Zygomycosis

| Mucormycosis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Periorbital fungal infection known as mucormycosis, or phycomycosis | |

Zygomycosis is the broadest term to refer to infections caused by bread mold fungi of the zygomycota phylum. However, because zygomycota has been identified as polyphyletic, and is not included in modern fungal classification systems, the diseases that zygomycosis can refer to are better called by their specific names: mucormycosis[1] (after Mucorales), phycomycosis[2] (after Phycomycetes) and basidiobolomycosis (after Basidiobolus).[3] These rare yet serious and potentially life-threatening fungal infections usually affect the face or oropharyngeal (nose and mouth) cavity.[4] Zygomycosis type infections are most often caused by common fungi found in soil and decaying vegetation. While most individuals are exposed to the fungi on a regular basis, those with immune disorders (immunocompromised) are more prone to fungal infection.[2][5][6] These types of infections are also common after natural disasters, such as tornadoes or earthquakes, where people have open wounds that have become filled with soil or vegetative matter.[7]

The condition may affect the gastrointestinal tract or the skin, often beginning in the nose and paranasal sinuses. It is one of the most rapidly spreading fungal infections in humans. Treatment consists of prompt and intensive antifungal drug therapy and surgery to remove the infected tissue.

Symptoms and signs

In the primary cutaneous form, the lesions are usually painful and necrotic, with black eschar, accompanied by a fever. Patients will usually present with a history of poorly controlled diabetes or malignancy.[8] Myocutaneous infectious may lead to amputation. Pulmonary tract infections seen with lung transplant patients, who are at high risk for fatal invasive mycoses.[9] Rhinocerebral infection is characterized by paranasal swelling with necrotic tissues. Patient may have hemorrhagic exudates (tissue fluid from lesions tinged with blood) from the nose and eyes as the fungi penetrate through blood vessels and other anatomical structures.[10]

.jpg.webp) Zygomycosis

Zygomycosis.jpg.webp) Zygomycosis

Zygomycosis

Causes

Pathogenic zygomycosis is caused by species in two orders: Mucorales or Entomophthorales, with the former causing far more disease than the latter.[11] These diseases are known as "mucormycosis" and "entomophthoramycosis", respectively.[12]

- Order Mucorales (mucormycosis)

- Family Mucoraceae

- Absidia (Absidia corymbifera)

- Apophysomyces (Apophysomyces elegans and Apophysomyces trapeziformis)

- Mucor (Mucor indicus)

- Rhizomucor (Rhizomucor pusillus)

- Rhizopus (Rhizopus oryzae)

- Family Cunninghamellaceae

- Cunninghamella (Cunninghamella bertholletiae)

- Family Thamnidiaceae

- Cokeromyces (Cokeromyces recurvatus)

- Family Saksenaeaceae

- Saksenaea (Saksenaea vasiformis)

- Family Syncephalastraceae

- Syncephalastrum (Syncephalastrum racemosum)

- Family Mucoraceae

- Order Entomophthorales (entomophthoramycosis)

- Family Basidiobolaceae

- Basidiobolus (Basidiobolus ranarum)

- Family Ancylistaceae

- Conidiobolus (Conidiobolus coronatus/Conidiobolus incongruus)

- Family Basidiobolaceae

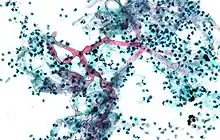

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is done with potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation in tissue. On light microscopy, there will be broad, ribbon-like septate hyphae with 90 degree angles on branches.[10] KOH wet mount of the black eschar will show aseptate fungal hyphae with right angle branching. Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS) staining will reveal similar broad hyphae in the dermis and cutis. Fungal culture can also confirm the organism.[13] Diagnosis remains difficult due to the lack of laboratory tests as mortality remains high. In 2005, a multiplex PCR test was able to identify five species of Rhizopus and may prove useful as a screening method for visceral mucormycosis in the future.[14]

The clinical approach to diagnosis includes radiologic, where more than ten nodules and pleural effusion are associated to pulmonary forms of the disease. In CT, a reverse halo sign is noted. Direct microscopy and histopathology, and cultures remain the gold standards for diagnoses.[15] Zygomycophyta share close clinical and radiological features to Aspergillosis. Invasive procedures such as bronchial endoscopy and lung biopsy may be necessary to confirm pulmonary diagnosis are no validated indirect tests are available. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction to detect serum DNA of the pathogen shows promise.[16]

Treatment

The condition may affect the gastrointestinal tract or the skin In non-trauma cases, it usually begins in the nose and paranasal sinuses and is one of the most rapidly spreading fungal infections in humans.[2] Common symptoms include thrombosis and tissue necrosis.[17]

Due to the organisms' rapid growth and invasion, zygomycosis presents with a high fatality rate. Treatment must begin immediately with debridement of the necrotic tissue plus Amphotericin B.[10] Complete excision of the infectious tissue may be required as suspected dead tissue must be excised aggressively.[13][18][19] Documented case of conservative surgical drainage, intravenous amphotericin B in and insulin-dependent diabetic have proven effective in sino-orbital infection.[20] The prognosis varies vastly depending upon an individual patient's circumstances.[17]

Epidemiology

Zygomycosis has been found in survivors of the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami and in survivors of the 2011 Joplin, Missouri tornado.[21]

Other animals

The term oomycosis is used to describe oomycete infections.[22] These are more common in animals, notably dogs and horses. These are heterokonts, not true fungi. Types include pythiosis (caused by Pythium insidiosum) and lagenidiosis.

Zygomycosis has been described in a cat, where fungal infection of the tracheobronchus led to respiratory disease requiring euthanasia.[23]

References

- ↑ Toro, Carlos; del Palacio, Amalia; Álvarez, Carmen; Rodríguez-Peralto, José Luis; Carabias, Esperanza; Cuétara, Soledad; Carpintero, Yolanda; Gómez, César (1998). "Zigomicosis cutánea por Rhizopus arrhizus en herida quirúrgica" [Cutaneous zygomycosis caused by Rhizopus arrhizus in a surgical wound]. Revista Iberoamericana de Micología (in español). 15 (2): 94–6. PMID 17655419. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- 1 2 3 Auluck, Ajit (2007). "Maxillary necrosis by mucormycosis. a case report and literature review" (PDF). Medicina Oral Patologia Oral y Cirugia Bucal. 12 (5): E360–4. PMID 17767099. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1999). "Gastrointestinal Basidiobolomycosis — Arizona, 1994–1999". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 48 (32): 710–3. PMID 21033182. Archived from the original on 14 July 2018. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ↑ Nancy F Crum-Cianflone; MD MPH. "Mucormycosis". eMedicine. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 19 May 2008.

- ↑ "MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia: Mucormycosis". Archived from the original on 20 May 2008. Retrieved 19 May 2008.

- ↑ Ettinger, Stephen J.; Feldman, Edward C. (1995). Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine (4th ed.). W.B. Saunders Company. ISBN 0-7216-6795-3.

- ↑ Draper, Bill; Suhr, Jim (11 June 2011). "Survivors of Joplin tornado develop rare infection". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Associated Press.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ Rodríguez-Lobato E, Ramírez-Hobak L, Aquino-Matus JE, Ramírez-Hinojosa JP, Lozano-Fernández VH, Xicohtencatl-Cortes J, Hernández-Castro R, Arenas R. Primary Cutaneous Mucormycosis Caused by Rhizopus oryzae: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Mycopathologia. 2017 Apr;182(3-4):387-392. doi: 10.1007/s11046-016-0084-6. Epub 2016 Nov 3. PMID 27807669.

- ↑ Mattner F, Weissbrodt H, Strueber M. Two case reports: fatal Absidia corymbifera pulmonary tract infection in the first postoperative phase of a lung transplant patient receiving voriconazole prophylaxis, and transient bronchial Absidia corymbifera colonization in a lung transplant patient. Scand J Infect Dis. 2004;36(4):312-4. doi: 10.1080/00365540410019408. PMID 15198193.

- 1 2 3 Moscatello, Kim (2013). USMLE Step 1: Immunology and Microbiology Lecture Notes. Chicago: Kaplan Publishing. pp. 430–431. ISBN 978-1625232557.

- ↑ Ribes, J. A.; Vanover-Sams, C. L.; Baker, D. J. (2000). "Zygomycetes in Human Disease". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 13 (2): 236–301. doi:10.1128/CMR.13.2.236. PMC 100153. PMID 10756000.

- ↑ Prabhu, R. M.; Patel, R. (2004). "Mucormycosis and entomophthoramycosis: A review of the clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 10: 31–47. doi:10.1111/j.1470-9465.2004.00843.x. PMID 14748801.

- 1 2 Li H, Hwang SK, Zhou C, Du J, Zhang J. Gangrenous cutaneous mucormycosis caused by Rhizopus oryzae: a case report and review of primary cutaneous mucormycosis in China over Past 20 years. Mycopathologia. 2013 Aug;176(1-2):123-8. doi: 10.1007/s11046-013-9654-z. Epub 2013 Apr 25. PMID 23615822.

- ↑ Nagao K, Ota T, Tanikawa A, Takae Y, Mori T, Udagawa S, Nishikawa T. Genetic identification and detection of human pathogenic Rhizopus species, a major mucormycosis agent, by multiplex PCR based on internal transcribed spacer region of rRNA gene. J Dermatol Sci. 2005 Jul;39(1):23-31. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2005.01.010. Epub 2005 Feb 25. PMID 15978416.

- ↑ Skiada A, Lass-Floerl C, Klimko N, Ibrahim A, Roilides E, Petrikkos G. Challenges in the diagnosis and treatment of mucormycosis. Med Mycol. 2018 Apr 1;56(suppl_1):93-101. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myx101. PMID 29538730; PMCID: PMC6251532.

- ↑ Danion F, Aguilar C, Catherinot E, Alanio A, DeWolf S, Lortholary O, Lanternier F. Mucormycosis: New Developments into a Persistently Devastating Infection. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2015 Oct;36(5):692-705. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1562896. Epub 2015 Sep 23. PMID 26398536.

- 1 2 Spellberg, B.; Edwards, J.; Ibrahim, A. (2005). "Novel Perspectives on Mucormycosis: Pathophysiology, Presentation, and Management". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 18 (3): 556–69. doi:10.1128/CMR.18.3.556-569.2005. PMC 1195964. PMID 16020690.

- ↑ Spellberg, Brad; Walsh, Thomas J.; Kontoyiannis, Dimitrios P.; Edwards, Jr.; Ibrahim, Ashraf S. (2009). "Recent Advances in the Management of Mucormycosis: From Bench to Bedside". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 48 (12): 1743–51. doi:10.1086/599105. PMC 2809216. PMID 19435437.

- ↑ Grooters, A (2003). "Pythiosis, lagenidiosis, and zygomycosis in small animals". Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice. 33 (4): 695–720. doi:10.1016/S0195-5616(03)00034-2. PMID 12910739.

- ↑ Rosenberger RS, West BC, King JW. Survival from sino-orbital mucormycosis due to Rhizopus rhizopodiformis. Am J Med Sci. 1983 Nov-Dec;286(3):25-30. doi: 10.1097/00000441-198311000-00004. PMID 6356916.

- ↑ "Joplin toll rises to 151; some suffer from fungus". Associated Press. 10 June 2011. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 17 February 2021 – via Medical Xpress.

- ↑ "Merck Veterinary Manual". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- ↑ Snyder, Katherine D.; Spaulding, Kathy; Edwards, John (2010). "Imaging diagnosis—tracheobronchial zygomycosis in a cat". Veterinary Radiology & Ultrasound. 51 (6): 617–20. doi:10.1111/j.1740-8261.2010.01720.x. PMID 21158233.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |