Riociguat

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Adempas |

| Other names | BAY 63-2521 |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) stimulator[1] |

| Main uses | Pulmonary hypertension (PH)[1] |

| Side effects | Headache, upset stomach, nausea, diarrhea[1] |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth |

| Typical dose | 1 to 2.5 mg TID[2] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Legal | |

| License data | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 94% |

| Protein binding | 95% |

| Metabolism | CYP1A1, CYP3A4, CYP2C8, CYP2J2 |

| Metabolites | N-desmethylriociguat (active), glucuronide (inactive) |

| Elimination half-life | 5–10 h |

| Excretion | 33–45% Kidney, 48–59% Bile duct |

| Chemical and physical data | |

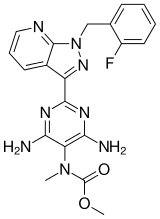

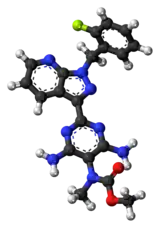

| Formula | C20H19FN8O2 |

| Molar mass | 422.424 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Riociguat, sold under the brand name Adempas is a medication used to treat two forms of pulmonary hypertension (PH): chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) and pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH).[1] It is a second line treatment.[1] It is taken by mouth.[1]

Common side effects include headache, upset stomach, nausea, and diarrhea.[1] Other side effects may include bleeding and low blood pressure.[1] Use in pregnancy may harm the baby.[1] It is a stimulator of soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC).[1]

Riociguat was approved for medical use in the United States in 2013.[1] In the United Kingdom it costs the NHS about £2,000 for 4 weeks as of 2021.[2] This amount in the United States costs about 9,500 USD.[3]

Contraindications

Riociguat can cause fetal harm and is therefore contraindicated in pregnant women.[4]

The substance is also contraindicated in pulmonary hypertension in combination with idiopathic interstitial pneumonia (PH-IIP). A clinical trial testing riociguat for this purpose was prematurely terminated because it increased severe adverse effects and mortality in patients with pulmonary hypertension caused by idiopathic interstitial pneumonia when compared to placebo.[5]

Dosage

It is started at 1 mg three times per day for the initial two weeks.[2] It may be increased up to 2.5 mg three times per day.[2]

Side effects

Serious adverse effects in clinical trials included bleeding. Hypotension (low blood pressure), headache, and gastrointestinal disorders also occurred.[4]

Interactions

Nitrates and phosphodiesterase inhibitors (including PDE5 inhibitors) increase the hypotensive (blood pressure lowering) effect of riociguat. Combining such drugs is therefore contraindicated. Riociguat levels in the blood are reduced by tobacco smoking and strong inducers of the liver enzyme CYP3A4, and increased by strong cytochrome inhibitors.[4]

Mechanism of action

In healthy individuals nitric oxide (NO) acts as a signalling molecule on vascular smooth muscle cells to induce vasodilation. NO binds to soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) and mediates the synthesis of the secondary messenger cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP). sGC forms heterodimers consisting of a larger alpha-subunit and a smaller haem-binding beta-subunit. The synthesised cGMP acts as a secondary messenger and activates cGMP-dependent protein kinase (protein kinase G) to regulate cytosolic calcium ion concentration. This changes the actin–myosin contractility, which results in vasodilation. NO is produced by the enzyme endothelial nitric oxide synthetase (eNOS). In patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension eNOS levels are reduced. This results in overall lower levels of endothelial cell-derived NO and reduced vasodilation of smooth muscle cells. NO also reduces pulmonary smooth muscle cell growth and antagonises platelet inhibition, factors which play a key role in the pathogenesis of PAH.[6] In contrast to NO- and haem-independent sGC activators like cinaciguat, the sGC stimulator riociguat directly stimulates sGC activity independent of NO[7] and also acts in synergy with NO to produce anti-aggregatory, anti-proliferative, and vasodilatory effects.[8][9]

Pharmacology

Riociguat at concentration between 0.1 and 100 μM stimulates in a dose-dependent manner sGC activity up to 73-fold. In addition, it acts synergistically with diethylamine/NO, the donor of NO, to increase sGC activity in vitro up to 112-fold.[10] A phase I study showed that riociguat is rapidly absorbed, and maximum plasma concentration is reached between 0.5–1.5 h.[11] The mean elimination half-life appears to be 5–10 hours.[11] Riociguat plasma concentrations have been also shown to be quite variable between patients, indicating that for clinical use it is probably necessary to titrate the drug specifically for each individual.

History

Discovery

The first nitric oxide (NO) independent, haem-dependent sGC stimulator, YC-1, a synthetic benzylindazole derivative, was described in 1978.[12] The characterisation 20 years later demonstrated that as well as increasing sGC activity, YC-1 acted in synergy with NO to stimulate sGC. However, YC-1 was a relatively weak vasodilator and had side effects. Therefore, the search began for novel indazole compounds that were more potent and more specific sGC stimulators. The result was the identification of BAY 41-2272 and BAY 41-8543.[13] Both compounds were tested in various preclinical studies on different animal models and appeared to improve systemic arterial oxygenation. To improve the pharmacologic and pharmacokinetic profile an additional 1000 compounds were screened leading to the discovery of riociguat.[7][14] Riociguat was tested in mouse and rat disease models, where it effectively reduced pulmonary hypertension and reversed the associated right heart hypertrophy and ventricular remodelling.

Several clinical trials have been undertaken to investigate and evaluate diverse aspects of riociguat, and some of them are still ongoing.[15]

Riociguat constitutes the first drug of the class of sGC stimulators.[16]

CHEST

The Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension sGC-Stimulator Trial (CHEST) was a randomized, placebo-controlled trial aimed to analyse the efficacy and safety of riociguat in CTEPH patients.[17]

See also

- Cinaciguat, a sGC activator (not sGC stimulator).

- PDE5 inhibitors act downstream in the nitric oxide signalling pathway, reducing cyclic GMP degradation.

- Endothelin receptor antagonist, another class of drugs used in PAH

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Riociguat Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 30 January 2021. Retrieved 17 October 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 BNF (80 ed.). BMJ Group and the Pharmaceutical Press. September 2020 – March 2021. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-85711-369-6.

- ↑ "Adempas Prices, Coupons & Patient Assistance Programs". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 10 August 2020. Retrieved 17 October 2021.

- 1 2 3 FDA Professional Drug Information

- ↑ "Adempas not for use in patients with pulmonary hypertension caused by idiopathic interstitial pneumonia". European Medicines Agency. 24 June 2016. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ↑ Giaid A, Saleh D (July 1995). "Reduced expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in the lungs of patients with pulmonary hypertension". The New England Journal of Medicine. 333 (4): 214–21. doi:10.1056/NEJM199507273330403. PMID 7540722.

- 1 2 Evgenov OV, Pacher P, Schmidt PM, Haskó G, Schmidt HH, Stasch JP (September 2006). "NO-independent stimulators and activators of soluble guanylate cyclase: discovery and therapeutic potential". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 5 (9): 755–68. doi:10.1038/nrd2038. PMC 2225477. PMID 16955067.

- ↑ Grimminger F, Weimann G, Frey R, Voswinckel R, Thamm M, Bölkow D, et al. (April 2009). "First acute haemodynamic study of soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator riociguat in pulmonary hypertension". The European Respiratory Journal. 33 (4): 785–92. doi:10.1183/09031936.00039808. PMID 19129292.

- ↑ Stasch JP, Hobbs AJ (2009). "NO-independent, haem-dependent soluble guanylate cyclase stimulators". CGMP: Generators, Effectors and Therapeutic Implications. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Vol. 191. pp. 277–308. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-68964-5_13. ISBN 978-3-540-68960-7. PMID 19089334.

- ↑ Schermuly RT, Stasch JP, Pullamsetti SS, Middendorff R, Müller D, Schlüter KD, et al. (October 2008). "Expression and function of soluble guanylate cyclase in pulmonary arterial hypertension". The European Respiratory Journal. 32 (4): 881–91. doi:10.1183/09031936.00114407. PMID 18550612.

- 1 2 Frey R, Mück W, Unger S, Artmeier-Brandt U, Weimann G, Wensing G (December 2008). "Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, tolerability, and safety of the soluble guanylate cyclase activator cinaciguat (BAY 58-2667) in healthy male volunteers". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 48 (12): 1400–10. doi:10.1177/0091270008322906. PMID 18779378. S2CID 206433961.

- ↑ Yoshina S, Tanaka A, Kuo SC (March 1978). "[Studies on heterocyclic compounds. XXXVI. Synthesis of furo[3,2-c]pyrazole derivatives. (4) Synthesis of 1,3-diphenylfuro[3,2-c]pyrazole-5-carboxaldehyde and its derivatives (author's transl)]". Yakugaku Zasshi (in Japanese). 98 (3): 272–9. doi:10.1248/yakushi1947.98.3_272. PMID 650406.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ Stasch JP, Becker EM, Alonso-Alija C, Apeler H, Dembowsky K, Feurer A, et al. (March 2001). "NO-independent regulatory site on soluble guanylate cyclase". Nature. 410 (6825): 212–5. Bibcode:2001Natur.410..212S. doi:10.1038/35065611. PMID 11242081. S2CID 4402074.

- ↑ Mittendorf J, Weigand S, Alonso-Alija C, Bischoff E, Feurer A, Gerisch M, et al. (May 2009). "Discovery of riociguat (BAY 63-2521): a potent, oral stimulator of soluble guanylate cyclase for the treatment of pulmonary hypertension". ChemMedChem. 4 (5): 853–65. doi:10.1002/cmdc.200900014. PMC 3313366. PMID 19263460.

- ↑ ClinicalTrials.gov: Riociguat Archived 13 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Background Riociguat". Bayer HealthCare. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 15 December 2009.

- ↑ Ghofrani HA, D'Armini AM, Grimminger F, Hoeper MM, Jansa P, Kim NH, et al. (July 2013). "Riociguat for the treatment of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension" (PDF). The New England Journal of Medicine. 369 (4): 319–29. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1209657. hdl:10044/1/19669. PMID 23883377. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 August 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2021.

External links

| External sites: |

|

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |

|