Thoracotomy

| Thoracotomy | |

|---|---|

| |

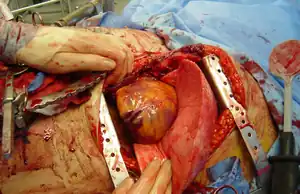

| A thoracotomy incision performed through the fourth or fifth intercostal space with rib spreaders to increase visibility of the pleural cavity | |

| Specialty | Cardiothoracic surgery |

A thoracotomy is a surgical procedure to gain access into the chest.[1] It involves making a cut between the ribs.[1]

It is performed by surgeons (emergency physicians or paramedics under certain circumstances) to gain access to the thoracic organs, most commonly the heart, the lungs, or the esophagus, or for access to the thoracic aorta or the anterior spine (the latter may be necessary to access tumors in the spine).

The purpose of a thoracotomy is the first step used to facilitate thoracic surgeries including lobectomy or pneumonectomy for lung cancer or to gain thoracic access in major trauma.

There are several different surgical approaches.[1]

Approaches

There are many different surgical approaches to performing a thoracotomy. Some common forms of thoracotomies include:

- Median sternotomy provides wide access to the mediastinum and is the incision of choice for most open-heart surgery and access to the anterior mediastinum

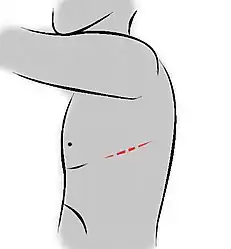

- Posterolateral thoracotomy is an incision through an intercostal space on the back, and is often widened with rib spreaders. It is a very common approach for operations on the lung or posterior mediastinum, including the esophagus. When performed over the fifth intercostal space, it allows optimal access to the pulmonary hilum (pulmonary artery and pulmonary vein) and therefore is considered the approach of choice for pulmonary resection (pneumonectomy and lobectomy).

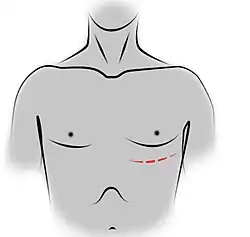

- Anterolateral thoracotomy is performed upon the anterior chest wall; left anterolateral thoracotomy is the incision of choice for open chest massage, a critical maneuver in the management of traumatic cardiac arrest. Anterolateral thoracotomy, like most surgical incisions, requires the use of tissue retractors—in this case, a "rib spreader" such as the Tuffier retractor.

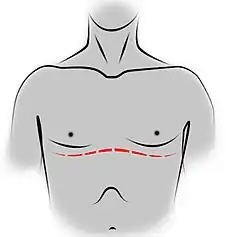

- Bilateral anterolateral thoracotomy combined with transverse sternotomy results in the "clamshell" incision

- The Ashrafian or Aztec thoracotomy was devised to give rapid access to the heart and pericardium through an incision that consists of an anterior thoracic incision followed in a vertical direction along the costo-chondral (rib-cartilage) junction.[2]

Upon completion of the surgical procedure, the chest is closed. One or more chest tubes—with one end inside the opened pleural cavity and the other submerged under saline solution inside a sealed container, forming an airtight drainage system—are necessary to remove air and fluid from the pleural cavity, preventing the development of pneumothorax or hemothorax.

Complications

In addition to pneumothorax, complications from thoracotomy include air leaks, infection, bleeding and respiratory failure. Postoperative pain is universal and intense, generally requiring the use of opioid analgesics for moderation, as well as interfering with the recovery of respiratory function. Paraplegia complicating thoracotomy is rare but catastrophic.[3][4]

In nearly all cases a chest tube, or more than one chest tube is placed. These tubes are used to drain air and fluid until the patient heals enough to take them out (usually a few days). Complications such as pneumothorax, tension pneumothorax, or subcutaneous emphysema can occur if these chest tubes become clogged. Furthermore, complications such as pleural effusion or hemothorax can occur if the chest tubes fail to drain the fluid around the lung in the pleural space after a thoracotomy. Clinicians should be on the look out for chest tube clogging as these tubes have a tendency to become occluded with fibrinous material or clot in the post operative period, and when this happens, complications ensue.

Pain following a thoracotomy may be treated by the use of a nerve block known as a rhomboid intercostal block.[5] In the long term, post-operative chronic pain can develop, known as thoracotomy pain syndrome, and may last from a few years to a lifetime. Treatment to aid pain relief for this condition includes intra-thoracic nerve blocks/opiates and epidurals, although results vary from person to person and are dependent on numerous factors. A recent Cochrane review concluded that there is moderate-quality evidence that regional anaesthesia may reduce the risk of developing persistent postoperative pain after three to 18 months after thoracotomy.[6]

VATS

Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) is a less invasive alternative to thoracotomy in selected cases, much like laparoscopic surgery.

Complications

Thoracic epidural analgesia or paravertebral blockade have shown to be the most effective methods for post-thoracotomy pain control. However, contraindications to neuraxial anesthesia include hypovolemia, shock, increase in ICP, coagulopathy or thrombocytopenia, sepsis, or infection at puncture site. Comparing thoracic epidural analgesia and paravertebral blockade, paravertebral blockade reduced the risks of developing minor complications, hovewer paravertebral blockade was as effective as thoracic epidural blockade in controlling acute pain.[7] Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation has also shown to be useful in the management of post-thoracotomy pain. Specifically, it has been found to be a good adjunct in the management of moderate to severe post-thoracotomy pain and effective as a lone modality in mild post-thoracotomy pain (e.g. after video-assisted thoracoscopy).[8]

See also

- List of surgeries by type

References

- 1 2 3 Chang, Brian; Tucker, William D.; Burns, Bracken (2022). "Thoracotomy". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 32491532. Archived from the original on 2022-02-16. Retrieved 2022-02-16.

- ↑ Ashrafian H, Athanasiou T (December 2010). "Emergency prehospital on-scene thoracotomy: a novel method". Collegium Antropologicum. 34 (4): 1449–52. PMID 21874737.

- ↑ Attar S, Hankins JR, Turney SZ, Krasna MJ, McLaughlin JS (June 1995). "Paraplegia after thoracotomy: report of five cases and review of the literature". The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 59 (6): 1410–5, discussion 1415-6. doi:10.1016/0003-4975(95)00196-R. PMID 7771819.

- ↑ Brodbelt AR, Miles JB, Foy PM, Broome JC (March 2002). "Intraspinal oxidised cellulose (Surgicel) causing delayed paraplegia after thoracotomy--a report of three cases". Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 84 (2): 97–9. PMC 2503802. PMID 11995773.

- ↑ Ökmen K (April 2019). "Efficacy of rhomboid intercostal block for analgesia after thoracotomy". Korean J Pain. 32 (2): 129–132. doi:10.3344/kjp.2019.32.2.129. PMC 6549589. PMID 31091512.

- ↑ Weinstein EJ, Levene JL, Cohen MS, Andreae DA, Chao JY, Johnson M, et al. (June 2018). "Local anaesthetics and regional anaesthesia versus conventional analgesia for preventing persistent postoperative pain in adults and children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6 (2): CD007105. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007105.pub4. PMC 6377212. PMID 29926477.

- ↑ Yeung JH, Gates S, Naidu BV, Wilson MJ, Gao Smith F, et al. (Cochrane Anaesthesia Group) (February 2016). "Paravertebral block versus thoracic epidural for patients undergoing thoracotomy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2: CD009121. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009121.pub2. PMC 7151756. PMID 26897642.

- ↑ Ferreira, FC, et al. Assessing the effects of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) in post-thoracotomy analgesia. Rev Bras Anestesiol. 2011 Sep-Oct;61(5):561-7, 308-10. doi:10.1016/S0034-7094(11)70067-8.