Blastomycosis

| Blastomycosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names: North American blastomycosis, Gilchrist's disease[1] | |

| |

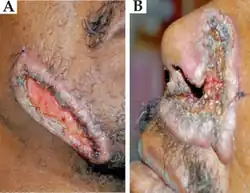

| Skin lesions of blastomycosis. | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms |

|

| Causes | Blastomyces dermatitidis[1] |

| Treatment | Antifungals[3] |

| Medication | Itraconazole, amphotericin B[3] |

Blastomycosis, also known as Gilchrist's disease, is a fungal infection, typically of the lungs, which can spread to brain, stomach, intestine and skin, where it appears as crusting purplish warty plaques with a roundish bumpy edge and central depression.[1][4] Around half have symptoms which may include fever, cough, night sweats, muscle pains, weight loss, chest pain, and feeling tired.[2] These symptoms usually develop between three weeks and three months after breathing in the spores.[2] In those with weak immune systems, the disease can spread to other areas of the body and become widespread.[5]

It is caused by breathing in spores of Blastomyces dermatitidis, a common mold, which generally affects people who cannot fight infection themselves due to their medication or medical condition.[1][6] B. dermatitis is found in soil and decaying organic matter like wood or leaves.[7] Participating in outdoor activities like hunting or camping in wooded areas increases the risk of developing blastomycosis.[8]

There is no vaccine, but the disease can be prevented by not disturbing the soil.[8] Treatment is with itraconazole for mild or moderate disease and amphotericin B for severe disease.[7] With both, the duration of treatment is 6–12 months.[9]

Overall, 4-6% of people who develop blastomycosis die; however, if the central nervous system is involved, this rises to 18%. People with AIDS or on medications that suppress the immune system have the highest risk of death at 25-40%.[10]

Blastomycosis is most common in the eastern United States, especially along the Ohio river, Mississippi River valleys, the Great Lakes, and the St. Lawrence River.[1] It is also endemic to some parts of Canada, including Quebec, Ontario, and Manitoba.[7] In these areas, there are about 1 to 2 cases per 100,000 per year.[11] Blastomycosis was first described by Thomas Caspar Gilchrist in 1894.[12]

Signs and symptoms

The severity of symptoms depends on a person's immune status; less than 50% of healthy people with blastomycosis have symptoms, while immunocompromised patients can have the disease spread beyond the lungs to other organs like the skin and bones.[5]

Blastomycosis can present in one of the following ways:

- a flu-like illness with fever, chills, arthralgia (joint pain), myalgia (muscle pain), headache, and a nonproductive cough which resolves within days.

- an acute illness resembling bacterial pneumonia, with symptoms of high fever, chills, a productive cough, and pleuritic chest pain.

- a chronic illness that mimics tuberculosis or lung cancer, with symptoms of low-grade fever, a productive cough, night sweats, and weight loss.

- a fast, progressive, and severe disease that manifests as ARDS, with fever, shortness of breath, tachypnea, hypoxemia, and diffuse pulmonary infiltrates.

- skin lesions, usually asymptomatic, can be verrucous (wart-like) or ulcerated with small pustules at the margins.

- bone lytic lesions can cause bone or joint pain.

- prostatitis may be asymptomatic or may cause pain on urinating.

- laryngeal involvement causes hoarseness.

- 40% immunocompromised individuals have CNS involvement and present as brain abscess, epidural abscess or meningitis.

Nodular skin lesions of blastomycosis

Nodular skin lesions of blastomycosis Nodular skin lesions of blastomycosis

Nodular skin lesions of blastomycosis

Cause

Blastomycosis is caused by the Blastomyces dermatitidis,[13] a member of the phylum Ascomycota in the family Ajellomycetaceae. It has been recognised as the asexual state of Ajellomyces dermatitidis.

In endemic areas, the fungus lives in soil and rotten wood near lakes and rivers.[13] Although it has never been directly observed growing in nature, it is thought to grow there as a cottony white mold, similar to the growth seen in artificial culture at 25 °C. The moist, acidic soil in the surrounding woodland harbors the fungus.

Spectrum of disease

Blastomycosis is primarily a lung infection in about 70% of cases.[14] The onset is relatively slow and symptoms are suggestive of pneumonia, often leading to initial treatment with antibacterials. Occasionally, if a lesion is seen on X-ray in a cigarette smoker, the disease may be misdiagnosed as carcinoma, leading to swift excision of the pulmonary lobe involved. Upper lung lobes are involved somewhat more frequently than lower lobes.[14] If untreated, many cases progress over a period of months to years to become disseminated blastomycosis. In these cases, the large Blastomyces yeast cells translocate from the lungs and are trapped in capillary beds elsewhere in the body, where they cause lesions. The skin is the most common organ affected, being the site of lesions in approximately 60% of cases.[14] The signature image of blastomycosis in textbooks is the indolent, verrucous or ulcerated dermal lesion seen in disseminated disease. Osteomyelitis is also common (12–60% of cases). Other recurring sites of dissemination are the genitourinary tract (kidney, prostate, epididymis; collectively ca. 25% of cases) and the brain (3–10% of cases).[14]

An uncommon but very dangerous type of primary blastomycosis manifests as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS); for example, this was seen in 9 of 72 blastomycosis cases studied in northeast Tennessee.[15] Such cases may follow massive exposure, e.g., during brush clearing operations. The fatality rate in the ARDS cases in the Tennessee study was 89%, while in non-ARDS cases of pulmonary blastomycosis, the fatality rate was 10%.

Pathogenesis

Inhaled conidia of B. dermatitidis are phagocytosed by neutrophils and macrophages in alveoli. Some of these escape phagocytosis and transform into yeast phase rapidly. Having thick walls, these are resistant to phagocytosis and express glycoprotein, BAD-1, which is a virulence factor as well as an epitope. In lung tissue, they multiply and may disseminate through blood and lymphatics to other organs, including the skin, bone, genitourinary tract, and brain. The incubation period is 30 to 100 days, although infection can be asymptomatic.

Diagnosis

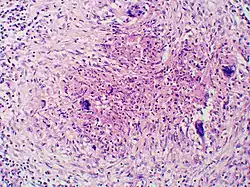

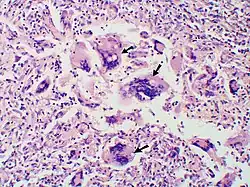

Once suspected, the diagnosis of blastomycosis can usually be confirmed by demonstration of the characteristic broad based budding organisms in sputum or tissues by KOH prep, cytology, or histology.[16] Tissue biopsy of skin or other organs may be required in order to diagnose extra-pulmonary disease. Blastomycosis is histologically associated with granulomatous nodules. Commercially available urine antigen testing appears to be quite sensitive in suggesting the diagnosis in cases where the organism is not readily detected. While culture of the organism remains the definitive diagnostic standard, its slow growing nature can lead to delays in treatment of up to several weeks. However, sometimes blood and sputum cultures may not detect blastomycosis.[17]

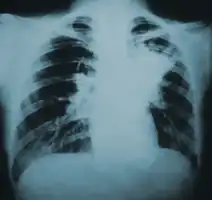

Chest X-ray

Chest X-ray Granuloma with early suppuration. Fungal organisms difficult to recognize at this low magnification.

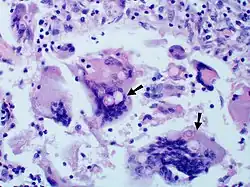

Granuloma with early suppuration. Fungal organisms difficult to recognize at this low magnification. Large yeast-like fungi seen within giant cells at arrows.

Large yeast-like fungi seen within giant cells at arrows. Large yeast-like fungi seen within giant cells at arrows.Budding yeasts in cytoplasm of giant cells at arrows. Broad-based budding and double contoured cell wall seen in the giant cell in the center is characteristic of Blastomyces dermatitidis.

Large yeast-like fungi seen within giant cells at arrows.Budding yeasts in cytoplasm of giant cells at arrows. Broad-based budding and double contoured cell wall seen in the giant cell in the center is characteristic of Blastomyces dermatitidis.

Treatment

Itraconazole given orally is the treatment of choice for most forms of the disease.[3] Ketoconazole may also be used. Cure rates are high, and the treatment over a period of months is usually well tolerated. Amphotericin B is considerably more toxic, and is usually reserved for immunocompromised patients who are critically ill and those with central nervous system disease. Those who cannot tolerate deoxycholate formulation of Amphotericin B can be given lipid formulations. Fluconazole has excellent CNS penetration and is useful where there is CNS involvement after initial treatment with Amphotericin B.

Prognosis

Mortality rate in treated cases

- 0-2% in treated cases among immunocompetent patients

- 29% in immunocompromised patients

- 40% in the subgroup of patients with AIDS

- 68% in patients presenting as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

Epidemiology

Incidences in most endemic areas are circa 0.5 per 100,000 population, with occasional local areas attaining as high as 12 per 100,000.[14][25][26][27] Most Canadian data fit this picture. In Ontario, Canada, considering both endemic and non-endemic areas, the overall incidence is around 0.3 cases per 100,000; northern Ontario, mostly endemic, has 2.44 per 100,000.[22] Manitoba is calculated at 0.62 cases per 100,000.[18] Remarkably higher incidences were shown for the Kenora, Ontario region: 117 per 100,000 overall, with aboriginal reserve communities experiencing 404.9 per 100,000.[19] In the United States, the incidence of blastomycosis is similarly high in hyperendemic areas. For example, the city of Eagle River, Vilas County, Wisconsin, which has an incidence rate of 101.3 per 100,000; the county as a whole has been shown in two successive studies to have an incidence of ca. 40 cases per 100,000.[28] An incidence of 277 per 100,000 was roughly calculated based on 9 cases seen in a Wisconsin aboriginal reservation during a time in which extensive excavation was done for new housing construction.[29] The new case rates are greater in northern states such as Wisconsin, where from 1986 to 1995 there were 1.4 cases per 100,000 people.[30]

The study of outbreaks as well as trends in individual cases of blastomycosis has clarified a number of important matters. Some of these relate to the ongoing effort to understand the source of infectious inoculum of this species, while others relate to which groups of people are especially likely to become infected. Human blastomycosis is primarily associated with forested areas and open watersheds;[14][31][32][33] It primarily affects otherwise healthy, vigorous people, mostly middle-aged,[34] who acquire the disease while working or undertaking recreational activities in sites conventionally considered clean, healthy and in many cases beautiful.[14][25] Repeatedly associated activities include hunting, especially raccoon hunting,[35] where accompanying dogs also tend to be affected, as well as working with wood or plant material in forested or riparian areas,[14][36] involvement in forestry in highly endemic areas,[37] excavation,[28] fishing[34][38] and possibly gardening and trapping.[19][28]

Urban infections

There is also a developing profile of urban and other domestic blastomycosis cases, beginning with an outbreak tentatively attributed to construction dust in Westmont, Illinois.[39] The city of Rockford, Illinois, was also documented as a hyperendemic area based on incidence rates as high as 6.67 per 100,000 population for some areas of the city. Though proximity to open watersheds was linked to incidence in some areas,[33] suggesting that outdoor activity within the city may be connected to many cases, there is also an increasing body of evidence that even the interiors of buildings may be risk areas. An early case concerned a prisoner who was confined to prison during the whole of his likely blastomycotic incubation period.[40] An epidemiological survey found that although many patients who contracted blastomycosis had engaged in fishing, hunting, gardening, outdoor work and excavation, the most strongly linked association in patients was living or visiting near waterways.[38] Based on a similar finding in a Louisiana study, it has been suggested that place of residence might be the most important single factor in blastomycosis epidemiology in north central Wisconsin.[41] Follow-up epidemiological and case studies indicated that clusters of cases were often associated with particular domiciles, often spread out over a period of years, and that there were uncommon but regularly occurring cases in which pets kept mostly or entirely indoors, in particular cats, contracted blastomycosis.[42][43] The occurrence of blastomycosis, then, is an issue strongly linked to housing and domestic circumstances.

Seasonal trends

Seasonality and weather also appear to be linked to contraction of blastomycosis. Many studies have suggested an association between blastomycosis contraction and cool to moderately warm, moist periods of the spring and autumn[14][19][44] or, in relatively warm winter areas.[45] However, the entire summer or a known summer exposure date is included in the association in some studies.[34][46] Occasional studies fail to detect a seasonal link.[47] In terms of weather, both unusually dry weather[48] and unusually moist weather[49] have been cited. The seemingly contradictory data can most likely be reconciled by proposing that B. dermatitidis prospers in its natural habitats in times of moisture and moderate warmth, but that inoculum formed during these periods remains alive for some time and can be released into the air by subsequent dust formation under dry conditions. Indeed, dust per se or construction potentially linked to dust has been associated with several outbreaks[15][39][50] The data, then, tend to link blastomycosis to all weather, climate and atmospheric conditions except freezing weather, periods of snow cover, and extended periods of hot, dry summer weather in which soil is not agitated.

Gender bias

Sex is another factor inconstantly linked to contraction of blastomycosis: though many studies show more men than women affected,[14][22] some show no sex-related bias.[19][38] As mentioned above, most cases are in middle aged adults, but all age groups are affected, and cases in children are not uncommon.[14][19][22]

Ethnic populations

Ethnic group or race is frequently investigated in epidemiological studies of blastomycosis, but is potentially profoundly conflicted by differences in residence and in quality and accessibility of medical care, factors that have not been stringently controlled for to date. In the USA, a disproportionately high incidence and/or mortality rate is occasionally shown for blacks;[26][27][51][52] whereas aboriginals in Canada are disproportionately linked to blastomycosis in some studies[19][53] but not others.[18] Incidence in aboriginal children may be unusually high.[19] The Canadian data in some areas may be confounded or explained by the tendency to establish aboriginal communities in wooded, riparian, northern areas corresponding to the core habitat of B. dermatitidis, often with known B. dermatitidis habitats such as woodpiles and beaver constructions in the near vicinity.

Communicability

There are a very small number of cases of human-to-human transmission of B. dermatitidis related to dermal contact[54] or sexual transmission of disseminated blastomycosis of the genital tract among spouses.[14]

History

Blastomycosis was first described by Thomas Casper Gilchrist in 1894; because of this, it is sometimes called "Gilchrist's disease".[12] It is also sometimes referred to as Chicago Disease. Other names for blastomycosis include North American blastomycosis, and blastomycetic dermatitis.[55]

Among a skeletal series of Late Woodland Native Americans and later burial populations (the Mississippians, AD 900-1673) Dr. Jane Buikstra found evidence for what may have been an epidemic of a serious spinal disease in adolescents and young adults. Several of the skeletons showed lesions in the spinal vertebrae in the lower back. There are two modern diseases that produce lesions in the bone similar to the ones Dr. Buikstra found in these prehistoric specimens - spinal TB and blastomycosis. The bony lesions in these two diseases are practically identical. Blastomycosis seems more probable as these young people in Late Woodland and Mississippian times may have been afflicted because they were spending more time cultivating plants than their Middle Woodland predecessors had done. If true, it would be another severe penalty Late Woodland people had to pay as they shifted to agriculture as a way of life, and it would be a contributing factor to shortening their lifespans compared to those of the Middle Woodland people.[56]

Other animals

Blastomycosis also affects an indefinitely broad range of mammalian hosts, and dogs in particular are a highly vulnerable sentinel species.[14] The disease generally begins with acute respiratory symptoms and rapidly progresses to death. Cats are the animals next most frequently detected as infected.[42]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Johnstone, Ronald B. (2017). "25. Mycoses and Algal infections". Weedon's Skin Pathology Essentials (2nd ed.). Elsevier. p. 449. ISBN 978-0-7020-6830-0. Archived from the original on 2023-06-30. Retrieved 2023-06-20.

- 1 2 3 "Symptoms of Blastomycosis". cdc.gov. 2019-01-29. Archived from the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- 1 2 3 Barlow, Gavin; Irving, Irving; moss, Peter J. (2020). "20. Infectious diseases". In Feather, Adam; Randall, David; Waterhouse, Mona (eds.). Kumar and Clark's Clinical Medicine (10th ed.). Elsevier. p. 561. ISBN 978-0-7020-7870-5. Archived from the original on 2021-06-13. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

- ↑ "ICD-11 - ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics". icd.who.int. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved 29 May 2021.

- 1 2 Murray P, Rosenthal K, Pfaller M (2015). "Chapter 64: Systemic Mycoses Caused by Dimorphic Fungi". Medical Microbiology (8 ed.). Elsevier. pp. 629–633. ISBN 978-0323299565.

- ↑ "Blastomycosis". cdc.gov. 2019-01-24. Archived from the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- 1 2 3 "Information for Healthcare Professionals about Blastomycosis". cdc.gov. 2019-01-24. Archived from the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- 1 2 "Blastomycosis Risk & Prevention". cdc.gov. 2019-01-29. Archived from the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- ↑ "Treatment for Blastomycosis". cdc.gov. 2019-01-29. Archived from the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- ↑ Castillo CG, Kauffman CA, Miceli MH (March 2016). "Blastomycosis". Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 30 (1): 247–64. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2015.10.002. PMID 26739607.

- ↑ "Blastomycosis Statistics". cdc.gov. 2019-01-24. Archived from the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- 1 2 Crissey, John Thorne; Parish, Lawrence C.; Holubar, Karl (2002). Historical Atlas of Dermatology and Dermatologists. Parthenon Publishing Group. p. 86. ISBN 978-1842141007. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-05-29.

- 1 2 "Sources of Blastomycosis". cdc.gov. 2019-01-29. Archived from the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Kwon-Chung, K.J., Bennett, J.E.; Bennett, John E. (1992). Medical mycology. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger. ISBN 978-0812114638.

- 1 2 Vasquez, JE; Mehta, JB; Agrawal, R; Sarubbi, FA (1998). "Blastomycosis in northeast Tennessee". Chest. 114 (2): 436–43. doi:10.1378/chest.114.2.436. PMID 9726727.

- ↑ Veligandla SR, Hinrichs SH, Rupp ME, Lien EA, Neff JR, Iwen PC (October 2002). "Delayed diagnosis of osseous blastomycosis in two patients following environmental exposure in nonendemic areas". Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 118 (4): 536–41. doi:10.1309/JEJ0-3N98-C3G8-21DE. PMID 12375640.

- ↑ Morgan, Matthew W; Salit, Irving E (1996). "Human and canine blastomycosis: A common source infection". The Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 7 (2): 147–151. doi:10.1155/1996/657941. ISSN 1180-2332. PMC 3327387. PMID 22514432.

- 1 2 3 Crampton, TL; Light, RB; Berg, GM; Meyers, MP; Schroeder, GC; Hershfield, ES; Embil, JM (2002). "Epidemiology and clinical spectrum of blastomycosis diagnosed at Manitoba hospitals". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 34 (10): 1310–6. doi:10.1086/340049. PMID 11981725.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Dwight, P.J.; Naus, M; Sarsfield, P; Limerick, B (2000). "An outbreak of human blastomycosis: the epidemiology of blastomycosis in the Kenora catchment region of Ontario, Canada". Canada Communicable Disease Report. 26 (10): 82–91. PMID 10893821.

- ↑ Kane, J; Righter, J; Krajden, S; Lester, RS (1983). "Blastomycosis: a new endemic focus in Canada". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 129 (7): 728–31. PMC 1875443. PMID 6616383.

- ↑ Lester, RS; DeKoven, JG; Kane, J; Simor, AE; Krajden, S; Summerbell, RC (2000). "Novel cases of blastomycosis acquired in Toronto, Ontario". CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association Journal. 163 (10): 1309–12. PMC 80342. PMID 11107469.

- 1 2 3 4 Morris, SK; Brophy, J; Richardson, SE; Summerbell, R; Parkin, PC; Jamieson, F; Limerick, B; Wiebe, L; Ford-Jones, EL (2006). "Blastomycosis in Ontario, 1994-2003". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 12 (2): 274–9. doi:10.3201/eid1202.050849. PMC 3373107. PMID 16494754.

- ↑ Sekhon, AS; Jackson, FL; Jacobs, HJ (1982). "Blastomycosis: report of the first case from Alberta Canada". Mycopathologia. 79 (2): 65–9. doi:10.1007/bf00468081. PMID 6813742. S2CID 27296444.

- ↑ Vallabh, V; Martin, T; Conly, JM (1988). "Blastomycosis in Saskatchewan". The Western Journal of Medicine. 148 (4): 460–2. PMC 1026149. PMID 3388850.

- 1 2 Rippon, John Willard (1988). Medical mycology : the pathogenic fungi and the pathogenic actinomycetes (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co. ISBN 9780721624440.

- 1 2 Manetti, AC (1991). "Hyperendemic urban blastomycosis". American Journal of Public Health. 81 (5): 633–6. doi:10.2105/ajph.81.5.633. PMC 1405080. PMID 2014867.

- 1 2 Cano, MV; Ponce-de-Leon, GF; Tippen, S; Lindsley, MD; Warwick, M; Hajjeh, RA (2003). "Blastomycosis in Missouri: epidemiology and risk factors for endemic disease". Epidemiology and Infection. 131 (2): 907–14. doi:10.1017/s0950268803008987. PMC 2870035. PMID 14596532.

- 1 2 3 Baumgardner, DJ; Brockman, K (1998). "Epidemiology of human blastomycosis in Vilas County, Wisconsin. II: 1991-1996". WMJ. 97 (5): 44–7. PMID 9617309.

- ↑ Baumgardner, DJ; Egan, G; Giles, S; Laundre, B (2002). "An outbreak of blastomycosis on a United States Indian reservation". Wilderness & Environmental Medicine. 13 (4): 250–2. doi:10.1580/1080-6032(2002)013[0250:aooboa]2.0.co;2. PMID 12510781.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (1996). "Blastomycosis--Wisconsin, 1986-1995". MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 45 (28): 601–3. PMID 8676851.

- ↑ DiSalvo, A.F. (1992). Al-Doory, Y.; DiSalvo, A.F. (eds.). Ecology of Blastomyces dermatitidis. Plenum. pp. 43–73.

- ↑ Baumgardner, DJ; Steber, D; Glazier, R; Paretsky, DP; Egan, G; Baumgardner, AM; Prigge, D (2005). "Geographic information system analysis of blastomycosis in northern Wisconsin, USA: waterways and soil". Medical Mycology. 43 (2): 117–25. doi:10.1080/13693780410001731529. PMID 15832555.

- 1 2 Baumgardner, DJ; Knavel, EM; Steber, D; Swain, GR (2006). "Geographic distribution of human blastomycosis cases in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA: association with urban watersheds". Mycopathologia. 161 (5): 275–82. doi:10.1007/s11046-006-0018-9. PMID 16649077. S2CID 7953521.

- 1 2 3 Klein, Bruce S.; Vergeront, James M.; Weeks, Robert J.; Kumar, U. Nanda; Mathai, George; Varkey, Basil; Kaufman, Leo; Bradsher, Robert W.; Stoebig, James F.; Davis, Jeffrey P. (1986). "Isolation of Blastomyces dermatitidis in Soil Associated with a Large Outbreak of Blastomycosis in Wisconsin". New England Journal of Medicine. 314 (9): 529–534. doi:10.1056/NEJM198602273140901. PMID 3945290.

- ↑ Armstrong, CW; Jenkins, SR; Kaufman, L; Kerkering, TM; Rouse, BS; Miller GB, Jr (1987). "Common-source outbreak of blastomycosis in hunters and their dogs". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 155 (3): 568–70. doi:10.1093/infdis/155.3.568. PMID 3805778.

- ↑ Kesselman, EW; Moore, S; Embil, JM (2005). "Using local epidemiology to make a difficult diagnosis: a case of blastomycosis". CJEM. 7 (3): 171–3. doi:10.1017/S1481803500013221. PMID 17355674.

- ↑ Vaaler, AK; Bradsher, RW; Davies, SF (1990). "Evidence of subclinical blastomycosis in forestry workers in northern Minnesota and northern Wisconsin". The American Journal of Medicine. 89 (4): 470–6. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(90)90378-q. PMID 2220880.

- 1 2 3 Baumgardner, DJ; Buggy, BP; Mattson, BJ; Burdick, JS; Ludwig, D (1992). "Epidemiology of blastomycosis in a region of high endemicity in north central Wisconsin". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 15 (4): 629–35. doi:10.1093/clind/15.4.629. PMID 1420675.

- 1 2 Kitchen, MS; Reiber, CD; Eastin, GB (1977). "An urban epidemic of North American blastomycosis". The American Review of Respiratory Disease. 115 (6): 1063–6. doi:10.1164/arrd.1977.115.6.1063 (inactive 2021-01-14). PMID 262101. Archived from the original on 2021-09-23. Retrieved 2021-05-29.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2021 (link) - ↑ Renston, JP; Morgan, J; DiMarco, AF (1992). "Disseminated miliary blastomycosis leading to acute respiratory failure in an urban setting". Chest. 101 (5): 1463–5. doi:10.1378/chest.101.5.1463. PMID 1582324.

- ↑ Lowry, PW; Kelso, KY; McFarland, LM (1989). "Blastomycosis in Washington Parish, Louisiana, 1976-1985". American Journal of Epidemiology. 130 (1): 151–9. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115307. PMID 2787106.

- 1 2 Blondin, N; Baumgardner, DJ; Moore, GE; Glickman, LT (2007). "Blastomycosis in indoor cats: suburban Chicago, Illinois, USA". Mycopathologia. 163 (2): 59–66. doi:10.1007/s11046-006-0090-1. PMID 17262169. S2CID 1227756.

- ↑ Baumgardner, DJ; Paretsky, DP (2001). "Blastomycosis: more evidence for exposure near one's domicile". WMJ. 100 (7): 43–5. PMID 11816782.

- ↑ Rudmann, DG; Coolman, BR; Perez, CM; Glickman, LT (1992). "Evaluation of risk factors for blastomycosis in dogs: 857 cases (1980-1990)". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 201 (11): 1754–9. PMID 1293122.

- ↑ Arceneaux, KA; Taboada, J; Hosgood, G (1998). "Blastomycosis in dogs: 115 cases (1980-1995)". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 213 (5): 658–64. PMID 9731260.

- ↑ Archer, JR; Trainer, DO; Schell, RF (1987). "Epidemiologic study of canine blastomycosis in Wisconsin". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 190 (10): 1292–5. PMID 3583882.

- ↑ Chapman, SW; Lin, AC; Hendricks, KA; Nolan, RL; Currier, MM; Morris, KR; Turner, HR (1997). "Endemic blastomycosis in Mississippi: epidemiological and clinical studies". Seminars in Respiratory Infections. 12 (3): 219–28. PMID 9313293.

- ↑ Proctor, ME; Klein, BS; Jones, JM; Davis, JP (2002). "Cluster of pulmonary blastomycosis in a rural community: evidence for multiple high-risk environmental foci following a sustained period of diminished precipitation". Mycopathologia. 153 (3): 113–20. doi:10.1023/A:1014515230994. PMID 11998870. S2CID 38668503.

- ↑ De Groote, MA; Bjerke, R; Smith, H; Rhodes III, LV (2000). "Expanding epidemiology of blastomycosis: clinical features and investigation of 2 cases in Colorado". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 30 (3): 582–4. doi:10.1086/313717. PMID 10722448.

- ↑ Baumgardner, DJ; Burdick, JS (1991). "An outbreak of human and canine blastomycosis". Reviews of Infectious Diseases. 13 (5): 898–905. doi:10.1093/clinids/13.5.898. PMID 1962106.

- ↑ Dworkin, MS; Duckro, AN; Proia, L; Semel, JD; Huhn, G (2005). "The epidemiology of blastomycosis in Illinois and factors associated with death". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 41 (12): e107–11. doi:10.1086/498152. PMID 16288388.

- ↑ Lemos, LB; Guo, M; Baliga, M (2000). "Blastomycosis: organ involvement and etiologic diagnosis. A review of 123 patients from Mississippi". Annals of Diagnostic Pathology. 4 (6): 391–406. doi:10.1053/adpa.2000.20755. PMID 11149972.

- ↑ Kepron, MW; Schoemperlen; Hershfield, ES; Zylak, CJ; Cherniack, RM (1972). "North American blastomycosis in Central Canada. A review of 36 cases". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 106 (3): 243–6. PMC 1940364. PMID 5057959.

- ↑ Bachir, J; Fitch, GL (2006). "Northern Wisconsin married couple infected with blastomycosis". WMJ. 105 (6): 55–7. PMID 17042422.

- ↑ James, William D.; Berger, Timothy G.; et al. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. p. 319. ISBN 978-0-7216-2921-6.

- ↑ Struever, Stuart and Felicia Antonelli Holton (1979). Koster: Americans in Search of Their Prehistoric Past. New York: Anchor Press / Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-00406-0.

Further reading

- Castillo CG, Kauffman CA, Miceli MH (2016). "Blastomycosis". Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 30 (1): 247–264. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2015.10.002. PMID 26739607. (Review).

- McBride JA, Gauthier GM, Klein BS (2017). "Clinical Manifestations and Treatment of Blastomycosis". Clinics in Chest Medicine. 38 (3): 435–449. doi:10.1016/j.ccm.2017.04.006. PMC 5657236. PMID 28797487. PMC 5657236 (Review)

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Blastomyces at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- NIH Encyclopedia Blastomycosis Archived 2021-08-28 at the Wayback Machine