Mitochondrial neurogastrointestinal encephalopathy syndrome

| Mitochondrial neurogastrointestinal encephalopathy syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names: MNGIE syndrome | |

| |

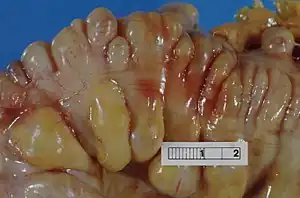

| Diverticula, one of the gastrointestinal symptoms of MNGIE | |

Mitochondrial neurogastrointestinal encephalopathy syndrome (MNGIE) is a rare autosomal recessive mitochondrial disease.[1] It has been previously referred to as polyneuropathy, ophthalmoplegia, leukoencephalopathy, and POLIP syndrome.[2] The disease presents in childhood, but often goes unnoticed for decades.[1][3][4] Unlike typical mitochondrial diseases caused by mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations, MNGIE is caused by mutations in the TYMP gene, which encodes the enzyme thymidine phosphorylase.[1][4] Mutations in this gene result in impaired mitochondrial function, leading to intestinal symptoms as well as neuro-ophthalmologic abnormalities.[1][3] A secondary form of MNGIE, called MNGIE without leukoencephalopathy, can be caused by mutations in the POLG gene.[2]

Signs and symptoms

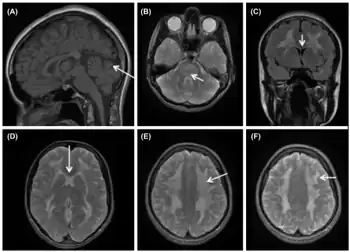

Like other mitochrondrial diseases, MNGIE is a multisystem disorder.[5] MNGIE primarily affects the gastrointestinal and neurological systems. Gastrointestinal symptoms may include gastrointestinal dysmotility, due to inefficient peristalsis, which may result in pseudo-obstruction and cause malabsorption of nutrients.[1][4] Additionally, gastrointestinal symptoms such as borborygmi, early satiety, diarrhea, constipation, gastroparesis, nausea, vomiting, weight loss, and diverticulitis may be present in MNGIE patients.[1] Neurological symptoms may include diffuse leukoencephalopathy, peripheral neuropathy, and myopathy.[1] Ocular symptoms may include retinal degeneration, ophthalmoplegia, and ptosis.[1][4] Those with MNGIE are often thin and experience continuous weight loss. The characteristic thinness of MNGIE patients is caused by multiple factors including inadequate caloric intake due to gastrointestinal symptoms and discomfort, malabsorption of food from bacterial overgrowth due to decreased motility, as well as an increased metabolic demand due to inefficient production of ATP by the mitochondria.

Genetics

A variety of mutations in the TYMP gene have been discovered that lead to the onset of mitochondrial neurogastrointestinal encephalopathy syndrome.[1] The TYMP gene is a nuclear gene, however, mutations in the TYMP gene affect mitochrondrial DNA and function.[1] Mutations in this gene result in a loss of thymidine phosphorylase activity.[1] Thymidine phosphorylase is the enzymatic product of the TYMP gene and is responsible for breaking down thymidine nucleosides into thymine and 2-deoxyribose 1-phosphate.[1] Without normal thymidine phosphorylase activity, thymidine nucleosides begin to build up in cells.[1] High nucleoside levels are toxic to mitochondrial DNA and cause mutations that lead to dysfunction of the respiratory chain, and thus, inadequate energy production in the cells.[1] These mitochondrial effects are responsible for the symptomatology associated with the disease.[1]

Diagnosis

While the disease manifests early in life in most cases, diagnosis of the disease is often quite delayed.[1][3][4] The symptoms that affected patients present vary, but the most common presenting symptoms are gastrointestinal issues such as nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhea, and neurologic or ocular symptoms such as hearing loss, weakness, and peripheral neuropathy.[3] These gastrointestinal symptoms cause patients with MNGIE to be very thin and experience persistent weight loss and this often leads to MNGIE being misdiagnosed as an eating disorder.[1] These symptoms without presentation of disordered eating and warped body image warrant further investigation into the possibility of MNGIE as a diagnosis.[1] Presentation of these symptoms and lack of disordered eating are not enough for a diagnosis. Radiologic studies showing hypoperistalsis, large atonic stomach, dilated duodenum, diverticula, and white matter changes are required to confirm the diagnosis.[3] Elevated blood and urine nucleoside levels are also indicative of MNGIE syndrome.[1] Abnormal nerve conduction as well as analysis of mitochondria from liver, intestines, muscle, and nerve tissue can also be used to support the diagnosis.[1][3]

Management

A successful treatment for MNGIE has yet to be found, however, symptomatic relief can be achieved using pharmacotherapy and celiac plexus neurolysis.[3] Celiac plexus neurolysis involves interrupting neural transmission from various parts of the gastrointestinal tract. By blocking neural transmission, pain is relieved and gastrointestinal motility increases.[3] Stem cell therapies are currently being investigated as a potential cure for certain patients with the disease, however, their success depends on physicians catching the disease early before too much organ damage has occurred.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Garone, Caterina; Tadesse, Saba; Hirano, Michio (2011-11-01). "Clinical and genetic spectrum of mitochondrial neurogastrointestinal encephalomyopathy". Brain. 134 (11): 3326–3332. doi:10.1093/brain/awr245. ISSN 0006-8950. PMC 3212717. PMID 21933806.

- 1 2 "OMIM Entry - # 603041 - MITOCHONDRIAL DNA DEPLETION SYNDROME 1 (MNGIE TYPE); MTDPS1". omim.org. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2015-12-02.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Teitelbaum, J.E. (September 2002). "Diagnosis and Management of MNGIE in Children: Case Report and Review of the Literature". Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 35 (3): 377–83. doi:10.1097/00005176-200209000-00029. PMID 12352533.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Walia, Anuj (December 2006). "Mitochondrial neuro-gastrointestinal encephalopathy syndrome" (PDF). Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 73 (12): 1112–1114. doi:10.1007/BF02763058. PMID 17202642. S2CID 40345738. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-06-16. Retrieved 2022-07-30.

- ↑ Bardosi, A (1987). "Myo-, Neuro-, Gastrointestinal Encephalopathy (MNGIE Syndrome) due to partial deficiency of cytochrome-C oxidase: A new mitochondrial multisystem disorder". Acta Neuropathologica. 74 (3): 248–58. doi:10.1007/BF00688189. PMID 2823522. S2CID 20379299.

- ↑ "EMBL European Bioinformatics Institute". www.ebi.ac.uk. Retrieved 2015-12-03.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|