Itraconazole

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Sporanox, Sporaz, Orungal, others |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Antifungal (triazole)[1] |

| Main uses | Tinea capitis, histoplasmosis, penicilliosis[2] |

| Side effects | Nausea, diarrhea, abdominal pain, rash, headache[1] |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of use | By mouth (capsules, solution), local (vaginal suppository), intravenous (IV) |

| Defined daily dose | 200 mg[4] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a692049 |

| Legal | |

| License data |

|

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | ~55%, maximal if taken with full meal |

| Protein binding | 99.8% |

| Metabolism | Extensive in liver (CYP3A4) |

| Metabolites | Hydroxy-itraconazole, keto-itraconazole, N-desalkyl-itraconazole[6] |

| Elimination half-life | 21 hours |

| Excretion | Urine (35%), faeces (54%)[7] |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C35H38Cl2N8O4 |

| Molar mass | 705.64 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Itraconazole is an antifungal medication used to treat a number of fungal infections.[1] This includes aspergillosis, blastomycosis, coccidioidomycosis, histoplasmosis, and paracoccidioidomycosis.[1] It may be given by mouth or intravenously.[1]

Common side effects include nausea, diarrhea, abdominal pain, rash, and headache.[1] Severe side effects may include liver problems, heart failure, Stevens–Johnson syndrome and allergic reactions including anaphylaxis.[1] It is unclear if use during pregnancy or breastfeeding is safe.[3] It is in the triazole family of medications.[1] It stops fungal growth by affecting the cell membrane or affecting their metabolism.[1]

Itraconazole was patented in 1978 and approved for medical use in the United States in 1992.[1][8] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[9] The wholesale cost in the developing world is about US$0.29 per day of treatment as of 2015.[10] In the United States, as of 2021, the wholesale cost of this dose is $2.[11] In the UK, as of 2020, 15 capsules of 100mg itraconazole costs the NHS £3.55.[12]

Medical uses

Itraconazole has a broader spectrum of activity than fluconazole (but not as broad as voriconazole or posaconazole). In particular, it is active against Aspergillus, which fluconazole is not. It is also licensed for use in blastomycosis, sporotrichosis, histoplasmosis, and onychomycosis. Itraconazole is over 99% protein-bound and has virtually no penetration into cerebrospinal fluid. Therefore, it should not be used to treat meningitis or other central nervous system infections.[13] According to the Johns Hopkins Abx Guide, it has "negligible CSF penetration, however treatment has been successful for cryptococcal and coccidioidal meningitis".[14]

It is also prescribed for systemic infections, such as aspergillosis, candidiasis, where other antifungal drugs are inappropriate or ineffective.[15]

Itraconazole has also recently been explored as an anticancer agent for patients with basal cell carcinoma, non-small cell lung cancer, and prostate cancer.[16] For example, in a phase II study involving men with advanced prostate cancer, high-dose itraconazole (600 mg/day) was associated with significant PSA responses and a delay in tumor progression. Itraconazole also showed activity in a phase II trial in men with non-small cell lung cancer when it was combined with the chemotherapy agent, pemetrexed.[17][18][19]

Dosage

The defined daily dose is 200 mg either by mouth or by injection.[4] For tinea capitis the dose in adults is 200 mg once per day for two to four weeks while the dose is children is 3 to 5 mg/kg daily for 4 weeks.[2] Doses of 200 mg three times per day for three days, followed by 200 mg either one to twice per day for up to 12 weeks may be used for histoplasmosis.[2] The dose is in children is 5 mg/kg.[2] Penicilliosis is treated with 200 mg twice per day for eight weeks.[2]

Available forms

Itraconazole is produced as blue 22 mm (0.87 in) capsules with tiny 1.5 mm (0.059 in) blue pellets inside. Each capsule contains 100 mg and is usually taken twice a day at twelve-hour intervals. The Sporanox brand of itraconazole has been developed and marketed by Janssen Pharmaceutica, a subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson. The three-layer structure of these blue capsules is complex because itraconazole is insoluble and is sensitive to pH. The complicated procedure not only requires a specialized machine to create it, but also the method used has manufacturing problems. Also, the pill is quite large, making it difficult for many patients to swallow. Parts of the processes of creating Sporanox were discovered by the Korean Patent Laid-open No. 10-2001-2590.[20] The tiny blue pellets contained in the capsule are manufactured in Beerse, Belgium.[20][21]

The oral solution is better absorbed. The cyclodextrin contained in the oral solution can cause an osmotic diarrhea, and if this is a problem, then half the dose can be given as oral solution and half as capsule to reduce the amount of cyclodextrin given. "Sporanox" itraconazole capsules should always be taken with food, as this improves absorption, however the manufacturers of "Lozanoc" assert that it may be taken "without regard to meals".[22] Itraconazole oral solution should be taken an hour before food, or two hours after food (and likewise if a combination of capsules and oral solution are used). Itraconazole may be taken with non-diet cola, which may improve absorption in people who have less stomach acid.[23]

Side effects

.jpg.webp)

Itraconazole is a relatively well-tolerated drug (although not as well tolerated as fluconazole or voriconazole) and the range of adverse effects it produces is similar to the other azole antifungals:[24]

- elevated alanine aminotransferase levels are found in 2-3% of people taking itraconazole[25]

- "small but real risk" of developing congestive heart failure[24]

- liver failure[25]

Side effects that may indicate a greater problem and therefore the need to seek medical attention include:[26]

Interactions

The following drugs should not be taken with itraconazole:[27]

- amiodarone

- cisapride

- dofetilide

- nisoldipine

- pimozide

- quinidine

- lurasidone

- lovastatin

- midazolam

- ergot medicines such as

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

The mechanism of action of itraconazole is the same as the other azole antifungals: it inhibits the fungal-mediated synthesis of ergosterol, via inhibition of lanosterol 14α-demethylase. Because of its ability to inhibit cytochrome P450 3A4 CC-3, caution should be used when considering interactions with other medications.[28]

Itraconazole is pharmacologically distinct from other azole antifungal agents in that it is the only inhibitor in this class that has been shown to inhibit both the hedgehog signaling pathway and angiogenesis.[29][30] Functionally, the antiangiogenic activity of itraconazole has been shown to be linked to inhibition of glycosylation, VEGFR2 phosphorylation, trafficking,[31] and cholesterol biosynthesis pathways.[29] Evidence suggests the structural determinants for inhibition of hedgehog signaling by itraconazole are recognizably different from those associated with antiangiogenic activity.[32]

Pharmacokinetics

Itraconazole, can inhibit P-glycoprotein, causing drug interactions by reducing elimination and increasing absorption of organic cation drugs. With conventional itraconazole preparations serum levels can vary greatly between patients, often resulting in serum concentrations lower than the therapeutic index. It has therefore been conventionally advised that patients take itraconazole after a fatty meal rather than prior to eating.[33]A product (Lozanoc) licensed through the European union decentralised procedure has increased bioavailability, decreased sensitivity to co ingestion of food, and hence decreased variability of serum levels.[34]

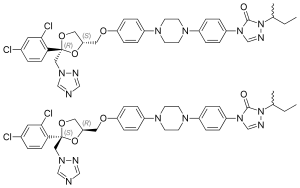

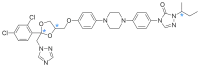

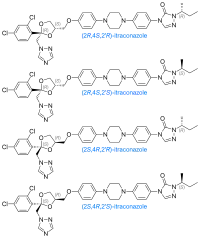

Chemistry

Itraconazole molecule has three chiral carbons. The two chiral centers in the dioxolane ring are fixed in relation to one another, and the triazolomethylene and aryloxymethylene dioxolane-ring substituents are always cis to each other. The clinical formulation is a 1:1:1:1 mixture of four stereoisomers (two enantiomeric pairs).[35][36][37]

History

Itraconazole was patented in 1978 and approved for medical use in the United States in 1992.[1][38] Prior to its development, amphotericin B and ketoconazole were the main drugs for treating systemic fungal infections.[39] In 2016 Itraconazole was designated an orphan drug by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in 2018.[40][41]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Itraconazole". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "ITRACONAZOLE oral - Essential drugs". medicalguidelines.msf.org. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- 1 2 3 "Itraconazole Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 20 March 2019. Archived from the original on 10 April 2020. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- 1 2 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ↑ "Sporanox 10 mg/ml Oral Solution - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 1 February 2018. Archived from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ↑ Isoherranen, N; Kunze, KL; Allen, KE; Nelson, WL; Thummel, KE (October 2004). "Role of Itraconazole Metabolites in CYP3A4 Inhibition". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 32 (10): 1121–31. doi:10.1124/dmd.104.000315. PMID 15242978.

- ↑ "Sporanox (itraconazole) Capsules. Full Prescribing Information" (PDF). Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 May 2018. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- ↑ Fischer, Jnos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 503. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 2020-08-02. Retrieved 2021-01-22.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ "Single Drug Information". International Medical Products Price Guide. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- ↑ "NADAC (National Average Drug Acquisition Cost) | Data.Medicaid.gov". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ↑ BNF (80 ed.). BMJ Group and the Pharmaceutical Press. September 2020 – March 2021. p. 632-633. ISBN 978-0-85711-369-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ↑ Gilbert DN, Moellering, RC, Eliopoulos GM, Sande MA (2006). The Sanford Guide to antimicrobial therapy. ISBN 978-1-930808-30-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)pp. 153-54 - ↑ Pham, P; Bartlett, JG (2007-07-24). "Itraconazole". Johns Hopkins. Archived from the original on 2007-11-28.

- ↑ McKeny, Patrick T.; Nessel, Trevor A.; Zito, Patrick M. (2020). "Antifungal Antibiotics". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 13 November 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ↑ "Clinical trials results for Itraconazole". ClinicalTrials.gov. U.S. National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 2013-04-28. Retrieved 2011-10-11.

- ↑ Aftab BT, Dobromilskaya I, Liu JO, Rudin CM (2011). "Itraconazole inhibits angiogenesis and tumor growth in non-small cell lung cancer". Cancer Research. 71 (21): 6764–6772. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0691. PMC 3206167. PMID 21896639.

- ↑ Antonarakis ES, Heath EI, Smith DC, Rathkopf D, Blackford AL, Danila DC, King S, Frost A, Ajiboye AS, Zhao M, Mendonca J, Kachhap SK, Rudek MA, Carducci MA (2013). "Repurposing itraconazole as a treatment for advanced prostate cancer: a noncomparative randomized phase II trial in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer". The Oncologist. 18 (2): 163–173. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2012-314. PMC 3579600. PMID 23340005.

- ↑ Rudin CM, Brahmer JR, Juergens RA, Hann CL, Ettinger DS, Sebree R, Smith R, Aftab BT, Huang P, Liu JO (May 2013). "Phase 2 study of pemetrexed and itraconazole as second-line therapy for metastatic nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer". Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 8 (5): 619–623. doi:10.1097/JTO.0b013e31828c3950. PMC 3636564. PMID 23546045.

- 1 2 Composition comprising Itraconazole for oral administration Archived 2007-02-26 at the Wayback Machine. 2004. Fresh Patents.com. 26 October 2006.

- ↑ Sporanox (Itraconazole Capsules) Archived 2008-07-05 at the Wayback Machine. June 2006. Janssen. 26 October 2006

- ↑ "SUBA Bioavailability Technology". Mayne Pharma Group. Archived from the original on 2014-05-25. Retrieved 2014-05-25.

- ↑ "Itraconazole Dosage Guide with Precautions". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 27 April 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- 1 2 "The Safety of Sporanox Capsules and Lamisil Tablets for the Treatment of Onychomycosis". FDA Public Health Advisory. May 9, 2001. Archived from the original on 2009-05-28. Retrieved 2006-08-10.

- 1 2 "Itraconazole". LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. 2012. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ↑ "Itraconazole: MedlinePlus Drug Information". medlineplus.gov. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ↑ "Itraconazole Drug Interactions". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 22 May 2016. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ↑ Katzung & Trevor's (2015). Pharmacology Examination & Board Review. McGraw Hill. p. 397.

- 1 2 Chong CR, Xu J, Lu J, Bhat S, Sullivan DJ, Liu JO (2007). "Inhibition of Angiogenesis by the Antifungal Drug Itraconazole". ACS Chemical Biology. 2 (4): 263–70. doi:10.1021/cb600362d. PMID 17432820.

- ↑ Tsai, Ya-Chu; Tsai, Tsen-Fang (30 April 2019). "Itraconazole in the Treatment of Nonfungal Cutaneous Diseases: A Review". Dermatology and Therapy. 9 (2): 271–280. doi:10.1007/s13555-019-0299-9. ISSN 2193-8210. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ↑ Saxena, Anil Kumar. Communicable Diseases of the Developing World. Springer. p. 136. ISBN 978-3-319-78254-6. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ↑ "Itraconazole". www.chemsrc.com. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ↑ Domínguez-Gil Hurlé, A.; Sánchez Navarro, A.; García Sánchez, M.J. (December 2006). "Therapeutic drug monitoring of itraconazole and the relevance of pharmacokinetic interactions". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 12: 97–106. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01611.x. ISSN 1198-743X. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ↑ "Lozanoc 50 Mg Hard Capsules (Itraconazole)" (PDF). Public Assessment Report Decentralised Procedure. UK Medicines and Health Care Products Regulatory Agency. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-05-25. Retrieved 2014-05-25.

- ↑ "Itraconazole | C35H38Cl2N8O4 | ChemSpider". www.chemspider.com. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ↑ "Itraconazole on Drugs.com". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- ↑ "Itraconazole". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ↑ "Itraconazole: FDA-Approved Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ↑ Maertens, J. A. (March 2004). "History of the development of azole derivatives". Clinical Microbiology and Infection: The Official Publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 10 Suppl 1: 1–10. doi:10.1111/j.1470-9465.2004.00841.x. ISSN 1198-743X. PMID 14748798. Archived from the original on 21 August 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ↑ "Itraconazole Orphan Drug Designation". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 16 August 2016. Archived from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ↑ "EU/3/18/2024". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 25 May 2018. Archived from the original on 8 January 2021. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

External links

| External sites: |

|

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |