Prothrombin G20210A

| Prothrombin G20210A | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Prothrombin thrombophilia,[1] factor II mutation, prothrombin mutation, rs1799963, factor II G20210A | |

| |

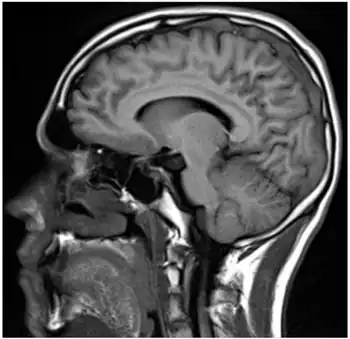

| Sagital-Prothrombin G20210A as cause of cerebral venous thrombosis | |

| Symptoms | Blood clots[1] |

| Frequency | 2% (Caucasians)[1] |

Prothrombin G20210A is a genetic condition that increases the risk of blood clots including from deep vein thrombosis, and of pulmonary embolism.[1] One copy of the mutation increases the risk of a blood clot from 1 in 1,000 per year to 2.5 in 1,000.[1] Two copies increases the risk to up to 20 in 1,000 per year.[1] Most people never develop a blood clot in their lifetimes.[1]

It is due to a specific gene mutation in which a guanine (G) is changed to an adenine (A) at position 20210 of the DNA of the prothrombin gene. Other blood clotting pathway mutations that increase the risk of clots include factor V Leiden.

Prothrombin G20210A was identified in the 1990s.[2] About 2% of Caucasians carry the variant, while it is less common in other populations.[1] It is estimated to have originated in Caucasians about 20,000 years ago.[3]

Signs and symptoms

The variant causes elevated plasma prothrombin levels (hyperprothrombinemia),[4] possibly due to increased pre-mRNA stability.[5] Prothrombin is the precursor to thrombin, which plays a key role in causing blood to clot (blood coagulation). G20210A can thus contribute to a state of hypercoagulability, but not particularly with arterial thrombosis.[4] A 2006 meta-analysis showed only a 1.3-fold increased risk for coronary disease.[6] Deficiencies in the anticoagulants Protein C and Protein S further increase the risk five- to tenfold.[2] Behind non-O blood type[7] and factor V Leiden, prothrombin G20210A is one of the most common genetic risk factors for venous thromboembolism (VTE).[4] Increased production of prothrombin heightens the risk of blood clotting. Moreover, individuals who carry the mutation can pass it on to their offspring.[8]

The mutation increases the risk of developing deep vein thrombosis (DVT),[9] which can cause pain and swelling, and sometimes post-thrombotic syndrome, ulcers, or pulmonary embolism.[10] Most individuals do not require treatment but do need to be cautious during periods when the possibility of blood clotting are increased; for example, during pregnancy, after surgery, or during long flights. Occasionally, blood-thinning medication may be indicated to reduce the risk of clotting.[11]

Heterozygous carriers who take combined birth control pills are at a 15-fold increased risk of VTE,[12] while carriers also heterozygous with factor V Leiden have an approximate 20-fold higher risk.[2] In a recommendation statement on VTE, genetic testing for G20210A in adults that developed unprovoked VTE[lower-alpha 1] was disadvised, as was testing in asymptomatic family members related to G20210A carriers who developed VTE.[13] In those who develop VTE, the results of thrombophilia tests (wherein the variant can be detected) rarely play a role in the length of treatment.[14]

Cause

| SNP: Prothrombin G20210A | |

|---|---|

| Gene | F2 |

| Chromosome | 11 |

| External databases | |

| Ensembl | Human SNPView |

| dbSNP | 1799963 |

| HapMap | 1799963 |

| SNPedia | 1799963 |

The polymorphism is located in a noncoding region of the prothrombin gene (3' untranslated region nucleotide 20210[lower-alpha 2]), replacing guanine with adenine.[4][5]

The position is at or near where the pre-mRNA will have the poly-A tail attached.[5]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of the prothrombin G20210A mutation is straightforward because the mutation involves a single base change (point mutation) that can be detected by genetic testing, which is unaffected by intercurrent illness or anticoagulant use.

Measurement of an elevated plasma prothrombin level cannot be used to screen for the prothrombin G20210A mutation, because there is too great of an overlap between the upper limit of normal and levels in affected patients.[16]

Treatment

Patients with the prothrombin mutation are treated similarly to those with other types of thrombophilia, with anticoagulation for at least three to six months. Continuing anticoagulation beyond three to six months depends on the circumstances surrounding thrombosis, for example, if the patient experiences a thromboembolic event that was unprovoked, continuing anticoagulation would be recommended. The choice of anticoagulant (warfarin versus a direct oral anticoagulant) is based on a number of different factors (the severity of thrombosis, patient preference, adherence to therapy, and potential drug and dietary interactions).[17]

Patients with the prothrombin G20210A mutation who have not had a thromboembolic event are generally not treated with routine anticoagulation. However, counseling the patient is recommended in situations with increased thrombotic risk is recommended (pregnancy, surgery, and acute illness). Oral contraceptives should generally be avoided in women with the mutation as they increase the thrombotic risk.[18]

Terminology

Because prothrombin is also known as factor II, the mutation is also sometimes referred to as the factor II mutation or simply the prothrombin mutation; in either case, the names may appear with or without the accompanying G20210A location specifier (unhelpfully, since prothrombin mutations other than G20210A are known).

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Prothrombin thrombophilia". Genetics Home Reference. Archived from the original on 13 March 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- 1 2 3 Rosendaal FR, Reitsma PH (July 2009). "Genetics of Venous Thrombosis". J. Thromb. Haemost. 7 Suppl 1: 301–304. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03394.x. PMID 19630821. S2CID 27104496.

- ↑ Kniffin, Cassandra L. & McKusick, Victor A. (2012-06-20). Coagulation factor II; F2: .0009 thrombosis, susceptibility to Archived 2022-04-21 at the Wayback Machine OMIM. Accessed January 23, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Martinelli I, Bucciarelli P, Mannucci PM (2010). "Thrombotic risk factors: basic pathophysiology". Crit Care Med. 38 (2 Suppl): S3–9. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181c9cbd9. PMID 20083911. S2CID 34486553. Archived from the original on 2020-08-09. Retrieved 2022-10-22.

- 1 2 3 Poort SR, Rosendaal FR, Reitsma PH, Bertina RM (1996). "A common genetic variation in the 3'-untranslated region of the prothrombin gene is associated with elevated plasma prothrombin levels and an increase in venous thrombosis". Blood. 88 (10): 3698–703. doi:10.1182/blood.V88.10.3698.bloodjournal88103698. PMID 8916933. Archived from the original on 2022-11-12. Retrieved 2022-10-22.

- ↑ Ye Z, Liu EH, Higgins JP, Keavney BD, Lowe GD, Collins R, et al. (2006). "Seven haemostatic gene polymorphisms in coronary disease: meta-analysis of 66,155 cases and 91,307 controls". Lancet. 367 (9511): 651–8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68263-9. PMID 16503463. S2CID 22806065.

- ↑ Reitsma PH, Versteeg HH, Middeldorp S (2012). "Mechanistic view of risk factors for venous thromboembolism". Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 32 (3): 563–8. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.242818. PMID 22345594. S2CID 2624599.

- ↑ Varga, E. A. (2004). "Prothrombin 20210 mutation". Circulation. 110 (3): e15–8. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000135582.53444.87. PMID 15262854.

- ↑ Zakai, NA; McClure, LA (October 2011). "Racial differences in venous thromboembolism". Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis (Review). 9 (10): 1877–82. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04443.x. PMID 21797965. S2CID 41043925.

- ↑ Stubbs, M J; Mouyis, Maria; Thomas, Mari (February 2018). "Deep vein thrombosis". BMJ. 360: k351. doi:10.1136/bmj.k351. ISSN 0959-8138. PMID 29472180. S2CID 3454404. Archived from the original on 2022-11-12. Retrieved 2022-10-22.

- ↑ Phillippe, Haley M.; Hornsby, Lori B.; Treadway, Sarah; Armstrong, Emily M.; Bellone, Jessica M. (June 2014). "Inherited Thrombophilia". Journal of Pharmacy Practice. 27 (3): 227–233. doi:10.1177/0897190014530390. ISSN 0897-1900. PMID 24739277. S2CID 2538482.

- ↑ Rosendaal FR (2005). "Venous thrombosis: the role of genes, environment, and behavior". Hematology Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program. 2005 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2005.1.1. PMID 16304352. S2CID 37220302.

- ↑ Evaluation of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention (EGAPP) Working Group (2011). "Recommendations from the EGAPP Working Group: routine testing for Factor V Leiden (R506Q) and prothrombin (20210G>A) mutations in adults with a history of idiopathic venous thromboembolism and their adult family members". Genetics in Medicine. 13 (1): 67–76. doi:10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181fbe46f (inactive 31 July 2022). PMID 21150787. Archived from the original on 31 October 2021. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2022 (link) - ↑ Baglin T (2012). "Inherited and acquired risk factors for venous thromboembolism". Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 33 (2): 127–37. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1311791. PMID 22648484.

- ↑ Degen SJ, Davie EW (1987). "Nucleotide sequence of the gene for human prothrombin". Biochemistry. 26 (19): 6165–77. doi:10.1021/bi00393a033. PMID 2825773.

- ↑ "UpToDate". Archived from the original on 2018-10-23. Retrieved 2022-10-22.

- ↑ Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest 2016; 149:315.

- ↑ Bauer, K.A.(2018). Prothrombin G20210A mutation. In T.W. Post, P. Rutgeerts, & S. Grover (Eds.), UptoDate. Available from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/prothrombin-g20210a-mutation?search=prothrombin%20gene%20mutation&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~103&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H3703116740 Archived 2018-01-31 at the Wayback Machine

External links

| Classification |

|---|

- Mannucci, P. M. & Franchini, M. (2015). "Classic thrombophilic gene variants". Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 114 (5): 885–889. doi:10.1160/th15-02-0141. PMID 26018405. Archived from the original (review) on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 21 May 2016.