Aspergilloma

| Aspergilloma | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Mycetoma, fungus ball, moldy lungs | |

| |

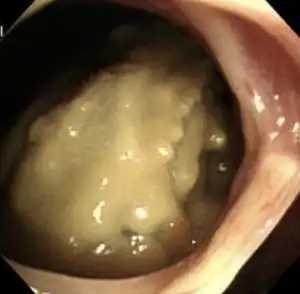

| Aspergilloma at fibreoptic bronchoscopy | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Causes | Aspergillus[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Chest x-ray, serology, sputum culture |

Aspergilloma is a type of fungal infection that appears as a clump of Aspergillus, mucus and debris, typically in the lungs.[1]

It was first described by Deve in 1938.[1]

Signs and symptoms

People with aspergillomata typically remain asymptomatic until the condition is fairly advanced; in some cases even for decades. Diagnosis is often made as a result of an incidental finding on a chest X-ray or CT scan that may be performed as part of the workup for another unrelated condition. However, a small percentage of aspergillomata invade into a blood vessel which can result in bleeding. Thus, the most common symptom of associated with aspergillomata is coughing up blood (hemoptysis). This may result in life-threatening hemorrhage, though the amount of blood lost is usually inconsequential.

Aspergillomata can also form in other organs. They can form abscesses in solid organs such as the brain or kidney, usually in people who are immunocompromised. They can also develop within body cavities such as the sphenoid or paranasal sinuses,[2] the ear canal, and rarely on surfaces such as heart valves.

Cause

The most common organ affected by aspergilloma is the lung. Aspergilloma mainly affects people with underlying cavitary lung disease such as tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis and systemic immunodeficiency. Aspergillus fumigatus, the most common causative species, is typically inhaled as small (2 to 3 micron) spores. The fungus settles in a cavity and is able to grow free from interference because critical elements of the immune system are unable to penetrate into the cavity. As the fungus multiplies, it forms a ball, which incorporates dead tissue from the surrounding lung, mucus, and other debris.[3]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of aspergilloma is by serum IgE levels which are usually raised in this condition.

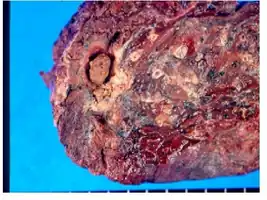

Gross view of fungus ball after left upper lobectomy

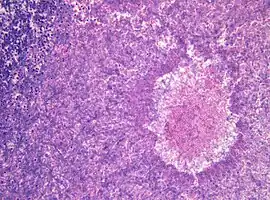

Gross view of fungus ball after left upper lobectomy Histopathology of aspergilloma, H&E staining

Histopathology of aspergilloma, H&E staining Aspergillomas complicating tuberculosis: multiple aspergillomas within large cavitary lesions of tuberculous origin.

Aspergillomas complicating tuberculosis: multiple aspergillomas within large cavitary lesions of tuberculous origin.

Treatment

Most cases of aspergilloma do not require treatment. Treatment of diseases which increase the risk of aspergilloma, such as tuberculosis, may help to prevent their formation. In cases complicated by severe hemoptysis or other associated conditions such as pleural empyema or pneumothorax, surgery may be required to remove the aspergilloma and the surrounding lung tissue by doing a lobectomy or other types of resection and thus stop the bleeding. There has been interest in treatment with antifungal medications such as itraconazole, none has yet been shown to reliably eradicate aspergillomata.

Although most fungi—and especially Aspergillus—fail to grow in healthy human tissue, significant growth may occur in people whose adaptive immune system is compromised, such as those with chronic granulomatous disease, who are undergoing chemotherapy, or who have recently undergone a bone marrow transplantation. Within the lungs of such individuals, the fungal hyphae spread out as a spherical growth. With the restoration of normal defense mechanisms, neutrophils and lymphocytes are attracted to the edge of the spherical fungal growth where they lyse, releasing tissue-digesting enzymes as a normal function. A sphere of the infected lung is thus cleaved from the adjacent lung. This sphere flops around in the resulting cavity and is recognized on x-ray as a fungus ball. This process is beneficial as a potentially serious invasive fungal infection is converted into surface colonization. Although the fungus is inactivated in the process, surgeons may choose to operate to reduce the possibility of bleeding. Microscopic examination of surgically removed recently formed fungus balls clearly shows a sphere of dead lung containing fungal hyphae. Microscopic examination of older lesions reveals mummified tissue which may reveal faint residual lung or hyphal structures.[4]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Chakraborty, Rebanta K.; Baradhi, Krishna M. (2023). "Aspergilloma". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 2022-08-17. Retrieved 2023-06-23.

- ↑ "Life". Archived from the original on 2017-06-22. Retrieved 2021-06-26.

- ↑ Soubani AO, Chandrasekar PH (June 2002). "The clinical spectrum of pulmonary aspergillosis". Chest. 121 (6): 1988–9. doi:10.1378/chest.121.6.1988. PMID 12065367. Archived from the original on 2013-04-14.

- ↑ Przyjemski, CJ; Mattii, R (1980). "The Formation of Pulmonary Mycetomata". Cancer. 46 (7): 1701–1704. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19801001)46:7<1701::AID-CNCR2820460733>3.0.CO;2-4. PMID 6932257.

Further reading

- F, Deve (1938). "Une nouvelle forme anatomo-radiologique de mycose pulmonaire primitive, Le mega-mycetome intrabronchectasique". Arch Med-Chir Appl Respir. 13: 337–361. Archived from the original on 2023-08-02. Retrieved 2023-07-30.

External links

| Classification |

|---|