العلاقات العربية الصينية

العلاقات العربية الصينية، تعود تاريخياً إلى عهد الخلافة الراشدة، مع وجود طرق تجارية مهمة وعلاقات دبلوماسية جيدة. منذ تأسيس جمهورية الصين الشعبية، تقاربت العلاقات العربية الصينية الحديثة بشكل كبير، حيث ساعد منتدى التعاون الصيني العربي الجانبين على إقامة شراكة جديدة في عصر العولمة المتنامية. ونتيجة لذلك، تم الحفاظ على علاقات اقتصادية وسياسية وعسكرية وثيقة بين الجانبين.[1] [2] منذ عام 2018، أصبحت العلاقات أكثر دفئًا بشكل ملحوظ، مع تبادل جمهورية الصين الشعبية والدول العربية زيارات دولة وإنشاء آلية تعاون وتقديم الدعم لبعضهما البعض.[3] [4] [5]

| العلاقات العربية الصينية | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|||

| |||

| العلاقات العربية الصينية | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|||

| |||

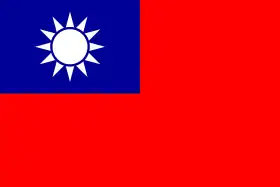

منذ عام 1990، لم يكن لأي دولة عربية علاقات دبلوماسية رسمية مع جمهورية الصين (تايوان)، على الرغم من تمثيلها دبلوماسيًا في بعض الدول عبر مكتب الممثل الاقتصادي والثقافي في تايبيه.

التاريخ

عصر القرون الوسطى

خلال عهد أسرة تانغ، عندما أقيمت العلاقات مع العرب لأول مرة، أطلق الصينيون على العرب اسم «داي» (大 食).[6] [7] [8] [9] كانت الخلافة تسمى «دا يي جو» (大 食 國).[10] ويُعتقد أن الكلمة نسخ من اللفظ الفارسي «تازك» أو «تازي»، المشتق بدوره من اسم قبيلة طيء العربية.[11] المصطلح الحديث للعرب هو «الأبو» (阿拉伯).

أرسل الخليفة عثمان بن عفان سفارة إلى بلاط تانغ في تشانغآن.[12] وتذكر المصادر العربية أن قتيبة بن مسلم استولى لفترة وجيزة على كاشغر وانسحب بعد اتفاق مع ملك الصين.[13]

خلعت الخلافة الأموية عام 715م، إخشيد، ملك وادي فرغانة، ونصبت ملكًا جديدًا ألوتار على العرش. هرب الملك المخلوع إلى كوتشا، وسعى للتدخل الصيني. حيث أرسل الصينيون 10000 جندي تحت قيادة تشانغ شياو سونغ إلى فرغانة.

قاد الجنرال الصيني تانغ جياهوي الصينيين لهزيمة الهجوم العربي التبتي التالي في وقعة أقسو.[14] وانضم إلى الهجوم على أقسو تورجش خان سلوك.[15] [16] تعرضت كل من أوش تورفان وأقسو لهجوم من قبل قوات تورجش والعرب والتبت في 15 أغسطس 717.[17] [18]

على الرغم من أن أسرة تانغ والخلافة العباسية قد تقاتلتا في معركة نهر طلاس، في 11 يونيو 758، وصلت سفارة عباسية إلى تشانغآن بالتزامن مع مبعوثي خاقانية الأويغور.[19]

دو هوان وهو صيني تم أسره في طلاس، تم إحضاره إلى بغداد وقام بجولة في جميع أنحاء الخلافة. ولاحظ أنه في مرو وخراسان، عاش العرب والفرس في تجمعات مختلطة.[20] قدم رويته للعرب في تونغديان في عام 801 والتي كتبها عندما عاد إلى الصين.

كانت شبه الجزيرة العربية [داشي] في الأصل جزءًا من بلاد فارس. الرجال لديهم أنوف عالية، داكنون وملتحون. النساء جميلات جدا [بيض] وعندما يخرجن يغطين وجوههن. يعبدون الله خمس مرات يوميًا. يرتدون أحزمة فضية مع سكاكين فضية معلقة. لا يشربون الخمر ولا يستخدمون الموسيقى. يستوعب مكان عبادتهم مئات الأشخاص. كل سبعة أيام يجلس الملك (الخليفة) في الأعلى، ويتحدث لمن هم في الأسفل قائلاً: «أولئك الذين قتلهم العدو يولدون في السماء. أولئك الذين يقتلون العدو ينالون السعادة». لذلك هم عادة مقاتلون شجعان. أرضهم رملية وحجرية غير صالحة للزراعة؛ لذلك يصطادون ويأكلون اللحم.

هذه (الكوفة) مكان عاصمتهم. رجالها ونسائها جذابون في المظهر وكبيرون في المكانة. ملابسهم جميلة، وسلوكهم متمهل وجميل. عندما تخرج النساء، فإنهن يغطين وجوههن دائمًا، بغض النظر عن مكانتهن. يصلون إلى الجنة خمس مرات في اليوم.

أتباع طائفة «الداشي» (العرب) لديهم وسيلة للدلالة على درجات العلاقات الأسرية، لكنها متدهورة ولا يهتمون بها. إنهم لا يأكلون لحوم الخنازير والكلاب والحمير والخيول، ولا يحترمون ملك البلاد ولا والديهم ولا يؤمنون بالقوى الخارقة للطبيعة ولا يضحون إلا للجنة ولا لأحد آخر. وفقًا لعاداتهم، فإن كل يوم سابع هو يوم عطلة، لا يتم فيه أي تجارة ولا معاملات نقدية. عندما يشربون الكحول، فإنهم يتصرفون بطريقة سخيفة وغير منضبطة طوال اليوم.

قدم مبعوث عربي خيولاً وحزاماً للصينيين عام 713م، لكنه رفض الانحناء للإمبراطور، قائلاً: «في بلادي لا نركع إلا لله وليس لأمير». رغب البلاط بقتل المبعوث، لكن أحد الوزراء تدخل قائلاً: «لا ينبغي اعتبار الاختلاف في آداب البلاط للدول الأجنبية جريمة».[27]

أقام الخليفة هارون الرشيد تحالفًا مع الصين.[28] وتم تسجيل العديد من السفارات من الخلفاء العباسيين إلى البلاط الصيني في حوليات تانغ، وأهمها سفارات أبو العباس السفاح وأبو جعفر المنصور وهارون الرشيد. يُعرف العباسيون، في التاريخ الصيني باسم «هيه إي تا شيه» أيّ «العرب ذوو الرداء الأسود».[29] [30] [31] [32] [33] [34] [35] [36] [37] [38] [39] [40]

ووفقا للأستاذ سامي سويد، قام المبشرون الفاطميون بالدعوة في الصين في عهد العزيز بالله الفاطمي.[41]

التجارة

كان المسلمون من شبه الجزيرة العربية على علاقات تجارية وطيدة مع الصين.[42] على سبيل المثال، استوردت الصين اللبان من جنوب الجزيرة العربية عبر سريفيجايا.[43] وتم تداول المنتجات عن طريق الطرق البحرية بين الصين والعرب.[44]

القرن العشرين

أقامت جمهورية الصين تحت حكم الكومينتانغ علاقات مع مصر والمملكة العربية السعودية في الثلاثينيات. رعت الحكومة الصينية طلابًا مثل وانغ جينغزاي ومحمد ماكين للذهاب إلى جامعة الأزهر للدراسة. كما قام الحجاج المسلمون بالحج إلى مكة من الصين.[45]

تم إرسال المسلمين الصينيين إلى المملكة العربية السعودية ومصر للتنديد باليابانيين خلال الحرب الصينية اليابانية الثانية. [45]

في عام 1939، تم إرسال عيسى يوسف ألبتكين وما فوليانغ من قبل الكومينتانغ إلى دول الشرق الأوسط مثل مصر وتركيا وسوريا لكسب الدعم للصين في الحرب مع اليابان.[46] بالإضافة إلى وانج تسنغشان وشوي وينبو ولين تشونغ مينغ.[47]

حافظت مصر على العلاقات حتى عام 1956، عندما قطع جمال عبد الناصر العلاقات وأقامها مع جمهورية الصين الشعبية بدلاً من ذلك. ثم أُمر ما بوفانج، الذي كان يعيش في مصر آنذاك، بالانتقال إلى المملكة العربية السعودية، وأصبح سفير جمهورية الصين في المملكة العربية السعودية.

بحلول التسعينيات، قطعت جميع الدول العربية العلاقات مع جمهورية الصين وأقامت علاقات مع جمهورية الصين الشعبية.

بدأت العلاقات بين الصين وجامعة الدول العربية كمنظمة رسميًا في عام 1956، وفي عام 1993 افتتحت الجامعة العربية مكتبها الأول في الصين، عندما ذهب الأمين العام آنذاك أحمد عصمت عبد المجيد في زيارة رسمية إلى بكين.[48] في عام 1996، أجرى الرئيس الصيني جيانغ زيمين مقابلة مع عبد المجيد خلال زيارته لمصر، وأصبح أول زعيم صيني يزور جامعة الدول العربية رسميًا. [48]

القرن الحادي والعشرين

كتب آدم هوفمان وروي يلينك من معهد الشرق الأوسط في مايو 2020 أن تفشي جائحة فيروس كورونا، الذي انتشر من الصين إلى الدول العربية، قد وضع ديناميكية معقدة في العلاقات بين الجانبين، وخلق فرصة للتضامن والمساعدة، وفي نفس الوقت تفاقم التحديات الحالية.[49]

أيدت 15 دولة من أصل 22 دولة عضو في جامعة الدول العربية قانون الأمن الوطني لهونغ كونغ لعام 2020 في الأمم المتحدة، إلى جانب 38 دولة أخرى.[50] [51]

يوجد 14 معهد كونفوشيوس في العالم العربي. تعد معاهد كونفوشيوس إحدى الطرق الرئيسية التي تستثمر بها الصين القوة الناعمة في الدول العربية وفي العالم. بعد 14 عامًا من العمل في المنطقة، يمكن القول إن المعاهد، كأداة للقوة الناعمة الصينية، قد اخترقت العالم العربي بشكل فعال وهي موضع ترحيب دون انتقادات كبيرة.[52]

منتدى التعاون الصيني العربي

تأسس منتدى التعاون العربي الصيني بشكل رسمي خلال زيارة الرئيس هو جينتاو لمقر الجامعة في يناير 2004. وأشار هو في ذلك الوقت إلى أن تشكيل المنتدى كان استمرارا للصداقة التقليدية بين الصين والعالم العربي وخطوة مهمة لتعزيز العلاقات الثنائية في ظل الظروف الجديدة.

وصرح لى ان «اقامة المنتدى سوف يساعد على توسيع التعاون متبادل المنفعة في مجموعة متنوعة من المجالات».

«قدمت الصين أربعة مقترحات. أولا، الحفاظ على الاحترام المتبادل والمعاملة العادلة والتعاون المخلص على الجبهة السياسية. ثانياً، تعزيز العلاقات الاقتصادية والتجارية من خلال التعاون في الاستثمار والتجارة والمشاريع المتعاقد عليها وخدمة العمل والطاقة والنقل والاتصالات والزراعة وحماية البيئة والمعلومات. ثالثا، توسيع التبادلات الثقافية. واخيرا تدريب الافراد». اتفق وزراء الخارجية العرب الذين حضروا الاجتماع على أن الافتتاح الرسمي للمنتدى كان حدثًا مهمًا في تاريخ العلاقات العربية مع الصين. وقدموا مجموعة متنوعة من المقترحات حول تعزيز الصداقة والتعاون الصيني العربي. وفي ختام الاجتماع وقع لي والأمين العام لجامعة الدول العربية عمرو موسى إعلانا وخطة عمل للمنتدى. وصل لي إلى القاهرة مساء الأحد في زيارة لمصر تستغرق ثلاثة أيام، وهي المحطة الأخيرة في جولة في الشرق الأوسط شملت السعودية واليمن وسلطنة عمان.

انعقدت الدورة الثانية من منتدى التعاون الأمني بين الفلسطينيين والإسرائيليين في بكين عام 2006، وناقشت الاقتراح الصيني لجعل الشرق الأوسط منطقة خالية من الأسلحة النووية، وناقشت عملية السلام بين الفلسطينيين والإسرائيليين. في حين من المقرر أن يعقد منتدى التعاون الثالث في البحرين 2008.

مقارنة

| الاسم | جامعة الدول العربية | جمهورية الصين الشعبية [53] | تايوان [54] |

|---|---|---|---|

| العلم |  |

|

|

| تعداد السكان | 407,251,880 (2018) | 1,403,500,365 (2017) | 23,577,271 (2018) |

| المساحة | 13,953,041 كم 2 (5,382,910 ميل مربع) | 9,640,821 كم 2 (3,704,427 ميل مربع) | 36,193 كم 2 (13,974 ميل مربع) [55] |

| الكثافة السكانية | 24.33 / كم 2 (63 / ميل مربع) | 139.6 / كم 2 (363.3 / ميل مربع) | 644 / كم 2 (1,664 / ميل مربع) |

| العاصمة | القاهرة | بكين | تايبيه (بحكم الواقع) نانجينغ (بحكم القانون) |

| أكبر مدينة | القاهرة - 19,500,000 (20,439,541 المنطقة الحضرية) | شنغهاي - 19,210,000 | تايبيه الجديدة - 3,935,072 |

| نوع المنظمة والحكومة | منظمة إقليمية واتحاد سياسي | دولة مركزية | دولة مركزيةجمهورية دستورية شبه رئاسية |

| اللغات الرسمية | العربية | الماندرين (بوتونغهوا) | الماندرين (جويو) |

| الأديان الرئيسية | 91% الإسلام | ديانة شعبية صينية والبوذية والطاوية على حد سواء | 35.1% بوذية

33.0% طاوية 18.7% إلحاد 3.9% مسيحية 3.5% لكوان تاو 7.3% أخرى |

| الناتج المحلي الإجمالي (الاسمي) | 3.5 تريليون دولار (15,915 دولار للفرد) | 13.118 ترليون دولار (9,376 دولار للفرد) | 566.757 مليار دولار (24,027 دولار للفرد) |

البيان المشترك

أحد المشاريع المشتركة الرئيسية يشمل البيئة، وقعت الجامعة العربية والصين على البرنامج التنفيذي للبيان المشترك للتعاون البيئي للفترة 2008-2009

وقعت جامعة الدول العربية وحكومة جمهورية الصين الشعبية على البيان المشترك بشأن التعاون البيئي (المشار إليه باسم البيان المشترك) في 1 يونيو 2006. يعتبر البيان المشترك أداة مهمة تهدف إلى تعميق الشراكة البيئية الإقليمية بين الطرفين. منذ توقيع البيان المشترك، نظمت وزارتا التجارة وحماية البيئة الصينيتان دورتين تدريبيتين لحماية البيئة في يونيو 2006 ويونيو 2007 على التوالي، في الصين.

من أجل تنفيذ المادة 4 من البيان المشترك، على كلا الطرفين تطوير هذا البرنامج التنفيذي لعامي 2008 و2009. ويهدف إلى تعزيز التعاون بين جامعة الدول العربية والصين في مجال حماية البيئة، بما يتماشى مع التطلعات المشتركة للطرفين ومصالحهما طويلة المدى.

وقع هذه المعاهدة السفير أحمد بن حلي بموافقة الأمين العام، وشو تشينغهوا مدير الإدارة العامة للتعاون الدولي بوزارة حماية البيئة.[56]

انظر أيضًا

مراجع

- "Commentary: Sino-Arab relations to enjoy bright future in new era - People's Daily Online"، en.people.cn، مؤرشف من الأصل في 6 أغسطس 2019.

- "Special show of affection reserved for new era of Chinese relations"، The National (باللغة الإنجليزية)، مؤرشف من الأصل في 5 أكتوبر 2020.

- "China Focus: China, Arab states to forge strategic partnership - Xinhua | English.news.cn"، www.xinhuanet.com، مؤرشف من الأصل في 30 نوفمبر 2021.

- "China offers $105m to Arab countries, political support to Palestine"، Middle East Eye (باللغة الإنجليزية)، مؤرشف من الأصل في 6 أكتوبر 2018.

- "China, Arab states agree to enhance cooperation under new strategic partnership"، Arab News (باللغة الإنجليزية)، 10 يوليو 2018، مؤرشف من الأصل في 30 نوفمبر 2021.

- Edward Allworth (1994)، Central Asia, 130 Years of Russian Dominance: A Historical Overview، Duke University Press، ص. 624–، ISBN 0-8223-1521-1، مؤرشف من الأصل في 24 يونيو 2016.

- Theobald, Ulrich، "Dasi 大食 (www.chinaknowledge.de)"، www.chinaknowledge.de، مؤرشف من الأصل في 12 يونيو 2018، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 18 أبريل 2018.

- Yingsheng, Liu (01 يوليو 2001)، "A century of Chinese research on Islamic Central Asian history in retrospect"، Cahiers d'Asie centrale (9): 115–129، مؤرشف من الأصل في 13 مايو 2013، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 18 أبريل 2018.

- Graham Thurgood (يناير 1999)، From Ancient Cham to Modern Dialects: Two Thousand Years of Language Contact and Change، University of Hawaii Press، ص. 228–، ISBN 978-0-8248-2131-9، مؤرشف من الأصل في 5 يوليو 2021.

- E. Bretschneider (1871)، On the knowledge possessed by the ancient Chinese of the Arabs and Arabian colonies: and other western countries, mentioned in Chinese books، LONDON 60 PATERNOSTER ROW.: Trübner & co.، ص. 6، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 28 يونيو 2010.

{{استشهاد بكتاب}}: صيانة CS1: location (link)(Original from Harvard University) - Hyunhee Park (27 أغسطس 2012)، Mapping the Chinese and Islamic Worlds: Cross-Cultural Exchange in Pre-Modern Asia، Cambridge University Press، ص. 203–، ISBN 978-1-139-53662-2، مؤرشف من الأصل في 26 يناير 2020.

- Twitchett, Denis (2000)، "Tibet in Tang's Grand Strategy"، في van de Ven (المحرر)، Warfare in Chinese History، Leiden: Koninklijke Brill، ص. 106–179 [125]، ISBN 90-04-11774-1

- Muhamad S. Olimat (27 أغسطس 2015)، China and Central Asia in the Post-Soviet Era: A Bilateral Approach، Lexington Books، ص. 10–، ISBN 978-1-4985-1805-5، مؤرشف من الأصل في 28 يناير 2022.

- Insight Guides (01 أبريل 2017)، Insight Guides Silk Road، APA، ISBN 978-1-78671-699-6، مؤرشف من الأصل في 10 أكتوبر 2021.

- René Grousset (1970)، The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia، Rutgers University Press، ص. 114–، ISBN 978-0-8135-1304-1، مؤرشف من الأصل في 16 أكتوبر 2021،

aksu 717.

- Jonathan Karam Skaff (06 أغسطس 2012)، Sui-Tang China and Its Turko-Mongol Neighbors: Culture, Power, and Connections, 580-800، Oxford University Press، ص. 311–، ISBN 978-0-19-999627-8، مؤرشف من الأصل في 29 يناير 2022.

- Christopher I. Beckwith (28 مارس 1993)، The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia: A History of the Struggle for Great Power Among Tibetans, Turks, Arabs, and Chinese During the Early Middle Ages، Princeton University Press، ص. 88–89، ISBN 0-691-02469-3، مؤرشف من الأصل في 18 ديسمبر 2021.

- Marvin C. Whiting (2002)، Imperial Chinese Military History: 8000 BC-1912 AD، iUniverse، ص. 277–، ISBN 978-0-595-22134-9، مؤرشف من الأصل في 30 سبتمبر 2021.

- Schafer, Edward H. (1985) [1963]، The Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A study of T'ang Exotics (ط. 1st paperback)، Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press، ص. 26، ISBN 0-520-05462-8

- Harvard University. Center for Middle Eastern Studies (1999)، Harvard Middle Eastern and Islamic review, Volumes 5-7، Center for Middle Eastern Studies, Harvard University، ص. 89، مؤرشف من الأصل في 5 يناير 2022، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 28 نوفمبر 2010.

- E. Bretschneider (1871)، On the knowledge possessed by the ancient Chinese of the Arabs and Arabian colonies: and other western countries, mentioned in Chinese books، LONDON: Trübner & co.، ص. 7، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 28 يونيو 2010،

rise again in heaven be happy.

(Original from Harvard University) - Donald Leslie (1998)، The integration of religious minorities in China: the case of Chinese Muslims، Australian National University، ص. 10، ISBN 0-7315-2301-6، مؤرشف من الأصل في 1 فبراير 2022، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 28 نوفمبر 2010.

- Hartford Seminary Foundation (1929)، The Moslem world, Volume 19، Published for the Nile Mission Press by the Christian Literature Society for India، ص. 258، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 28 نوفمبر 2010.(Original from the University of California)

- Donald Daniel Leslie (1998)، "The Integration of Religious Minorities in China: The Case of Chinese Muslims" (PDF)، The Fifty-ninth George Ernest Morrison Lecture in Ethnology، ص. 5، مؤرشف من الأصل (PDF) في 17 ديسمبر 2010، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 30 نوفمبر 2010.

- Harvard University. Center for Middle Eastern Studies (1999)، Harvard Middle Eastern and Islamic review, Volumes 5-7، Center for Middle Eastern Studies, Harvard University، ص. 92، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 28 نوفمبر 2010.

- Wolbert Smidt (2001)، "A Chinese in the Nubian and Abyssinian Kingdoms (8th Century)"، Chroniques Yéménites (9)، doi:10.4000/cy.33، مؤرشف من الأصل في 2 ديسمبر 2017، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 14 ديسمبر 2010.

- E. Bretschneider (1871)، On the knowledge possessed by the ancient Chinese of the Arabs and Arabian colonies: and other western countries, mentioned in Chinese books، LONDON: Trübner & co.، ص. 8، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 28 يونيو 2010،

713 envoy appeared from ta shi.

(Original from Harvard University) - Dennis Bloodworth؛ Ching Ping Bloodworth (2004)، The Chinese Machiavelli: 3000 years of Chinese statecraft، Transaction Publishers، ص. 214، ISBN 0-7658-0568-5، مؤرشف من الأصل في 28 سبتمبر 2021، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 28 يونيو 2010.

- Marshall Broomhall (1910)، Islam in China: a neglected problem، LONDON 12 PATERNOSTER BUILDINGS, E.C.: Morgan & Scott, ltd.، ص. 25, 26، مؤرشف من الأصل في 28 سبتمبر 2021، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 14 ديسمبر 2011،

CHAPTER II CHINA AND THE ARABS From the Rise of the Abbaside Caliphate With the rise of the Abbasides we enter upon a somewhat different phase of Moslem history, and approach the period when an important body of Moslem troops entered and settled within the Chinese Empire. While the Abbasides inaugurated that era of literature and science associated with the Court at Bagdad, the hitherto predominant Arab element began to give way to the Turks, who soon became the bodyguard of the Caliphs, " until in the end the Caliphs became the helpless tools of their rude protectors." Several embassies from the Abbaside Caliphs to the Chinese Court are recorded in the T'ang Annals, the most important of these being those of (A-bo-lo-ba) Abul Abbas, the founder of the new dynasty, that of (A-p'u-cKa-fo) Abu Giafar, the builder of Bagdad, of whom more must be said immediately; and that of (A-lun) Harun al Raschid, best known, perhaps, in modern days through the popular work, Arabian Nights.1 The Abbasids or " Black Flags," as they were commonly called, are known in Chinese history as the Heh-i Ta-shih, " The Black-robed Arabs." Five years after the rise of the Abbasides, at a time when Abu Giafar, the second Caliph, was busy plotting the assassination of his great and able rival Abu Muslim, who is regarded as " the leading figure of the age " and the de facto founder of the house of Abbas so far as military prowess is concerned, a terrible rebellion broke out in China. This was in 755 A.d., and the leader was a Turk or Tartar named An Lu-shan. This man, who had gained great favour with the Emperor Hsuan Tsung, and had been placed at the head of a vast army operating against the Turks and Tartars on the north-west frontier, ended in proclaiming his independence and declaring war upon his now aged Imperial patron. The Emperor, driven from his capital, abdicated in favour of his son, Su Tsung (756-763 A.D.), who at once appealed to the Arabs for help. The Caliph Abu Giafar, whose army, we are told by Sir William Muir, " was fitted throughout with improved weapons and armour," responded to this request, and sent a contingent of some 4000 men, who enabled the Emperor, in 757 A.d., to recover his two capitals, Sianfu and Honanfu. These Arab troops, who probably came from some garrison on the frontiers of Turkestan, never returned to their former camp, but remained in China, where they married Chinese wives, and thus became, according to common report, the real nucleus of the naturalised Chinese Mohammedans of to-day. ^ While this story has the support of the official history of the T'ang dynasty, there is, unfortunately, no authorised statement as to how many troops the Caliph really sent.1 The statement, however, is also supported by the Chinese Mohammedan inscriptions and literature. Though the settlement of this large body of Arabs in China may be accepted as probably the largest and most definite event recorded concerning the advent of Islam, it is necessary at the same time not to overlook the facts already stated in the previous chapter, which prove that large numbers of foreigners had entered China prior to this date.

{{استشهاد بكتاب}}: صيانة CS1: location (link) - Frank Brinkley (1902)، China: its history, arts and literature, Volume 2، BOSTON AND TOKYO: J.B.Millet company، ج. 9-12 of Trübner's oriental series، ص. 149, 150, 151, 152، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 14 ديسمبر 2011،

It would seem, however, that trade occupied the attention of the early Mohammedan settlers rather than religious propagan dism; that while they observed the tenets and practised the rites of their faith in China, they did not undertake any strenuous campaign against either Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism, or the State creed, and that they constituted a floating rather than a fixed element of the population, coming and going between China and the West by the oversea or the overland routes. According to Giles, the true stock of the present Chinese Mohammedans was a small army of four thousand Arabian soldiers, who, being sent by the Khaleef Abu Giafar in 755 to aid in putting down a rebellion, were subsequently permitted to * * settle in China, where they married native wives. The numbers of this colony received large accessions in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries during the conquests of Genghis, and ultimately the Mohammedans formed an appreciable element of the population, having their own mosques and schools, and observing the rites of their religion, but winning few converts except among the aboriginal tribes, as the Lolos and the Mantsu. Their failure as propagandists is doubtless due to two causes, first, that, according to the inflexible rule of their creed, the Koran might not be translated into Chinese or any other foreign language; secondly and chiefly, that their denunciations of idolatry were as unpalatable to ancestor-worshipping Chinese as were their interdicts against pork and wine. They were never prevented, however, from practising their faith so long as they obeyed the laws of the land, and the numerous mosques that exist throughout China prove what a large measure of liberty these professors of a strange creed enjoyed. One feature of the mosques is noticeable, however: though distinguished by large arches and by Arabic inscriptions, they are generally constructed and arranged so as to bear some resemblance to Buddhist temples, and they have tablets carrying the customary ascription of reverence to the Emperor of China, — facts suggesting that their builders were not entirely free from a sense of the inexpediency of differentiating the evidences of their religion too conspicuously from those of the popular creed. It has been calculated that in the regions north of the Yangtse the followers of Islam aggregate as many as ten millions, and that eighty thousand are to be found in one of the towns of Szchuan. On the other hand, just as it has been shown above that although the Central Government did not in any way interdict or obstruct the tradal operations of foreigners in early times, the local officials sometimes subjected them to extortion and maltreatment of a grievous and even unendurable nature, so it appears that while as a matter of State policy, full tolerance was extended to the Mohammedan creed, its disciples frequently found themselves the victims of such unjust discrimination at the hand of local officialdom that they were driven to seek redress in rebellion. That, however, did not occur until the nineteenth century. There is no evidence that, prior to the time of the Great Manchu Emperor Chienlung (1736-1796), Mohammedanism presented any deterrent aspect to the Chinese. That renowned ruler, whose conquests carried his banners to the Pamirs and the Himalayas, did indeed conceive a strong dread of the potentialities of Islamic fanaticism reinforced by disaffection on the part of the aboriginal tribes among whom the faith had many adherents. He is said to have entertained at one time the terrible project of eliminating this source of danger in Shensi and Kansuh by killing every Mussulman found there, but whether he really contemplated an act so foreign to the general character of his procedure is doubtful. The broad fact is that the Central Government of China has never persecuted Mohammedans or discriminated against them. They are allowed to present themselves at the examinations for civil or military appointments, and the successful candidates obtain office as readily as their Chinese competitors.

Original from the University of California - Frank Brinkley (1904)، Japan [and China]: China; its history, arts and literature، LONDON 34 HENRIETTA STREET, W. C. AND EDINBURGH: Jack، ج. 10 of Japan [and China]: Its History, Arts and Literature، ص. 149, 150, 151, 152، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 14 ديسمبر 2011،

It would seem, however, that trade occupied the attention of the early Mohammedan settlers rather than religious propagan dism; that while they observed the tenets and practised the rites of their faith in China, they did not undertake any strenuous campaign against either Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism, or the State creed, and that they constituted a floating rather than a fixed element of the population, coming and going between China and the West by the oversea or the overland routes. According to Giles, the true stock of the present Chinese Mohammedans was a small army of four thousand Arabian soldiers, who, being sent by the Khaleef Abu Giafar in 755 to aid in putting down a rebellion, were subsequently permitted to * * settle in China, where they married native wives. The numbers of this colony received large accessions in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries during the conquests of Genghis, and ultimately the Mohammedans formed an appreciable element of the population, having their own mosques and schools, and observing the rites of their religion, but winning few converts except among the aboriginal tribes, as the Lolos and the Mantsu. Their failure as propagandists is doubtless due to two causes, first, that, according to the inflexible rule of their creed, the Koran might not be translated into Chinese or any other foreign language; secondly and chiefly, that their denunciations of idolatry were as unpalatable to ancestor-worshipping Chinese as were their interdicts against pork and wine. They were never prevented, however, from practising their faith so long as they obeyed the laws of the land, and the numerous mosques that exist throughout China prove what a large measure of liberty these professors of a strange creed enjoyed. One feature of the mosques is noticeable, however: though distinguished by large arches and by Arabic inscriptions, they are generally constructed and arranged so as to bear some resemblance to Buddhist temples, and they have tablets carrying the customary ascription of reverence to the Emperor of China, — facts suggesting that their builders were not entirely free from a sense of the inexpediency of differentiating the evidences of their religion too conspicuously from those of the popular creed. It has been calculated that in the regions north of the Yangtse the followers of Islam aggregate as many as ten millions, and that eighty thousand are to be found in one of the towns of Szchuan. On the other hand, just as it has been shown above that although the Central Government did not in any way interdict or obstruct the tradal operations of foreigners in early times, the local officials sometimes subjected them to extortion and maltreatment of a grievous and even unendurable nature, so it appears that while as a matter of State policy, full tolerance was extended to the Mohammedan creed, its disciples frequently found themselves the victims of such unjust discrimination at the hand of local officialdom that they were driven to seek redress in rebellion. That, however, did not occur until the nineteenth century. There is no evidence that, prior to the time of the Great Manchu Emperor Chienlung (1736-1796), Mohammedanism presented any deterrent aspect to the Chinese. That renowned ruler, whose conquests carried his banners to the Pamirs and the Himalayas, did indeed conceive a strong dread of the potentialities of Islamic fanaticism reinforced by disaffection on the part of the aboriginal tribes among whom the faith had many adherents. He is said to have entertained at one time the terrible project of eliminating this source of danger in Shensi and Kansuh by killing every Mussulman found there, but whether he really contemplated an act so foreign to the general character of his procedure is doubtful. The broad fact is that the Central Government of China has never persecuted Mohammedans or discriminated against them. They are allowed to present themselves at the examinations for civil or military appointments, and the successful candidates obtain office as readily as their Chinese competitors.

{{استشهاد بكتاب}}: صيانة CS1: location (link)Original from Princeton University - Arthur Evans Moule (1914)، The Chinese people: a handbook on China ...، LONDON NORTHUMBERLAND AVENUE, W.C.: Society for promoting Christian knowledge، ص. 317، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 14 ديسمبر 2011،

ough the actual date and circumstances of the introduction of Islam into China cannot be traced with certainty further back than the thirteenth century, yet the existence of settlements of foreign Moslems with their Mosques at Ganfu (Canton) during the T'ang dynasty (a.d. 618—907) is certain, and later they spread to Ch'uan-chou and to Kan-p'u, Hangchow, and perhaps to Ningpo and Shanghai. These were not preaching or proselytising inroads, but commercial enterprises, and in the latter half of the eighth century there were Moslem troops in Shensi, 3,000 men, under Abu Giafar, coming to support the dethroned Emperor in A.d. 756. In the thirteenth century the influence of individual Moslems was immense, especially that of the Seyyid Edjell Shams ed-Din Omar, who served the Mongol Khans till his death in Yunnan A.d. 1279. His family still exists in Yunnan, and has taken a prominent part in Moslem affairs in China. The present Moslem element in China is most numerous in Yunnan and Kansu; and the most learned Moslems reside chiefly in Ssuch'uan, the majority of their books being printed in the capital city, Ch'eng-tu. Kansu is perhaps the most dominantly Mohammedan province in China, and here many different sects are found, and mosques with minarets used by the orthodox muezzin calling to prayer, and in one place veiled women are met with. These, however, are not Turks or Saracens, but for the most part pure Chinese. The total Moslem population is probably under 4,000,000, though other statistical estimates, always uncertain in China, vary from thirty to ten millions; but the figures given here are the most reliable at present obtainable, and when it is remembered that Islam in China has not been to any great extent a preaching or propagandist power by force or the sword, it is difficult to understand the survival and existence of such a large number as that, small, indeed, compared with former estimates, but surely a very large and vigorous element.

Original from the University of California - Herbert Allen Giles (1886)، A glossary of reference on subjects connected with the Far East (ط. 2)، HONGKONG: Messrs. Lane، ص. 141، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 14 ديسمبر 2011،

MAHOMEDANS: IEJ Iej. First settled in China in the Year of the Mission, A.D. 628, under Wahb-Abi-Kabcha a maternal uncle of Mahomet, who was sent with presents to the Emperor. Wahb-Abi-Kabcha travelled by sea to Cantoa, and thence overland to Si-ngan Fu, the capital, where he was well received. The first mosque was built at Canton, where, after several restorations, it still exists. Another mosque was erected in 742, but many of these M. came to China simply as traders, and by and by went back to their own country. The true stock of the present Chinese Mahomedans was a small army of 4,000 Arabian soldiers sent by the Khaleef Abu Giafar in 755 to aid in putting down a rebellion. These soldiers had permission to settle in China, where they married native wives; and three centuries later, with the conquests of Genghis Khan, largo numbers of Arabs penetrated into the Empire and swelled the Mahomedan community.

Original from the New York Public Library - Herbert Allen Giles (1926)، Confucianism and its rivals، Forgotten Books، ص. 139، ISBN 1-60680-248-8، مؤرشف من الأصل في 8 أغسطس 2020، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 14 ديسمبر 2011،

In7= 789 the Khalifa Harun al Raschid dispatched a mission to China, and there had been one or two less important missions in the seventh and eighth centuries; but from 879, the date of the Canton massacre, for more than three centuries to follow, we hear nothing of the Mahometans and their religion. They were not mentioned in the edict of 845, which proved such a blow to Buddhism and Nestorian Christianityl perhaps because they were less obtrusive in the propagation of their religion, a policy aided by the absence of anything like a commercial spirit in religious matters.

- Confucianism and its Rivals، Forgotten Books، ص. 223، ISBN 1-4510-0849-X، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 14 ديسمبر 2011،

The first mosque built at Canton, where, after several restorations, it may still be seen. The minaret, known as the Bare Pagoda, to distinguish it from a much more ornamental Buddhist pagoda near by, dates back to 850. There must at that time have been a considerable number of Mahometans in Canton, thought not so many as might be supposed if reliance could be placed on the figures given in reference to a massacre which took place in 879. The fact is that most of these Mahometans went to China simply as traders ; they did not intend to settle permanently in the country, and when business permitted, they returned to their old haunts. About two thousand Mussulman families are still to be found at Canton, and a similar number at Foochow ; descendants, perhaps, of the old sea-borne contingents which began to arrive in the seventh and eighth centuries. These remnants have nothing to do with the stock from which came the comparatively large Mussulman communities now living and practising their religion in the provinces of Ssŭch'uan, Yünnan, and Kansuh. The origin of the latter was as follows. In A.D. 756 the Khalifa Abu Giafar sent a small army of three thousand Arab soldiers to aid in putting down a rebellion.

- Everett Jenkins (1999)، The Muslim diaspora: a comprehensive reference to the spread of Islam in Asia, Africa, Europe, and the Americas (ط. illustrated)، McFarland، ج. 1 of The Muslim Diaspora، ص. 61، ISBN 0-7864-0431-0، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 14 ديسمبر 2011،

China • Arab troops were dispatched by Abu Gia- far to China.

(Original from the University of Michigan ) - Carné (1872)، Travels in Indo-China and the Chinese Empire، Chapman and Hall، ص. 295، مؤرشف من الأصل في 8 أغسطس 2021، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 14 ديسمبر 2011،

abu giafar chinese.

- Stanley Ghosh (1961)، Embers in Cathay، Doubleday، ص. 60، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 14 ديسمبر 2011،

During the reign of Abbassid Caliph Abu Giafar in the middle of the eighth century, many Arab soldiers evidently settled near the garrisons on the Chinese frontier.

(Original from the University of Michigan, Library of Catalonia ) - Heinrich Hermann (1912)، Chinesische Geschichte (باللغة الألمانية)، D. Gundert، ص. 77، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 14 ديسمبر 2011،

785, als die Tibeter in China einfielen, sandte Abu Giafar eine zweite Truppe, zu deren Unterhalt die Regierung die Teesteuer verdoppelte. Sie wurde ebenso angesiedelt. 787 ist von 4000 fremden Familien aus Urumtsi und Kaschgar in Si-Ngan die Rede: für ihren Unterhalt wurden 500000 Taël

(Original from the University of California ) - Deutsche Literaturzeitung für Kritik der Internationalen Wissenschaft, Volume 49, Issues 27-52، Weidmannsche Buchhandlung، 1928، ص. 1617، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 14 ديسمبر 2011،

Die Fassung, daß mohammedanische Soldaten von Turkestan ihre Religion nach China gebracht hätten, ist irreführend. Das waren vielmehr die 4000 Mann, die der zweite Kalif Abu Giafar 757 schickte, ebenso wie die Hilfstruppen 785 bei dem berühmten Einfali der Tibeter. Die Uiguren waren damals noch

(Original from Indiana University ) - Samy S. Swayd (2006)، Historical dictionary of the Druzes (ط. illustrated)، Scarecrow Press، ج. 3 of Historical dictionaries of people and cultures، ص. xli، ISBN 0-8108-5332-9، مؤرشف من الأصل في 10 أغسطس 2021، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 4 أبريل 2012،

The fifth caliph, al-'Aziz bi-Allah (r.975-996). . . In his time, the Fatimi "Call" or "Mission" (Da'wa) reached as far east as India and northern China.

- E. J. van Donzel (1994)، E. J. van Donzel (المحرر)، Islamic desk reference (ط. illustrated)، BRILL، ص. 67، ISBN 90-04-09738-4، مؤرشف من الأصل في 23 ديسمبر 2021، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 26 ديسمبر 2011،

China (A. al-Sin):. . .After the coming of Islam, the existing trade was continued by the peoples of the South Arabian coast and the Persian Gulf, but the merchants remained on the coast.

- Ralph Kauz (2010)، Ralph Kauz (المحرر)، Aspects of the Maritime Silk Road: From the Persian Gulf to the East China Sea، Otto Harrassowitz Verlag، ج. 10 of East Asian Economic and Socio-cultural Studies - East Asian Maritime History، ص. 130، ISBN 978-3-447-06103-2، مؤرشف من الأصل في 6 أغسطس 2021، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 26 ديسمبر 2011.

- "National Geographic Magazine"، ngm.nationalgeographic.com، مؤرشف من الأصل في 19 نوفمبر 2016، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 18 أبريل 2018.

- Masumi, Matsumoto، "The completion of the idea of dual loyalty towards China and Islam"، مؤرشف من الأصل في 24 يوليو 2011، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 28 يونيو 2010.

- Hsiao-ting Lin (2010)، Modern China's Ethnic Frontiers: A Journey to the West، Taylor & Francis، ص. 90، ISBN 978-0-415-58264-3، مؤرشف من الأصل في 27 يوليو 2020، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 28 يونيو 2010.

- "中国首批留埃学生林仲明"، مؤرشف من الأصل في 17 يوليو 2021.

- "الصين وجامعة الدول العربية"، China–Arab States Cooperation Forum، 09 يناير 2010، مؤرشف من الأصل في 09 يناير 2010، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 09 سبتمبر 2021.

- Yellinek, Roie؛ Hoffman، "The Middle East and China: Trust in the time of COVID-19"، Middle East Institute (باللغة الإنجليزية)، مؤرشف من الأصل في 17 ديسمبر 2021، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 13 مايو 2020.

- Lawler, Dave (02 يوليو 2020)، "The 53 countries supporting China's crackdown on Hong Kong"، Axios (باللغة الإنجليزية)، مؤرشف من الأصل في 12 يناير 2022، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 03 يوليو 2020.

- Yellinek Roie, Chen Elizabeth، "The "22 vs. 50" Diplomatic Split Between the West and China Over Xinjiang and Human Rights"، Jamestown (باللغة الإنجليزية)، مؤرشف من الأصل في 20 يناير 2022، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 08 نوفمبر 2020.

- Yellinek, Roie؛ Mann؛ Lebel (01 نوفمبر 2020)، "Chinese Soft-Power in the Arab world – China's Confucius Institutes as a central tool of influence"، Comparative Strategy، 39 (6): 517–534، doi:10.1080/01495933.2020.1826843، ISSN 0149-5933، مؤرشف من الأصل في 1 فبراير 2022.

- Retroactively known as “Communist China” or “Red China”, but it is commonly known as “China”.

- Also known as “Formosa”. It is historically sometimes referred to as “Nationalist China”, “Free China” or simply known as “China” until the 1970s. See الوضع السياسي في تايوان and سياسة الصين الواحدة.

- "Number of Villages, Neighborhoods, Households and Resident Population"، MOI Statistical Information Service، مؤرشف من الأصل في 5 فبراير 2018، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 02 فبراير 2014.

- "Arab League Online - View the Presentation of the Arab League - Sportwetten & beste Singlebörse im Vergleich"، www.arableagueonline.org، مؤرشف من الأصل في 20 يوليو 2011، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 18 أبريل 2018.

روابط خارجية

- بوابة الوطن العربي

- بوابة الصين

- بوابة تايوان

.jpg.webp)

.svg.png.webp)