Palpitations

| Palpitation | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artistic impression of a woman experiencing syncope, which may be accompanied by heart palpitations | |

| Specialty | Cardiology |

| Differential diagnosis | Tachycardia |

Palpitations are perceived abnormalities of the heartbeat characterized by awareness of cardiac muscle contractions in the chest, which is further characterized by the hard, fast and/or irregular beatings of the heart.[1][2]

Symptoms include a rapid pulsation, an abnormally rapid or irregular beating of the heart.[1] Palpitations are a sensory symptom and are often described as a skipped beat, rapid fluttering in the chest, pounding sensation in the chest or neck, or a flip-flopping in the chest.[1]

Palpitation can be associated with anxiety and does not necessarily indicate a structural or functional abnormality of the heart, but it can be a symptom arising from an objectively rapid or irregular heartbeat. Palpitation can be intermittent and of variable frequency and duration, or continuous. Associated symptoms include dizziness, shortness of breath, sweating, headaches and chest pain.

Palpitation may be associated with coronary heart disease, hyperthyroidism, diseases affecting cardiac muscle such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, diseases causing low blood oxygen such as asthma and emphysema; previous chest surgery; kidney disease; blood loss and pain; anemia; drugs such as antidepressants, statins, alcohol, nicotine, caffeine, cocaine and amphetamines; electrolyte imbalances of magnesium, potassium and calcium; and deficiencies of nutrients such as taurine, arginine, iron, vitamin B12.[3]

Signs and symptoms

Three common descriptions of palpitation are "flip-flopping" (or "stop and start"), often caused by premature contraction of the atrium or ventricle, with the perceived "stop" from the pause following the contraction, and the "start" from the subsequent forceful contraction; rapid "fluttering in the chest", with regular "fluttering" suggesting supraventricular or ventricular arrhythmias (including sinus tachycardia) and irregular "fluttering" suggesting atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, or tachycardia with variable block; and "pounding in the neck" or neck pulsations, often due to cannon A waves in the jugular venous, pulsations that occur when the right atrium contracts against a closed tricuspid valve.[4]

Palpitation associated with chest pain suggests coronary artery disease, or if the chest pain is relieved by leaning forward, pericardial disease is suspected. Palpitation associated with light-headedness, fainting or near fainting suggest low blood pressure and may signify a life-threatening abnormal heart rhythm. Palpitation that occurs regularly with exertion suggests a rate-dependent bypass tract or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. If a benign cause for these concerning symptoms cannot be found at the initial visit, then ambulatory monitoring or prolonged heart monitoring in the hospital might be warranted. Noncardiac symptoms should also be elicited since the palpitations may be caused by a normal heart responding to a metabolic or inflammatory condition. Weight loss suggests hyperthyroidism. Palpitation can be precipitated by vomiting or diarrhea that leads to electrolyte disorders and hypovolemia. Hyperventilation, hand tingling, and nervousness are common when anxiety or panic disorder is the cause of the palpitations.[5]

Causes

The current knowledge of the neural pathways responsible for the perception of the heartbeat is not clearly elucidated. It has been hypothesized that these pathways include different structures located both at the intra-cardiac and extra-cardiac level.[1] Palpitations are a widely diffused complaint and particularly in subjects affected by structural heart disease.[1] The list of etiologies of palpitations is long, and in some cases, the etiology is unable to be determined.[1] In one study reporting the etiology of palpitations, 43% were found to be of cardiac etiology, 31% of psychiatric etiology and approximately 10% were classified as miscellaneous (medication induced, thyrotoxicosis, caffeine, cocaine, anemia, amphetamine, mastocytosis).[1]

The cardiac etiologies of palpitations are the most life-threatening and include ventricular sources (premature ventricular contractions (PVC), ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation), atrial sources (atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter) high output states (anemia, AV fistula, Paget's disease of bone or pregnancy), structural abnormalities (congenital heart disease, cardiomegaly, aortic aneurysm, or acute left ventricular failure), and miscellaneous sources (postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome abbreviated as POTS, Brugada syndrome, and sinus tachycardia).[1]

Palpitation can be attributed to one of four main causes:

- Extra-cardiac stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system (inappropriate stimulation of the sympathetic and parasympathetic, particularly the vagus nerve, (which innervates the heart), can be caused by anxiety and stress due to acute or chronic elevations in glucocorticoids and catecholamines.[1] Gastrointestinal distress such as bloating or indigestion, along with muscular imbalances and poor posture, can also irritate the vagus nerve causing palpitations)

- Sympathetic overdrive (panic disorder, low blood sugar, hypoxia, antihistamines (levocetirizine), low red blood cell count, heart failure, mitral valve prolapse).[6]

- Hyperdynamic circulation (valvular incompetence, thyrotoxicosis, hypercapnia, high body temperature, low red blood cell count, pregnancy).

- Abnormal heart rhythms (ectopic beat, premature atrial contraction, junctional escape beat, premature ventricular contraction, atrial fibrillation, supraventricular tachycardia, ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation, heart block).

Palpitations can occur during times of catecholamine excess, such as during exercise or at times of stress.[1] The cause of the palpitations during these conditions is often a sustained supraventricular tachycardia or ventricular tachyarrhythmia.[1] Supraventricular tachycardias can also be induced at the termination of exercise when the withdrawal of catecholamines is coupled with a surge in the vagal tone.[1] Palpitations secondary to catecholamine excess may also occur during emotionally startling experiences, especially in patients with a long QT syndrome.[1]

Psychiatric problems

Anxiety and stress elevate the body's level of cortisol and adrenaline, which in turn can interfere with the normal functioning of the parasympathetic nervous system resulting in overstimulation of the vagus nerve.[7] Vagus nerve induced palpitation is felt as a thud, a hollow fluttery sensation, or a skipped beat, depending on at what point during the heart's normal rhythm the vagus nerve fires. In many cases, the anxiety and panic of experiencing palpitations cause a patient to experience further anxiety and increased vagus nerve stimulation. The link between anxiety and palpitation may also explain why many panic attacks involve an impending sense of cardiac arrest. Similarly, physical and mental stress may contribute to the occurrence of palpitation, possibly due to the depletion of certain micronutrients involved in maintaining healthy psychological and physiological function.[8] Gastrointestinal bloating, indigestion and hiccups have also been associated with overstimulation of the vagus nerve causing palpitations, due to branches of the vagus nerve innervating the GI tract, diaphragm, and lungs.

Many psychiatric conditions can result in palpitations including depression, generalized anxiety disorder, panic attacks, and somatization. However one study noted that up to 67% of patients diagnosed with a mental health condition had an underlying arrhythmia.[1] There are many metabolic conditions that can result in palpitations including, hyperthyroidism, hypoglycemia, hypocalcemia, hyperkalemia, hypokalemia, hypermagnesemia, hypomagnesemia, and pheochromocytoma.[1]

Medication

The medications most likely to result in palpitations include sympathomimetic agents, anticholinergic drugs, vasodilators and withdrawal from beta blockers.[1][9]

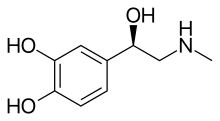

Common etiologies also include excess caffeine, or marijuana.[1] Cocaine, amphetamines, 3-4 methylenedioxymethamphetamine (Ecstasy or MDMA) can also cause palpitations.[1]

Pathophysiology

The sensation of palpitations can arise from extra-systoles or tachyarrhythmia.[1] It is very rarely noted due to bradycardia.[1] Palpitations can be described in many ways.[1] The most common descriptions include a flip-flopping in the chest, a rapid fluttering in the chest, or pounding in the neck.[1] The description of the symptoms may provide a clue regarding the etiology of the palpitations, and the pathophysiology of each of these descriptions is thought to be different.[1] In patients who describe the palpitations as a brief flip-flopping in the chest, the palpitations are thought to be caused by extra- systoles such as supraventricular or ventricular premature contractions.[1] The flip-flop sensation is thought to result from the forceful contraction following the pause, and the sensation that the heart is stopped results from the pause.[1] The sensation of rapid fluttering in the chest is thought to result from a sustained ventricular or supraventricular arrhythmia.[1] Furthermore, the sudden cessation of this arrythmia can suggest paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia.[1] This is further supported if the patient can stop the palpitations by using Valsalva maneuvers.[1] The rhythm of the palpitations may indicate the etiology of the palpitations (irregular palpitations indicate atrial fibrillation as a source of the palpitations).[1] An irregular pounding sensation in the neck can be caused by the dissociation of mitral valve and tricuspid valve, and the subsequent atria are contracting against a closed tricuspid and mitral valves, thereby producing cannon A waves.[1] Palpitations induced by exercise could be suggestive of cardiomyopathy, ischemia or channelopathies.[1]

Diagnosis

The most important initial clue to the diagnosis is one's description of palpitation. The approximate age of the person when first noticed and the circumstances under which they occur are important, as is information about caffeine intake (tea or coffee drinking), and whether continual palpitations can be stopped by deep breathing or changing body positions. It is also very helpful to know how they start and stop (abruptly or not), whether or not they are regular, and approximately how fast the pulse rate is during an attack. If the person has discovered a way of stopping the palpitations, that is also helpful information.[1]

A complete and detailed history and physical examination are two essential elements of the evaluation of a patient with palpitations.[1] The key components of a detailed history include age of onset, description of the symptoms including rhythm, situations that commonly result in the symptoms, mode of onset (rapid or gradual), duration of symptoms, factors that relieve symptoms (rest, Valsalva), positions and other associated symptoms such as chest pain, lightheadedness or syncope. A patient can tap out the rhythm to help demonstrate if they are not currently experiencing the symptoms. The patient should be questioned regarding all medications, including over-the-counter medications. Social history, including exercise habits, caffeine consumption, alcohol and illicit drug use, should also be determined. Also, past medical history and family history may provide indications to the etiology of the palpitations.[1]

Palpitations that have been a condition since childhood are most likely caused by a supraventricular tachycardia, whereas palpitations that first occur later in life are more likely to be secondary to structural heart disease.[1] A rapid regular rhythm is more likely to be secondary to paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia or ventricular tachycardia, and a rapid and irregular rhythm is more likely to be an indication of atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, or tachycardia with variable block.[1] Supraventricular and ventricular tachycardia is thought to result in palpitations with abrupt onset and abrupt termination.[1] In patients who can terminate their palpitations with a Valsalva maneuver, this is thought to indicate possibly a supraventricular tachycardia.[1] Palpitations associated with chest pain may suggest myocardial ischemia.[1] Lastly, when lightheadedness or syncope accompanies the palpitations, ventricular tachycardia, supraventricular tachycardia, or other arrhythmias should be considered.[1]

The diagnosis is usually not made by a routine medical examination and scheduled electrical tracing of the heart's activity (ECG) because most people cannot arrange to have their symptoms be present while visiting the hospital.[1] Nevertheless, findings such as a heart murmur or an abnormality of the ECG might be indicative of probable diagnosis. In particular, ECG changes that are associated with specific disturbances of the heart rhythm may be noticed; thus physical examination and ECG remain important in the assessment of palpitation.[1] Moreover, a complete physical exam should be performed including vital signs (with orthostatic vital signs), cardiac auscultation, lung auscultation, and examination of extremities.[1] A patient can tap out the rhythm to help demonstrate what they felt previously, if they are not currently experiencing the symptoms.[1]

Positive orthostatic vital signs may indicate dehydration or an electrolyte abnormality.[1] A mid-systolic click and heart murmur may indicate mitral valve prolapse.[1] A harsh holo-systolic murmur best heard at the left sternal border which increases with Valsalva may indicate hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy.[1] An irregular rhythm indicates atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter.[1] Evidence of cardiomegaly and peripheral edema may indicate heart failure and ischemia or a valvular abnormality.[1]

Blood tests, particularly tests of thyroid gland function, are also important baseline investigations (an overactive thyroid gland is a potential cause for palpitations; the treatment, in that case, is to treat the thyroid gland over-activity).

The next level of diagnostic testing is usually 24-hour (or longer) ECG monitoring, using a recorder called a Holter monitor, which can record the ECG continuously during a 24-hour or 48-hour period. If symptoms occur during monitoring it is a simple matter to examine the ECG recording and see what the cardiac rhythm was at the time. For this type of monitoring to be helpful, the symptoms must be occurring at least once a day. If they are less frequent, the chances of detecting anything with continuous 24- or even 48-hour monitoring are substantially lowered. More recent technology such as the Zio Patch allows continuous recording for up to 14 days; the patient indicates when symptoms occur by pushing a button on the device and keeps a log of the events.

Other forms of monitoring are available, and these can be useful when symptoms are infrequent. A continuous-loop event recorder monitors the ECG continuously, but only saves the data when the wearer activates it. Once activated, it will save the ECG data for a period of time before the activation and for a period of time afterwards – the cardiologist who is investigating the palpitations can program the length of these periods. An implantable loop recorder may be helpful in people with very infrequent but disabling symptoms. This recorder is implanted under the skin on the front of the chest, like a pacemaker. It can be programmed and the data examined using an external device that communicates with it by means of a radio signal.

Investigation of heart structure can also be important. The heart in most people with palpitation is completely normal in its physical structure, but occasionally abnormalities such as valve problems may be present. Usually, but not always, the cardiologist will be able to detect a murmur in such cases, and an ultrasound scan of the heart (echocardiogram) will often be performed to document the heart's structure. This is a painless test performed using sound waves and is virtually identical to the scanning done in pregnancy to look at the fetus.

Evaluation

A 12-lead electrocardiogram must be performed on every patient complaining of palpitations.[1] The presence of a short PR interval and a delta wave (Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome) is an indication of the existence of ventricular pre-excitation.[1] Significant left ventricular hypertrophy with deep septal Q waves in I, L, and V4 through V6 may indicate hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy.[1] The presence of Q waves may indicate a prior myocardial infarction as the etiology of the palpitations, and a prolonged QT interval may indicate the presence of the long QT syndrome.[1]

Laboratory studies should be limited initially.[1] Complete blood count can assess for anemia and infection.[1] Serum urea, creatinine and electrolytes to assess for electrolyte imbalances and renal dysfunction.[1] Thyroid function tests may demonstrate a hyperthyroid state.[1]

Most patients have benign conditions as the etiology for their palpitations.[1] The goal of further evaluation is to identify those patients who are at high risk for an arrhythmia.[1] Recommended laboratory studies include an investigation for anemia, hyperthyroidism and electrolyte abnormalities.[1] Echocardiograms are indicated for patients in whom structural heart disease is a concern.[1]

Further diagnostic testing is recommended for those in whom the initial diagnostic evaluation (history, physical examination, and EKG) suggest an arrhythmia, those who are at high risk for an arrhythmia, and those who remain anxious to have a specific explanation of their symptoms.[1] People considered to be at high risk for an arrhythmia include those with organic heart disease or any myocardial abnormality that may lead to serious arrhythmias.[1] These conditions include a scar from myocardial infarction, idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy, clinically significant valvular regurgitant, or stenotic lesions and hypertrophic cardiomyopathies.[1]

An aggressive diagnostic approach is recommended for those at high risk and can include ambulatory monitoring or electrophysiologic studies.[1] There are three types of ambulatory EKG monitoring devices: Holter monitor, continuous-loop event recorder, and an implantable loop recorder.[1]

People who are going to have these devices checked should be made aware of the properties of the devices and the accompanying course of the examination for each device.[1] The Holter monitor is a 24-hour monitoring system that is worn by exam takers themselves and records and continuously saves data.[1] Holter monitors are typically worn for a few days.[1] The continuous-loop event recorders are also worn by the exam taker and continuously record data, but the data is saved only when someone manually activates the monitor.[1] The continuous-loop recorders can be long worn for longer periods of time than the Holter monitors and therefore have been proven to be more cost-effective and efficacious than Holter monitors.[1] Also, because the person triggers the device when he/she feel the symptoms, they are more likely to record data during palpitations.[1] An implantable loop recorder is a device that is placed subcutaneously and continuously monitors for cardiac arrhythmias.[1] These are most often used in those with unexplained syncope and can be used for longer periods of time than the continuous loop event recorders. An implantable loop recorder is a device that is placed subcutaneously and continuously monitors for the detection of cardiac arrhythmias.[1] These are most often used in those with unexplained syncope and are a used for longer periods of time than the continuous loop event recorders.[1] Electrophysiology testing enables a detailed analysis of the underlying mechanism of the cardiac arrhythmia as well as the site of origin.[1] EPS studies are usually indicated in those with a high pretest likelihood of a serious arrhythmia.[1] The level of evidence for evaluation techniques is based upon consensus expert opinion.[1]

Treatment

Treating palpitation will depend on the severity and cause of the condition.[1] Radiofrequency ablation can cure most types of supraventricular and many types of ventricular tachycardias.[1] While catheter ablation is currently a common treatment approach, there have been advances in stereotactic radioablation for certain arrythmias.[1] This technique is commonly used for solid tumors and has been applied with success in management of difficult to treat Ventricular Tachycardia and Atrial Fibrillation.[1]

The most challenging cases involve palpitations that are secondary to supraventricular or ventricular ectopy or associated with normal sinus rhythm.[1] These conditions are thought to be benign, and the management involves reassurance of the patient that these arrhythmias are not life-threatening.[1] In these situations when the symptoms are unbearable or incapacitating, treatment with beta-blocking medications could be considered, and may provide a protective effect for otherwise healthy individuals.[1]

People who present to the emergency department who are asymptomatic, with unremarkable physical exams, have non-diagnostic EKGs and normal laboratory studies, can safely be sent home and instructed to follow up with their primary care provider or cardiologist.[1] Patients whose palpitations are associated with syncope, uncontrolled arrhythmias, hemodynamic compromise, or angina should be admitted for further evaluation.[1]

Palpitation that is caused by heart muscle defects will require specialist examination and assessment. Palpitation that is caused by vagus nerve stimulation rarely involves physical defects of the heart. Such palpitations are extra-cardiac in nature, that is, palpitation originating from outside the heart itself. Accordingly, vagus nerve induced palpitation is not evidence of an unhealthy heart muscle.

Treatment of vagus nerve induced palpitation will need to address the cause of irritation to the vagus nerve or the parasympathetic nervous system generally. It is of significance that anxiety and stress are strongly associated with increased frequency and severity of vagus nerve induced palpitation. Anxiety and stress reduction techniques such as meditation and massage may prove extremely beneficial to reduce or eliminate symptoms temporarily. Changing body position (e.g. sitting upright rather than lying down) may also help reduce symptoms due to the vagus nerve's innervation of several structures within the body such as the GI tract, diaphragm and lungs.

Prognosis

Direct-to-consumer options for monitoring heart rate and heart rate variability have become increasingly prevalent using smartphones and smartwatches.[1] These monitoring systems have become increasingly validated and may help provide early identification for those at risk for a serious arrhythmia such as atrial fibrillation.[1]

Palpitations can be a very concerning symptom for people.[1] The etiology of the palpitations in most patients is benign.[1] Therefore, comprehensive workups are not indicated.[1] However appropriate follow up with the primary care provider can provide the ability to monitor symptoms over time and determine if consultation with cardiologist is required.[1] People who are determined to be at high risk for palpitations of serious or life-threatening etiologies require a more extensive workup and comprehensive management.[1]

Once a cause is determined, the recommendations for treatment are quite strong with moderate to high quality therapies studied.[1] Partnership with the people who have the chief complaint of palpitation, using a shared decision-making model and involving an interprofessional team including a nurse, nurse practitioner, physician assistant, and physician can help best direct therapy and provide good followup.[1]

Prevalence

Palpitations are a common complaint in the general population, particularly in those affected by structural heart disease.[1] Clinical presentation is divided into four groups: extra-systolic, tachycardic, anxiety-related, and intense.[1] Anxiety-related is the most common.[1]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 Robinson, Kenneth J.; Sanchack, Kristian E. (2019-02-25). Palpitations in StatPearls. StatPearls. PMID 28613787. Retrieved 2019-03-30 – via NCBI Bookshelf.

This source from PubMed is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This source from PubMed is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. - ↑ Japp, Alan G.; Robertson, Colin; Wright, Rohana J.; Reed, Matthew J.; Robson, Andrew (2018). "26. Palpitations". Macleod's Clinical Diagnosis (2nd ed.). Elsevier. pp. 232–239. ISBN 978-0-7020-6962-8. Archived from the original on 2022-11-15. Retrieved 2022-11-16.

- ↑ "Vitamins That Can Cause Heart Palpitations". LIVESTRONG.COM. Archived from the original on 2021-09-04. Retrieved 2021-09-04.

- ↑ Indik, Julia H. (2010). "When Palpitations Worsen". The American Journal of Medicine. 123 (6): 517–9. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.01.012. PMID 20569756.

- ↑ Jamshed, N; Dubin, J; Eldadah, Z (February 2013). "Emergency management of palpitations in the elderly: epidemiology, diagnostic approaches, and therapeutic options". Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. 29 (1): 205–30. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2012.10.003. PMID 23177608.

- ↑ "MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia: Heart palpitations". Archived from the original on 2016-07-05. Retrieved 2022-10-05.

- ↑ content team, content team (July 18, 2019). "It is Time to Know Key Facts about Heart Palpitations". sinahealthtour.com. Archived from the original on July 21, 2019. Retrieved July 25, 2019.

- ↑ Cernak, I; Savic, V; Kotur, J; Prokic, V; Kuljic, B; Grbovic, D; Veljovic, M (2000). "Alterations in magnesium and oxidative status during chronic emotional stress". Magnesium Research. 13 (1): 29–36. PMID 10761188.

- ↑ Weitz, HH; Weinstock, PJ (1995). "Approach to the patient with palpitations". The Medical Clinics of North America. 79 (2): 449–56. doi:10.1016/S0025-7125(16)30078-5. ISSN 0025-7125. PMID 7877401.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia, NIH Archived 2016-07-05 at the Wayback Machine