Griseofulvin

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Gris-peg, Grifulvin V, others |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Antifungal |

| Main uses | Dermatophytoses (ringworm)[1] |

| Side effects | Allergic reactions, nausea, diarrhea, headache, trouble sleeping, feeling tired[1] |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth |

| Defined daily dose | 500 mg[2] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682295 |

| Legal | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | Highly variable (25 to 70%) |

| Metabolism | Liver (demethylation and glucuronidation) |

| Elimination half-life | 9–21 hours |

| Chemical and physical data | |

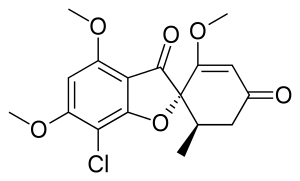

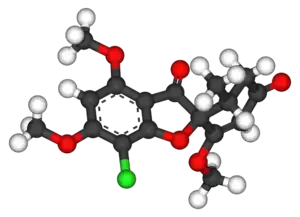

| Formula | C17H17ClO6 |

| Molar mass | 352.766 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Griseofulvin is an antifungal medication used to treat a number of types of dermatophytoses (ringworm).[1] This includes fungal infections of the nails and scalp, as well as the skin when antifungal creams have not worked.[3] It is taken by mouth.[1]

Common side effects include allergic reactions, nausea, diarrhea, headache, trouble sleeping, and feeling tired.[1] It is not recommended in people with liver failure or porphyria.[1] Use during or in the months before pregnancy may result in harm to the baby.[1][3] Griseofulvin works by interfering with fungal mitosis.[1]

Griseofulvin was discovered in 1939 from a type of Penicillium mold.[4][5] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[6] The wholesale cost in the developing world is about US$0.05–0.18 per day.[7] In the United States a course of treatment costs $100–200.[8]

Medical uses

Griseofulvin is used by mouth for dermatophytosis. It is ineffective topically. It is reserved for cases with nail, hair, or large body surface involvement.[9]

Terbinafine given for 2 to 4 weeks is at least as effective as griseofulvin given for 6 to 8 weeks for treatment of Trichophyton scalp infections. However, griseofulvin is more effective than terbinafine for treatment of Microsporum scalp infections.[10][11]

Dosage

The defined daily dose is 500 mg.[12][2] The typical dose in those over the age 12 is 500 mg once per day though 1,000 mg once per day may be used in severe infections.[13] In those aged 1 to 12 years 10 to 20 mg/kg once per day may be used.[13] The duration of treatment is generally 4 to 6 weeks.[13]

Side effects

Side effects include:

|

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

The drug binds to tubulin, interfering with microtubule function, thus inhibiting mitosis. It binds to keratin in keratin precursor cells and makes them resistant to fungal infections. The drug reaches its site of action only when hair or skin is replaced by the keratin-griseofulvin complex. Griseofulvin then enters the dermatophyte through energy-dependent transport processes and bind to fungal microtubules. This alters the processing for mitosis and also underlying information for deposition of fungal cell walls.

Biosynthetic process

It is produced industrially by fermenting the fungus Penicillium griseofulvum.[14][15][16]

The first step in the biosynthesis of griseofulvin by P. griseofulvin is the synthesis of the 14-carbon poly-β-keto chain by a type I iterative polyketide synthase (PKS) via iterative addition of 6 malonyl-CoA to an acyl-CoA starter unit. The 14-carbon poly-β-keto chain undergoes cyclization/aromatization, using cyclase/aromatase, respectively, through a Claisen and aldol condensation to form the benzophenone intermediate. The benzophenone intermediate is then methylated via S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) twice to yield griseophenone C. The griseophenone C is then halogenated at the activated site ortho to the phenol group on the left aromatic ring to form griseophenone B. The halogenated species then undergoes a single phenolic oxidation in both rings forming the two oxygen diradical species. The right oxygen radical shifts alpha to the carbonyl via resonance allowing for a stereospecific radical coupling by the oxygen radical on the left ring forming a tetrahydrofuranone species.[17] The newly formed grisan skeleton with a spiro center is then O-methylated by SAM to generate dehydrogriseofulvin. Ultimately, a stereoselective reduction of the olefin on dehydrogriseofulvin by NADPH affords griseofulvin.[18][19]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Griseofulvin". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- 1 2 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- 1 2 World Health Organization (2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. p. 149. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 9789241547659.

- ↑ Block, Seymour Stanton (2001). Disinfection, Sterilization, and Preservation. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 631. ISBN 9780683307405. Archived from the original on 2016-12-20.

- ↑ Michael Ash; Irene Ash (2004). Handbook of Preservatives. Synapse Info Resources. p. 406. ISBN 978-1-890595-66-1. Archived from the original on 2013-12-31.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ "Griseofulvin". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Archived from the original on 22 January 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 44. ISBN 9781284057560.

- ↑ Tripathi. Textbook of Pharmacology. Jaypee Brothers. pp. 761–762. ISBN 81-8448-085-7. Archived from the original on 2017-06-03.

- ↑ Fleece D, Gaughan JP, Aronoff SC (November 2004). "Griseofulvin versus terbinafine in the treatment of tinea capitis: a meta-analysis of randomized, clinical trials". Pediatrics. 114 (5): 1312–5. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-0428. PMID 15520113.

- ↑ Chen X, Jiang X, Yang M, González U, Lin X, Hua X, Xue S, Zhang M, Bennett C (May 2016). "Systemic antifungal therapy for tinea capitis in children". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (5): CD004685. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004685.pub3. PMID 27169520.

- ↑ "Single Drug Information – International Medical Products Price Guide". mshpriceguide. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- 1 2 3 "GRISEOFULVIN oral - Essential drugs". medicalguidelines.msf.org. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- ↑ Oxford, Albert Edward; Raistrick, Harold; Simonart, Paul (1 February 1939). "Studies in the biochemistry of micro-organisms: Griseofulvin, C17H17O6Cl, a metabolic product of Penicillium griseo-fulvum Dierckx". Biochemical Journal. 33 (2): 240–248. doi:10.1042/bj0330240. PMC 1264363. PMID 16746904. Archived from the original on 27 September 2018. Retrieved 26 September 2018 – via www.biochemj.org.

- ↑ J.F. Grove, D. Ismay, J. Macmillan, T.P.C. Mulholland, M.A.T. Rogers, Chem. Ind. (London), 219 (1951).

- ↑ Grove, J. F.; MacMillan, J.; Mulholland, T. P. C.; Rogers, M. A. T. (1952). "762. Griseofulvin. Part IV. Structure". Journal of the Chemical Society (Resumed): 3977. doi:10.1039/JR9520003977.

- ↑ Birch, Arthur (1953). "Studies in relation to biosynthesis I. Some possible routes to derivatives of orcinol and phloroglucinol". Australian Journal of Chemistry. 6 (4): 360. doi:10.1071/ch9530360.

- ↑ Dewick, Paul M. (2009). Medicinal Natural Products: A Biosynthetic Approach (3rd ed.). UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd. ISBN 0-471-97478-1.

- ↑ Harris, Constance (1976). "Biosynthesis of Griseofulvin". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 98 (17): 5380–5386. doi:10.1021/ja00433a053.

External links

| External sites: |

|

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |