Healthcare industry

The healthcare industry (also called the medical industry or health economy) is an aggregation and integration of sectors within the economic system that provides goods and services to treat patients with curative, preventive, rehabilitative, and palliative care. It includes the generation and commercialization of goods and services lending themselves to maintaining and re-establishing health. The modern healthcare industry includes three essential branches which are services, products, and finance and may be divided into many sectors and categories and depends on the interdisciplinary teams of trained professionals and paraprofessionals to meet health needs of individuals and populations.[1][2]

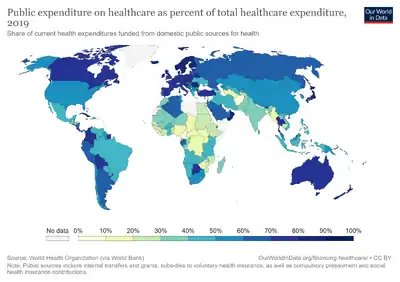

The healthcare industry is one of the world's largest and fastest-growing industries.[3] Consuming over 10 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) of most developed nations, health care can form an enormous part of a country's economy. U.S. health care spending grew 4.6 percent in 2019, reaching $3.8 trillion or $11,582 per person. As a share of the nation's Gross Domestic Product, health spending accounted for 17.7 percent.[4] The per capita expenditure on health and pharmaceuticals in OECD countries has steadily grown from a couple of hundred in the 1970s to an average of US$4'000 per year in current purchasing power parities.[5]

Backgrounds

For the purpose of finance and management, the healthcare industry is typically divided into several areas. As a basic framework for defining the sector, the United Nations International Standard Industrial Classification (ISIC) categorizes the healthcare industry as generally consisting of:

- Hospital activities;

- Medical and dental practice activities;

- "Other human health activities".

This third class involves activities of, or under the supervision of, nurses, midwives, physiotherapists, scientific or diagnostic laboratories, pathology clinics, residential health facilities, or other allied health professions, e.g. in the field of optometry, hydrotherapy, medical massage, yoga therapy, music therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, chiropody, homeopathy, chiropractic, acupuncture, etc.[6]

The Global Industry Classification Standard and the Industry Classification Benchmark further distinguish the industry as two main groups:

- healthcare equipment and services; and

- pharmaceuticals, biotechnology and related life sciences.

The healthcare equipment and services group consists of companies and entities that provide medical equipment, medical supplies, and healthcare services, such as hospitals, home healthcare providers, and nursing homes. The latter listed industry group includes companies that produce biotechnology, pharmaceuticals, and miscellaneous scientific services.[7]

Other approaches to defining the scope of the healthcare industry tend to adopt a broader definition, also including other key actions related to health, such as education and training of health professionals, regulation and management of health services delivery, provision of traditional and complementary medicines, and administration of health insurance.[8]

Providers and professionals

A healthcare provider is an institution (such as a hospital or clinic) or person (such as a physician, nurse, allied health professional or community health worker) that provides preventive, curative, promotional, rehabilitative or palliative care services in a systematic way to individuals, families or communities.

The World Health Organization estimates there are 9.2 million physicians, 19.4 million nurses and midwives, 1.9 million dentists and other dentistry personnel, 2.6 million pharmacists and other pharmaceutical personnel, and over 1.3 million community health workers worldwide,[9] making the health care industry one of the largest segments of the workforce.

The medical industry is also supported by many professions that do not directly provide health care itself, but are part of the management and support of the health care system. The incomes of managers and administrators, underwriters and medical malpractice attorneys, marketers, investors and shareholders of for-profit services, all are attributable to health care costs.[10]

In 2017, healthcare costs paid to hospitals, physicians, nursing homes, diagnostic laboratories, pharmacies, medical device manufacturers and other components of the healthcare system, consumed 17.9 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP) of the United States, the largest of any country in the world. It is expected that the health share of the Gross domestic product (GDP) will continue its upward trend, reaching 19.9 percent of GDP by 2025.[11] In 2001, for the OECD countries the average was 8.4 percent[12] with the United States (13.9%), Switzerland (10.9%), and Germany (10.7%) being the top three. US health care expenditures totaled US$2.2 trillion in 2006.[3] According to Health Affairs, US$7,498 be spent on every woman, man and child in the United States in 2007, 20 percent of all spending. Costs are projected to increase to $12,782 by 2016.[13]

The government does not ensure all-inclusive health care to every one of its residents. However, certain freely supported health care programs help to accommodate a portion of people who are elderly, disabled, or poor. Elected law guarantees community to crisis benefits paying little respect to capacity to pay. Those without health protection scope are relied upon to pay secretly for therapeutic administrations. Health protection is costly and hospital expenses are overwhelmingly the most well-known explanation behind individual liquidation in the United States.

Delivery of services

The delivery of healthcare services—from primary care to secondary and tertiary levels of care—is the most visible part of any healthcare system, both to users and the general public.[14] There are many ways of providing healthcare in the modern world. The place of delivery may be in the home, the community, the workplace, or in health facilities. The most common way is face-to-face delivery, where care provider and patient see each other in person. This is what occurs in general medicine in most countries. However, with modern telecommunications technology, in absentia health care or Tele-Health is becoming more common. This could be when practitioner and patient communicate over the phone, video conferencing, the internet, email, text messages, or any other form of non-face-to-face communication. Practices like these are especial applicable to rural regions in developed nations. These services are typically implemented on a clinic-by-clinic basis.[15]

Improving access, coverage and quality of health services depends on the ways services are organized and managed, and on the incentives influencing providers and users. In market-based health care systems, for example such as that in the United States, such services are usually paid for by the patient or through the patient's health insurance company. Other mechanisms include government-financed systems (such as the National Health Service in the United Kingdom). In many poorer countries, development aid, as well as funding through charities or volunteers, help support the delivery and financing of health care services among large segments of the population.[16]

The structure of healthcare charges can also vary dramatically among countries. For instance, Chinese hospital charges tend toward 50% for drugs, another major percentage for equipment, and a small percentage for healthcare professional fees.[17] China has implemented a long-term transformation of its healthcare industry, beginning in the 1980s. Over the first twenty-five years of this transformation, government contributions to healthcare expenditures have dropped from 36% to 15%, with the burden of managing this decrease falling largely on patients. Also over this period, a small proportion of state-owned hospitals have been privatized. As an incentive to privatization, foreign investment in hospitals—up to 70% ownership has been encouraged.[17]

Systems

Healthcare systems dictate the means by which people and institutions pay for and receive health services. Models vary based on the country with the responsibility of payment ranging from public (social insurance) and private health insurers to the consumer-driven by patients themselves. These systems finance and organize the services delivered by providers. A two-tier system of public and private is common.

The American Academy of Family Physicians define four commonly utilized systems of payment:

Beveridge model

Named after British economist and social reformer William Beveridge, the Beveridge model sees healthcare financed and provided by a central government.[18] The system was initially proposed in his 1942 report, Social Insurance and Allied Services—known as the Beveridge Report. The system is the guiding basis of the modern British healthcare model enacted post-World War II. It has been utilized in numerous countries, including The United Kingdom, Cuba, and New Zealand.[19]

The system sees all healthcare services— which are provided and financed solely by the government. This single payer system is financed through national taxation.[20] Typically, the government owns and runs the clinics and hospitals, meaning that doctors are employees of the government. However, depending on the specific system, public providers can be accompanied by private doctors who collect fees from the government.[19] The underlying principal of this system is that healthcare is a fundamental human right. Thus, the government provides universal coverage to all citizens.[21] Generally, the Beveridge model yields a low cost per capita compared to other systems.[22]

Bismarck model

The Bismarck system was first employed in 1883 by Prussian Chancellor Otto von Bismarck.[23] In this system, insurance is mandated by the government and is typically sold on a non-profit basis. In many cases, employers and employees finance insurers through payroll deduction. In a pure Bismarck system, access to insurance is seen as a right solely predicated on labor status. The system attempts to cover all working citizens, meaning patients cannot be excluded from insurance due to pre-existing conditions. While care is privatized, it is closely regulated by the state through fixed procedure pricing. This means that most insurance claims are reimbursed without challenge, creating low administrative burden.[23] Archetypal implementation of the Bismarck system can be seen in Germany's nationalized healthcare. Similar systems can be found in France, Belgium, and Japan.[24]

National health insurance model

The national insurance model shares and mixes elements from both the Bismarck and Beveridge models. The emergence of the National Health Insurance model is cited as a response to the challenges presented by the traditional Bismarck and Beveridge systems.[25] For instance, it is difficult for Bismarck Systems to contend with aging populations, as these demographics are less economically active.[26] Ultimately, this model has more flexibility than a traditional Bismarck or Beveridge model, as it can pull effective practices from both systems as needed.

This model maintains private providers, but payment comes directly from the government. Insurance plans control costs by paying for limited services. In some instances, citizens can opt out of public insurance for private insurance plans. However, large public insurance programs provide the government with bargaining power, allowing them to drive down prices for certain services and medication. In Canada, for instance, drug prices have been extensively lowered by the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board.[27] Examples of this model can be found in Canada, Taiwan, and South Korea.[28]

Out-of-pocket model

In areas with low levels of government stability or poverty, there is often no mechanism for ensuring that health costs are covered by a party other than the individual. In this case patients must pay for services on their own.[19] Payment methods can vary—ranging from physical currency, to trade for goods and services.[19] Those that cannot afford treatment typically remain sick or die.[19]

Inefficiencies

In countries where insurance is not mandated, there can be gaps in coverage—especially among disadvantaged and impoverished communities that can not afford private plans.[29] The UK National Health System creates excellent patient outcomes and mandates universal coverage but also has large lag times for treatment. Critics argue that reforms brought about by the Health and Social Care Act 2012 only proved to fragment the system, leading to high regulatory burden and long treatment delays.[30] In his review of NHS leadership in 2015, Sir Stuart Rose concluded that "the NHS is drowning in bureaucracy."[31]

See also

- Acronyms in healthcare

- Big Pharma

- Health administration

- Health care

- Health policy

- Health sciences

- Health system

- Health economics

- Hospital network

- Biotechnology

- Medicine

- Medicare fraud

- Pharmaceutical industry

- List of pharmaceutical companies

- Philosophy of healthcare

- Unnecessary health care

References

- ↑ HEALTH PROFESSIONS Archived 2019-05-01 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Health Care Initiatives, Employment & Training Administration (ETA) - U.S. Department of Labor". Doleta.gov. Archived from the original on 2012-01-29. Retrieved 2015-02-17.

- 1 2 "Snapshots: Comparing Projected Growth in Health Care Expenditures and the Economy | The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation". Kff.org. 2006-04-17. Archived from the original on 2013-04-02. Retrieved 2015-02-17.

- ↑ "Historical | CMS". www.cms.gov. Archived from the original on 2019-11-11. Retrieved 2021-10-29.

- ↑ "THE PHARMACEUTICAL INDUSTRY AND GLOBAL HEALTH - FACTS AND FIGURES 2021" (PDF). INTERNATIONAL FEDERATION OF PHARMACEUTICAL MANUFACTURERS & ASSOCIATIONS. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-02-01. Retrieved 2022-02-28.

- ↑ United Nations. International Standard Industrial Classification of All Economic Activities, Rev.3. Archived 2017-07-11 at the Wayback Machine New York.

- ↑ "Yahoo Industry Browser – Healthcare Sector – Industry List". Biz.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ↑ Hernandez P et al., "Measuring expenditure on the health workforce: concepts, data sources and methods", in: Handbook on monitoring and evaluation of human resources for health, Geneva, World Health Organization, 2009.

- ↑ World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2011 – Table 6: Health workforce, infrastructure and essential medicines. Geneva, 2011. Accessed 21 July 2011.

- ↑ Evans RG (1997). "Going for the gold: the redistributive agenda behind market-based health care reform" (PDF). J Health Polit Policy Law. 22 (2): 427–65. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.573.7172. doi:10.1215/03616878-22-2-427. PMID 9159711. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-10. Retrieved 2022-07-20.

- ↑ Keehan, Sean P.; Stone, Devin A.; Poisal, John A.; Cuckler, Gigi A.; Sisko, Andrea M.; Smith, Sheila D.; Madison, Andrew J.; Wolfe, Christian J.; Lizonitz, Joseph M. (March 2017). "National Health Expenditure Projections, 2016–25: Price Increases, Aging Push Sector To 20 Percent Of Economy". Health Affairs. 36 (3): 553–563. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1627. ISSN 0278-2715. PMID 28202501. S2CID 4927588. Archived from the original on 2022-11-12. Retrieved 2022-07-20.

- ↑ Archived March 20, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Average 2016 health-care bill: $12,782" by Ricardo Alonso-Zalvidar Los Angeles Times February 21, 2007

- ↑ "WHO | Health systems service delivery". Who.int. Archived from the original on March 27, 2006. Retrieved 2015-02-17.

- ↑ "Telehealth Use in Rural Healthcare Introduction - Rural Health Information Hub". www.ruralhealthinfo.org. Archived from the original on 2020-06-21. Retrieved 2018-10-29.

- ↑ Archived July 26, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 Robert Yuan (2007-06-15). "China Cultivates Its Healthcare Industry". Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News. Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. pp. 49–51. Archived from the original on 2020-04-14. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

(subtitle) The Risks and Opportunities in a Society Undergoing Explosive Change

- ↑ "The National Archives | Exhibitions | Citizenship | Brave new world". www.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 2021-01-26. Retrieved 2018-10-27.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Health Care Reform: Learning From Other Major Health Care Systems | Princeton Public Health Review". pphr.princeton.edu. Archived from the original on 2021-03-10. Retrieved 2018-10-27.

- ↑ Beveridge, William (1942). Social Insurance and Allied Services. Macmillan.

- ↑ Bevan, Gwyn; Helderman, Jan-Kees; Wilsford, David (July 2010). "Changing choices in health care: implications for equity, efficiency and cost". Health Economics, Policy and Law. 5 (3): 251–267. doi:10.1017/S1744133110000022. ISSN 1744-134X. PMID 20478104.

- ↑ Organization, World Health (2000). The World Health Report 2000: Health Systems : Improving Performance. World Health Organization. ISBN 9789241561983.

Britain.

- 1 2 Busse, Reinhard; Blümel, Miriam; Knieps, Franz; Bärnighausen, Till (2017-08-26). "Statutory health insurance in Germany: a health system shaped by 135 years of solidarity, self-governance, and competition". Lancet. 390 (10097): 882–897. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31280-1. ISSN 1474-547X. PMID 28684025.

- ↑ "Five Countries - Health Care Systems -- The Four Basic Models | Sick Around The World | FRONTLINE | PBS". www.pbs.org. Archived from the original on 2021-04-19. Retrieved 2018-10-27.

- ↑ van der Zee, Jouke; Kroneman, Madelon (2007-02-01). "Bismarck or Beveridge: A beauty contest between dinosaurs". BMC Health Services Research. 7: 94. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-7-94. PMC 1934356. PMID 17594476.

- ↑ Joël, Marie-Eve; Dufour-Kippelen, Sandrine (August 2002). "Financing systems of care for older persons in Europe". Aging Clinical and Experimental Research. 14 (4): 293–299. doi:10.1007/bf03324453. ISSN 1594-0667. PMID 12462375. S2CID 43533840.

- ↑ Office, U.S. Government Accountability (1993-02-22). "Prescription Drug Prices: Analysis of Canada's Patented Medicine Prices Review Board" (HRD-93-51). Archived from the original on 2021-02-25. Retrieved 2022-07-20.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Reid, T R (2009). The healing of America : a global quest for better, cheaper, and fairer health care. Penguin Press. ISBN 9781594202346.

- ↑ "The Coverage Gap: Uninsured Poor Adults in States that Do Not Expand Medicaid". The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2018-06-12. Archived from the original on 2020-10-17. Retrieved 2018-11-07.

- ↑ Group, British Medical Journal Publishing (2013-04-05). "Implementation of the Health and Social Care Act". BMJ. 346: f2173. doi:10.1136/bmj.f2173. ISSN 1756-1833. Archived from the original on 2021-02-28. Retrieved 2022-07-20.

- ↑ "Better leadership for tomorrow: NHS leadership review". GOV.UK. Archived from the original on 2020-11-08. Retrieved 2018-11-07.

Further reading

- Mahar, Maggie, Money-Driven Medicine: The Real Reason Health Care Costs So Much Archived 2022-11-12 at the Wayback Machine, Harper/Collins, 2006. ISBN 978-0-06-076533-0

- Meidinger, Roy (2015). Truth About Healthcare Industry. City: BookBaby. ISBN 978-1-4835-5003-9. OCLC 958576690.

The Truth About The Healthcare Industry, is it is an Oligopoly, an Industry, with very high costs and low quality of service. The book looks at the last 30 years and explains how this industry has stolen $21 trillion, through false billings, accounting fraud, kickbacks and restrained trade by using economic duress. As this industry expanded, it damaged other industries, especially the manufacturing industry, which closed 75,000 companies and caused the loss of 7 million manufacturing jobs. The book shows that the government has known for some time, has covered up the illegal practices, especially the IRS.