Pelvic pain

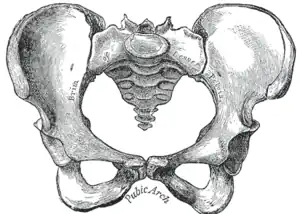

| Pelvic pain | |

|---|---|

| |

| Female type pelvis | |

| Specialty | Gynecology |

| Types | Acute, chronic[1] |

| Diagnostic method | History of symptoms, physical examination, laboratory testing, medical imaging[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Female: Menstrual cramps, endometriosis, ectopic pregnancy, pelvic inflammatory disease, ovarian torsion[3][4][2] Gastrointestinal: Appendicitis, irritable bowel syndrome, gastroenteritis, constipation[4][5][2] Urinary: Bladder infection, kidney stone, interstitial cystitis[4] Other: Fibromyalgia, abdominal wall muscle injury, abdominal aortic aneurysm[4] |

| Frequency | Common[5] |

Pelvic pain is pain between the region of the hips.[4] The pain can be acute, meaning it is is of sudden onset, or chronic, meaning it remains present either intermittently or continuously for a prolonged period of time.[1] If the pain lasts for less than 3 month it is generally classified as acute;[2] while if it last more than six months it is generally classified as chronic.[5] Depression may worsen symptoms.[4] It is separate from perineal pain.[3]

Causes of pelvic pain may relate to the female reproductive organs, the gastrointestinal or urinary tract, or structures near the pelvis such as the lower aspect of the aorta.[4] Common causes related to the female reproductive organs include menstrual cramps, endometriosis, and fibroids; while serious causes include ectopic pregnancy, pelvic inflammatory disease, and ovarian torsion.[3][4][2] Common causes related to the gastrointestinal tract include irritable bowel syndrome, gastroenteritis, constipation, and colon cancer.[4][5] Other serious causes include appendicitis.[2] Common causes related to the urinary tract include bladder infections, kidney stones, and interstitial cystitis.[4] Other causes include fibromyalgia, abdominal wall muscle injury, and abdominal aortic aneurysm.[4] Chronic pain may also occur following sexual abuse.[4]

Diagnostic work up includes the history of symptoms and physical examination and may be supported by laboratory testing and medical imaging.[2] A pregnancy test is recommended in all women who could potentially be pregnant.[2] Worrisome findings include fever, vaginal bleeding after menopause, low blood pressure, and peritonitis.[3]

Pelvic pain can affect both women and men though chronic pelvic pain most commonly affects women.[5] About 2% to 24% of women have pelvic pain unrelated to their menstural cycle, 8% to 21% have pain with sex, and 17% to 81% have pain with their periods.[5] Chronic pelvic pain occurs in at least 6 to 27% of women.[5]

Causes

Female

Many different conditions can cause pelvic pain including:

- Dysmenorrhea—pain during the menstrual period

- Endometriosis—pain caused by uterine tissue that is outside the uterus. Endometriosis can be visually confirmed by laparoscopy in approximately 75% of adolescent girls with chronic pelvic pain that is resistant to treatment, and in approximately 50% of adolescent in girls with chronic pelvic pain that is not necessarily resistant to treatment.[6]

- Pelvic inflammatory disease—pain caused by damage from infections

- Ovarian cysts—the ovary produces a large, painful cyst, which may rupture

- Ovarian torsion—the ovary is twisted in a way that interferes with its blood supply

- Ectopic pregnancy—a pregnancy implanted outside the uterus

- Polycystic ovary syndrome

- Adenomyosis

Both

- pelvic girdle pain (SPD or DSP)

- pudendal nerve entrapment

- Loin pain hematuria syndrome

- Proctitis—infection or inflammation of the anus or rectum

- Colitis—infection or inflammation of the colon

- Appendicitis—infection or inflammation of the bowel

Diagnosis

Females

The diagnostic workup begins with a history and examination, followed by a pregnancy test if pregnancy is possible. Bloodwork and medical imaging may be useful, and a handful may also benefit from having surgical evaluation.

The absence of visible pathology in chronic pain syndromes should not form the basis for either seeking psychological explanations or questioning the reality of the patient’s pain. Instead it is essential to approach the complexity of chronic pain from a psychophysiological perspective which recognises the importance of the mind-body interaction. Some of the mechanisms by which the limbic system impacts on pain, and in particular myofascial pain, have been clarified by research findings in neurology and psychophysiology.

Males

In chronic pelvic pain there are no standard diagnostic tests in males; diagnosis is by exclusion of other disease entities.

Chronic pelvic pain (category IIIB) is often misdiagnosed as chronic bacterial prostatitis and needlessly treated with antibiotics exposing the patient to inappropriate antibiotic use and unnecessarily to adverse effects with little if any benefit in most cases. Within a Bulgarian study, where by definition all patients had negative microbiological results, a 65% adverse drug reaction rate was found for patients treated with ciprofloxacin in comparison to a 9% rate for the placebo patients. This was combined with a higher cure rate (69% v 53%) found within the placebo group.[7]

Treatment

Females

Many women will benefit from a consultation with a physical therapist, a trial of anti-inflammatory medications, hormonal therapy, or even neurological agents.

A hysterectomy is sometimes performed.[8]

Spinal cord stimulation has been explored as a potential treatment option for some time, however there remains to be consensus on where the optimal location of the spinal cord this treatment should be aimed. As the innervation of the pelvic region is from the sacral nerve roots, previous treatments have been aimed at this region; results have been mixed. Spinal cord stimulation aimed at the mid- to high-thoracic region of the spinal cord have produced some positive results.[9]

Male

Multimodal therapy is the most successful treatment option in chronic pelvic pain,[10] and includes physical therapy,[11] myofascial trigger point release,[11] relaxation techniques,[11] α-blockers,[12] and phytotherapy.[13][14] The UPOINT diagnostic approach suggests that antibiotics are not recommended unless there is clear evidence of infection.[15][16]

Epidemiology

Female

Most women, at some time in their lives, experience pelvic pain. As girls enter puberty, pelvic or abdominal pain becomes a frequent complaint. Chronic pelvic pain is a common condition with rate of dysmenorrhoea between 16.8—81%, dyspareunia between 8—21.8%, and noncyclical pain between 2.1—24%.[17]

According to the CDC, Chronic pelvic pain (CPP) accounted for approximately 9% of all visits to gynecologists in 2007.[18] In addition, CPP is the reason for 20—30% of all laparoscopies in adults.[19] Pelvic girth pain is frequent during pregnancy.[20]

Society and culture

In the pursuit of better outcomes for people, problems have been found in current procedures for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain (CPP). These relate primarily with regard to the conceptual dichotomy between an ‘organic’ genesis of pain, where the presence of tissue damage is presumed, and a ‘psychogenic’ origin, where pain occurs despite a lack of damage to tissue.[21] CPP literature in medicine and psychiatry reflects a paradigm where unproblematically observable ‘organic’ processes are causally and sequentially explained, despite evidence in favour of a possible model which accounts for the “complex role played by meaning and consciousness” in the experience of pain.[21] While in the literature of causal mechanisms reference is made to ‘subjective’ aspects of pain, current models do not provide a means through which these aspects may be accessed or understood.[21] Without interpretive or ‘subjective’ approaches to the pain experienced by patients, medical understandings of CPP are fixed within ‘organic’ sequences of the “purely object” body conceptually separated from the patient.[21] Despite the prevalence of this wider understanding of the biological genesis of pain, alternate diagnosis and treatments of CPP in multidisciplinary settings have shown high success rates for people for whom ‘organic’ pathology has been unhelpful.[21]

Terminology

Urologic chronic pelvic pain syndrome (UCPPS) is an umbrella term adopted for use in research into pain syndromes associated with the male and female pelvis. It is not intended for use as a clinical diagnosis. The hallmark symptom for inclusion is chronic pain in the pelvis, pelvic floor or external genitalia, although this is often accompanied by lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS).[22]

Chronic pelvic pain in men is referred to as chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) and is also known as chronic nonbacterial prostatitis. Men in this category have no known infection, but do have extensive pelvic pain lasting more than 3 months.[23]

Research

In 2007, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), part of the United States National Institutes of Health, began using UCPPS as a term to refer to chronic pelvic pain syndromes, mainly interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) in women and chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) in men.[24]

References

- 1 2 "Pelvic Pain". www.hopkinsmedicine.org. Archived from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Bhavsar, AK; Gelner, EJ; Shorma, T (1 January 2016). "Common Questions About the Evaluation of Acute Pelvic Pain". American family physician. 93 (1): 41–8. PMID 26760839.

- 1 2 3 4 "Pelvic Pain - Gynecology and Obstetrics". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Archived from the original on 31 October 2020. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Pelvic Pain - Women's Health Issues". Merck Manuals Consumer Version. Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Chronic Pelvic Pain: ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 218". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 135 (3): e98–e109. March 2020. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000003716.

- ↑ Janssen, E. B.; Rijkers, A. C. M.; Hoppenbrouwers, K.; Meuleman, C.; d'Hooghe, T. M. (2013). "Prevalence of endometriosis diagnosed by laparoscopy in adolescents with dysmenorrhea or chronic pelvic pain: A systematic review". Human Reproduction Update. 19 (5): 570–582. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmt016. PMID 23727940.

- ↑ J. Dimitrakov; J. Tchitalov; T. Zlatanov; D. Dikov. "A Prospective, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study Of Antibiotics For The Treatment Of Category Iiib Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome In Men". Third International Chronic Prostatitis Network. Archived from the original on 19 June 2010. Retrieved 4 September 2009.

The results of our study show that antibiotics have an unacceptably high rate of adverse side effects as well as a statistically insignificant improvement over placebo...

- ↑ Kuppermann M, Learman LA, Schembri M, et al. (March 2010). "Predictors of hysterectomy use and satisfaction". Obstet Gynecol. 115 (3): 543–51. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181cf46a0. PMID 20177285.

- ↑ Hunter, C; Davé, N; Diwan, S; Deer, T (Jan 2013). "Neuromodulation of pelvic visceral pain: review of the literature and case series of potential novel targets for treatment". Pain Practice. 13 (1): 3–17. doi:10.1111/j.1533-2500.2012.00558.x. PMID 22521096.

- ↑ Potts JM (2005). "Therapeutic options for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome". Current Urology Reports. 6 (4): 313–7. doi:10.1007/s11934-005-0030-5. PMID 15978236.

- 1 2 3 Potts J, Payne RE (May 2007). "Prostatitis: Infection, neuromuscular disorder, or pain syndrome? Proper patient classification is key". Cleve Clin J Med. 74 Suppl 3: S63–71. doi:10.3949/ccjm.74.suppl_3.s63. PMID 17549825.

- ↑ Yang G, Wei Q, Li H, Yang Y, Zhang S, Dong Q (2006). "The effect of alpha-adrenergic antagonists in chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". J. Androl. 27 (6): 847–52. doi:10.2164/jandrol.106.000661. PMID 16870951.

...treatment duration should be long enough (more than 3 months)

- ↑ Shoskes DA, Zeitlin SI, Shahed A, Rajfer J (1999). "Quercetin in men with category III chronic prostatitis: a preliminary prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". Urology. 54 (6): 960–3. doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(99)00358-1. PMID 10604689.

- ↑ Elist J (2006). "Effects of pollen extract preparation Prostat/Poltit on lower urinary tract symptoms in patients with chronic nonbacterial prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study". Urology. 67 (1): 60–3. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2005.07.035. PMID 16413333.

- ↑ Sandhu J, Tu HY (2017). "Recent advances in managing chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome". F1000Res. 6: 1747. doi:10.12688/f1000research.10558.1. PMC 5615772. PMID 29034074.

- ↑ Zhu Y, Wang C, Pang X, Li F, Chen W, Tan W (May 2014). "Antibiotics are not beneficial in the management of category III prostatitis: a meta analysis". Urol J. 11 (2): 1377–85. PMID 24807747.

- ↑ Latthe P, Latthe M, Say L, Gülmezoglu M, Khan KS (2006). "WHO systematic review of prevalence of chronic pelvic pain: a neglected reproductive health morbidity". BMC Public Health. 6: 177. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-6-177. PMC 1550236. PMID 16824213.

- ↑ Hsiao, Chun-Ju (3 November 2010). "National Ambulatory medical Care Survey: 2007 Summary" (PDF). National Health Statistics Report. Centers for Disease Control. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 December 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- ↑ Kaye, Alan David; Shah, Rinoo V. (2014-10-16). Case Studies in Pain Management. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107682894.

- ↑ Hall, Helen; Cramer, Holger; Sundberg, Tobias; Ward, Lesley; Adams, Jon; Moore, Craig; Sibbritt, David; Lauche, Romy (2016). "The effectiveness of complementary manual therapies for pregnancy-related back and pelvic pain". Medicine. 95 (38): e4723. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000004723. PMC 5044890. PMID 27661020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Grace, Victoria (2000). "Pitfalls of the medical paradigm in chronic pelvic pain". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 14 (3): 527. doi:10.1053/beog.1999.0089. PMID 10962640.

- ↑ J. Curtis Nickel; Dean A Tripp; Allan Gordon; Michel Pontari; Daniel Shoskes; Kenneth M Peters; Ragi Doggweiler; Andrew P Baranowski (January 2011). "Update on Urologic Pelvic Pain Syndromes". Reviews in Urology. 13 (1): 39–49. PMC 3151586. PMID 21826127.

- ↑ Luzzi GA (2002). "Chronic prostatitis and chronic pelvic pain in men: aetiology, diagnosis and management". Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 16 (3): 253–6. doi:10.1046/j.1468-3083.2002.00481.x. PMID 12195565.

- ↑ Clemens JQ, Mullins C, Kusek JW, Kirkali Z, Mayer EA, Rodríguez LV, et al. (August 2014). "The MAPP research network: a novel study of urologic chronic pelvic pain syndromes". BMC Urol. 14: 57. doi:10.1186/1471-2490-14-57. PMC 4134515. PMID 25085007.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help)

External links

| Classification |

|---|

- Tailbone pain (coccyx pain, coccydynia) Archived 2008-10-14 at the Wayback Machine