This article was co-authored by wikiHow staff writer, Eric McClure. Eric McClure is an editing fellow at wikiHow where he has been editing, researching, and creating content since 2019. A former educator and poet, his work has appeared in Carcinogenic Poetry, Shot Glass Journal, Prairie Margins, and The Rusty Nail. His digital chapbook, The Internet, was also published in TL;DR Magazine. He was the winner of the Paul Carroll award for outstanding achievement in creative writing in 2014, and he was a featured reader at the Poetry Foundation’s Open Door Reading Series in 2015. Eric holds a BA in English from the University of Illinois at Chicago, and an MEd in secondary education from DePaul University.

There are 7 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

This article has been viewed 410,167 times.

Learn more...

Dungeons and Dragons is the most popular fantasy roleplaying game in the world. To play Dungeons and Dragons, players need to create fantasy characters, and the dungeon master needs to create a campaign. However, none of this is possible without a larger world—nations, geography, history, and conflicts. To create a world in Dungeons and Dragons, start by deciding on a scope and approach. If you want a big, sprawling world, start by designing a continent. If you want to focus on the town the characters are in, start there instead. Then, you can start adding towns, states, hierarchies, and political structures. All of this is totally up to you, and there’s no right or wrong way to do it, so have fun while you’re building a world from scratch!

Things You Should Know

- You can design from the top-down by starting with the world and large and building continents, capital cities, and political factions, or design from the bottom-up by building one town and filling in the world around it.

- Every world has conflict, so identify at least one major tension in your world for the players to explore.

- Come up with at least two unique qualities for each region, town, and area so that they stay separate and distinct in your players’ minds.

- You can always use a preexisting world (like Greyhawk or Ravnica) if you don’t enjoy worldbuilding.

Steps

Sample Campaigns

Choosing an Approach

-

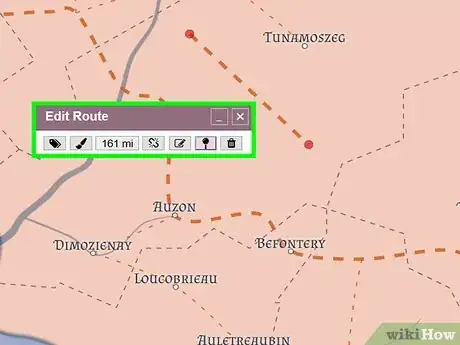

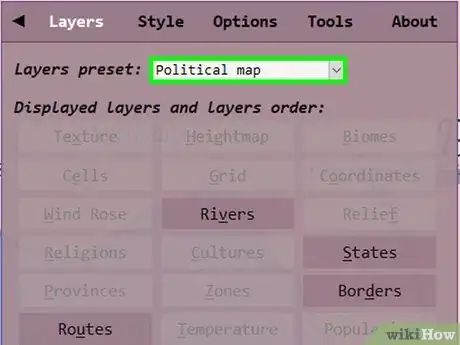

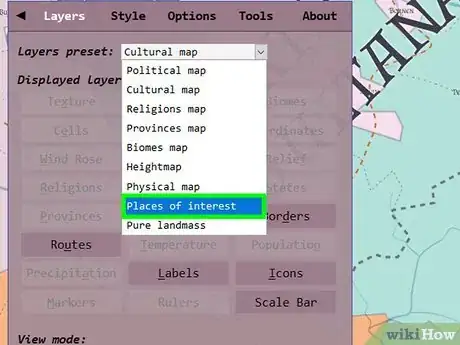

1Create a continent and work your way down if you want a sprawling campaign. If you really enjoy designing, drawing, and writing, start with a world map and work your way down. You can draw one from scratch, or use an online program to construct one. Name the states or nations and pick capital cities. Pick where you’re going to start your players out at and work your way out from there.[1]

- The major disadvantage of this approach is that it’s a lot of work. Naming, designing, and populating an entire continent is a lot of work up front, and some dungeon masters will spend months crafting an entire world.

- The major advantage of this approach is that your world will feel intricate, real, and rich. When players ask a character a question about the world, you’ll have an answer that will feel real and prepared. It will also be easier to stay consistent, since you’ll have thought through the entire world well in advance of the game.

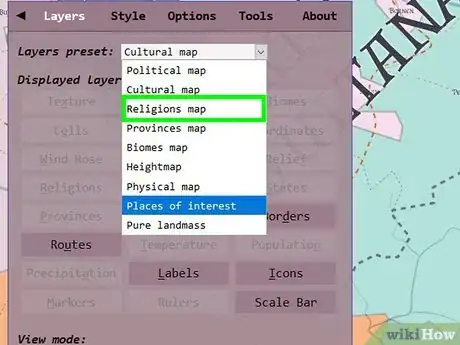

- Look online for inspiration. Inkarnate is a popular map-making service, and can be found at https://inkarnate.com/. You can make a randomly-generated map online at https://azgaar.github.io/Fantasy-Map-Generator/.

-

2Start with the starting town and work your way up to make the world more focused. If you want your players focusing their attention in one area, start with the town or area where your players are starting out and work your way out from there. Come up with a name for the town, and design a sheriff, mayor, and tavern. When players ask about the outside world, make the answers vague to create a sense that the characters know just as much as the players do.[2]

- The major disadvantage of this approach is that you’ll have to improvise a lot. When players venture out into uncharted territory, you’ll be scrambling to figure out who lives there, how long they’ve been there, and what they want.

- The major advantage of this approach is that your scope will be focused. When players want to know about a new area, they’ll have to put in some effort to go there instead of relying on outlying information. This can make in-game decisions feel heavy and important.

Advertisement -

3Avoid railroading as you’re building your world by including options. Railroading refers to the act of removing choice from the players. This could mean that part of the map is off-limits, or a town is unreachable for no real reason. It could also mean that your world has too many rules. Maybe a town has too many guards or walls. Keep as many options open to the players as possible so that they feel like they’re a part of the world.[3]

- Dungeon masters often unintentionally railroad their players when they really want them to go somewhere. Avoid doing this as often as possible, even if you really want the players to experience something. You can always move an encounter at the last minute!

- Player choice is essential to creating a fun world. Don’t start your players off in the bottom of a pit with no way to get out.

- Players will take unexpected routes, and they may not go where you want. You have to be able to improvise and roll with it. Don’t say, “No,” just because you aren’t prepared.

-

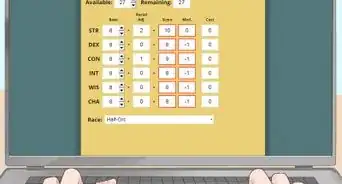

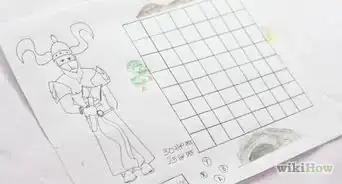

4Keep track of all of the background information in a single document. Every time that you work on your world, add it to the document. Before the first game, print the entire document and refer back to it as you play. If you ever need to add to it, simply print the additional pages and staple them to the back.[4]

- It is not unusual (or bad game management) for a dungeon master to say “hold on a second,” and flip back a few pages to answer a question accurately.

Tip: To make a world feel cohesive, try to avoid going back and changing things too often. If you say that a King’s name is “Arrgarth” and then think of a cooler name later, your world will feel cheap and flimsy if you change it after the players met the king. It’s better to build the changes you want into the story. Maybe that badly-named King gets assassinated after meeting the players!

Designing a Larger World

-

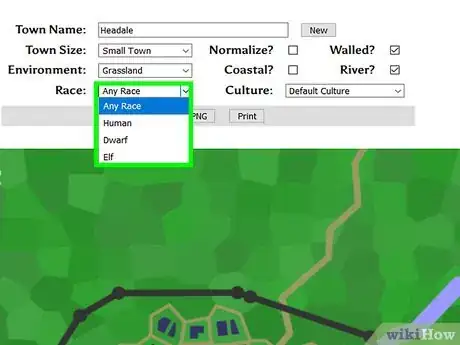

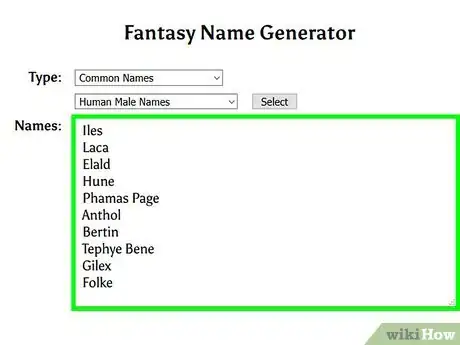

1Name your major states and determine who lives there. Choose names for your states and major cities and determine the demographics and type of people that live there. Make the names reflect the tone and demographics of the city. For example, a human trading city might be named “Elmshire” while the neighboring orc village full of mercenaries might be called “Verzanzibu,” which sounds a little more foreign and dangerous.[5]

- Be careful if you’re trying to make a serious campaign. A dangerous city named “Flufftown” is going to seem ridiculous to your players.

- You can make mixed-race cities! They tend to be stable and focused on trading in most campaigns.

- If you need inspiration, visit https://azgaar.github.io/Fantasy-Map-Generator/ or https://donjon.bin.sh/fantasy/town/ for ideas and names.

Tip: The major races in Dungeons and Dragons are Humans, Elves, Half-Elves, Dwarves, Gnomes, Orcs, Dragonborn (which are like dragon people), Goblins, and Halflings. These races tend to have their own societal structures, focuses, and motivations.

-

2Choose which conflicts are taking place in the background. Whether 2 nations are at war or there’s a military coup taking place, a background conflict will give your world a sense of realism. Choose 1 or 2 conflicts that are taking place in the background so that the players feel like they’re a part of a world that is bigger than they are.[6]

- Other conflicts could include a nation trying to take over the world, political infighting, or social unrest. Draw on real-world events for inspiration!

- Conflicts are a good way to make locations seem like they’re evolving. If there’s religious persecution taking place in a town, maybe one side won while the players were away! This will give player inaction a sense of consequence and encourage them to get involved in local affairs.

-

3Come up with at least 2 notable qualities for every state and capital city. If you don’t come up with a few unique characteristics for each location, they’ll start to feel stale, cold, and repetitive to the players. Maybe one location has rolling hills and a fungus infestation while another area is known for having torrential downpours and bear attacks. One city could be known for having rigid laws and tall castles while another city could have a problem with gangs and illegal trade.[7]

- Unique qualities for cities could relate to the architecture, laws, social structure, norms, or demographics.

- Interesting traits for states could relate to the geography, wildlife, foliage, or weather.

-

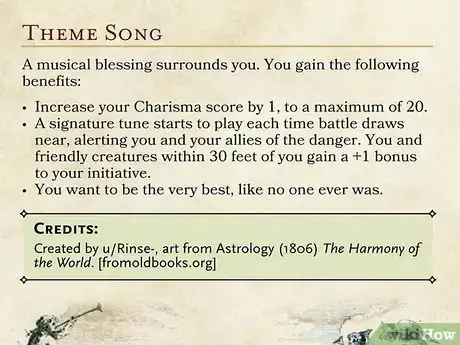

4Decide how important you want religion to be in your world. Gods are an important part of the Dungeons and Dragons lore, but they can radically change the layout of the game if you’re designing a world from scratch. Consider how many gods you want to include in your world. If you think gods and magic make for great plot devices, use a lot of gods! It’s okay to leave a bunch of them out as well.[8]

- For example, if religion is really important in your world, you’ll need a detailed list of deities. You’ll need to put temples in your towns, and clerics have to pray to specific gods.

- You can use religion to generate a conflict in your world without relying on player decisions. This can be helpful if you really want something to happen in-game, but don’t have a good reason based on player behavior.

Creating a Town

-

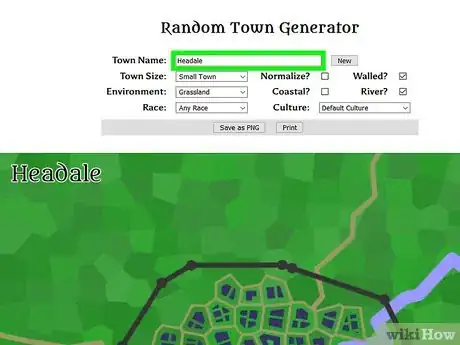

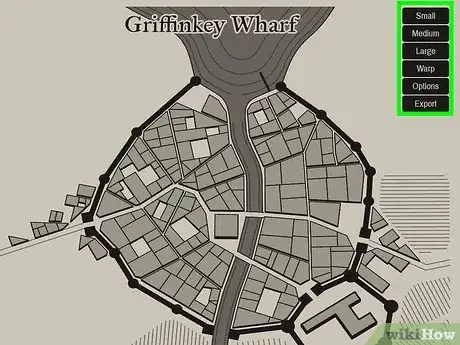

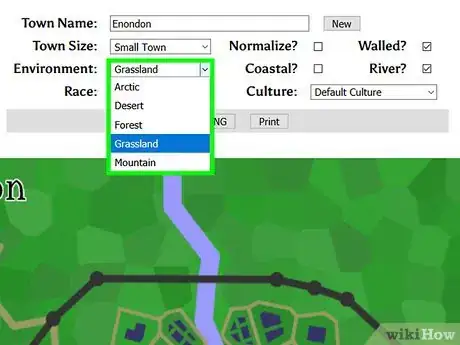

1Create a map for your town to give players a sense of location. Players are going to want to know where they are, where they entered the city, and where the main buildings are located. Draw a map or generate one online to share with your players. A map will make the roleplaying feel more authentic and will make it easier for your players to become attached to a place.[9]

- Visit https://watabou.itch.io/medieval-fantasy-city-generator to randomly generate a town map.

-

2Choose a mayor and political structure for the town. Every NPC that lives in a town would know the mayor’s name and what life is like in that city or village. Give your mayor a name and select a political structure for the city. Whether they hold democratic elections or have been under the thumb of a noble family for centuries, there has to be a guiding structure for the city. Pick a government based on the vibe you want to create for that town.[10]

- Consider how laws are enforced in your town. A totalitarian government is probably going to have secret police and random searches, while a peaceful trading city will likely have open-air markets and lots of shops.

-

3Create 1 or 2 colorful NPCs for the players to interact with. Every city has its local legends. Create 2 NPCs (non-player characters) and give them names. Choose motivations for your NPCs and think about where the party could find them. Memorable characters will make your players feel like they’re attached to something in the city, and could motivate them to become involved in a local conflict.[11]

- NPC is shorthand for non-player character. It is a general term for any in-game individual that isn’t controlled by the players. NPCs can be friendly, rude, aggressive, or greedy just like any player-character (or PC).

- For example, a town could have a well-known drunkard who hangs out at the local tavern and does magic. Maybe he gets into arguments with a goofy sheriff who has a handlebar moustache and offers money to people that offer to help track bandits. This gives your party something to get involved in as soon as they get into town!

- Good motivations include the desire for power, money, or the destruction of a rival. Maybe a character is just trying to have a good time!

Tip: Assign an accent to an NPC when you’re speaking as them. This will give them some color and make it easier for the party to remember who they’re talking to.

-

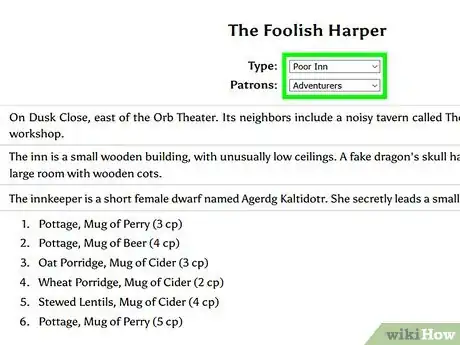

4Create a tavern or inn for the party to visit. Every town needs a tavern or inn—the staple institutions of a good fantasy town. Choose names for the tavern like, “The Fairy Mother’s,” or, “The Drunken Sailor,” based on the vibe you’re trying to create. Good names for an inn might be, “River Stone Lodging,” or “The Early Bird.”

- You can combine the 2 buildings to create a tavern and inn to make things easy.

- You absolutely need an inn if the players are going to sleep somewhere. This is important from a game perspective because resting is how players regain hit points and spells.

- Visit https://donjon.bin.sh/d20/magic/shop.html to randomly generate names and inventories for shops, taverns, and inns.

- Players need to eat! What’s on the menu at the local tavern? Come up with a few fantasy menu items, like ham soup, Dwarven ale, boar leg, or shrub salad.

-

5Design shops so that your players can trade loot and buy items. Your players need something to do with all the gold and treasure that they acquire over the course of a game. Put a shop in each town that you design and have them sell different kinds of items to give each town an identity. One town’s shop could sell weapons while another town’s shop might focus in rings and magic robes.[12]

- Good names for shops might be, “The Treasure Chest,” or, “The Wizard’s Robes.”

- Shopkeepers can make for fun NPCs. Give each shop a memorable character running it.

- You can find a randomly-generated list of store goods at https://www.realmshelps.net/stores/store.shtml.

- Be careful when creating a shop with too many powerful items. If your players rob the store, they’ll be overpowered.

Modifying Preexisting Worlds

-

1Borrow official maps or find maps others have made online. It is common in the Dungeons and Dragons community to share maps and homemade materials for others to use. Wizards of the Coast, the company that owns Dungeons and Dragons, also publishes materials for players to borrow for world-building. Look online for maps and worlds that you can use and modify them as you please to make things easier.[13]

- Major online communities that share homemade maps for others to use include https://www.reddit.com/r/UnearthedArcana/, https://www.dndbeyond.com/forums/dungeons-dragons-discussion/, and https://www.reddit.com/r/d100/.

- You can find official Dungeons and Dragons maps at https://dnd.wizards.com/ in the “Story” tab.

Tip: Forgotten Realms and Greyhawk are the 2 most popular worlds, and there will be a lot of campaign materials out there for these worlds. Other popular choices include Eberron, The Outlands, and Ravenloft.

-

2Use the deities published in the Dungeons and Dragons texts for your pantheon. Creating your own pantheon of deities can be an overwhelming task. Use the preexisting list of gods, angels, and devils as a reference to make it easier to keep track of all of the gods. Visit https://www.dndbeyond.com/sources/basic-rules/appendix-b-gods-of-the-multiverse for the list of gods in the game.[14]

- The gods in Dungeons and Dragons are listed as either “major deities” or “minor deities.” Minor deities tend to be less powerful, and major deities typically have temples in major cities.

- Like players and NPCs, gods have their own alignments. A chaotic-evil god may want its followers to attack the innocent, while a god that is lawful good likely wants its followers to build shelters and engage in charity.

-

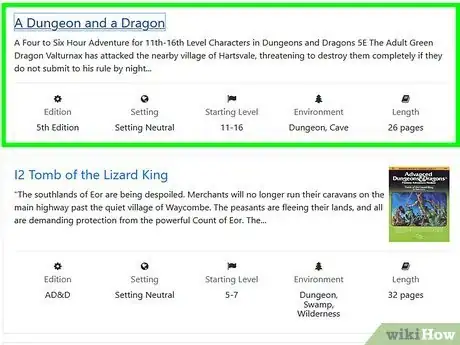

3Run an entirely prefabricated campaign if you dislike world-building. If designing a world seems uninteresting or you’re short on time, there’s nothing wrong with playing a world that already exists. You can find entire campaigns in the Dungeons and Dragons supplemental books. Many are listed online at https://www.adventurelookup.com/adventures/ or https://dnd.wizards.com/ in the “Story” tab.[15]

- Most campaigns are designed for 5th edition, which is a specific ruleset. If you’re playing a different version of the game, you may need to make your own campaigns or look harder for materials.

- Worlds that are made entirely from scratch are known as “homebrews” in the Dungeons and Dragons community.

Community Q&A

-

QuestionShould I specify towns and every NPC that lives there?

Community AnswerTowns should be specified, but you don't have to list every NPC that lives there. Make a storage of assorted NPCs that you can throw in whenever you so desire or when you find them necessary.

Community AnswerTowns should be specified, but you don't have to list every NPC that lives there. Make a storage of assorted NPCs that you can throw in whenever you so desire or when you find them necessary. -

QuestionHow do I make a monster?

Community AnswerTake the stats from a similar monster in the book and use them as a base for your new monster. Add or remove whatever qualities you want to make the monster unique.

Community AnswerTake the stats from a similar monster in the book and use them as a base for your new monster. Add or remove whatever qualities you want to make the monster unique. -

QuestionIs it better to have the monsters as cards in a deck for easy storage, or no cards at all and 3D models instead?

Community AnswerI have tried both of these methods, and they both work really well. I would suggest using cards because it helps show that YOU made the adventure and characters. What I did was bend them to help them stand. The side facing the adventurers had the picture of the monster and weapon, and the side facing me had its stats, making it easier on me and my players. They were also easier to store, and much cheaper.

Community AnswerI have tried both of these methods, and they both work really well. I would suggest using cards because it helps show that YOU made the adventure and characters. What I did was bend them to help them stand. The side facing the adventurers had the picture of the monster and weapon, and the side facing me had its stats, making it easier on me and my players. They were also easier to store, and much cheaper.

References

- ↑ https://critical-hits.com/blog/2010/12/01/the-architect-dm-world-building-basics/

- ↑ https://critical-hits.com/blog/2010/12/01/the-architect-dm-world-building-basics/

- ↑ https://critical-hits.com/blog/2010/12/01/the-architect-dm-world-building-basics/

- ↑ https://critical-hits.com/blog/2010/12/01/the-architect-dm-world-building-basics/

- ↑ http://www.dnd.kismetrose.com/DMTypesofPlaces.html

- ↑ http://www.dnd.kismetrose.com/DMTypesofPlaces.html

- ↑ http://www.dnd.kismetrose.com/DMTypesofPlaces.html

- ↑ https://www.dndbeyond.com/sources/basic-rules/appendix-b-gods-of-the-multiverse

- ↑ https://geekandsundry.com/6-tools-to-help-you-build-your-own-rpg-map/

About This Article

To create a Dungeons and Dragons campaign, start by devising a plot with a central conflict, like an assassination or natural disaster. Next, use simple shapes and labels to draw the field of battle, which can occur anywhere you choose. Then, establish setting details that affect how the characters approach the situation, such as the ability to use jungle vines to move around a jungle setting, and be sure to include unsafe terrain. Finally, set the challenge rating to establish the campaign's difficulty level. For more tips on drawing battle maps, read on!