This article was co-authored by Bryce Warwick, JD. Bryce Warwick is currently the President of Warwick Strategies, an organization based in the San Francisco Bay Area offering premium, personalized private tutoring for the GMAT, LSAT and GRE. Bryce has a JD from the George Washington University Law School.

There are 13 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

This article has been viewed 61,949 times.

Arguments based on logic can help sway others toward your point of view. Various situations in your academic, professional, and personal life will require you to be able to make a logical argument. Using a well-researched thesis, a good formula, and statements free of logical fallacies (or errors in logic) will help you win arguments and gain supporters.

Steps

Researching the Thesis

-

1Select your thesis. Your thesis is the theory you’re attempting to prove.[1] Choose something that is debatable, and be as specific as possible. For example, instead of saying, “Pollution is bad for the environment,” which is not debatable, say, “To reduce pollution, the government should tax car owners more heavily.”[2]

- Try not to be combative or confrontational in your thesis. Don’t use words like stupid or evil, which can quickly alienate the people you’re trying to convince.

- It may also be helpful to present both sides of the argument in a neutral and objective way early in your presentation.

-

2Find reliable sources that support your thesis. Seek out a librarian at your local library and ask them to help you find books and journals that relate to your research. If you are putting together an assignment for a class, your teacher may be able to provide sources, as well. You can also do much of your research online, but you’ll need to be careful about which sites you’re using. Some are more reliable than others.[3]

- Government or university websites, peer-reviewed journals, well-known news publications, or documentaries are good places to start.

- In general, social media posts, personal websites, and collaborative websites where anyone can make changes are not reliable sources to cite. These are, however, a good place to gain a basic understanding of a topic. They might also cite more reliable sources that you can use.

- Avoid sources that are trying to sell you something, since their claims may not be completely honest.

Advertisement -

3Find reliable sources that support the counterargument. Research an opposing viewpoint so that you can anticipate the arguments someone else will make against your thesis. This will also help you prepare for your response to the counterargument.[4]

- Try imagining what someone who disagreed with you would say. For example, if you’re arguing for taxing drivers in order to reduce pollution, research the ways in which taxes can have a negative impact on society.

Formulating the Argument

-

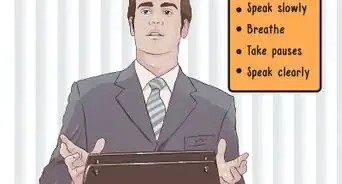

1Introduce your argument. Start with an introduction that explains what you’re going to argue. The introduction will include your thesis, and it will give a preview of how you plan to prove it. This “preview” will essentially be a brief summary of your research findings. It should also include an engaging opening sentence and a brief summary of both sides of the argument.[5]

- An example would be, "Since the 1980s, vehicle use in the our country has increased dramatically, contributing to a corresponding increase in air pollution. Several countries facing similar issues have imposed emissions taxes on car owners in an effort to combat this problem. Opponents of a vehicle emission tax have suggested that such a measure would disproportionately impact poor vehicle owners. By presenting the financial, cultural, and environmental changes in Pleasantville following the addition of their automobile tax, however, I will show that a vehicle tax is a realistic and economically sustainable option for reducing pollution in our country."

-

2Start with your strongest evidence. Begin with your most compelling piece of evidence in order to begin convincing others of your viewpoint as quickly as possible. From there, you can work your way down until you end with what you view as the weakest aspect of your argument. Alternatively, you might present your weakest point next, then finish with a slightly stronger piece of evidence.[6]

- The best piece of evidence is usually statistical. For example, "The number of cars purchased in Pleasantville went down by 8% after an additional tax was added to car purchases."

-

3Use deductive or inductive reasoning. This is the path you will take to reach your conclusion. With deductive reasoning, you will start with generalizations and then make a specific conclusion. With inductive reasoning, you will start with specifics and then make a more general conclusion.[7]

- Example of deductive reasoning: "All cars run on gas. A Toyota is a type of car. Therefore, a Toyota runs on gas." By this reasoning, if the first 2 premises are true, the third one must be true.

- Example of inductive reasoning: "My car has bad gas mileage. Some cars with bad gas mileage are banned in Pleasantville. Therefore my car will be banned in Pleasantville." By this reasoning, if the first 2 premises are true, the third one might be true, or it might not. Inductive reasoning is typically used in cases that require some prediction.

-

4Determine validity and soundness. A valid argument is one in which, if all premises are true, the conclusion must be true. Soundness refers to whether the premises are actually true. Be sure that your argument is both valid and sound.[8]

- For example, "All cars are purple. Purple cars run on gas. Therefore all cars run on gas." If all premises were true, the conclusion would be true, so it is valid. But obviously not all cars are purple, so the argument is not sound.

-

5Restate your argument in a conclusion. Conclude your argument by again summarizing what your main evidence was and how it proved your premise. Do not repeat the thesis exactly; try to rephrase it in another way.[9]

- For example, "The success of the Pleasantville auto tax in reducing car purchases, and therefore decreasing the amount of gas emissions there, demonstrates why our country needs to add a car tax to our environmental efforts."

- You can use the conclusion as a chance to reemphasize why your argument matters, but do not introduce any new evidence or information here.

- If you like, you might end with an engaging “hook” that mirrors your opening lines. For example, if you started your essay with a quote, end with a similar or related quote.

Avoiding Logical Fallacies

-

1Avoid hasty generalizations. These are claims made without sufficient evidence. Don’t rush to judgement without having all the facts. Making assumptions about large groups of people will undermine your argument and potentially offend others.[10]

- For example, “All people who own cars don’t care about the environment.”

-

2Be careful of circular arguments. This is when you restate an argument while in the process of trying to prove a claim. Watch for statements in which you're basically just saying the same thing twice.[11]

- For example, “Cars contribute to pollution by polluting the environment.”

-

3Refrain from begging the claim. This is when you reword the claim as support for the claim. It's similar to a circular argument, though it may use more prejudicial language. Use specific evidence to help prove your point rather than biased descriptions.[12]

- For example, “Poisonous gas fumes are polluting the Earth.” Prove how the fumes are causing pollution, rather than calling them poisonous.

-

4Steer clear of ad hominem arguments. Don’t attack a person’s character rather than their arguments or positions on certain issues. A person's character is unrelated to the issue at hand, and it makes you look biased against that person.[13]

- For example, “John’s plan won’t solve anything because he’s selfish.” This doesn’t address anything about John’s plan or how it affects the issue; it only attacks him personally.

-

5Avoid red herring arguments. This is when you try to divert attention from something and, in doing so, avoid the key issues you should be addressing.[14]

- For example, “Think of how much faster your commute will be if there are fewer cars on the road!” This doesn’t have anything to do with the environmental impact of cars or the economic impact of taxes.

-

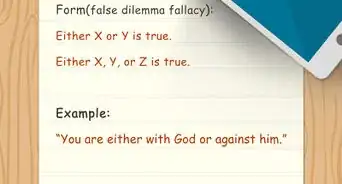

6Try not to make either/or arguments. This oversimplifies an argument by insisting there are only 2 choices. There are almost always more than 2 options when facing a problem, so don’t assume yours is the only solution (however, keep in mind that there are always exceptions). Present a strong case for your argument rather than scaring others into thinking it's the only way.[15]

- For example, “We can either tax car owners or destroy the planet.”

Expert Q&A

Did you know you can get expert answers for this article?

Unlock expert answers by supporting wikiHow

-

QuestionHow do I make a strong argument?

Bryce Warwick, JDBryce Warwick is currently the President of Warwick Strategies, an organization based in the San Francisco Bay Area offering premium, personalized private tutoring for the GMAT, LSAT and GRE. Bryce has a JD from the George Washington University Law School.

Bryce Warwick, JDBryce Warwick is currently the President of Warwick Strategies, an organization based in the San Francisco Bay Area offering premium, personalized private tutoring for the GMAT, LSAT and GRE. Bryce has a JD from the George Washington University Law School.

Test Prep Tutor, Warwick Strategies

References

- ↑ Bryce Warwick, JD. Test Prep Tutor, Warwick Strategies. Expert Interview. 5 November 2019.

- ↑ https://writingcenter.fas.harvard.edu/pages/developing-thesis

- ↑ https://www.ourcommunity.com.au/advocacy/advocacy_article.jsp?articleId=2413

- ↑ http://writingcenter.unc.edu/handouts/argument/

- ↑ https://owl.english.purdue.edu/engagement/2/2/55/

- ↑ http://penandthepad.com/5-parts-essay-8406914.html

- ↑ http://www.livescience.com/21569-deduction-vs-induction.html

- ↑ http://www.iep.utm.edu/val-snd/

- ↑ http://penandthepad.com/5-parts-essay-8406914.html

- ↑ https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/659/03/

- ↑ http://www.logicalfallacies.info/presumption/begging-the-question/

- ↑ https://www.logicallyfallacious.com/tools/lp/Bo/LogicalFallacies/53/Begging_the_Question

- ↑ https://www.logicallyfallacious.com/tools/lp/Bo/LogicalFallacies/9/Ad-Hominem-Circumstantial

- ↑ https://literarydevices.net/red-herring/

- ↑ https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/659/03/