This article was co-authored by wikiHow staff writer, Luke Smith, MFA. Luke Smith is a wikiHow Staff Writer. He's worked for literary agents, publishing houses, and with many authors, and his writing has been featured in a number of literary magazines. Now, Luke writes for the content team at wikiHow and hopes to help readers expand both their skillsets and the bounds of their curiosity. Luke earned his MFA from the University of Montana.

There are 9 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

This article has been viewed 1,988 times.

Learn more...

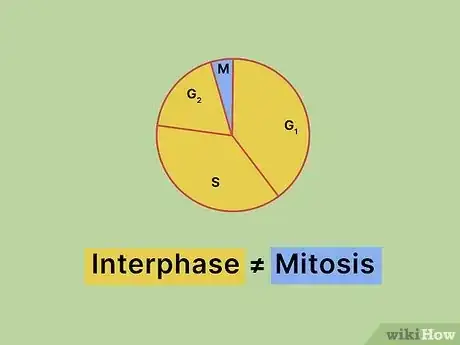

There are trillions of cells in your body, and those cells are constantly making more cells in a process we call the “cell cycle.” The cell cycle has a number of phases, but is made up of 2 primary phases: interphase and mitosis. But what happens during each phase? And how long does it all take? We’ve put together a simple cheat sheet that’ll fill you in on the longest phase of the cell cycle, then give you a quick survey of the rest of it.

Things You Should Know

- Interphase is the longest phase of the cell cycle, and has 3 subphases: G1, S-Phase, and G2.

- G1 is the longest phase of the interphase period.

- During interphase, the cell prepares itself for the next round of cell division.

- During mitosis, the cell actively divides to create two identical daughter cells.

Steps

Interphase

-

1Interphase is the longest phase of the cell cycle. During this phase, the cell prepares to divide. It includes 3 subphases (G1, S-phase or Synthesis, and G2), and these three phases make up most of the cell’s time. Of the three subphases , G1 is the longest phase.[1]

- Different types of cells take different amounts of time to undergo the cell cycle. A human cell completes its cycle about once every 24 hours.[2]

-

2G1 G1 is the first gap phase, and is the longest portion of interphase. This phase comes after the cell has completed mitosis, or division, and occurs before it begins to prepare for another division. Think of it as a little break when the cell catches its breath. After G1, the cell might either leave the cell cycle and stop dividing, or it can enter S-phase.[3]

- In human cells, G1 can last about 11 hours.[4]

Advertisement -

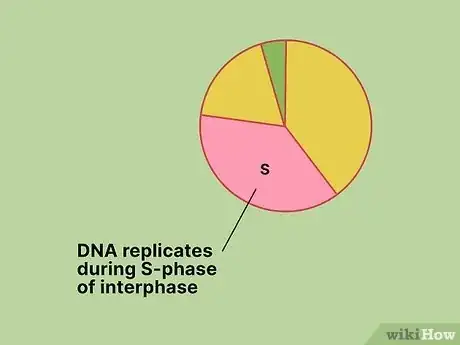

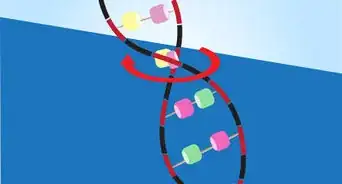

3S-Phase The cell replicates its DNA during S-phase. Before a cell can divide, it needs to make another set of DNA to give the new cell. This occurs during S-phase, when the cell’s DNA is unzipped down the center. Then, an enzyme reads the unzipped DNA and builds another DNA strand based on the existing strand.[5]

- S-phase is also a cell cycle “checkpoint,” or a moment during the cycle where the cell checks in and makes sure things are going as planned. If they’re not, the cell will cancel mitosis and begin “apoptosis” instead, which is like a built-in self-destruct process.

- In human cells, S-phase takes about 8 hours.[6]

-

4G2 G2 is the safety check before mitosis. During G2, the cell makes sure that the DNA it replicated during S-phase is all correctly assembled. Then, it makes all the proteins and extra organelles that will be given to the new cell. Once all the preparations are made, the cell moves from G2 into mitosis.[7]

- In human cells, G2 lasts about 4 hours.[8]

Mitosis

-

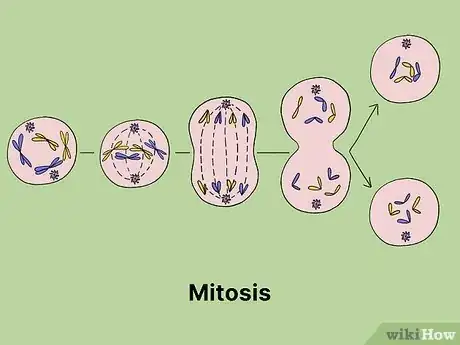

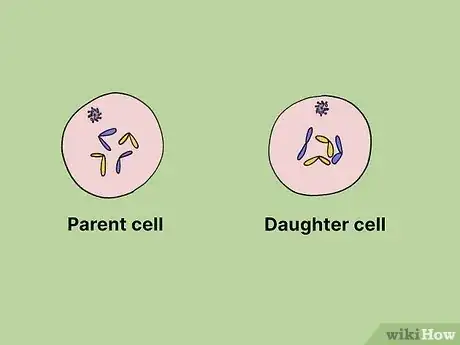

1Mitosis is the other phase of the cell cycle. In mitosis, the cell actively divides into 2 identical daughter cells. Mitosis has 4 subphases: prophase (and prometaphase), metaphase, anaphase, and telophase. Cytokinesis is also a process that occurs during mitosis. After mitosis, the cell enters interphase again and prepares for its next division.[9]

-

2

-

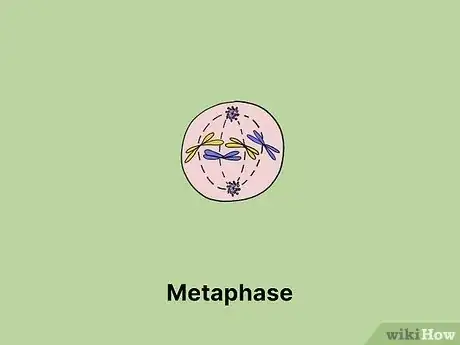

3Metaphase In metaphase, the chromosome spindle fibers are completed. Then, the chromosomes all line up at the center of the cell to prepare for cell division.[12]

-

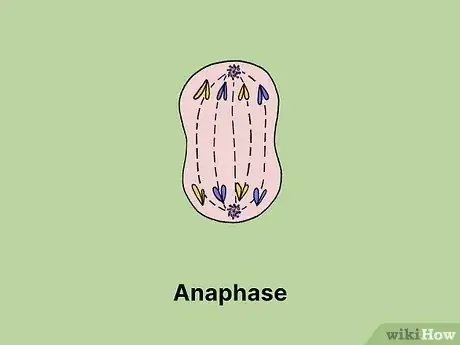

4Anaphase During anaphase, the chromosomes begin to move along the spindles. Each half of the chromosome migrates to opposite sides of the cell, and the cell elongates in preparation for the split.[13]

-

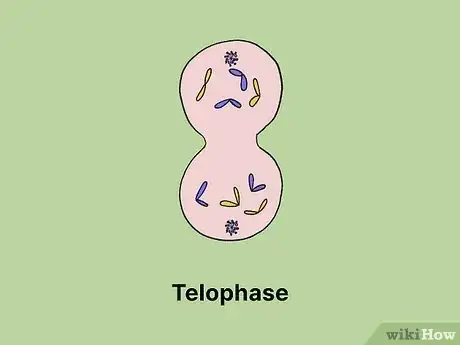

5Telophase The chromosomes finish their move in telophase. At the same time, 2 new nuclei form—one for each cell. The spindle fibers dissolve, then a new cell membrane forms along the center of the cell, walling the cells off from each other and forming two new, identical daughter cells. Then, the daughter cells enter interphase, and the cycle starts again.[14]

-

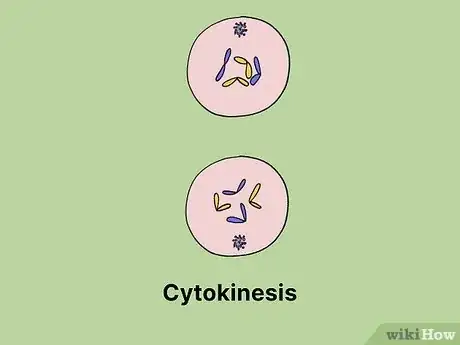

6Cytokinesis Cytokinesis is the term for the physical splitting of a cell during cell division. It happens at the same time as mitosis, starting with anaphase and ending with telophase. It simply describes the actual motion of the cell—how the cell physically moves and is shaped as it splits.[15]

Cancer Cells

-

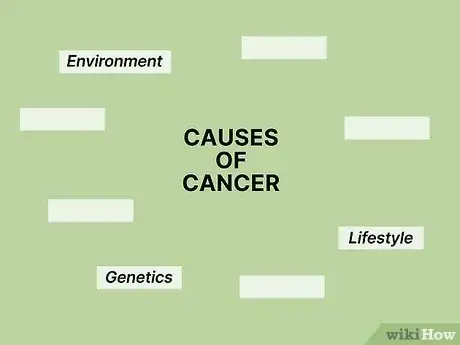

1Cancer cells are cells that multiply without regulation. They begin with a mutation within a cell, and then that mutation can grow and evolve as the cell replicates and passes on its DNA. Whereas most cells would self-destruct in the event of a serious mutation, the mutations cancer cells possess let them evade apoptosis, or voluntary cell death.[16]

-

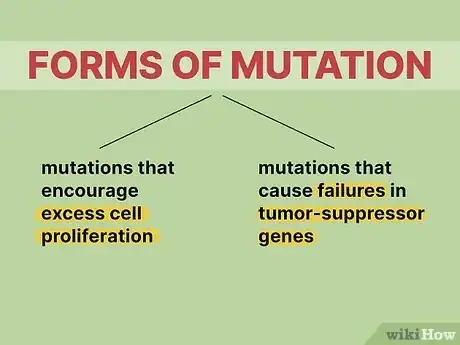

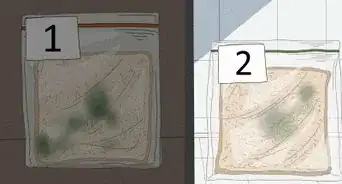

2Cancer cells are the result of errors in DNA copying. Occasionally, a cell might make a mistake as it replicates its DNA and cause a mutation in its genes. These mutations typically come in 2 forms: mutations that encourage excess cell proliferation, causing rapid and uncontrolled cell growth; and mutations that cause failures in tumor-suppressor genes, which monitor and keep cell growth in check.[17]

Common Misconceptions

-

1Interphase is distinct from mitosis. The two phases are separate, and alternate during the cell cycle. Both are parts of the cycle, but they aren’t the same and they don’t overlap.[18]

-

2Daughter cells have the same number of chromosomes as the parent cell. Though daughter cells form during a split of the parent cell, they have the same number of chromosomes. This is because the DNA is duplicated in the S-phase, and then split during mitosis. In other words, it doubles, and then it halves, and so both daughter cells have complete sets of chromosomes.[19]

-

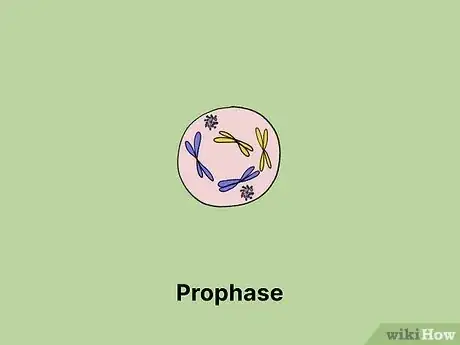

3DNA replicates during interphase, not prophase. It can be a little confusing because the names are similar, but DNA is copied during the S-phase of interphase. During prophase, the DNA merely forms pairs of chromosomes.[20]

-

4Cancer has a number of causes, not just genetics. Just because your parent or grandparent has or had cancer, it doesn’t mean you will, too. But cancer can also develop without any genetic indicators. It’s merely a mutation during cell replication and can be dependent on things like the environment and a person’s lifestyle.[21]

References

- ↑ https://sciencing.com/stages-typical-cell-cycle-6160435.html

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK9876/

- ↑ https://sciencing.com/stages-typical-cell-cycle-6160435.html

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK9876/

- ↑ https://sciencing.com/chromosomes-duplicate-during-cell-life-cycle-3261.html?q2201904

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK9876/

- ↑ https://sciencing.com/g2-phase-what-happens-in-this-subphase-of-the-cell-cycle-13717821.html?q2201904

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK9876/

- ↑ https://sciencing.com/event-follow-dna-replication-cell-cycle-23039.html

- ↑ https://www.nature.com/scitable/definition/spindle-fibers-304/

- ↑ https://sciencing.com/stages-typical-cell-cycle-6160435.html

- ↑ https://sciencing.com/stages-typical-cell-cycle-6160435.html

- ↑ https://sciencing.com/stages-typical-cell-cycle-6160435.html

- ↑ https://sciencing.com/stages-typical-cell-cycle-6160435.html

- ↑ https://sciencing.com/event-follow-dna-replication-cell-cycle-23039.html

- ↑ https://www.nature.com/scitable/topicpage/cell-division-and-cancer-14046590/

- ↑ https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.94.7.2776

- ↑ https://sciencing.com/chromosomes-duplicate-during-cell-life-cycle-3261.html?q2201904

- ↑ https://sciencing.com/chromosomes-duplicate-during-cell-life-cycle-3261.html?q2201904

- ↑ https://sciencing.com/chromosomes-duplicate-during-cell-life-cycle-3261.html?q2201904

- ↑ https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.94.7.2776

- ↑ https://biologydictionary.net/prokaryotes-vs-eukaryotes/