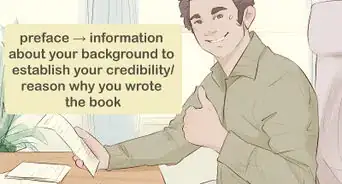

This article was co-authored by Dan Klein. Dan Klein is an improvisation expert and coach who teaches at the Stanford University Department of Theater and Performance Studies as well as at Stanford's Graduate School of Business. Dan has been teaching improvisation, creativity, and storytelling to students and organizations around the world for over 20 years. Dan received his BA from Stanford University in 1991.

There are 10 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

This article has been viewed 79,753 times.

Creative writing is a great way to let your imagination run wild and share your creativity with others. However, while it's easy to think up ideas for a good story, actually writing one is a different matter. A good drama is a combination of character and plot development, and most of the work comes in the brainstorming process. Once you've finished writing your first draft, your revisions are just as important as your brainstorming.

Steps

Developing Your Characters

-

1Research literary archetypes. Some stories have idiosyncratic characters that draw the reader’s attention by their originality — but when you're trying to write a dramatic story, you might benefit from working within the tradition of literary archetypes or stock characters. An archetype is a sort of template for a character that is recognizable, but onto which you can layer the details that make your character unique.[1] If readers don't have to learn a new type of character, they can immerse themselves immediately into your world, because they know how to read this "type" of literature. Archetypes allow the emotional tension to rise more quickly to the surface.

- Think of your favorite characters, and what universal character types they might stand in for. Why do these characters speak to you?

- The psychologist Carl Jung delineated personality archetypes on which he wrote extensively.[2] Literature is often interpreted through this approach, so it will be helpful to be familiar with Jungian archetypes.

- For example, the “Mother” archetype is positively characterized by sympathy, instinctual wisdom, and nurturing, but can be negatively characterized by secrecy and inescapability.

- The “Warrior” is a hero marked by courage and strength — someone who engages in head to head conflict and overcomes obstacles through strength of will.

- Byronic heroes, named after the English Romantic poet Lord Byron, tend to be darkly handsome and intelligent, but cynical and self-destructive. They are often loners, misunderstood and mistreated by society, like Pride and Prejudice’s Mr. Darcy.

-

2Flesh out your archetypes with unique details. The trick to working with archetypes is to start with a universal template then make it your own. If you simply deliver a pure archetype, your characters will seem too familiar to your readers, and they won’t care as much. When trying to write a dramatic story, it's important that your character have a uniquely moving nature in his/her own right.

- Was your character always like this? If not, what made him or her this way?

- In what contexts does your character act unexpectedly? For example, Jane Eyre's Edward Rochester was a harsh man who was for some reason still beloved by his staff. Despite his bad reputation, he also looked after a young French orphan for reasons unexplained until the author was ready to reveal more about the character.

- Blending characteristics from different archetypes can result in unexpected twists that ratchet up the reader's emotional investment in a dramatic story. For example, if your hero or heroine is normally a “Warrior” who usually overcomes obstacles on their own, the reader will be especially moved when he or she needs to be rescued by a character who is usually a damsel in distress.

Advertisement -

3Get to know your characters. For readers to get emotionally invested in your story, they have to engage in the “willing suspension of disbelief,” which is to say that you must convince them to feel for your made-up characters just as they would for real people in the world. Before you can convince your reader that your characters are real, you must get to know them so well that they become real to you.

- Think about who your main characters are before you even sit down to write the story.

- Flesh out their backstories. In fiction, readers meet the characters at a point in their lives of the author’s choosing, but there’s a whole life that has been led before the story began. Even if you don’t include those details in your story, think about them.

- Regardless of what point of view you write the actual story from, do writing exercises where you write from the first person point of view of all your main characters. Try to get into their mindsets. This will help your audience empathize and identify with your character.[3]

- Imagine what the darkest days of your main characters' lives were, and have them speak from that moment.

-

4Develop your character arc.[4] Flannery O’Connor said that the problem with many beginning writers is that “They want to write about problems, not people,” and that “a story always involves in a dramatic way, the mystery of personality.” She believed that readers connect more with the characters in a story than with the events that unfold, and that the real movement in a story is the revealing of a character’s true nature through the unfolding of plot.

- Flannery O’Connor’s “Good Country People” is a short story in which both main characters change greatly — Hulga Hopewell because she herself changes, and the Bible salesman because the reader's perception of him changes.[5]

- The reader doesn't even like Hulga at first because she is too proud and arrogant, and she treats people with condescension. However, the story ends with a moment of revelation in which she comes to the crushing realization of her vulnerability and silliness. Even though we didn't like her at first, the reader is moved to empathy.

- The Bible salesman does not actually evolve at all. Though the reader likes him at first because he is polite and kind, his later actions make him repulsive. In this case, his true nature doesn't change, but is masked and then revealed, causing a change in the reader's perception.

- The dramatic intensity of this story is due in large part to the complete reversal of the reader's attachments to characters: you go from disliking to feeling bad for Hulga, and you go from liking to despising the Bible salesman.

- A character arc that takes the reader by surprise will work well in a dramatic story.

Developing a Plot

-

1Map out the central conflicts of your story. Conflict is important in any story, even a comedy. Especially in a dramatic story, however, you must pay special attention to it. Nobody wants to read a drama where nothing’s at stake, because the emotional intensity would quickly flat-line.[6] There are three dimensions of conflict: external-world conflict, external-personal conflict, and internal conflict.[7] A comedy might make use of as few as one of these dimensions, but a dramatic story must make use of all three.

- External-world conflict is a problem external to the main character(s) — something beyond their control. It can be as grand in scale as a war, or as small and domestic as a character’s parents getting divorced.

- External-personal conflict is a conflict between your characters. Examples might be two characters fighting over a common romantic interest, or two politicians going head-to-head in a political campaign.

- Internal conflict is a character’s struggle to overcome their greatest personal weakness. For example, a character might have to overcome their fear of commitment to find happiness in a relationship, or overcome their arrogance to succeed in their career.

- Because the success of your dramatic story relies so heavily on the reader's engagement with your conflicts, it's important that you map out your conflicts during the brainstorming process, before you begin drafting.

-

2Decide your character or characters’ main goal or motivation. You may be tempted to describe your story in terms of “what it’s about,” but it will be more effective if you describe it to yourself in terms of “what your character wants.” This will keep you in your reader's mindset: in a drama, the reader wants your main character to find success and happiness. By concentrating on your character's goal or motivation, you will focus on ideas and details that will make your reader more invested in your story.

- Your story might have a very clear and explicit goal, such as “to leave behind an impoverished past by getting into an Ivy League college,” or your character’s motivation might be less defined — to cope after the death of a spouse, for example.

- Flesh out what’s at stake for the character if they fail to achieve that goal.

- Are the results disastrous and epic in scale for the public, or merely monotonous and quietly depressing for the individual character?

- Remember that in a big splashy adventure story, epic disaster might be sufficient for emotional stakes.

- However, in a drama, the story needs intimate, personal emotional stakes. The general public in the world of your story are not nearly as important as the one or two characters you're asking your reader to care for.

- Focus on the individual story, goals, and repercussions, not the larger story beyond your main character(s).

-

3Establish the costs and benefits for your characters.[8] You reader will get more involved with your story if they have a clear sense that your character is suffering in some way. What will your character have to sacrifice to achieve their goal? And what will they gain by achieving it? By having clear costs and benefits, you can more easily get your reader to understand what’s at stake in your story.

- The costs might be emotional (unhappiness), physical (your main character is a police officer who gets shot the day before retirement), or circumstantial (your character loses their job because they reported their boss for improper conduct).

- Don't let your character's suffering become boring for the reader. For example, if a character is simply sad because their mother died for an entire story, the reader might turn against them and say "well, do something to try to work through your grief."

- However, if the reader sees the character trying and failing to move on from their mother's death — doing their best, sacrificing, and still suffering in new ways that only freshen and sharpen their grief — then they will suffer along with your character instead of growing distant from them.

- For example, your character might feel frustrated that they don't connect with the therapist they started seeing; that the estranged father they reconnected with in the wake of their mother's death is a brash jerk, or even just quietly disappointing; that their attempt to go out on a date resulted in embarrassing failure; and so on.

- Each of those attempts to cope brings a new dimension to the character's emotional journey. The ultimate benefit of a happy ending will be magnified, and a sad ending rendered more devastating, by this accumulation of costs.

-

4Outline your plot points. You know your character arc, and you know your main character’s ultimate goal; now you have to plot out how the events in your story get them from point A to point B. Think of your story in terms of three acts: your setup and backstory; your conflict or confrontation; and your resolution.

- In Act 1, you explain who the characters are and reveal their goals. Provide the dramatic premise that will propel your plot, and the “inciting incident” that kicks your plot into gear.[9]

- In Act 2, throw obstacles in your main character’s way to prevent them from reaching their goal easily. It might seem at first as though your character will simply easily achieve their goal, before something takes their feet out from under them. After struggling against these obstacles, your character should reach a low point, where they cannot see a way to achieve their goal.

- In Act 3, your character reaches a turning point marked by the story’s climax. The conflicts you mapped out earlier reach their highest level of tension, bringing the reader to an emotional high point. After a final confrontation/climax, the storyline should resolve itself.

-

5Don’t feel pressured into a happy ending. Stories don’t have to resolve happily — they just have to resolve. The most important thing is that there be a sense of equilibrium. Unless you’re planning to write a sequel, the reader shouldn’t feel as though there is more to be told in this story. It’s perfectly fine to have a character motivated by a desire for happiness fail to find it with a romantic partner, but end up resigned to (even satisfied with) a quiet life alone, working on their hobbies.

- In Flannery O’Connor’s short story “The Life You Save Might Be Your Own,” the main female character is abandoned by her new husband, who only married her so he could steal her car. The story doesn’t end on a happy note, but we’ve learned everything we need to know about the husband to understand him as a human being. Although the ending is sad, we still feel satisfied in having read a complete, fleshed out depiction of a man’s nature.

-

6Fill out your first draft. Use all the outlines you’ve created about your character arcs and motivations, your costs and benefits, your plot points and acts, etc. to write your first draft. If, in the process of writing, you think the story would benefit from moving away from the ideas you outlined, feel free to take the story wherever you need it to go. All of your brainstorming work is a guideline, not a hard-and-true formula.

- Don’t worry about grammar and inventive language at this point. Your first draft is just about getting the bones of your story down: who are the characters, and what happens?

Revising Your Story

-

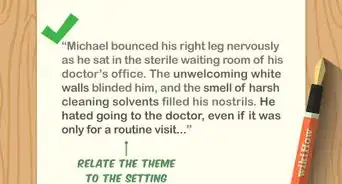

1Conduct research to make the world of your story more believable. If your story is about a doctor, learn the terminology a doctor would use in order to make the dialogue realistic. If your story is about a waitress, learn about the types of frustrations servers experience, like bad tippers, sore feet, etc. Work these details throughout your story to make the invented world come alive.

- It's the details of life that readers connect to most readily. It's difficult to imagine grand disasters — the death of a child if you've never experienced that, for example — but we can imagine the quiet indignities of life.

- For example, a character might not cry at a funeral, but dissolve into tears the next day because a customer blamed slow service on her as a waitress instead of realizing it was the kitchen holding up the order.

-

2Revise your dialogue. Dialogue is very difficult because it often comes across as stilted and unnatural. Find a partner and read all the dialogue in your story aloud, like you were performing the story as a play. Does it sound like normal human beings, or does it sound self-conscious and forced?

- If the dialogue feels forced, put what you’ve written away and try to imagine you are the character. Imagine what they need to communicate in that moment, then say it aloud in your own words, using your natural speech pattern.

- While your exposition should be grammatically correct, your dialogue will actually sound strange if it’s grammatically correct. Native speakers almost never speak “correctly” unless they’re delivering a speech or in an important situation like a job interview. Use elements such as contractions, sentence fragments, and interruptions to make your dialogue sound more realistic.

- Pay special attention to conversations at key dramatic moments, as they tend to get overwritten. When characters are voicing important thoughts, their language sometimes grows too grand and eloquent. Normal people don't change the way they speak when having important conversations — if anything, they sometimes become less coherent.

-

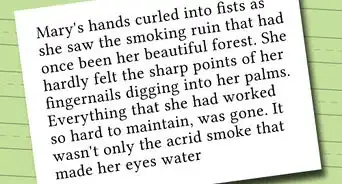

3Cut down your modifiers. The great Russian short story writer Anton Chekhov wrote often of the need for concision and compactness in good writing: “when you read proof cross out as many adjectives and adverbs as you can. You have so many modifiers that the reader has trouble understanding and gets worn out …The brain can't grasp all that at once, and art must be grasped at once, instantaneously.”

- Use strong verbs and nouns to pack a greater punch. Note the improvement from “she sat around lazily” to “she lazed.”

- Sometimes, you will need to keep adjectives and adverbs to make your writing sound natural, so don’t go overboard with cutting them out. If you find that you're relying on the adjective or adverb to do the work for you --- for example, using "She said, happily" as a dialogue tag, instead of demonstrating the character's emotion through what she says and how she acts --- definitely eliminate those.

-

4Revise for restraint. Sometimes, we get so carried away with the drama of what we’re writing that we blow it out of proportion. A little restraint goes a long way. Mark Twain once said to “Substitute "damn" every time you're inclined to write "very"; your editor will delete it and the writing will be just as it should be.” It’s a good lesson to keep in mind so your reader doesn't roll their eyes at how hard your story is trying to manipulate the emotional tension. Let the story work subtly on the reader instead of trying to boss them around into feeling what you want them to feel.

- Maintain a balance between the acts of your plot. The emotional tension of your language shouldn’t be turned all the way up throughout your entire story; it should be highest during the climax.

-

5Revise for pacing. Does your climax play out and resolve itself too quickly or easily? If so, add to the climactic scene so that the resolution feels more hard-earned and satisfying. If your first act, where you’re setting up your characters and context, seems to drag on for too long, cut it down to size! As Elmore Leonard said, “Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip.”[10]

-

6Don’t be afraid to cut. The best writers know that they have to be cold to their work. It’s hard to throw away even just a word or a line, much less an entire scene, but you have to be willing to sacrifice that work to better serve the overall story. As Truman Capote said, “I’m all for the scissors. I believe more in the scissors than I do in the pencil.”[11]

-

7Do multiple rounds of revision. Good stories take time, so don’t think that you’re going to get it all done in one sitting. The trick to good revising is learning to distance yourself from your work. When you first write something, you might immediately be in love with it — and that’s fine! You should be proud of what you’ve accomplished. But after a few days have passed, you’ll be able to see the flaws a little more clearly.

- Give yourself a few days between rounds of revision so that you can see the story objectively.

- Save all your drafts, so you can undo changes you’ve made if you decide they don’t work.

Expert Q&A

-

QuestionWhat are some of the essential elements of a story?

Dan KleinDan Klein is an improvisation expert and coach who teaches at the Stanford University Department of Theater and Performance Studies as well as at Stanford's Graduate School of Business. Dan has been teaching improvisation, creativity, and storytelling to students and organizations around the world for over 20 years. Dan received his BA from Stanford University in 1991.

Dan KleinDan Klein is an improvisation expert and coach who teaches at the Stanford University Department of Theater and Performance Studies as well as at Stanford's Graduate School of Business. Dan has been teaching improvisation, creativity, and storytelling to students and organizations around the world for over 20 years. Dan received his BA from Stanford University in 1991.

Improvisation Coach You should always include a character that the audience cares about. The reader needs someone to identify and empathize with. Also, make sure that something in the story changes the relationships between your characters so that you can stimulate conflict and give your audience something to focus on.

You should always include a character that the audience cares about. The reader needs someone to identify and empathize with. Also, make sure that something in the story changes the relationships between your characters so that you can stimulate conflict and give your audience something to focus on. -

QuestionIf I want to write an adventure story how would the language or pattern be?

Community AnswerResearch what to do by reading adventure books. A website I would recommend is Wattpad, as it has many user-created stories, as well as a comment section and a PM (private message) system that you could use to ask Wattpad authors for advice.

Community AnswerResearch what to do by reading adventure books. A website I would recommend is Wattpad, as it has many user-created stories, as well as a comment section and a PM (private message) system that you could use to ask Wattpad authors for advice.

References

- ↑ http://education-portal.com/academy/lesson/archetype-in-literature-definition-examples-quiz.html#lesson

- ↑ The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, by Carl Jung

- ↑ Dan Klein. Storytelling Teacher. Expert Interview. 22 March 2019.

- ↑ http://narrativefirst.com/vault/what-character-arc-really-means

- ↑ http://faculty.weber.edu/Jyoung/English%206710/Good%20Country%20People.pdf

- ↑ Dan Klein. Storytelling Teacher. Expert Interview. 22 March 2019.

- ↑ http://thewritepractice.com/3d-conflict/

- ↑ http://www.how-to-write-a-book-now.com/plot-outline.html

- ↑ http://narrativefirst.com/articles/plot-points-and-the-inciting-incident

- ↑ http://www.theguardian.com/books/2010/feb/24/elmore-leonard-rules-for-writers

- ↑ Conversations With Capote, by Lawrence Grobel

About This Article

To write a dramatic story, start by mapping out the central conflicts of your story, including conflicts that are out of your main character's control, like a war or death of a friend. Additionally, a dramatic story will have external-personal conflicts, like a fight with a friend or a hotly contested political campaign. Then, the internal conflict shows the character's struggle to overcome a personal weakness, like lying or cheating. Also, come up with a goal for your character that drives the decisions, like moving back home or becoming a word renowned chef. To learn how to develop your characters in your dramatic story, keep reading!