Senior–Løken syndrome

| Senior–Løken syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Renal dysplasia-retinal aplasia syndrome | |

| |

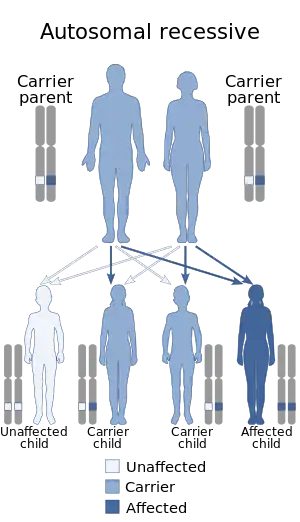

| Senior–Løken syndrome is an autosomal recessive inherited condition | |

Senior–Løken syndrome is a congenital eye disorder, first characterized in 1961.[1][2][3] It is a rare, ciliopathic, autosomal recessive disorder characterized by juvenile nephronophthis and progressive eye disease.[4]

Signs and symptoms

The presentation of this disorder, in an affected individual, is as follows:[5]

- Polyuria

- Polydipsia

- Secondary enuresis

- Anemia

- Visual loss

Genetics

Genes involved include:

| Type | OMIM | Genes |

|---|---|---|

| SLSN1 | 266900 | NPHP1 |

| SLSN3 | 606995 | unknown |

| SLSN4 | 606996 | NPHP4 |

| SLSN5 | 609254 | NPHP5/IQCB1[6] |

| SLSN6 | 610189 | NPHP6/CEP290 |

| SLSN7 | 613615 | SDCCAG8 |

Pathophysiology

The cause of Senior–Løken syndrome type 5 has been identified to mutation in the NPHP1 gene which adversely affects the protein formation mechanism of the cilia.[7]

Relation to other rare genetic disorders

Recent findings in genetic research have suggested that a large number of genetic disorders, both genetic syndromes and genetic diseases, that were not previously identified in the medical literature as related, may be, in fact, highly related in the genetypical root cause of the widely varying, phenotypically-observed disorders. Such diseases are becoming known as ciliopathies. Known ciliopathies include primary ciliary dyskinesia, Bardet–Biedl syndrome, polycystic kidney and liver disease, nephronophthisis, Alström syndrome, Meckel–Gruber syndrome and some forms of retinal degeneration.[4]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of Senior–Løken syndrome is done via the following:[5]

- Urinary analysis

- Abdominal ultrasound

- Funduscopy

- Visual acuity test

- Ocular motility

- Neurological exam

Differential diagnosis

The DDx of Senior–Løken syndrome is as follows:[5]

- Joubert syndrome with oculorenal defect

- Bardet-Biedl syndrome

- Alström syndrome

Treatment

The management of Senior–Løken syndrome has no specific therapy. However the following can be done :[5]

- Replacing loss of water/salt

- Dialysis

- Renal transplantation

References

- ↑ synd/1861 at Who Named It?

- ↑ Senior B, Friedmann AI, Brando JL (1961). "Juvenile familial nephropathy with tapetoretinal degeneration. A new oculorenal dystrophy". Am. J. Ophthalmol. 52: 625–33. doi:10.1016/0002-9394(61)90147-7. PMID 13910672.

- ↑ Loken AC, Hanssen O, Halvorsen S, Jolster NJ (1961). "Hereditary renal dysplasia and blindness". Acta Paediatrica. 50 (2): 177–84. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.1961.tb08037.x. PMID 13763238. S2CID 221396498.

- 1 2 Badano, Jose L.; Norimasa Mitsuma; Phil L. Beales; Nicholas Katsanis (2006). "The Ciliopathies: An Emerging Class of Human Genetic Disorders". Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics. 7 (1): 125–148. doi:10.1146/annurev.genom.7.080505.115610. PMID 16722803..

- 1 2 3 4 RESERVED, INSERM US14-- ALL RIGHTS. "Orphanet: Senior Loken syndrome". www.orpha.net. Archived from the original on 16 May 2023. Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- ↑ Otto EA, Loeys B, Khanna H, et al. (March 2005). "Nephrocystin-5, a ciliary IQ domain protein, is mutated in Senior-Loken syndrome and interacts with RPGR and calmodulin". Nat. Genet. 37 (3): 282–8. doi:10.1038/ng1520. PMID 15723066. S2CID 4972004.

- ↑ Davenport, James R.; Bradley K. Yoder (2005). "An incredible decade for the primary cilium : a look at a once-forgotten organelle". American Journal of Physiology. Renal Physiology. American Physiological Society. 289 (6): F1159–F1169. doi:10.1152/ajprenal.00118.2005. PMID 16275743..

External links

- OMIM: 266900 Senior-Løken syndrome; Renal dysplasia retinal aplasia; Juvenile nephronophthisis with Leber amaurosis at NIH's Office of Rare Diseases

- OMIM: 606996 Senior-Løken syndrome 4 at NIH's Office of Rare Diseases

- NCBI Genetic Testing Registry Archived 2018-12-05 at the Wayback Machine

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|