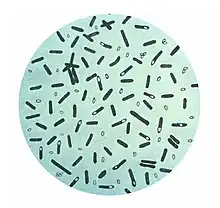

Clostridia

| Clostridia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Clostridium botulinum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Bacillota |

| Class: | Clostridia Rainey 2010 |

| Orders | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The Clostridia are a highly polyphyletic class of Firmicutes, including Clostridium and other similar genera. They are distinguished from the Bacilli by lacking aerobic respiration. They are obligate anaerobes and oxygen is toxic to them. Species of the class Clostridia are often but not always Gram-positive (see Halanaerobium hydrogenoformans) and have the ability to form spores.[1] Studies show they are not a monophyletic group, and their relationships are not entirely certain. Currently, most are placed in a single order called Clostridiales, but this is not a natural group and is likely to be redefined in the future.

Most species of the genus Clostridium are saprophytic organisms that ferment plant polysaccharides [2] and are found in many places in the environment, most notably the soil. However, the genus does contain some human pathogens (outlined below). The toxins produced by certain members of the genus Clostridium are among the most dangerous known. Examples are tetanus toxin (known as tetanospasmin) produced by C. tetani and botulinum toxin produced by C. botulinum. Some species have been isolated from women with bacterial vaginosis.[3]

Species

Notable species of this class include:

- Clostridium perfringens (gangrene, food poisoning)

- Clostridioides difficile (pseudomembranous colitis)

- Clostridium tetani (tetanus)

- Clostridium botulinum (botulism)

- Clostridium acetobutylicum (acetone–butanol–ethanol fermentation, or ABE process)

- Clostridium haemolyticum

- Clostridium novyi (gas gangrene, infectious necrotic hepatitis)

- Clostridium oedematiens (synonym of Clostridium novyi)

- Clostridium phytofermentans (biomass fermentation)

Heliobacteria and Christensenella are also members of the class Clostridia.

Some of the enzymes produced by this group are used in bioremediation.

Phylogeny

The phylogeny is based on 16S rRNA-based LTP release 132 by The All-Species Living Tree Project,[4] with the currently accepted taxonomy based on the List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN),[5] National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI)[6] and some non validated clade names from Genome Taxonomy Database.[7][8]

| Clostridia s.s. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes:

♥ Clade names not lodged at National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) or listed in the List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN)

Epidemiology

Since they are commonly found in soils and in microbiota of humans and animals, Clostridia wounds and infections are found worldwide. Host defenses against the microbe are nearly absent, and very little innate immunity exists, if any. Clostridia can be diagnosed by recognizing the characteristics of the lesion of the infection along with Gram stains of the tissue and bacterial culture.[1] Although the body does not have adequate defenses alone, this microbe can be controlled with the help of antibiotics, like penicillin, and tissue debridement for the more severe cases.

Clostridia and mental health

Clostridia bacteria are commonly found in the gut microbiome. Overuse of antibiotics can cause imbalance of the gut microbiome, leading to overgrowth of the species Clostridioides difficile causing a serious infection (CDI).[9] Effects of this infection can lead to severe diarrhea and also the increase in severity of many bowel related diseases is also increased as a results of the infection. Other Clostridia bacteria in the gut have been linked to brain connectivity and healthy function.[10]

Patients that have been subjected to fecal microbiome transplants to treat their CDI have seen improvements in their mood and mental health.[9] This preliminary research seems to suggest a tentative link between the presence of Clostridia in the gut microbiome and overall mental health, with gut microbiome transplants as an avenue of future research into novel treatments for certain psychiatric disorders.

See also

References

- 1 2 Baron, Samuel (1996). Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). Galveston: Universirt of Texas Medical Branch. ISBN 0-9631172-1-1.

- ↑ Boutard, Magali; Cerisy, Tristan; Nogue, Pierre-Yves (2014). "Functional diversity of carbohydrate-active enzymes enabling a bacterium to ferment plant biomass". PLOS Genetics. 10 (11): e1004773. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004773. PMC 4230839. PMID 25393313.

- ↑ Africa, Charlene; Nel, Janske; Stemmet, Megan (2014). "Anaerobes and Bacterial Vaginosis in Pregnancy: Virulence Factors Contributing to Vaginal Colonisation". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 11 (7): 6979–7000. doi:10.3390/ijerph110706979. ISSN 1660-4601. PMC 4113856. PMID 25014248.

- ↑ "16S rRNA-based LTP release 132 (full tree)". All-Species Living Tree Project. Silva Comprehensive Ribosomal RNA Database. Retrieved 2018-07-20.

- ↑ J.P. Euzéby. "Clostridia". List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN). Retrieved 2013-03-20.

- ↑ Sayers; et al. "Clostridia". National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) taxonomy database. Retrieved 2018-07-20.

- ↑ "GTDB taxonomy". Genome Taxonomy Database. Archived from the original on 2018-07-29. Retrieved 2018-07-20.

- ↑ Parks, D.H.; Chuvochina, M.; Waite, D.W.; Rinke, C.; Skarshewski, A.; Chaumeil, P.-A.; Hugenholtz, P. (2018). "A proposal for a standardized bacterial taxonomy based on genome phylogeny". bioRxiv: 256800. doi:10.1101/256800.

- 1 2 Jalanka, J.; Hillamaa, A.; Satokari, R.; Mattila, E.; Anttila, V.-J.; Arkkila, P. (2018). "The long-term effects of faecal microbiota transplantation for gastrointestinal symptoms and general health in patients with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 47 (3): 371–379. doi:10.1111/apt.14443. ISSN 1365-2036. PMID 29226561.

- ↑ Labus, Jennifer S.; Hsiao, Elaine; Tap, Julien; Derrien, Muriel; Gupta, Arpana; Le Nevé, Boris; Brazeilles, Rémi; Grinsvall, Cecilia; Ohman, Lena; Törnblom, Hans; Tillisch, Kirsten; Simren, Magnus; Mayer, Emeran A. (2017). "Clostridia from the Gut Microbiome are Associated with Brain Functional Connectivity and Evoked Symptoms in IBS". Gastroenterology. 152 (5): S40. doi:10.1016/S0016-5085(17)30496-1.