Vasa praevia

| Vasa praevia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Vasa previa |

| |

| Specialty | Obstetrics |

Vasa praevia is a condition in which fetal blood vessels cross or run near the internal opening of the uterus. These vessels are at risk of rupture when the supporting membranes rupture, as they are unsupported by the umbilical cord or placental tissue.

Risk factors include low-lying placenta, in vitro fertilization.[1]

Vasa praevia occurs in about 0.6 per 1000 pregnancies.[1] The term "vasa previa" is derived from the Latin; "vasa" means vessels and "previa" comes from "pre" meaning "before" and "via" meaning "way". In other words, vessels lie before the fetus in the birth canal and in the way. [2]

Cause

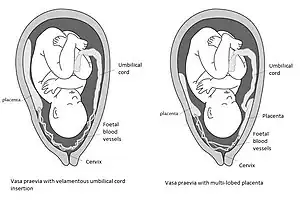

Vasa previa is present when unprotected fetal vessels traverse the fetal membranes over the internal cervical os. These vessels may be from either a velamentous insertion of the umbilical cord or may be joining an accessory (succenturiate) placental lobe to the main disk of the placenta. If these fetal vessels rupture the bleeding is from the fetoplacental circulation, and fetal exsanguination will rapidly occur, leading to fetal death. It is thought that vasa previa arises from an early placenta previa. As the pregnancy progresses, the placenta tissue surrounding the vessels over the cervix undergoes atrophy, and the placenta grows preferentially toward the upper portion of the uterus. This leaves unprotected vessels running over the cervix and in the lower uterine segment. This has been demonstrated using serial ultrasound. Oyelese et al. found that 2/3 of patient with vasa previa at delivery had a low-lying placenta or placenta previa that resolved prior to the time of delivery. There are three types of vasa previa. Types 1 and 2 were described by Catanzarite et al. In Type 1, there is a velamentous insertion with vessels running over the cervix. In Type 2, unprotected vessels run between lobes of a bilobed or succenturiate lobed placenta. In Type 3, a portion of the placenta overlying the cervix undergoes atrophy. In this type, there is a normal placental cord insertion and the placenta has only one lobe. However, vessels at a margin of the placenta are exposed.

Risk factors

Vasa previa is seen more commonly with velamentous insertion of the umbilical cord, accessory placental lobes (succenturiate or bilobate placenta), multiple gestation, and in vitro fertilisation pregnancy. In IVF pregnancies, incidences as high as one in 300 have been reported. The reasons for this association are not clear, but disturbed orientation of the blastocyst at implantation, vanishing embryos and the increased frequency of placental morphological variations in IVF pregnancies have all been postulated.

Diagnosis

- The classic triad of the vasa praevia is: membrane rupture, painless vaginal bleeding and fetal bradycardia or fetal death.

- Prior to the advent of ultrasound, this diagnosis was most often made after a stillbirth or neonatal death in which the mother had ruptured her membranes, had some bleeding, and delivered an exsanguinated baby. In these cases, examination of the placenta and membranes after delivery would show evidence of a velamentous cord insertion with rupture of the vessels. However, with almost universal use of ultrasound in the developed world, many cases are now detected during pregnancy, giving the opportunity to deliver the baby before this catastrophic rupture of the membranes occurs. Vasa previa is diagnosed with ultrasound when echolucent linear or tubular structures are found overlying the cervix or in close proximity to it. Transvaginal ultrasound is the preferred modality. Color, power and pulsed wave Doppler should be used to confirm that the structures are fetal vessels. The vessels will demonstrate a fetal arterial or venous waveform.[3][4]

- Alkali denaturation test detects the presence of fetal hemoglobin in vaginal blood, as fetal hemoglobin is resistant to denaturation in presence of 1% NaOH. Tests such as the Ogita Test, Apt test or Londersloot test were previously used to attempt to detect fetal blood in the vaginal blood, to help make the diagnosis. These tests are no longer widely used in the US, but are sometimes used in other parts of the world.

- Also detection of fetal hemoglobin in vaginal bleeding is diagnostic.

Treatment

It is recommended that women with vasa previa should deliver through elective cesarean prior to rupture of the membranes. Given the timing of membrane rupture is difficult to predict, elective cesarean delivery at 35–36 weeks is recommended. This gestational age gives a reasonable balance between the risk of death and that of prematurity. Several authorities have recommended hospital admission about 32 weeks. This is to give the patient proximity to the operating room for emergency delivery should the membranes rupture. Because these patients are at risk for preterm delivery, it is recommended that steroids should be given to promote fetal lung maturation. When bleeding occurs, the patient goes into labor, or if the membranes rupture, immediate treatment with an emergency caesarean delivery is usually indicated.[5][6]

See also

References

- 1 2 Ruiter, L; Kok, N; Limpens, J; Derks, JB; de Graaf, IM; Mol, B; Pajkrt, E (July 2016). "Incidence of and risk indicators for vasa praevia: a systematic review". BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 123 (8): 1278–87. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.13829. PMID 26694639. S2CID 43666201.

- ↑ Yasmine Derbala, MD; Frantisek Grochal, MD; Philippe Jeanty, MD (2007). "Vasa previa". Journal of Prenatal Medicine 2007. 1 (1): 2–13.Full text

- ↑ Lijoi A, Brady J (2003). "Vasa previa diagnosis and management". J Am Board Fam Pract. 16 (6): 543–8. doi:10.3122/jabfm.16.6.543. PMID 14963081.Full text

- ↑ Lee W, Lee V, Kirk J, Sloan C, Smith R, Comstock C (2000). "Vasa previa: prenatal diagnosis, natural evolution, and clinical outcome". Obstet Gynecol. 95 (4): 572–6. doi:10.1016/S0029-7844(99)00600-6. PMID 10725492. S2CID 19815088.

- ↑ Bhide A, Thilaganathan B (2004). "Recent advances in the management of placenta previa". Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 16 (6): 447–51. doi:10.1097/00001703-200412000-00002. PMID 15534438. S2CID 24710500.

- ↑ Oyelese Y, Smulian J (2006). "Placenta previa, placenta accreta, and vasa previa". Obstet Gynecol. 107 (4): 927–41. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000207559.15715.98. PMID 16582134. S2CID 22774083.