Pulvinar nuclei

| pulvinar nuclei | |

|---|---|

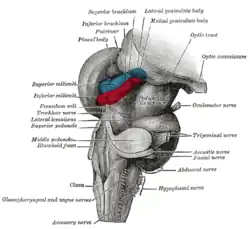

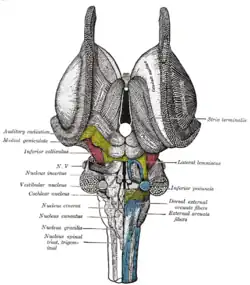

Hind- and mid-brains; postero-lateral view. (Pulvinar visible near top.) | |

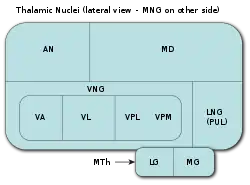

Thalamic nuclei: MNG = Midline nuclear group AN = Anterior nuclear group MD = Medial dorsal nucleus VNG = Ventral nuclear group VA = Ventral anterior nucleus VL = Ventral lateral nucleus VPL = Ventral posterolateral nucleus VPM = Ventral posteromedial nucleus LNG = Lateral nuclear group PUL = Pulvinar MTh = Metathalamus LG = Lateral geniculate nucleus MG = Medial geniculate nucleus | |

| Details | |

| Part of | thalamus |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | nuclei pulvinares (the nuclei plurally); pulvinar thalami (the set of nuclei singularly) |

| MeSH | D020649 |

| NeuroNames | 328 |

| NeuroLex ID | birnlex_824 |

| TA98 | A14.1.08.104 A14.1.08.610 |

| TA2 | 5665, 5698 |

| FMA | 62178 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

The pulvinar nuclei or nuclei of the pulvinar (nuclei pulvinares) are the nuclei (cell bodies of neurons) located in the thalamus (a part of the vertebrate brain). As a group they make up the collection called the pulvinar of the thalamus (pulvinar thalami), usually just called the pulvinar.

The pulvinar is usually grouped as one of the lateral thalamic nuclei in rodents and carnivores, and stands as an independent complex in primates.

Structure

By convention, the pulvinar is divided into four nuclei:

| TA alphanumeric identifier | TA name | English translation |

|---|---|---|

| A14.1.08.611 | nucleus pulvinaris anterior | anterior pulvinar nucleus |

| A14.1.08.612 | nucleus pulvinaris inferior | inferior pulvinar nucleus |

| A14.1.08.613 | nucleus pulvinaris lateralis | lateral pulvinar nucleus |

| A14.1.08.614 | nucleus pulvinaris medialis | medial pulvinar nucleus |

Their connectomic details are as follows:

- The lateral and inferior pulvinar nuclei have widespread connections with early visual cortical areas.

- The dorsal part of the lateral pulvinar nucleus predominantly has connections with posterior parietal cortex and the dorsal stream cortical areas.

- The medial pulvinar nucleus has widespread connections with cingulate, posterior parietal, premotor and prefrontal cortical areas.[1]

- The pulvinar also has input from the superior colliculus to inferior, lateral and medial sections, which seems to be important in the initiation and compensation of saccade,[2][3] as well as the regulation of visual attention[4][5]

Clinical significance

Lesions of the pulvinar can result in neglect syndromes and attentional deficits.[6] In addition, lesions in early life can impact normal visuomotor behaviors such as reaching and grasping.[7] Furthermore, the pulvinar was demonstrated to be instrumental in the preservation of vision afforded to a boy who lost his primary visual cortex bilaterally at birth[8] as well as other forms of blindsight in monkeys[9][10] and humans.[11] Strokes affecting the pulvinar have also been implicated in the development of chronic pain.[12]

Other animals

The pulvinar varies in importance in different animals: it is virtually nonexistent in the rat, and grouped as the lateral posterior-pulvinar complex with the lateral posterior thalamic nucleus due to its small size in cats. In humans it makes up roughly 40% of the thalamus making it the largest of its nuclei.[13] Significant research has been undertaken in the marmoset examining the role of the retinorecipient region of the inferior pulvinar (medial subdivision), which projects to visual cortical area MT, in the early development of MT and the dorsal stream, as well as following early-life lesions of the primary visual cortex (V1).[14][15][16]

Etymology and pronunciation

The word pulvinar (/pʌlˈvaɪnər/) comes to scientific English vocabulary via New Latin from classical Latin pulvinus 'cushion'. In the religion of ancient Rome, a pulvinar was an empty throne, a cushioned couch for occupation by a deity. Like the cervix uteri is usually just called the cervix (with "which cervix" being implicit), the pulvinar thalami (pulvinar of the thalamus) is usually just called the pulvinar; no other anatomic structure in today's Terminologia Anatomica is called a pulvinar,[17] although in older terminology a part of the glomus body was called the pulvinar tunicae internae segmenti arterialis anastomosis arteriovenae glomeriformis. Each pulvinar nucleus (nucleus pulvinaris) has its own set of cortical connections.

References

- ↑ Cappe C.; Morel A.; Barone P.; Rouiller E.M. (2009). "The thalamocortical projection systems in primate: an anatomical support for multisensory and sensorimotor interplay". Cerebral Cortex. 19 (9): 2025–2037. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhn228. PMC 2722423. PMID 19150924.

- ↑ Berman R.; Wurtz R. (2011). "Signals conveyed in the pulvinar pathway from superior colliculus to cortical area mt". The Journal of Neuroscience. 31 (2): 373–384. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.4738-10.2011. PMC 6623455. PMID 21228149.

- ↑ Robinson D.; Petersen S. (1985). "Responses of pulvinar neurons to real and self-induced stimulus movement". Brain Research. 338 (2): 392–394. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(85)90176-3. PMID 4027606. S2CID 7547426.

- ↑ Petersen S.; Robinson D.; Morris J. (1987). "Contributions of the pulvinar to visual spatial attention". Neuropsychologia. 25 (1): 97–105. doi:10.1016/0028-3932(87)90046-7. PMID 3574654. S2CID 23143322.

- ↑ Chalupa, L. (1991). Visual function of the pulvinar. The Neural Basis of Visual Function. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, pp. 140-159.

- ↑ Arend I.; Rafal R.; Ward R. (2008). "Spatial and temporal deficits are regionally dissociable in patients with pulvinar lesions". Brain. 131 (8): 2140–2152. doi:10.1093/brain/awn135. PMID 18669494.

- ↑ Mundinano, Inaki (2018). "Transient visual pathway critical for normal development of primate grasping behavior". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115 (6): 1364–1369. doi:10.1073/pnas.1717016115. PMC 5819431. PMID 29298912.

- ↑ Mundinano, IC; Chen, J; de Souza, M; Sarossy, MG; Joanisse, MF; Goodale, MA; Bourne, JA (2017). "More than blindsight: Case report of a child with extraordinary visual capacity following perinatal bilateral occipital lobe injury". Neuropsychologia. 128: 178–186. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2017.11.017. PMID 29146465. S2CID 207242249.

- ↑ Kinoshita M, Kato R, Isa K, Kobayashi K, Kobayashi K, Onoe H, Isa T (2019-01-11). "Dissecting the circuit for blindsight to reveal the critical role of pulvinar and superior colliculus". Nat Commun. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-08058-0. PMID 30635570.

- ↑ Takakuwa N, Isa K, Onoe H, Takahashi J, Isa T (2021-02-24). "Contribution of the Pulvinar and Lateral Geniculate Nucleus to the Control of Visually Guided Saccades in Blindsight Monkeys". J Neurosci. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2293-20.2020. PMID 33443074.

- ↑ Kletenik I, Ferguson MA, Bateman JR, Cohen AL, Lin C, Tetreault A, Pelak VS, Anderson CA, Prasad S, Darby RR, Fox MD (2021-12-27). "Network Localization of Unconscious Visual Perception in Blindsight". Annals of Neurology. doi:10.1002/ana.26292. PMID 34961965.

- ↑ Vartiainen, Nuutti; Perchet, Caroline; Magnin, Michel; Creac’h, Christelle; Convers, Philippe; Nighoghossian, Norbert; Mauguière, François; Peyron, Roland; Garcia-Larrea, Luis (March 2016). "Thalamic pain: anatomical and physiological indices of prediction". Brain. 139 (3): 708–722. doi:10.1093/brain/awv389. ISSN 0006-8950. PMID 26912644.

- ↑ LaBerge, D. (1999). Attention pp. 44-98. In Cognitive science (Handbook of Perception and Cognition, Second Edition), Bly BM, Rumelhart DE. (edits). Academic Press ISBN 978-0-12-601730-4 p. 73

- ↑ Warner CE, Kwan WC, Bourne JA (2012). "The early maturation of visual cortical area MT is dependent on input from the retinorecipient medial portion of the inferior pulvinar". Journal of Neuroscience. 32 (48): 17073–17085. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3269-12.2012. PMC 6621860. PMID 23197701.

- ↑ Warner CE, Goldshmit Y, Bourne JA (2010). "Retinal afferents synapse with relay cells targeting the middle temporal area in the pulvinar and lateral geniculate nuclei". Front Neuroanat. 4: 8. doi:10.3389/neuro.05.008.2010. PMC 2826187. PMID 20179789.

- ↑ Warner CE, Kwan WC, Wright D, Johnston LA, Egan GF, Bourne JA (2015). "Preservation of vision by the pulvinar following early-life primary visual cortex lesions". Curr Biol. 25 (4): 424–434. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.12.028. PMID 25601551.

- ↑ Baud, RH; et al., "Latin index of TA98, Terminologia Anatomica version 1998", Federative International Programme on Anatomical Terminologies (FIPAT), International Federation of Associations of Anatomists (IFAA), hosted by the University of Fribourg (Switzerland)

Additional images

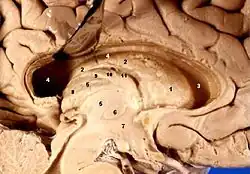

Thalamus

Thalamus Deep dissection of brain-stem. Lateral view.

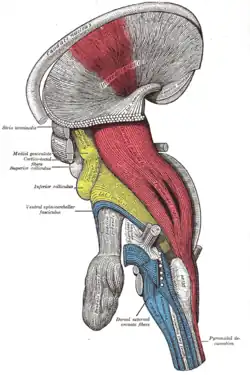

Deep dissection of brain-stem. Lateral view. Dissection of brain-stem. Dorsal view.

Dissection of brain-stem. Dorsal view. Scheme showing central connections of the optic nerves and optic tracts.

Scheme showing central connections of the optic nerves and optic tracts. Human brain left dissected midsagittal view

Human brain left dissected midsagittal view

External links

- Stained brain slice images which include the "pulvinar" at the BrainMaps project

- Atlas image: eye_38 at the University of Michigan Health System - "The Visual Pathway from Below"