2CID 24561452.

- 1 2 Lew, JF; Wiedermann, BL; Sneed, J; Campos, J; McCullough, D (1990). "Aerotolerant Clostridium tertium Brain Abscess following a Lawn Dart Injury". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 28 (9): 2127–2129. doi:10.1128/JCM.28.9.2127-2129.1990. PMC 268120. PMID 2229397.

- ↑ Fujitani, S; Liu, CX; Finegold, SM; Song, YL; Mathisen, GE (2007). "Clostridium tertium isolated from gas gangrene wound; misidentified as Lactobacillus spp initially due to aerotolerant feature". Anaerobe. 13 (3–4): 161–165. doi:10.1016/j.anaerobe.2007.03.002. PMID 17446094.

- 1 2 Ray, P; Das, A; Singh, K; Bhansali, A; Yadav, TD (2003). "Clostridium tertium in Necrotizing Fasciitis and Gangrene". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 9 (10): 1347–8. doi:10.3201/eid0910.030287. PMC 3033068. PMID 14626222.

- 1 2 Ferrell, ST; Tell, L (2001). "Clostridium tertium Infection in a Rainbow Lorikeet with Enteritis". Journal of Avian Medicine and Surgery. 15 (3): 204–208. doi:10.1647/1082-6742(2001)015[0204:ctiiar]2.0.co;2.

- ↑ Leegaard TM, Sandven P, Gaustad P (2005). "Clostridium tertium: 3 case reports". Scand J Infect Dis. 37 (3): 230–2. doi:10.1080/00365540410020910. PMID 15849058. S2CID 22531641.

- 1 2 Howe C., MacLennan JD, Mandl I, Kabat EA, (1957). "Enzymes of Clostridium tertium." Department of Microbiology and Neurology" Columbia University.

External links

- "Oldstyle id: 9fa31a932831ccc1bc25c0b07c53bc82". Species 2000 & ITIS Catalogue of Life. Species 2000: Naturalis, Leiden, the Netherlands.

- "Clostridium tertium" at the Encyclopedia of Life

- UniProt. "Clostridium tertium". Retrieved 2011-12-28.

- Type strain of Clostridium tertium at BacDive - the Bacterial Diversity Metadatabase