VIPoma

| VIPoma | |

|---|---|

| |

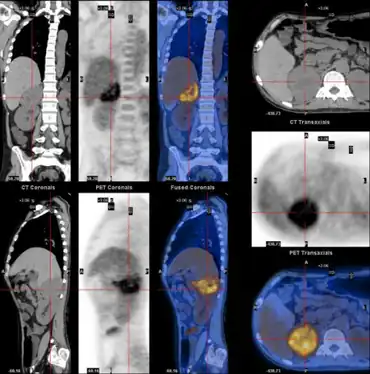

| WDHA caused by pheochromocytoma-,PET-CT scan demonstrating well defined adrenal mass | |

| Specialty | Oncology |

A VIPoma or vipoma (/vɪˈpoʊmə/) is a rare endocrine tumor[1] that overproduces vasoactive intestinal peptide (thus VIP + -oma). The incidence is about 1 per 10,000,000 per year. VIPomas usually (about 90%) originate from the non-β islet cells of the pancreas. They are sometimes associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Roughly 50–75% of VIPomas are malignant, but even when they are benign, they are problematic because they tend to cause a specific syndrome: the massive amounts of VIP cause a syndrome of profound and chronic watery diarrhea and resultant dehydration, hypokalemia, achlorhydria, acidosis, flushing and hypotension (from vasodilation), hypercalcemia, and hyperglycemia.[2][3] This syndrome is called Verner–Morrison syndrome (VMS), WDHA syndrome (from watery diarrhea–hypokalemia–achlorhydria), or pancreatic cholera syndrome (PCS). The eponym reflects the physicians who first described the syndrome.[4]

Symptoms and signs

The major clinical features are prolonged watery diarrhea (fasting stool volume > 750 to 1000 mL/day) and symptoms of hypokalemia and dehydration. Half of the patients have relatively constant diarrhea while the rest have alternating periods of severe and moderate diarrhea. One third have diarrhea < 1yr before diagnosis, but in 25%, diarrhea is present for 5 yr or more before diagnosis. Lethargy, muscle weakness, nausea, vomiting and crampy abdominal pain are frequent symptoms. Hypokalemia and impaired glucose tolerance occur in < 50% of patients. Achlorhydria is also a feature. During attacks of diarrhea, flushing similar to the carcinoid syndrome occur rarely.[5]

Cause

The etiology of VIPoma is not currently known.[6]

Diagnosis

Besides the clinical picture, fasting VIP plasma level may confirm the diagnosis, and CT scan and somatostatin receptor scintigraphy are used to localise the tumor, which is usually metastatic at presentation.[7]

Tests include:

- Blood chemistry tests (basic or comprehensive metabolic panel)

- CT scan of the abdomen

- MRI of the abdomen

- Stool examination for the cause of diarrhea and electrolyte levels

- Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) level in the blood[8]

Treatment

The first goal of treatment is to correct dehydration. Fluids are often given through a vein (intravenous fluids) to replace fluids lost in diarrhea. The next goal is to slow the diarrhea. Some medications can help control diarrhea. Octreotide, which is a human-made form of the natural hormone somatostatin, blocks the action of VIP.

The best chance for a cure is surgery to remove the tumor. If the tumor has not spread to other organs, surgery can often cure the condition.

For metastatic disease, peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) can be highly effective. This treatment involves attaching a radionuclide (Lutetium-177 or Yttrium-90) to a somatostatin analogue (octreotate or octreotide). This is a novel way to deliver high doses of beta radiation to kill tumours. Some people seem to respond to a combination chemo called capecitabine and temozolomide but there is no report that it totally cured people of VIPoma.

Prognosis

Surgery can usually cure VIPomas. However, in one-third to one-half of patients, the tumor has spread by the time of diagnosis and cannot be cured.

References

- ↑ "VIPoma" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ↑ Mansour JC, Chen H (Jul 2004). "Pancreatic endocrine tumors". J Surg Res. 120 (1): 139–61. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2003.12.007. PMID 15172200.

- ↑ "VIPoma | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2018-04-18. Retrieved 2018-04-17.

- ↑ Verner JV, Morrison AB (Sep 1958). "Islet cell tumor and a syndrome of refractory watery diarrhea and hypokalemia". Am J Med. 25 (3): 374–80. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(58)90075-5. PMID 13571250.

- ↑ "Carcinoid Tumors and Syndrome". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ↑ "VIPoma: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Archived from the original on 8 September 2021. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ↑ Sandhu S, Jialal I. "ViPoma". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 30 December 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ↑ Sandhu S, Jialal I. "ViPoma". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 30 December 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- Jensen RT, Norton JA. Endocrine tumors of the pancreas and gastrointestinal tract. In: Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ, eds. Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease . 9th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; 2010:chap 32.

- National Cancer Institute. Islet cell tumors (pancreatic) treatment PDQ. Updated October 31, 2008. Archived February 25, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |