Histoplasma capsulatum

| Histoplasma capsulatum | |

|---|---|

| |

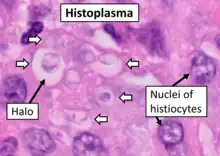

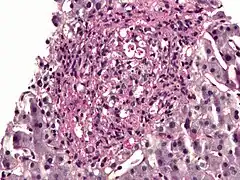

| Histopathology of Histoplasma capsulatum, H&E stain, showing organisms surrounded by halos, in a granuloma of epithelioid histiocytes. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Division: | Ascomycota |

| Class: | Eurotiomycetes |

| Order: | Onygenales |

| Family: | Ajellomycetaceae |

| Genus: | Histoplasma |

| Species: | H. capsulatum |

| Binomial name | |

| Histoplasma capsulatum Darling (1906) | |

Histoplasma capsulatum is a species of dimorphic fungus. Its sexual form is called Ajellomyces capsulatus. It can cause pulmonary and disseminated histoplasmosis.

H. capsulatum is "distributed worldwide, except in Antarctica, but most often associated with river valleys"[1] and occurs chiefly in the "Central and Eastern United States"[2] followed by "Central and South America, and other areas of the world".[2] It is most prevalent in the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys. It was discovered by Samuel Taylor Darling in 1906.

Morphology

H. capsulatum is an ascomycetous fungus closely related to Blastomyces dermatitidis. It is potentially sexual, and its sexual state, Ajellomyces capsulatus, can readily be produced in culture, though it has not been directly observed in nature. H. capsulatum groups with B. dermatitidis and the South American pathogen Paracoccidioides brasiliensis in the recently recognized fungal family Ajellomycetaceae.[3][4] It is dimorphic and switches from a mould-like (filamentous) growth form in the natural habitat to a small, budding yeast form in the warm-blooded animal host.

Like B. dermatitidis, H. capsulatum has two mating types, "+" and "–". The great majority of North American isolates belongs to a single genetic type,[5][6] but a study of multiple genes suggests a recombining, sexual population.[6] A recent analysis has suggested that the prevalent North American genetic type and a less common type should be considered separate phylogenetic species, distinct from H. capsulatum isolates obtained in Central and South America and other parts of the world. These entities are temporarily designated NAm1 (the rare type, which includes a famous experimental isolate designated "the Downs strain") and NAm2 (the common type).[6] As yet, no well-established clinical or geographic distinction is seen between these two genetic groups.

In its asexual form, the fungus grows as a colonial microfungus strongly similar in macromorphology to B. dermatitidis. A microscopic examination shows a marked distinction: H. capsulatum produces two types of conidia, globose macroconidia, 8–15 µm, with distinctive tuberculate or finger-like cell wall ornamentation, and ovoid microconidia, 2–4 µm, which appear smooth or finely roughened. Whether either of these conidial types is the principal infectious particle is unclear. They form on individual short stalks and readily become airborne when the colony is disturbed. Ascomata of the sexual state are 80–250 µm, and are very similar in appearance and anatomy to those described above for B. dermatitidis. The ascospores are similarly minute, averaging 1.5 µm.

The budding yeast cells formed in infected tissues are small (about 2–4 µm) and are characteristically seen forming in clusters within phagocytic cells, including histiocytes and other macrophages, as well as monocytes. An African phylogenetic species, H. duboisii, often forms larger yeast cells to 15 µm.

Geographic distribution

H. capsulatum is "distributed worldwide, except in Antarctica, but most often associated with river valleys"[1] and occurs chiefly in the "Central and Eastern United States"[2] followed by "Central and South America, and other areas of the world"[2] It is most prevalent in the Ohio and Mississippi river valleys.

The enzootic and endemic zones of H. capsulatum can be roughly divided into core areas, where the fungus occurs widely in soil or on vegetation contaminated by bird droppings or equivalent organic inputs, and peripheral areas, where the fungus occurs relatively rarely in association with soil, but is still found abundantly in heavy accumulations of bat or bird guano in enclosed spaces such as caves, buildings, and hollow trees. The principal core area for this species includes the valleys of the Mississippi, Ohio, and Potomac Rivers in the USA, as well as a wide span of adjacent areas extending from Kansas, Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio in the north to Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas in the south.[7][8][9] In some areas, such as Kansas City, skin testing with the histoplasmin antigen preparation shows that 80–90% of the resident population have an antibody reaction to H. capsulatum, probably indicating prior subclinical infection.[7] Northern U.S. states such as Minnesota, Michigan, New York and Vermont are peripheral areas for histoplasmosis, but have scattered counties where 5–19% of lifetime residents show exposure to H. capsulatum. One New York county, St. Lawrence county (across the St. Lawrence River from the Cornwall– Preston – Brockville area of Ontario, Canada) shows exposures over 20%.[7]

The distribution of H. capsulatum in Canada is not as well documented as in the US. The St. Lawrence Valley is probably the best known endemic region based both on case reports and on a number of skin test reaction studies that were done between 1945 and 1970. The Montreal area is a particularly well documented endemic focus, not just in the agricultural regions surrounding the city[10] but also within the city itself.[11] The Mount Royal area in central Montreal, especially the north and east sides of Mt. Royal Park, showed exposure rates between 20 and 50% in schoolchildren[11] and locally lifetime-resident university students.[12] A particularly high rate of 79.3% exposure was shown in St. Thomas, Ontario, south of London, Ontario, after 7 local residents had died of histoplasmosis in 1957.[13] Based on numerous small regional studies, histoplasmin skin test reactors form ca. 10–50 % of the population in much of southern Ontario and in Quebec’s St. Lawrence Valley, ca. 5% in southern Manitoba and some northerly parts of Quebec (e.g., Abitibi-Témiscamingue), and ca. 1% in Nova Scotia.[12][13][14][15][16] Exposure of aboriginal Canadians occurs remarkably far north in Quebec,[17][18] but has not been reported in similar boreal biogeoclimatic zones in many other parts of Canada. Recently and remarkably, a cluster of four indigenously acquired cases of histoplasmosis was shown to be associated with a golf course in suburban Edmonton, Alberta.[19] Examination suggested that local soil was the source.

Disease

Histoplasmosis is usually a subclinical infection that does not come to the attention of the person involved. The organism tends to remain alive in the scattered pulmonary calcifications; therefore, some cases are detected by emergence of serious infection when a patient becomes immunocompromised, perhaps decades later. Frank cases are most often seen as acute pulmonary histoplasmosis, a disease that resembles acute pneumonia but is usually self-limited.[7][20] It is most often seen in children newly exposed to H. capsulatum or in heavily exposed individuals. Erythematous skin conditions arising from antigen reactions may complicate the disease, as may myalgias, arthralgias, and rarely, arthritic conditions. Emphysema sufferers may contract chronic cavitary pulmonary histoplasmosis as a disease complication; eventually the cavity formed may be occupied by an Aspergillus fungus ball (aspergilloma), potentially leading to massive hemoptysis.[20] Another uncommon form of histoplasmosis is a slowly progressing condition known as granulomatous mediastinitis, in which the lymph nodes in the mediastinal cavity between the lungs become inflamed and ultimately necrotic; the swollen nodes or draining fluid may ultimately affect the bronchi, the superior vena cava, the esophagus or the pericardium. A particularly dangerous condition is mediastinal fibrosis, in which a subset of individuals with granulomatous mediastinitis develop an uncontrolled fibrotic reaction that may press on the lungs or the bronchi, or may cause right heart failure. There are a number of other rare pulmonary manifestations of histoplasmosis.

Histoplasmosis, like blastomycosis, may disseminate haematogenously to infect internal organs and tissues, but it does so in a very low proportion of cases, and half or more of these dissemination cases involve immunocompromisation. Unlike blastomycosis, histoplasmosis is a recognized AIDS-defining illness in people with HIV infection; disseminated histoplasmosis affects approximately 5% of AIDS patients with CD4+ cell counts <150 cells/µL in highly endemic areas.[21] The incidence of this condition dropped significantly after introduction of current anti-HIV therapies.[20] Other conditions very uncommonly associated with H. capsulatum include endocarditis and peritonitis.[7][22]

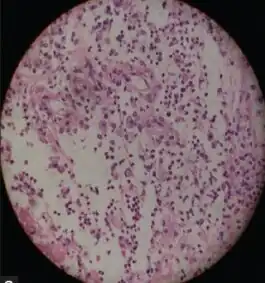

Histopathology of Histoplasma capsulatum, GMS stain, showing narrow budding yeast

Histopathology of Histoplasma capsulatum, GMS stain, showing narrow budding yeast H. capsulatum. Methenamine silver stain.

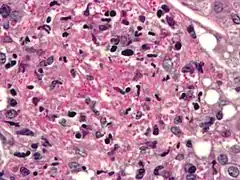

H. capsulatum. Methenamine silver stain. Histoplasma (bright red, small, circular). PAS diastase stain

Histoplasma (bright red, small, circular). PAS diastase stain Histoplasma. PAS diastase stain.

Histoplasma. PAS diastase stain. Histoplasma in a granuloma. PAS diastase stain.

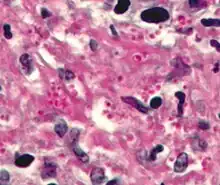

Histoplasma in a granuloma. PAS diastase stain. Histoplasma in a granuloma. GMS stain.

Histoplasma in a granuloma. GMS stain.

Ecology and epidemiology

H. capsulatum appears to be strongly associated with the droppings of certain bird species as well as bats.[7] A mixture of these droppings and certain soil types is particularly conducive to proliferation. In highly endemic areas there is a strong association with soil under and around chicken houses, and with areas where soil or vegetation has become heavily contaminated with faecal material deposited by flocking birds such as starlings and blackbirds. Bird roosting areas that are Histoplasma-free appear to be lower in nitrogen, phosphorus, organic matter and moisture than contaminated roosting areas.[7] The guano of gulls and other colonially nesting water-associated birds is rarely connected to histoplasmosis.[23] Bat dwellings, including caves, attics and hollow trees, are classic H. capsulatum habitats.[7][22]

Histoplasmosis outbreaks are typically associated with cleaning guano accumulations or clearing guano-covered vegetation, or with exploration of bat caves. In addition, however, outbreaks may be associated with wind-blown dust liberated by construction projects in endemic areas: a classic outbreak is one associated with intense construction activity, including subway construction, in Montreal in 1963.[24]

As with blastomycosis, a good understanding of the precise ecological affinities of H. capsulatum is greatly complicated by the difficulty of isolating the fungus directly from nature. Again, the mouse passage procedure originally devised by Emmons[25] must be used. A direct PCR technique for detection of H. capsulatum in soil has been published.[26] H. capsulatum appears particularly likely to cause clinical disease in young children, persons working in sites contaminated by conducive bird or bat droppings, persons exposed to construction dust raised from contaminated sites, immunocompromised patients, and emphysema sufferers. Elimination of the agent from contaminated soils typically involves the use of toxic fumigants with limited success.[27]

Etymology

In 1905, Samuel Taylor Darling serendipitously identified a protozoan-like microorganism in an autopsy specimen while trying to understand malaria, which was prevalent during the construction of the Panama Canal. He named this microorganism Histoplasma capsulatum because it invaded the cytoplasm (plasma) of histiocyte-like cells (Histo) and had a refractive halo mimicking a capsule (capsulatum), a misnomer. [28]

See also

- Blastomyces

- Coccidioides

References

- 1 2 Chiller, Tom M. (2016), "Histoplasmosis", CDC Yellow Book: CDC Health Information for International Travel, archived from the original on 2017-02-07, retrieved 2023-06-02.

- 1 2 3 4 CDC (2014), Fungal Diseases > Global fungal diseases > Preventing Deaths from Histoplasmosis, archived from the original on 2014-10-09, retrieved 2023-06-02.

- ↑ Untereiner, W.A.; Scott, J.A.; Naveau, F.A.; Bachewich, J. (2002). "Phylogeny of Ajellomyces, Polytolypa and Spiromastix (Onygenaceae) inferred from rDNA sequence and non-molecular data". Studies in Mycology. 47: 25–35.

- ↑ Untereiner, WA; Scott, JA; Naveau, FA; Sigler, L; Bachewich, J; Angus, A (2004). "The Ajellomycetaceae, a new family of vertebrate-associated Onygenales". Mycologia. 96 (4): 812–821. doi:10.2307/3762114. JSTOR 3762114. PMID 21148901.

- ↑ Karimi, K; Wheat, LJ; Connolly, P; Cloud, G; Hajjeh, R; Wheat, E; Alves, K; Lacaz Cd Cda, S; Keath, E (1 December 2002). "Differences in histoplasmosis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in the United States and Brazil". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 186 (11): 1655–1660. doi:10.1086/345724. PMID 12447743.

- 1 2 3 Kasuga, T; White, TJ; Koenig, G; McEwen, J; Restrepo, A; Castañeda, E; Da Silva Lacaz, C; Heins-Vaccari, EM; De Freitas, RS; Zancopé-Oliveira, RM; Qin, Z; Negroni, R; Carter, DA; Mikami, Y; Tamura, M; Taylor, ML; Miller, GF; Poonwan, N; Taylor, JW (2003). "Phylogeography of the fungal pathogen Histoplasma capsulatum". Molecular Ecology. 12 (12): 3383–401. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294x.2003.01995.x. PMID 14629354. S2CID 13060796. Archived from the original on 2022-03-28. Retrieved 2023-06-02.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Kwon-Chung, K. June; Bennett, Joan E. (1992). Medical mycology. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger. ISBN 978-0812114638.

- ↑ Chamany, S; Mirza, SA; Fleming, JW; Howell, JF; Lenhart, SW; Mortimer, VD; Phelan, MA; Lindsley, MD; Iqbal, NJ; Wheat, LJ; Brandt, ME; Warnock, DW; Hajjeh, RA (2004). "A large histoplasmosis outbreak among high school students in Indiana, 2001". The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 23 (10): 909–14. doi:10.1097/01.inf.0000141738.60845.da. PMID 15602189. S2CID 23475233.

- ↑ Stobierski, MG; Hospedales, CJ; Hall, WN; Robinson-Dunn, B; Hoch, D; Sheill, DA (1996). "Outbreak of histoplasmosis among employees in a paper factory--Michigan, 1993". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 34 (5): 1220–1223. doi:10.1128/JCM.34.5.1220-1223.1996. PMC 228985. PMID 8727906.

- ↑ Guy, R; Roy, O (1949). "Histoplasmin sensitivity; preliminary observations in a group of school children in the Province of Quebec". Canadian Journal of Public Health. 40 (2): 68–71. PMID 18113223.

- 1 2 Leznoff, A; Frank, H; Taussig, A; Brandt, JL (1969). "The focal distribution of histoplasmosis in Montreal". Canadian Journal of Public Health. 60 (8): 321–5. PMID 5806145.

- 1 2 MacEachern, EJ; McDonald, JC (1971). "Histoplasmin sensitivity in McGill University students". Canadian Journal of Public Health. 62 (5): 415–422. PMID 5137623.

- 1 2 Haggar, R.A; Brown, E.L.; Toplack, N.J. (1957). "Histoplasmosis in South Western Ontario". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 77 (9): 855–861. PMC 1824134. PMID 13472567.

- ↑ Rostocka, M; Hiltz, JE (1966). "Histoplasmin skin sensitivity in Nova Scotia". Canadian Journal of Public Health. 57 (9): 413–418. PMID 5981243.

- ↑ Hoff, B.; Fogle, B. (1970). "Case report. Histoplasmosis in a dog". Canadian Veterinary Journal. 11 (7): 145–148. PMC 1695089. PMID 5464271.

- ↑ Mochi, A; Edwards, PQ (1952). "Geographical distribution of histoplasmosis and histoplasmin sensitivity". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 5 (3): 259–291. PMC 2554039. PMID 14935779.

- ↑ Guy, R; Panisset, M; Frappier, A (1949). "Histoplasmin sensitivity; a brief study of the incidence of hypersensitivity to histoplasmin in an Indian tribe of northern Quebec". Canadian Journal of Public Health. 40 (7): 306–309. PMID 18133141.

- ↑ Schaefer, O (1966). "Pulmonary miliary calcification and histoplasmin sensitivity in Canadian eskimos". Canadian Journal of Public Health. 57 (9): 410–418. PMID 5977447.

- ↑ Anderson, Heather; Honish, Lance; Taylor, Geoff; Johnson, Marcia; Tovstiuk, Chrystyna; Fanning, Anne; Tyrrell, Gregory; Rennie, Robert; Jaipaul, Joy; Sand, Crystal; Probert, Steven (2006). "Histoplasmosis Cluster, Golf Course, Canada". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 12 (1): 163–165. doi:10.3201/eid1201.051083. PMC 3291405. PMID 16494738.

- 1 2 3 Kauffman, C. A. (2007). "Histoplasmosis: a Clinical and Laboratory Update". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 20 (1): 115–132. doi:10.1128/CMR.00027-06. PMC 1797635. PMID 17223625.

- ↑ Hajjeh, RA (1995). "Disseminated histoplasmosis in persons infected with human immunodeficiency virus". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 21 Suppl 1: S108–10. doi:10.1093/clinids/21.supplement_1.s108. PMID 8547497.

- 1 2 Rippon, John Willard (1988). Medical mycology: the pathogenic fungi and the pathogenic actinomycetes (3rd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders. ISBN 978-0721624440.

- ↑ Waldman, RJ; England, AC; Tauxe, R; Kline, T; Weeks, RJ; Ajello, L; Kaufman, L; Wentworth, B; Fraser, DW (1983). "A winter outbreak of acute histoplasmosis in northern Michigan". American Journal of Epidemiology. 117 (1): 68–75. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113517. PMID 6823954.

- ↑ Leznoff, A; Frank, H; Telner, P; Rosensweig, J; Brandt, JL (1964). "Histoplasmosis in Montreal during the fall of 1963, with observations on erythema multiforme". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 91 (22): 1154–1160. PMC 1928451. PMID 14226089.

- ↑ Emmons, C.W. (1961). "Isolation of Histoplasma capsulatum from soil in Washington, D.C." Public Health Reports. 76 (591–596): 591–5. doi:10.2307/4591218. JSTOR 4591218. PMC 1929641. PMID 13696714.

- ↑ Reid, TM; Schafer, MP (1999). "Direct detection of Histoplasma capsulatum in soil suspensions by two-stage PCR". Molecular and Cellular Probes. 13 (4): 269–273. doi:10.1006/mcpr.1999.0247. PMID 10441199.

- ↑ Ajello, L.; Weeks, R.J. (1983). "Soil decontamination and other control measures". In DiSalvo, Arthur F. (ed.). Occupational mycoses. Philadelphia, Pa.: Lea and Febiger. pp. 229–238. ISBN 9780812108859.

- ↑ Mahajan, Monika (2021). "Etymologia: Histoplasma capsulatum". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 27 (3): 969. doi:10.3201/eid2703.et2703.

Citing public domain text from the CDC