Parasitology

Parasitology is the study of parasites, their hosts, and the relationship between them. As a biological discipline, the scope of parasitology is not determined by the organism or environment in question but by their way of life. This means it forms a synthesis of other disciplines, and draws on techniques from fields such as cell biology, bioinformatics, biochemistry, molecular biology, immunology, genetics, evolution and ecology.

Fields

The study of these diverse organisms means that the subject is often broken up into simpler, more focused units, which use common techniques, even if they are not studying the same organisms or diseases. Much research in parasitology falls somewhere between two or more of these definitions. In general, the study of prokaryotes falls under the field of bacteriology rather than parasitology.

Medical

The parasitologist F.E.G. Cox noted that "Humans are hosts to nearly 300 species of parasitic worms and over 70 species of protozoa, some derived from our primate ancestors and some acquired from the animals we have domesticated or come in contact with during our relatively short history on Earth".[2]

One of the largest fields in parasitology, medical parasitology is the subject that deals with the parasites that infect humans, the diseases caused by them, clinical picture and the response generated by humans against them. It is also concerned with the various methods of their diagnosis, treatment and finally their prevention & control. A parasite is an organism that live on or within another organism called the host. These include organisms such as:

- Plasmodium spp., the protozoan parasite which causes malaria. The four species infective to humans are P. falciparum, P. malariae, P. vivax and P. ovale.

- Leishmania, unicellular organisms which cause leishmaniasis

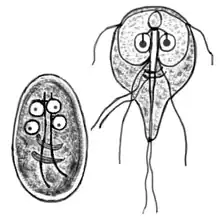

- Entamoeba and Giardia, which cause intestinal infections (dysentery and diarrhoea)

- Multicellular organisms and intestinal worms (helminths) such as Schistosoma spp., Wuchereria bancrofti, Necator americanus (hookworm) and Taenia spp. (tapeworm)

- Ectoparasites such as ticks, scabies and lice

Medical parasitology can involve drug development, epidemiological studies and study of zoonoses.

Veterinary

The study of parasites that cause economic losses in agriculture or aquaculture operations, or which infect companion animals. Examples of species studied are:

- Lucilia sericata, a blowfly, which lays eggs on the skins of farm animals. The maggots hatch and burrow into the flesh, distressing the animal and causing economic loss to the farmer

- Otodectes cynotis, the cat ear mite, responsible for Canker.

- Gyrodactylus salaris, a monogenean parasite of salmon, which can wipe out populations which are not resistant.

Structural

This is the study of structures of proteins from parasites. Determination of parasitic protein structures may help to better understand how these proteins function differently from homologous proteins in humans. In addition, protein structures may inform the process of drug discovery.

Quantitative

Parasites exhibit an aggregated distribution among host individuals, thus the majority of parasites live in the minority of hosts. This feature forces parasitologists to use advanced biostatistical methodologies.[3]

Parasite ecology

Parasites can provide information about host population ecology. In fisheries biology, for example, parasite communities can be used to distinguish distinct populations of the same fish species co-inhabiting a region. Additionally, parasites possess a variety of specialized traits and life-history strategies that enable them to colonize hosts. Understanding these aspects of parasite ecology, of interest in their own right, can illuminate parasite-avoidance strategies employed by hosts.

Conservation biology of parasites

Conservation biology is concerned with the protection and preservation of vulnerable species, including parasites. A large proportion of parasite species are threatened by extinction, partly due to efforts to eradicate parasites which infect humans or domestic animals, or damage human economy, but also caused by the decline or fragmentation of host populations and the extinction of host species.

Taxonomy and phylogenetics

The huge diversity between parasitic organisms creates a challenge for biologists who wish to describe and catalogue them. Recent developments in using DNA to identify separate species and to investigate the relationship between groups at various taxonomic scales has been enormously useful to parasitologists, as many parasites are highly degenerate, disguising relationships between species.

History

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek observed and illustrated Giardia lamblia in 1681, and linked it to "his own loose stools". This was the first protozoan parasite of humans that he recorded, and the first to be seen under a microscope.[4]

A few years later, in 1687, the Italian biologists Giovanni Cosimo Bonomo and Diacinto Cestoni published that scabies is caused by the parasitic mite Sarcoptes scabiei, marking scabies as the first disease of humans with a known microscopic causative agent.[5] In the same publication, Esperienze Intorno alla Generazione degl'Insetti (Experiences of the Generation of Insects), Francesco Redi also described ecto- and endoparasites, illustrating ticks, the larvae of nasal flies of deer, and sheep liver fluke. His earlier (1684) book Osservazioni intorno agli animali viventi che si trovano negli animali viventi (Observations on Living Animals found in Living Animals) described and illustrated over 100 parasites including the human roundworm.[6] He noted that parasites develop from eggs, contradicting the theory of spontaneous generation.[7]

Modern parasitology developed in the 19th century with accurate observations by several researchers and clinicians. In 1828, James Annersley described amoebiasis, protozoal infections of the intestines and the liver, though the pathogen, Entamoeba histolytica, was not discovered until 1873 by Friedrich Lösch. James Paget discovered the intestinal nematode Trichinella spiralis in humans in 1835. James McConnell described the human liver fluke in 1875. A physician at the French naval hospital at Toulon, Louis Alexis Normand, in 1876 researching the ailments of French soldiers returning from what is now Vietnam, discovered the only known helminth that, without treatment, is capable of indefinitely reproducing within a host and causes the disease strongyloidiasis.[8] Patrick Manson discovered the life cycle of elephantiasis, caused by nematode worms transmitted by mosquitoes, in 1877. Manson further predicted that the malaria parasite, Plasmodium, had a mosquito vector, and persuaded Ronald Ross to investigate. Ross confirmed that the prediction was correct in 1897–1898. At the same time, Giovanni Battista Grassi and others described the malaria parasite's life cycle stages in Anopheles mosquitoes. Ross was controversially awarded the 1902 Nobel prize for his work, while Grassi was not.[4]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Parasitology. |

- European Federation of Parasitologists

- Category:Parasitologists

References

- ↑ Roncalli Amici R (2001). "The history of Italian parasitology" (PDF). Veterinary Parasitology. 98 (1–3): 3–10. doi:10.1016/S0304-4017(01)00420-4. PMID 11516576. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-23.

- ↑ Cox F.E.G. 2002. "History of human parasitology"

- ↑ Rózsa, L.; Reiczigel, J.; Majoros, G. (2000). "Quantifying parasites in samples of hosts". J. Parasitol. 86 (2): 228–32. doi:10.1645/0022-3395(2000)086[0228:QPISOH]2.0.CO;2. PMID 10780537.

- 1 2 Cox, Francis E. G. (June 2004). "History of human parasitic diseases". Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 18 (2): 173–174. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2004.01.001. PMID 15145374.

- ↑ "The cause of scabies"

- ↑ Ioli, A; Petithory, J.C.; Theodorides, J. (1997). "Francesco Redi and the birth of experimental parasitology". Hist Sci Med. 31 (1): 61–66. PMID 11625103.

- ↑ Bush, A. O.; Fernández, J. C.; Esch, G. W.; Seed, J. R. (2001). Parasitism: The Diversity and Ecology of Animal Parasites. Cambridge University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0521664479.

- ↑ Cox, F. E (2002). "History of Human Parasitology". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 15 (4): 595–612. doi:10.1128/CMR.15.4.595-612.2002. PMC 126866. PMID 12364371.

Bibliography

- Loker, E., & Hofkin, B. (2015). Parasitology: a conceptual approach. Garland Science.