Body dysmorphic disorder

| Body dysmorphic disorder | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Body dysmorphia, dysmorphic syndrome, dysmorphophobia | |

| |

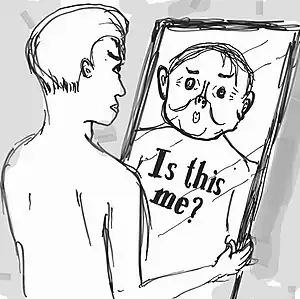

| Cartoon of person with body dysmorphia looking in mirror and seeing a distorted image of themself | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry |

| Symptoms | Preoccupation with a perceived flaw in one’s appearance that is not really noticeable by others[1] |

| Complications | Suicide[2] |

| Usual onset | Late childhood[3] |

| Duration | Long term[1] |

| Types | Muscle dysmorphia, by proxy[1] |

| Risk factors | Child abuse, family history[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Eating disorders, other obsessive-compulsive disorders, anxiety disorder, psychosis, normal concerns about appearance[1][3] |

| Treatment | Counselling, SSRIs[1] |

| Frequency | 0.7 to 2.4%[2] |

Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) is a mental disorder characterized by a preoccupation with one or more perceived flaw in one’s appearance that are not really noticeable by others.[1] This results in repeated mirror checking, efforts to cover up the defect, picking at the defect, or excessive weight lifting.[1] Generally 3 to 8 hours per day is spent on such activities and other areas of functioning are impaired.[1] Complications may include suicidal thoughts or attempts.[2]

It is believed to be due to a combination of genetic, cultural, social, and psychological factors.[1] Risk factors include child abuse and a family history of the condition.[1] It is categorized as a type of obsessive–compulsive disorder.[3] Subtype include muscle dysmorphia, in which a person feels their muscles are too small and by proxy which involves preoccupation with a perceived flaw in someone else's appearance.[1]

Cosmetic surgery does not generally improve symptoms.[2] Counselling such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or metacognitive therapy may help.[1] Medications of the SSRI type may result in improvements in 50 to 80% of people.[1] Children may drop out of school due to the condition.[3]

BDD is estimated to affect 0.7 to 2.4% of the population.[2] It usually starts during late childhood.[3] Males and females are affected at similar frequencies, though the muscle dysmorphia type generally only occurs in males.[3][1] The condition was named in 1891 by Enrico Morselli and was first included in the DSM in the IIIrd edition in 1980.[1]

Signs and symptoms

Whereas vanity involves a quest to aggrandize the appearance, BDD is experienced as a quest to merely normalize the appearance.[2] Although delusional in about one of three cases, the appearance concern is usually nondelusional, an overvalued idea.[4]

The bodily area of focus can be nearly any, yet is commonly face, hair, stomach, thighs, or hips.[5] Some half dozen areas can be a roughly simultaneous focus.[2] Many seek dermatological treatment or cosmetic surgery, which typically do not resolve the distress.[2] On the other hand, attempts at self-treatment, as by skin picking, can create lesions where none previously existed.[2]

BDD shares features with obsessive-compulsive disorder,[6] but involves more depression and social avoidance.[7] BDD often associates with social anxiety disorder.[8] Some experience delusions that others are covertly pointing out their flaws.[2] Cognitive testing and neuroimaging suggest both a bias toward detailed visual analysis and a tendency toward emotional hyper-arousal.[9]

Most generally, one experiencing BDD ruminates over the perceived bodily defect several hours daily or longer, uses either social avoidance or camouflaging with cosmetics or apparel, repetitively checks the appearance, compares it to that of other people, and might often seek verbal reassurances.[7][2] One might sometimes avoid mirrors, repetitively change outfits, groom excessively, or restrict eating.[5]

BDD's severity can wax and wane, and flareups tend to yield absences from school, work, or socializing, sometimes leading to protracted social isolation, with some becoming housebound for extended periods.[2] Social impairment is usually greatest, sometimes approaching avoidance of all social activities.[5] Poor concentration and motivation impair academic and occupational performance.[5] The distress of BDD tends to exceed that of either major depressive disorder or type-2 diabetes, and rates of suicidal ideation and attempts are especially high.[2]

Cause

As with most mental disorders, BDD's cause is likely intricate, altogether biopsychosocial, through an interaction of multiple factors, including genetic, developmental, psychological, social, and cultural.[10][11] BDD usually develops during early adolescence,[5] although many patients note earlier trauma, abuse, neglect, teasing, or bullying.[12] In many cases, social anxiety earlier in life precedes BDD. Though twin studies on BDD are few, one estimated its heritability at 43%.[13] Yet other factors may be introversion,[14] negative body image, perfectionism,[10][15] heightened aesthetic sensitivity,[11] and childhood abuse and neglect.[11][16]

Social media

Constant use of social media and “selfie taking” may translate into low self-esteem and body dysmorphic tendencies. The sociocultural theory of self-esteem states that the messages given by media and peers about the importance of appearance are internalized by individuals who adopt others’ standards of beauty as their own.[17] Due to excessive social media use and selfie taking, individuals may become preoccupied about presenting an ideal photograph for the public.

Specifically, females’ mental health has been the most affected by persistent exposure to social media. Girls with BDD present symptoms of low self-esteem and negative self-evaluation. Researchers in Istanbul Bilgi University and Bogazici University in Turkey found that individuals who have low self-esteem participate more often in trends of taking selfies along with using social media to mediate their interpersonal interaction in order to fulfill their self-esteem needs.[18] The self-verification theory, explains how individuals use selfies to gain verification from others through likes and comments. Social media may therefore trigger one’s misconception about their physical look. Similar to those with body dysmorphic tendencies, such behavior may lead to constant seeking of approval, self-evaluation and even depression.[19]

In 2019 systematic review using Web of Science, PsycINFO, and PubMed databases was used to identify social networking site patterns. In particular appearance focused social media use was found to be significantly associated with greater body image dissatisfaction. It is highlighted that comparisons appear between body image dissatisfaction and BDD symptomatology. They concluded that heavy social media use may mediate the onset of sub-threshold BDD. [20]

Individuals with BDD tend to engage in heavy plastic surgery use. Mayank Vats from Rashid Hospital in the UAE, indicated that selfies may be the reason why young people seek plastic surgery with 10% increase in nose jobs, 7% increase in hair transplants and 6% increase in eyelid surgery in 2013.[21] In 2018, the term “Snapchat Dysmorphia” was coined by Tijion Esho, a cosmetic doctor in London. The term refers to individuals seeking plastic surgeries to mimic “filtered” pictures.[22] Filtered photos, such as those on Instagram and Snapchat, often present unrealistic and unattainable looks that may be a causal factor in triggering BDD.

Diagnosis

Estimates of prevalence and gender distribution have varied widely via discrepancies in diagnosis and reporting.[7] In American psychiatry, BDD gained diagnostic criteria in the DSM-IV, but clinicians' knowledge of it, especially among general practitioners, is constricted.[23] Meanwhile, shame about having the bodily concern, and fear of the stigma of vanity, makes many hide even having the concern.[2][24]

Via shared symptoms, BDD is commonly misdiagnosed as social anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, major depressive disorder, or social phobia.[25][26] Correct diagnosis can depend on specialized questioning and correlation with emotional distress or social dysfunction.[27] Estimates place the Body Dysmorphic Disorder Questionnaire's sensitivity at 100% (0% false negatives) and specificity at 92.5% (7.5% false positives).[28]

Treatment

Anti-depressant medication, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) are considered effective.[5][29][30] SSRIs can help relieve obsessive-compulsive and delusional traits, while cognitive-behavioral therapy can help patients recognize faulty thought patterns.[5] Before treatment, it can help to provide psychoeducation, as with self-help books and support websites.[5]

History

In 1886, Enrico Morselli reported a disorder that he termed dysmorphophobia.[31] In 1980, the American Psychiatric Association recognized the disorder, while categorizing it as an atypical somatoform disorder, in the third edition of its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM).[4] Classifying it as a distinct somatoform disorder, the DSM-III 1987 revision switched the term to body dysmorphic disorder.[4]

Published in 1994, DSM-IV defines BDD as a preoccupation with an imagined or trivial defect in appearance, a preoccupation causing social or occupational dysfunction, and not better explained as another disorder, such as anorexia nervosa.[4][32] Published in 2013, the DSM-5 shifts BDD to a new category (obsessive–compulsive spectrum), adds operational criteria (such as repetitive behaviors or intrusive thoughts), and notes the subtype muscle dysmorphia (preoccupation that one's body is too small or insufficiently muscular or lean).

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Nicewicz, HR; Boutrouille, JF (January 2020). "Body Dysmorphic Disorder". PMID 32310361.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Bjornsson AS; Didie ER; Phillips KA (2010). "Body dysmorphic disorder". Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 12 (2): 221–32. PMC 3181960. PMID 20623926.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth ed.). American Psychiatric Association. 2013. pp. 242-247. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.156852. ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8.

- 1 2 3 4 Mufaddel Amir, Osman Ossama T, Almugaddam Fadwa, Jafferany Mohammad (2013). "A review of body dysmorphic disorder and Its presentation in different clinical settings". Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders. 15 (4). doi:10.4088/PCC.12r01464. PMC 3869603. PMID 24392251.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Katharine A Phillips, "Body dysmorphic disorder: Recognizing and treating imagined ugliness" Archived 2017-11-08 at the Wayback Machine, World Psychiatry, 2004 Feb;3(1):12-7.

- ↑ Fornaro M, Gabrielli F, Albano C, et al. (2009). "Obsessive-compulsive disorder and related disorders: A comprehensive survey". Annals of General Psychiatry. 8: 13. doi:10.1186/1744-859X-8-13. PMC 2686696. PMID 19450269.

- 1 2 3 Cororve, Michelle; Gleaves, David (August 2001). "Body dysmorphic disorder: A review of conceptualizations, assessment, and treatment strategies". Clinical Psychology Review. 21 (6): 949–970. doi:10.1016/s0272-7358(00)00075-1. PMID 11497214.

- ↑ Fang Angela; Hofmann Stefan G (Dec 2010). "Relationship between social anxiety disorder and body dysmorphic disorder". Clinical Psychology Review. 30 (8): 1040–1048. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2010.08.001. PMC 2952668. PMID 20817336.

- ↑ Buchanan Ben G, Rossell Susan L, Castle David J (Feb 2011). "Body dysmorphic disorder: A review of nosology, cognition and neurobiology". Neuropsychiatry. 1 (1): 71–80. doi:10.2217/npy.10.3.

- 1 2 Katharine A Phillips, Understanding Body Dysmorphic Disorder: An Essential Guide (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), ch 9. Archived 2016-05-06 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 3 Feusner, J.D.; Neziroglu, F; Wilhelm, S.; Mancusi, L.; Bohon, C. (2010). "What causes BDD: Research findings and a proposed model". Psychiatric Annals. 40 (7): 349–355. doi:10.3928/00485713-20100701-08. PMC 3859614. PMID 24347738.

- ↑ Brody, Jane E. (2010-03-22). "When your looks take over your life". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2017-10-01. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- ↑ Browne, Heidi A.; Gair, Shannon L.; Scharf, Jeremiah M.; Grice, Dorothy E. (2014-01-01). "Genetics of obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Related Disorders". Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 37 (3): 319–335. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2014.06.002. PMC 4143777. PMID 25150565.

- ↑ Veale D (2004). "Body dysmorphic disorder". British Medical Journal. 80 (940): 67–71. doi:10.1136/pmj.2003.015289. PMC 1742928. PMID 14970291.

- ↑ Hartmann, A (2014). "A comparison of self-esteem and perfectionism in anorexia nervosa and body dysmorphic disorder". Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 202 (12): 883–888. doi:10.1097/nmd.0000000000000215. PMID 25390930.

- ↑ Didie E, Tortolani C, Pope C, Menard W, Fay C, Phillips K (2006). "Childhood abuse and neglect in body dysmorphic disorder". Child Abuse and Neglect. 30 (10): 1105–1115. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.03.007. PMC 1633716. PMID 17005251.

- ↑ Exacting Beauty: Theory, Assessment, and Treatment of Body Image Disturbance.

- ↑ Varnali K. Self-disclosure on social networking sites. Social Behavior and Personality. 2015;43:1–14.doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2015.43.1.1.

- ↑ Swann WB. Self-verification: Bringing social reality into harmony with the self. In: Suls J, Greenwald AG, editors. Social psychological perspectives on the self. Vol. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1983. pp. 33–66.

- ↑ Ryding, F. C., & Kuss, D. J. (2019). The use of social networking sites, body image dissatisfaction, and body dysmorphic disorder: A systematic review of psychological research. Psychology of Popular Media Culture. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000264

- ↑ Vats M. Selfie syndrome: An infectious gift of IT to health care. J Lung Pulm Respir Res. 2015;2:48.

- ↑ "Is "Snapchat Dysmorphia" a Real Issue?". Archived from the original on 2020-09-25. Retrieved 2020-09-29.

- ↑ Katharine A Phillips. The Broken Mirror. Oxford University Press, 1996. p. 39.

- ↑ Prazeres AM, Nascimento AL, Fontenelle LF (2013). "Cognitive-behavioral therapy for body dysmorphic disorder: A review of its efficacy". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 9: 307–16. doi:10.2147/NDT.S41074. PMC 3589080. PMID 23467711.

- ↑ "Body Dysmorphic Disorder". Anxiety and Depression Association of America. Anxiety and Depression Association of America. Archived from the original on 30 January 2018. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- ↑ Katharine A Phillips. The Broken Mirror. Oxford University Press, 1996. p. 47.

- ↑ Phillips, Katherine; Castle, David (November 3, 2001). "British Medical Journal". BMJ. 323 (7320): 1015–1016. doi:10.1136/bmj.323.7320.1015. PMC 1121529. PMID 11691744.

- ↑ Grant, Jon; Won Kim, Suck; Crow, Scott (2001). "Prevalence and Clinical Features of Body Dysmorphic Disorder in Adolescent and Adult Psychiatric Inpatients". J Clin Psychiatry. 62 (7): 517–522. doi:10.4088/jcp.v62n07a03. PMID 11488361.

- ↑ Harrison, A.; Fernández de la Cruz, L.; Enander, J.; Radua, J.; Mataix-Cols, D. (2016). "Cognitive-behavioral therapy for body dysmorphic disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Clinical Psychology Review. 48: 43–51. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2016.05.007. PMID 27393916. Archived from the original on 2020-07-28. Retrieved 2019-12-20.

- ↑ Jc, Ipser; C, Sander; Dj, Stein (2009-01-21). "Pharmacotherapy and Psychotherapy for Body Dysmorphic Disorder". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005332.pub2. PMC 7159283. PMID 19160252.

- ↑ Hunt TJ; Thienhaus O; Ellwood A (July 2008). "The mirror lies: Body dysmorphic disorder". American Family Physician. 78 (2): 217–22. PMID 18697504. Archived from the original on 2021-02-24. Retrieved 2013-11-15.

- ↑ Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth text revision ed.). American Psychiatric Association, Washington DC. 2000. pp. 507–10.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |