Clubfoot

| Clubfoot | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Clubfeet, congenital talipes equinovarus (CTEV)[1] | |

.jpg.webp) | |

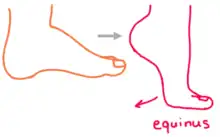

| Bilateral clubfeet | |

| Specialty | Orthopedics, podiatry |

| Symptoms | Foot that is rotated inwards and downwards[2] |

| Usual onset | During early pregnancy[1] |

| Causes | Unknown[1] |

| Risk factors | Genetics, mother who smokes cigarettes, males[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Physical examination, ultrasound during pregnancy[1][3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Metatarsus adductus[4] |

| Treatment | Ponseti method (manipulation, casting, cutting the Achilles tendon, braces), French method, surgery[1][3] |

| Prognosis | Good with proper treatment[3] |

| Frequency | 1 to 4 in 1,000[3] |

Clubfoot is a birth defect where one or both feet are rotated inward and downward.[1][2] The affected foot and leg may be smaller in size compared to the other.[1] Approximately 50% of cases of clubfoot affect both feet.[1][5] Most of the time, it is not associated with other problems.[1] Without treatment, the foot remains deformed, and people walk on the sides of their feet.[3] This may lead to pain and difficulty walking.[6]

The exact cause is usually not identified.[1][3] Both genetic and environmental factors are believed to be involved.[1][3] If one identical twin is affected, there is a 33% chance the other one will be as well.[1] The underlying mechanism involves disruption of the muscles or connective tissue of the lower leg, leading to joint contracture.[1][7] Other abnormalities are associated 20% of the time, with the most common being distal arthrogryposis and myelomeningocele.[1][3] The diagnosis may be made at birth by examination or before birth during an ultrasound exam.[1][3]

Initial treatment is most often with the Ponseti method.[1] This involves moving the foot into an improved position followed by casting, which is repeated at weekly intervals.[1] Once the inward bending is improved, the Achilles tendon is often cut, and braces are worn until the age of four.[1] Initially, the brace is worn nearly continuously and then just at night.[1] In about 20% of cases, further surgery is required.[1] Treatment can be carried out by a range of healthcare providers and can generally be achieved in the developing world with few resources.[1]

Clubfoot occurs in 1 to 4 of every 1,000 live births, making it one of the most common birth defects affecting the legs.[5][3][6] About 80% of cases occurring in developing countries where there is limited access to care.[5] Clubfoot is more common in firstborn children and males.[1][5][6] It is more common among Māori people, and less common among Chinese people.[3]

Signs and symptoms

In clubfoot, feet are rotated inward and downward.[1][2] The affected foot and leg may be smaller than the other, while in about half of cases, clubfoot affects both feet.[1][5][6] Most of the time clubfoot is not associated with other problems.[1]

Without treatment the foot remains deformed and people walk on the sides or tops of their feet, which can cause calluses, foot infections, trouble fitting into shoes, pain, difficulty walking, and disability.[6][3]

Cause

Hypotheses about the precise cause of clubfoot vary, but genetics, environmental factors or a combination of both are involved. Research has not yet pinpointed the root cause, but many findings agree that "it is likely there is more than one different cause and at least in some cases the phenotype may occur as a result of a threshold effect of different factors acting together."[8] The most commonly associated conditions are distal arthrogryposis or myelomeningocele.[3]

Some researchers hypothesize, from the early development stages of humans, that clubfoot is formed by a malfunction during gestation. Early amniocentesis (11–13 wks) is believed to increase the rate of clubfoot because there is an increase in potential amniotic leakage from the procedure. Underdevelopment of the bones and muscles of the embryonic foot may be another underlying cause. In the early 1900s, it was thought that constriction of the foot by the uterus contributed to the occurrence of clubfoot.

Underdevelopment of the bones also affects the muscles and tissues of the foot. Abnormality in the connective tissue causes "the presence of increased fibrous tissue in muscles, fascia, ligaments and tendon sheaths".[8]

Genetics

If one identical twin is affected, there is a 33% chance the other one will be as well.[1]

Mutations in genes involved in muscle development are risk factors for clubfoot, specifically those encoding the muscle contractile complex (MYH3, TPM2, TNNT3, TNNI2 and MYH8). These can cause congenital contractures, including clubfoot, in distal arthrogryposis (DA) syndromes.[9] Clubfoot can also be present in people with genetic conditions such as Loeys–Dietz syndrome and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.[10]

Genetic mapping and the development of models of the disease have improved understanding of developmental processes. Its inheritance pattern is explained as a heterogenous disorder using a polygenic threshold model. The PITX1-TBX4 transcriptional pathway has become key to the study of clubfoot. PITX1 and TBX4 are uniquely expressed in the hind limb.[11]

Diagnosis

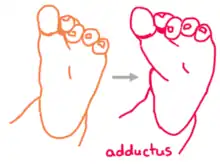

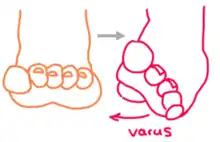

Clubfoot is diagnosed through physical examination. Typically, babies are examined from head-to-toe shortly after they are born. There are four components of the clubfoot deformity:

| 1 |  |

Cavus: the foot has a high arch, or a caved appearance. |

| 2 |  |

Adductus: the forefoot curves inwards toward the big toe. |

| 3 |  |

Varus: the heel is inverted, or turned in, forcing one to walk on the outside of the foot. This is a natural motion but in clubfoot the foot is fixed in this position. |

| 4 |  |

Equinus: the foot is pointed downward, forcing one to walk on tiptoe. This motion occurs naturally, but in clubfoot the foot is fixed in this position. This is because the Achilles tendon is tight and pulls the foot downwards. |

Factors used to assess severity include the stiffness of the deformity (how much it can be corrected by manually manipulating the foot), the presence of skin creases at the arch and heel, and poor muscle consistency.

Sometimes, it is possible to detect clubfoot before birth using ultrasound. Prenatal diagnosis by ultrasound can allow parents to learn more about this condition and plan ahead for treatment after their baby is born.[12]

More testing and imaging is typically not needed, unless there is concern for other associated conditions.

Treatment

Treatment is usually with some combination of the Ponseti method and French method.[3] The Ponseti method involves a combination of casting, Achilles tendon release, and bracing. It is widely used and highly effective under the age of two.[13] The French method involves realignment, taping, and long-term home exercises and night splinting.[3] It is also effective but outcomes vary and rely on heavy involvement of caregivers.[3] Generally, the Ponseti method is preferred.[3][14] Another technique, the Kite method, does not appear to be as effective.[14] In about 20% of cases, additional surgery is required after initial treatment.[1]

Ponseti method

The Ponseti method corrects clubfoot over the course of several stages.

- Serial casting: First, the foot is manually manipulated into an improved position and held in place with a long leg cast which extends from the toes up to the thigh. After a week this cast is removed, the foot is re-manipulated, and placed into a new cast. This process repeats and the foot is gradually reshaped over the course of 4-6 serial casts, although some feet may require additional casts.

- The goal of the initial cast is to align the forefoot with the hindfoot. Ponseti describes the forefoot as pronated in relation to the hindfoot, so supinating the forefoot and elevating the first metatarsal improves this alignment.

- Subsequent casts are applied after stretching the foot with a focus on abducting the forefoot with lateral pressure at the talus, to bring the navicular laterally and improve the alignment of the talonavicular joint. In contrast to the Kite method of casting, it is important to avoid constraining the calcanocuboid joint. With each additional cast, the abduction is increased and this moves the hindfoot from varus into valgus. It is important to leave the ankle in equinus until the forefoot and hindfoot are corrected.

- The final stage of casting, is to correct the equinus. After fully abducting the forefoot with spontaneous correction of the hindfoot, an attempt is made to bring the ankle up and into dorsiflexion.

- Achilles tendon release: At the end of the serial casting, most children have corrected cavus, adductus and varus deformities, but continue to have equinus deformity. To correct this, a procedure called an Achilles tendon release (also called Achilles tenotomy) is performed. Before the procedure, many centers place the child under sedation or monitored anesthesia care, although Ponseti recommended using local anesthetic alone. Next, the area around the heel is cleansed and numbed, and a small scalpel is used to cut the Achilles tendon. The incision is small so there is minimal bleeding and no need for stitches. The skin is covered with a small dressing, and the foot is placed into a final long leg cast in a fully corrected position. This cast is typically left in place for three weeks. During this time, the Achilles tendon will regrow in a lengthened position.

- Bracing: After successful correction is achieved through serial casting and Achilles tenotomy, the foot must be kept in a brace to prevent it from returning back to the deformed position over the first few years of a child's life. The brace is made up of two shoes or boots that are connected to each other by a bar. This device is also called a foot abduction brace (FAB). At first, the brace is worn full-time (23 hours per day) on both feet, regardless of whether the clubfoot affects one or two feet. After several months, or once the child starts pulling to stand, the brace is worn less frequently, mostly while sleeping at night and during naps. This part-time bracing phase continues until four years of age. Bracing prevents recurrence of the deformity and is a major determinant of a child's long-term outcome.[15]

The Ponseti Method is highly effective with short-term success rates of 90%.[15] However, anywhere from 14% to 41% of children experience a recurrence of the deformity.[16] The most common reason for this is inadequate adherence to bracing, such as not wearing the brace properly, not keeping it on for the recommended length of time, or not using it every day. Children who do not follow proper bracing protocol have up to 7 times higher recurrence rates than those who follow bracing protocol, as the muscles around the foot can pull it back into the abnormal position.[16] Recurrence is more common when there is poor compliance with the bracing, because the muscles around the foot can pull it back into the abnormal position. Low parental education level and failure to understand the importance of bracing is a major contributor to non-adherence.[15] Relapses are managed by repeating the casting process. Relapsed feet may also require additional, more extensive surgeries and have a reduced chance of achieving subsequent correction.[15]

Another reason for recurrence is a congenital muscle imbalance between the muscles that invert the ankle (tibialis posterior and tibialis anterior muscles) and the muscles that evert the ankle (peroneal muscles). This imbalance is present in approximately 20% of infants successfully treated with the Ponseti casting method, and makes them more prone to recurrence. After 18 months of age, this can be addressed with a surgery to transfer the tibialis anterior tendon from its medial attachment (on the navicula) to a more lateral position (on the lateral cuneiform). The surgery requires general anesthesia and subsequent casting while the tendon heals, but it is a relatively minor surgery that rebalances the muscles of the foot without disturbing any joints.

French method

The French method is a conservative, non-operative method of clubfoot treatment which involves daily physical therapy for the first two months followed by thrice-weekly physical therapy for the next four months and continued home exercises following the conclusion of formal physical therapy. During each physical therapy session the feet are manipulated, stretched, then taped to maintain any gains made to the feet's range of motion. Exercises may focus on strengthening the peroneal muscles, which is thought to contribute to long-term correction. After the two month mark, the frequency of physical therapy sessions can be weaned down to three times a week instead of daily, until the child reaches six months. After the conclusion of the physical therapy program, caregivers must continue performing exercises at home and splinting at night in order to maintain long-term correction.

Compared to the Ponseti method which uses rigid casts and braces, the French method uses tape which allows for some motion in the feet. Despite its goal to avoid surgery, the success rate varies and surgery may still be necessary. The Ponseti method is generally preferred over the French method.[3]

Surgery

If non-operative treatments are unsuccessful or achieve incomplete correction of the deformity, surgery is sometimes needed. Surgery was more common prior to the widespread acceptance of the Ponseti Method. The extent of surgery depends on the severity of the deformity. Usually, surgery is done at 9 to 12 months of age and the goal is to correct all the components of the clubfoot deformity at the time of surgery.

For feet with the typical components of deformity (cavus, forefoot adductus, hindfoot varus, and ankle equinus), the typical procedure is a Posteromedial Release (PMR) surgery. This is done through an incision across the medial side of the foot and ankle, that extends posteriorly, and sometimes around to the lateral side of the foot. In this procedure, it is typically necessary to release (cut) or lengthen the plantar fascia, several tendons, and joint capsules/ligaments. Typically, the important structures are exposed and then sequentially released until the foot can be brought to an appropriate plantigrade position. Specifically, it is important to bring the ankle to neutral, the heel into neutral, the midfoot aligned with the hindfoot (navicula aligned with the talus, and the cuboid aligned with the calcaneus). Once these joints can be aligned, thin wires are usually placed across these joints to hold them in the corrected position. These wires are temporary and left out through the skin for removal after 3–4 weeks. Once the joints are aligned, tendons (typically the Achilles, posterior tibialis, and flexor halluces longus) are repaired at an appropriate length. The incision (or incisions) are closed with dissolvable sutures. The foot is then casted in the corrected position for 6–8 weeks. It is common to do a cast change with anesthesia after 3–4 weeks, so that pins can be removed and a mold can be made to fabricate a custom AFO brace. The new cast is left in place until the AFO is available. When the cast is removed, the AFO is worn to prevent the foot from returning to the old position.[12]

For feet with partial correction of deformity with non-operative treatment, surgery may be less extensive and may involve only the posterior part of the foot and ankle. This might be called a posterior release. This is done through a smaller incision and may involve releasing only the posterior capsule of the ankle and subtalar joints, along with lengthening the Achilles tendon.

Surgery leaves residual scar tissue and typically there is more stiffness and weakness than with nonsurgical treatment. As the foot grows, there is potential for asymmetric growth that can result in recurrence of foot deformity that can affect the forefoot, midfoot, or hindfoot. Many patients do fine, but some require orthotics or additional surgeries. Long-term studies of adults with post-surgical clubfeet, especially those needing multiple surgeries, show that they may not fare as well in the long term.[17] Some people may require additional surgeries as they age, though there is some dispute as to the effectiveness of such surgeries, in light of the prevalence of scar tissue present from earlier surgeries.

Developing world

Despite effective treatments, children in LMICs face many barriers such as limited access to equipment (specifically casting materials and abduction braces), shortages of healthcare professionals, and low education levels and socioeconomic status amongst caregivers and families.[18] These factors make it difficult to detect and diagnose children with clubfoot, connect them to care, and train their caregivers to follow the proper treatment and return for follow-up visits. It is estimated that only 15% of those diagnosed with clubfoot receive treatment.[19]

In an effort to reduce the burden of clubfoot in LMICs, there have been initiatives to improve early diagnosis, organize high-volume Ponseti casting centers, utilize mid-level practitioners and non-physician health workers, engage families in care, and provide local follow-up in the person’s community.[20]

Epidemiology

Club foot occurs in 1 to 4 of every 1,000 live births.[5][6][3] It is one of the most common birth defects affecting the legs.[3] Clubfoot is more common in firstborn children and males, who are twice as likely to be affected as females.[5][6][1] It is more common among Māori people, and less common among Chinese people.[3]

Clubfoot disproportionally affects those in low and middle-income countries (LMICs). About 80% of those with clubfoot, or approximately 100,000 children per year as of 2018, are born in LMICs.[5][19]

History

Pharaohs Siptah and Tutankhamun had clubfoot, and the condition appeared in Egyptian paintings.[21] Indian texts (c. 1000 BC) and Hippocrates (c. 400 BC) described treatment.[22]

Cultural references

- The main character, Philip Carey, in W. Somerset Maugham's novel Of Human Bondage, has clubfoot, a central theme in the work.

- The main character of Alan E. Nourse's The Bladerunner has clubfoot.

- Hippolyte Tautain, the stableman at the Lion D'Or public house in Gustave Flaubert's novel Madame Bovary is unsuccessfully treated for clubfoot by Charles Bovary, leading to the eventual amputation of his leg.

- Charlie Wilcox, the main character in Sharon McKay's novel Charlie Wilcox had a clubfoot.

- In Yukio Mishima's novel The Temple of the Golden Pavilion the character Kashiwagi has clubfoot which parallels the stutter of the main character, Mizoguchi.

- In David Eddings' Malloreon series, Senji the sorcerer has a clubfoot.

- In Caroline Lawrence's Roman Mysteries series, a character called Vulcan the blacksmith appears in the book "The Secrets of Vesuvius". He reveals that he gained the nickname because of his clubfoot.

- In Bernard Cornwell's The Warlord Chronicles Mordred, King of Dumnonia, has clubfoot that is often used as a symbol for his ugliness and weakness as a ruler.

- In Daniel Keyes's Flowers for Algernon Gimpy, one of Charlie's co-workers at the bakery, has clubfoot.

- In the 1941 film High Sierra, the character Velma has clubfoot, which is successfully treated with surgery.

- In Perfume: The Story of a Murderer, the main character is born with clubfoot and is described as having a limp throughout the novel.

- In Flannery O'Connor's short story "The Lame Shall Enter First", the character Johnson has clubfoot, a major symbol of the story.

- Kwai Geuk-Chat, played by Hung Yan-yan, was the former antagonist and later new student of Wong Fei-hung in the Once Upon a Time in China franchise was nicknamed "Clubfoot Seven Chiu-Tsat" due to the shape of the disability and deformation of his feet as he is the seventh member of wealthy rival martial artist, Chiu Tin-bak's apprentices, disciples, and henchmen.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 Gibbons, PJ; Gray, K (September 2013). "Update on clubfoot". Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 49 (9): E434–7. doi:10.1111/jpc.12167. PMID 23586398.

- 1 2 3 "Talipes equinovarus". Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD). 2017. Archived from the original on 15 October 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Dobbs, Matthew B.; Gurnett, Christina A. (18 February 2009). "Update on clubfoot: etiology and treatment". Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 467 (5): 1146–1153. doi:10.1007/s11999-009-0734-9. ISSN 1528-1132. PMC 2664438. PMID 19224303.

- ↑ Moses, Scott. "Clubfoot". www.fpnotebook.com. Archived from the original on 15 October 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Smythe, Tracey; Kuper, Hannah; Macleod, David; Foster, Allen; Lavy, Christopher (March 2017). "Birth prevalence of congenital talipes equinovarus in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Tropical Medicine & International Health: TM & IH. 22 (3): 269–285. doi:10.1111/tmi.12833. ISSN 1365-3156. PMID 28000394. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2019-12-12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 O'Shea, Ryan M.; Sabatini, Coleen S. (December 2016). "What is new in idiopathic clubfoot?". Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine. 9 (4): 470–477. doi:10.1007/s12178-016-9375-2. ISSN 1935-973X. PMC 5127955. PMID 27696325.

- ↑ Cummings, R. Jay; Davidson, Richard S.; Armstrong, Peter F.; Lehman, Wallace B. (February 2002). "Congenital Clubfoot". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 84 (2): 290–308. doi:10.2106/00004623-200202000-00018. ISSN 0021-9355. PMID 11861737.

- 1 2 Miedzybrodzka, Z (January 2003). "Congenital talipes equinovarus (clubfoot): a disorder of the foot but not the hand". Journal of Anatomy. 202 (1): 37–42. doi:10.1046/j.1469-7580.2003.00147.x. PMC 1571059. PMID 12587918.

- ↑ Weymouth, KS; Blanton, SH; Bamshad, MJ; Beck, AE; Alvarez, C; Richards, S; Gurnett, CA; Dobbs, MB; Barnes, D; Mitchell, LE; Hecht, JT (September 2011). "Variants in genes that encode muscle contractile proteins influence risk for isolated clubfoot". American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 155A (9): 2170–9. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.34167. PMC 3158831. PMID 21834041.

- ↑ Byers, Peter H. (2019). Vascular Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome. University of Washington, Seattle. Archived from the original on 2021-03-08. Retrieved 2020-01-07.

- ↑ Dobbs, MB; Gurnett, CA (January 2012). "Genetics of clubfoot". Journal of Pediatric Orthopedics. Part B. 21 (1): 7–9. doi:10.1097/BPB.0b013e328349927c. PMC 3229717. PMID 21817922.

- 1 2 AskMayoExpert & et al. Can clubfoot be diagnosed in utero? Rochester, Minn.: Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research; 2012. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-07-08. Retrieved 2014-08-13.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Ganesan, B; Luximon, A; Al-Jumaily, A; Balasankar, SK; Naik, GR (2017). "Ponseti method in the management of clubfoot under 2 years of age: A systematic review". PLOS ONE. 12 (6): e0178299. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1278299G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0178299. PMC 5478104. PMID 28632733.

- 1 2 Bina, Shadi; Pacey, Verity; Barnes, Elizabeth H.; Burns, Joshua; Gray, Kelly (15 May 2020). "Interventions for congenital talipes equinovarus (clubfoot)". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 5: CD008602. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008602.pub4. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 7265154. PMID 32412098. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 Radler, Christof (September 2013). "The Ponseti method for the treatment of congenital club foot: review of the current literature and treatment recommendations". International Orthopaedics. 37 (9): 1747–1753. doi:10.1007/s00264-013-2031-1. ISSN 1432-5195. PMC 3764299. PMID 23928728.

- 1 2 Zionts, Lewis E.; Dietz, Frederick R. (August 2010). "Bracing following correction of idiopathic clubfoot using the Ponseti method". The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 18 (8): 486–493. doi:10.5435/00124635-201008000-00005. ISSN 1067-151X. PMID 20675641. S2CID 7317959.

- ↑ Dobbs, Matthew B.; Nunley, R; Schoenecker, PL (May 2006). "Long-Term Follow-up of Patients with Clubfeet Treated with Extensive Soft-Tissue Release". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 88 (5): 986–96. doi:10.2106/JBJS.E.00114. PMID 16651573. Archived from the original on 2020-07-28. Retrieved 2019-12-12.

- ↑ Owen, Rosalind; Capper, Beth; Lavy, Christopher (2018). "Clubfoot treatment in 2015: a global perspective". BMJ Global Health. 3 (4): e000852. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000852. PMC 6135438. PMID 30233830. Archived from the original on 2019-12-05. Retrieved 2019-12-05.

- 1 2 Drew, Sarah; Gooberman-Hill, Rachael; Lavy, Christopher (2 March 2018). "What factors impact on the implementation of clubfoot treatment services in low and middle-income countries?: a narrative synthesis of existing qualitative studies". BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 19 (72): 72. doi:10.1186/s12891-018-1984-z. PMC 5834880. PMID 29499667.

- ↑ Harmer, Luke; Rhatigan, Joseph (2014). "Clubfoot Care in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries: From Clinical Innovation to a Public Health Program". World Journal of Surgery. 38 (4): 839–48. doi:10.1007/s00268-013-2318-9. PMID 24213946.

- ↑ Matuszewski L, Gil L, Karski J (2012). "Early results of treatment for congenital clubfoot using the Ponseti method". Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 22 (5): 403–406. doi:10.1007/s00590-011-0860-4. PMC 3376778. PMID 22754429. Archived from the original on 2023-04-13. Retrieved 2019-10-24.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Dobbs, Matthew B; Morcuende, José A; Gurnett, Christina A; Ponseti, Ignacio V (2000). "Treatment of Idiopathic Clubfoot". The Iowa Orthopaedic Journal. 20: 59–64. ISSN 1541-5457. PMC 1888755. PMID 10934626.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |