Tian

Tiān (天) is one of the oldest Chinese terms for heaven and a key concept in Chinese mythology, philosophy, and religion. During the Shang dynasty (17th―11th century BCE), the Chinese referred to their supreme god as Shàngdì (上帝, "Lord on High") or Dì (帝, "Lord").[1] During the following Zhou dynasty, Tiān became synonymous with this figure. Before the 20th century, worship of Tiān was an orthodox state religion of China.

| Tian | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Chinese Bronze script character for tiān. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 天 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | heaven(s) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | thiên | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 天 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 천 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 天 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 天 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kana | てん | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Chinese folk religion |

|---|

|

In Taoism and Confucianism, Tiān (the celestial aspect of the cosmos, often translated as "Heaven") is mentioned in relationship to its complementary aspect of Dì (地, often translated as "Earth").[2][3] They are thought to maintain the two poles of the Three Realms (三界) of reality, with the middle realm occupied by Humanity (人, rén), and the lower world occupied by demons (魔, mó) and "ghosts", the damned, (鬼, guǐ).[4] Tiān was variously thought as a "supreme power reigning over lesser gods and human beings"[5][6] that brought "order and calm...or catastrophe and punishment",[7] a god,[8][9] destiny,[9][7] an "impersonal" natural force that controlled various events,[5][9] a holy world or afterlife containing other worlds or afterlives,[10][11] or one or more of these.[5]

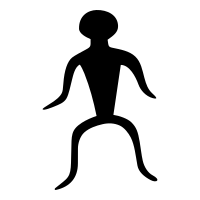

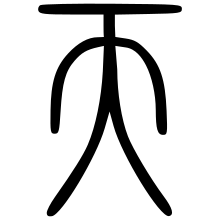

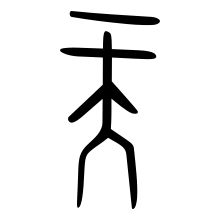

Characters

The modern Chinese character 天 and early seal script both combine dà 大 "great; large" and yī 一 "one", but some of the original characters in Shāng oracle bone script and Zhōu bronzeware script anthropomorphically portray a large head on a great person. The ancient oracle and bronze ideograms for dà 大 depict a stick figure person with arms stretched out denoting "great; large". The oracle and bronze characters for tiān 天 emphasize the cranium of this "great (person)", either with a square or round head, or head marked with one or two lines. Schuessler notes the bronze graphs for tiān, showing a person with a round head, resemble those for dīng 丁 "4th Celestial stem", and suggests "The anthropomorphic graph may or may not indicate that the original meaning was 'deity', rather than 'sky'."[12]

Two variant Chinese characters for tiān 天 "heaven" are 二人 (written with 二 er "two" and 人 ren "human") and the Daoist coinage 靝[13] (with 青 qīng "blue" and 氣 "qì", i.e., "blue sky").

Pronunciation and etymology

The Modern Standard Chinese pronunciation of 天 "sky, heaven; heavenly deity, god" is tiān [tʰi̯ɛn˥] in level first tone. The character is read as Cantonese tin1; Taiwanese thiN1 or thian1; Vietnamese thiên; Korean cheon or ch'ŏn (천); and Japanese ten in On'yomi (borrowed Chinese reading) and ama- (bound), ame (free), or sora in Kun'yomi (native Japanese reading).

Tiān 天 reconstructions in Middle Chinese (c. 6th–10th centuries CE) include t'ien,[14] t'iɛn,[15] tʰɛn > tʰian,[16] and then.[17] Reconstructions in Old Chinese (c. 6th–3rd centuries BCE) include *t'ien,[14] *t'en,[18] *hlin,[19] *thîn,[20] and *l̥ˤin.[21]

For the etymology of tiān, Schuessler links it with the Mongolian word tengri "sky, heaven, heavenly deity" or the Tibeto-Burman words taleŋ (Adi) and tǎ-lyaŋ (Lepcha), both meaning "sky".[12] He also suggests a likely connection between Chinese tiān 天, diān 巔 "summit, mountaintop", and diān 顛 "summit, top of the head, forehead", which have cognates such as Zemeic Naga tiŋ "sky".[22] However, other reconstructions of 天's OC pronunciation *qʰl'iːn [23] or *l̥ˤi[n] [24] reconstructed a voiceless lateral onset, either a cluster or a single consonant, respectively. Baxter & Sagart pointed to attested dialectal differences in Eastern Han Chinese, the use of 天 as a phonetic component in phono-semantic compound Chinese characters, and the choice of 天 to transcribe foreign syllables, all of which prompted them to conclude that, around 200 CE, 天's onset had two pronunciations: coronal *tʰ & dorsal *x, both of which likely originated from an earlier voiceless lateral *l̥ˤ.[25]

Compounds

Tiān is one of the components in hundreds of Chinese compounds. Some significant ones include:

- Tiānmìng (天命 "Mandate of Heaven") "divine mandate, God's will; fate, destiny; one's lifespan"

- Tiānwèn (simplified Chinese: 天问; traditional Chinese: 天問; pinyin: Tiānwèn), the Heavenly Questions section of the Chǔ Cí.

- Tiānzĭ (天子 "Son of Heaven"), an honorific designation for the "Emperor; Chinese sovereign" (Tiānzǐ accounts for 28 of the 140 tiān occurrences in the Shī Jīng above.)

- Tiānxià (天下, lit. "all under heaven") "the world, earth; China"

- Tiāndì (天地, lit "heaven and earth") "the world; the universe."

- Xíngtiān (刑天) An early mythological hero who fought against Heaven, despite being decapitated.

- Tiānfáng (天房, lit. "House of Heaven") A Chinese name for the Kaaba, from Bayt Allah (Arabic: بَيْت ٱللَّٰه, lit. 'House of God').

Chinese interpretations

"Lord Heaven" and "Jade Emperor" were terms for a supreme deity in Confucianism and Taoism who was an anthropromorphized Tian,[26] and some conceptions of it thought of the names as synonymous.

Tiān was viewed as "the dwelling place of God, gods,...other superhuman beings and the...state of being of the saved[27]".[9] It was also viewed as "the guardian of both the moral laws of mankind and the physical laws of nature...and is synonymous with the divine will."[9]

In Chinese culture, heaven tends to be "synonymous with order", "containing the blueprints for creation", "the mandate by which earthly rulers govern, and the standards by which to measure beauty, goodness, and truth."[27]

Zhou dynasty nobles made the worship of heaven a major part of their political philosophy and viewed it as "many gods" who embodied order and kingship, as well as the mandate of heaven.[28]

Confucianism

"Confucianism has a religious side with a deep reverence for Heaven and Earth (Di), whose powers regulate the flow of nature and influence human events."[3] Yin and yang are also thought to be integral to this relationship and permeate both, as well as humans and man-made constructs.[3] This "cosmos" and its "principles" is something that "[t]he ways of man should conform to, or else" frustration will result.[3]

Many Confucianists, both historically and in current times, use the I Ching to divine events through the changes of Tiān and other "natural forces".[3] Historical and current Confucianists were/are often environmentalists[29] out of their respect for Heaven and the other aspects of nature and the "Principle" that comes from their unity and, more generally, harmony as a whole, which is "the basis for a sincere mind."[3]

The Emperor of China as Tianzi was formerly vital to Confucianism.[7]

Mount Tai is seen as a sacred place in Confucianism and was traditionally the most revered place where Chinese emperors offered sacrifices to heaven and earth.[30]

Confucius

The concept of Heaven (Tiān, 天) is pervasive in Confucianism. Confucius had a deep trust in Heaven and believed that Heaven overruled human efforts. He also believed that he was carrying out the will of Heaven, and that Heaven would not allow its servant, Confucius, to be killed until his work was done.[31] Many attributes of Heaven were delineated in his Analects.

Confucius honored Heaven as the supreme source of goodness:

The Master said, "Great indeed was Yao as a sovereign! How majestic was he! It is only Heaven that is grand, and only Yao corresponded to it. How vast was his virtue! The people could find no name for it. How majestic was he in the works which he accomplished! How glorious in the elegant regulations which he instituted!"[32]

Confucius felt himself personally dependent upon Heaven: "Wherein I have done improperly, may Heaven reject me! may Heaven reject me!"[33]

Confucius believed that Heaven cannot be deceived:

The Master being very ill, Zi Lu wished the disciples to act as ministers to him. During a remission of his illness, he said, "Long has the conduct of You been deceitful! By pretending to have ministers when I have them not, whom should I impose upon? Should I impose upon Heaven? Moreover, than that I should die in the hands of ministers, is it not better that I should die in the hands of you, my disciples? And though I may not get a great burial, shall I die upon the road?"[34]

Confucius believed that Heaven gives people tasks to perform to teach them of virtues and morality:

The Master said, "At fifteen, I had my mind bent on learning. At thirty, I stood firm. At forty, I had no doubts. At fifty, I knew the decrees of Heaven. At sixty, my ear was an obedient organ for the reception of truth. At seventy, I could follow what my heart desired, without transgressing what was right."[35]

He believed that Heaven knew what he was doing and approved of him, even though none of the rulers on earth might want him as a guide:

The Master said, "Alas! there is no one that knows me." Zi Gong said, "What do you mean by thus saying - that no one knows you?" The Master replied, "I do not murmur against Heaven. I do not grumble against men. My studies lie low, and my penetration rises high. But there is Heaven - that knows me!" [36]

Perhaps the most remarkable saying, recorded twice, is one in which Confucius expresses complete trust in the overruling providence of Heaven:

The Master was put in fear in Kuang. He said, "After the death of King Wen, was not the cause of truth lodged here in me? If Heaven had wished to let this cause of truth perish, then I, a future mortal, should not have got such a relation to that cause. While Heaven does not let the cause of truth perish, what can the people of Kuang do to me?" [37]

Mozi

For Mozi, Heaven is the divine ruler, just as the Son of Heaven is the earthly ruler. Mozi believed that spirits and minor demons exist or at least rituals should be performed as if they did for social reasons, but their function is to carry out the will of Heaven, watching for evil-doers and punishing them. Mozi taught that Heaven loves all people equally and that each person should similarly love all human beings without distinguishing between his own relatives and those of others.[38] Mozi criticized the Confucians of his own time for not following the teachings of Confucius. In Mozi's Will of Heaven (天志), he writes:

Moreover, I know Heaven loves men dearly not without reason. Heaven ordered the sun, the moon, and the stars to enlighten and guide them. Heaven ordained the four seasons, Spring, Autumn, Winter, and Summer, to regulate them. Heaven sent down snow, frost, rain, and dew to grow the five grains and flax and silk that so the people could use and enjoy them. Heaven established the hills and rivers, ravines and valleys, and arranged many things to minister to man's good or bring him evil. He appointed the dukes and lords to reward the virtuous and punish the wicked, and to gather metal and wood, birds and beasts, and to engage in cultivating the five grains and flax and silk to provide for the people's food and clothing. This has been so from antiquity to the present."[39]

Schools of cosmology

There are three major schools on the structure of tian. Most other hypothesis were developed from them.

- Gaitian shuo (蓋天說) "Canopy-Heavens hypothesis" originated from the text Zhoubi Suanjing. The earth is covered by a material tian.

- Huntian shuo (渾天說) "Egg-like hypothesis". The earth surrounded by a tian sphere rotating over it. The celestial bodies are attached to the tian sphere. (See Zhang Heng § Astronomy and mathematics, Chinese creation myth.)

- Xuanye shuo (宣夜說) "Firmament hypothesis". The tian is an infinite space. The celestial bodies were light matters floating on it moved by Qi. A summary by Ji Meng (郗萌) is in the astronomical chapters of the Book of Jin.

Tiān schools influenced popular conception of the universe and earth until the 17th century, when they were replaced by cosmological science imported from Europe.[40]

Sometimes the sky is divided into Jiutian (九天) "the nine sky divisions", the middle sky and the eight directions.

Buddhism

The Tian are the heaven worlds and pure lands in Buddhist cosmology.

Some devas are also called Tian.

Taoism

The number of vertical heaven layers in Taoism is different. A common belief in Taoism is that there were 36 Tiān "arranged on six levels" that have "different deities".[7] The highest heaven is the "Great Web" which was sometimes said to be where Yuanshi Tianzun lived.[7]

After death, some Taoists were thought to explore "heavenly realms" and/or become Taoist immortals.[10][41] These immortals could be good or evil,[42] and there were sometimes rivalries between them.

Some heavens in Taoism were thought to be evil, as in Shangqing Daoism,[43] although Tiān was mostly thought of as a force for good.[44]

Heaven is sometimes seen as synonymous with the Dao or a natural energy that can be accessed by living in accordance with the Dao.[27]

A Tao realm inconceivable and incomprehensible by normal humans and even Confucius and Confucianists[45] was sometimes called "the Heavens".[46] Higher, spiritual versions of Daoists such as Laozi were thought to exist in there when they were alive and absorb "the purest Yin and Yang",[46] as well as xian who were reborn into it after their human selves' spirits were sent there. These spiritual versions were thought to be abstract beings that can manifest in that world as mythical beings such as xian dragons who eat yin and yang energy and ride clouds and their qi.[46]

Chinese folk religion

Some tiān in Chinese folk religion were thought to be many different or a hierarchy of multiple, sphere-like[40] realms that contained morally ambiguous creatures and spirits such as huli jing[11] and fire-breathing dragons.[47]

The Tao realm was thought to exist by many ancient folk religion practitioners.[46]

Yiguandao

In Yiguandao, Tian is divided into three vertical worlds. Li Tian (理天) "heaven of truth", Qi Tian (氣天) "heaven of spirit" and Xiang Tian (象天) "heaven of matter".

Japanese interpretations

In some cases, the heavens in Shinto were thought to be a hierarchy of multiple, sphere-like realms that contained kami such as fox spirits.[11]

Myths about the kami were told "of their doings on Earth and in heaven."[48] Heaven was thought to be a clean and orderly place for nature gods in Shinto.[48]

Meanings

The semantics of tian developed diachronically. The Hanyu dazidian, an historical dictionary of Chinese characters, lists 17 meanings of tian 天, translated below.

- Human forehead; head, cranium. 人的額部; 腦袋.

- Anciently, to tattoo/brand the forehead as a kind of punishment. 古代一種在額頭上刺字的刑罰.

- The heavens, the sky, the firmament. 天空.

- Celestial bodies; celestial phenomena, meteorological phenomena. 天體; 天象.

- Nature, natural. A general reference to objective inevitability beyond human will. 自然. 泛指不以人意志為轉移的客觀必然性.

- Natural, innate; instinctive, inborn. 自然的; 天性的.

- Natural character/quality of a person or thing; natural instinct, inborn nature, disposition. 人或物的自然形質; 天性.

- A reference to a particular sky/space. 特指某一空間.

- Season; seasons. Like: winter; the three hot 10-day periods [following the summer solstice]. 時令; 季節. 如: 冬天; 三伏天.

- Weather; climate. 天氣; 氣候.

- Day, time of one day and night, or especially the time from sunrise to sunset. Like: today; yesterday; busy all day; go fishing for three days and dry the nets for two [a xiehouyu simile for "unable to finish anything"]. 一晝夜的時間, 或專指日出到日落的時間. 如: 今天; 昨天; 忙了一天; 三天打魚, 兩天曬網.

- God, heaven, celestial spirit, of the natural world. 天神, 上帝, 自然界的主宰者.

- Heaven, heavenly, a superstitious person's reference to the gods, Buddhas, or immortals; or to the worlds where they live. Like: go to heaven ["die"]; heavenly troops and heavenly generals ["invincible army"]; heavenly goddesses scatter blossoms [a Vimalakirti Sutra reference to "Buddha's arrival"]. 迷信的人指神佛仙人或他們生活的那個世界. 如: 歸天; 天兵天將; 天女散花.

- Anciently, the king, monarch, sovereign; also referring to elders in human relationships. 古代指君王; 也指人倫中的尊者.

- Object upon which one depends or relies. 所依存或依靠的對象.

- Dialect. A measure of land [shang, about 15 acres]. 方言. 垧.

- A family name, surname. 姓.

The Chinese philosopher Feng Youlan differentiates five different meanings of tian in early Chinese writings:

(1) A material or physical T'ien or sky, that is, the T'ien often spoken of in apposition to earth, as in the common phrase which refers to the physical universe as 'Heaven and Earth' (T'ien Ti 天地).

(2) A ruling or presiding T'ien, that is, one such as is meant in the phrase, 'Imperial Heaven Supreme Emperor' (Huang T'ien Shang Ti), in which anthropomorphic T'ien and Ti are signified.

(3) A fatalistic T'ien, equivalent to the concept of Fate (ming 命), a term applied to all those events in human life over which man himself has no control. This is the T'ien Mencius refers to when he says: "As to the accomplishment of a great deed, that is with T'ien" ([Mencius], Ib, 14).

(4) A naturalistic T'ien, that is, one equivalent to the English word Nature. This is the sort of T'ien described in the 'Discussion on T'ien' in the [Hsün Tzǔ] (ch. 17).(5) An ethical T'ien, that is, one having a moral principle and which is the highest primordial principle of the universe. This is the sort of T'ien which the [Chung Yung] (Doctrine of the Mean) refers to in its opening sentence when it says: "What T'ien confers (on man) is called his nature."[49]

The Oxford English Dictionary enters the English loanword t'ien (also tayn, tyen, tien, and tiān) "Chinese thought: Heaven; the Deity." The earliest recorded usages for these spelling variants are: 1613 Tayn, 1710 Tien, 1747 Tyen, and 1878 T'ien.

In early Chinese writings, tiān was thought to be a subservient location that a higher deity owned,[50] and Shangdi was thought by some to be this being.

Interpretation by Western Sinologists

The sinologist Herrlee Creel, who wrote a comprehensive study called "The Origin of the Deity T'ien", gives this overview.

For three thousand years it has been believed that from time immemorial all Chinese revered T'ien 天, "Heaven," as the highest deity, and that this same deity was also known as Shangdi, Ti 帝, or Shang Ti 上帝. But the new materials that have become available in the present century, and especially the Shang inscriptions, make it evident that this was not the case. It appears rather that T'ien is not named at all in the Shang inscriptions, which instead refer with great frequency to Ti or Shang Ti. T'ien appears only with the Chou, and was apparently a Chou deity. After the conquest the Chou considered T'ien to be identical with the Shang deity Ti (or Shang Ti), much as the Romans identified the Greek Zeus with their Jupiter.[51]

Creel refers to the historical shift in ancient Chinese names for "god"; from Shang oracles that frequently used di and shangdi and rarely used tian to Zhou bronzes and texts that used tian more frequently than its synonym shangdi.

First, Creel analyzes all the tian and di occurrences meaning "god; gods" in Western Zhou era Chinese classic texts and bronze inscriptions. The Yi Jing "Classic of Changes" has 2 tian and 1 di; the Shi Jing "Classic of Poetry" has 140 tian and 43 di or shangdi; and the authentic portions of the Shu Jing "Classic of Documents" have 116 tian and 25 di or shangdi. His corpus of authenticated Western Zhou bronzes mention tian 91 times and di or shangdi only 4 times. Second, Creel contrasts the disparity between 175 occurrences of di or shangdi on Shang era oracle inscriptions with "at least" 26 occurrences of tian. Upon examining these 26 oracle scripts that scholars (like Guo Moruo) have identified as tian 天 "heaven; god",[52] he rules out 8 cases in fragments where the contextual meaning is unclear. Of the remaining 18, Creel interprets 11 cases as graphic variants for da "great; large; big" (e.g., tian i shang 天邑商 for da i shang 大邑商 "great settlement Shang"), 3 as a place name, and 4 cases of oracles recording sacrifices yu tian 于天 "to/at Tian" (which could mean "to Heaven/God" or "at a place called Tian".)[53]

The Shu Jing chapter "Tang Shi" (湯誓 "Tang's Speech") illustrates how early Zhou texts used tian "heaven; god" in contexts with shangdi "god". According to tradition, Tang of Shang assembled his subjects to overthrow King Jie of Xia, the infamous last ruler of the Xia Dynasty, but they were reluctant to attack.

The king said, "Come, ye multitudes of the people, listen all to my words. It is not I, the little child [a humble name used by kings], who dare to undertake what may seem to be a rebellious enterprise; but for the many crimes of the sovereign of Hsiâ [Xia] Heaven has given the charge [...] to destroy him. Now, ye multitudes, you are saying, 'Our prince does not compassionate us, but (is calling us) away from our husbandry to attack and punish the ruler of Hsiâ.' I have indeed heard these words of you all; but the sovereign of Hsiâ is an offender, and, as I fear God [shangdi], I dare not but punish him. Now you are saying, 'What are the crimes of Hsiâ to us?' The king of Hsiâ does nothing but exhaust the strength of his people, and exercise oppression in the cities of Hsiâ. His people have all become idle in his service, and will not assist him. They are saying, 'When will this sun expire? We will all perish with thee.' Such is the course of the sovereign of Hsiâ, and now I must go and punish him. Assist, I pray you, me, the one man, to carry out the punishment appointed by Heaven [tian]. I will greatly reward you. On no account disbelieve me; — I will not eat my words. If you do not obey the words which I have spoken to you, I will put your children with you to death; — you shall find no forgiveness."[54]

Having established that Tiān was not a deity of the Shang people, Creel proposes a hypothesis for how it originated. Both the Shang and Zhou peoples pictographically represented da 大 as "a large or great man". The Zhou subsequently added a head on him to denote tian 天 meaning "king, kings" (cf. wang 王 "king; ruler", which had oracle graphs picturing a line under a "great person" and bronze graphs that added the top line). From "kings", tiān was semantically extended to mean "dead kings; ancestral kings", who controlled "fate; providence", and ultimately a single omnipotent deity Tian "Heaven". In addition, tiān named both "the heavens" (where ancestral kings and gods supposedly lived) and the visible "sky".[55]

Another possibility is that Tiān may be related to Tengri and there was possibly a loan word from a prehistoric Central Asian language that contributed to the creation of the word.[56]

Kelly James Clark argued that Confucius himself saw Tiān as an anthropomorphic god that Clark hypothetically refers to as "Heavenly Supreme Emperor", although most other scholars on Confucianism disagree with this view.[57]

See also

- Amenominakanushi (天御中主), the Japanese concept of God as the ultimate creator

- Haneullim, the Sky God of Cheondoism

- Hongjun Laozu

- Names of God in China

- Shangdi

- Shen

- Taiyi Tianzun

- Tengri, the Turkic-Mongolic sky God

Tian related terms

- Tianxia (All under Heaven)

- Tian Chao (Dynasty of Heaven)

- Tian Kehan (Khan of Heaven)

- Tian Ming (Mandate of Heaven)

- Tian Zi (Son of Heaven)

- Tiandihui (Heaven and Earth Society)

- Tiandiism (Heavenly Deity religion)

- Tianzhu (Chinese Rites controversy)

References

Citations

- Stefon, Matt (2010-02-03). "Shangdi". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2023-05-01.

- Woodhead, Linda; Partridge, Christopher; Kawanami, Hiroko (2016). Religions in the Modern World (Third ed.). New York, NY: Routledge. pp. 147–148. ISBN 978-0-415-85881-6.

- Wilson, Andrew, ed. (1995). World Scripture: A Comparative Anthology of Sacred Texts (1st paperback ed.). St. Paul, Minnesota: Paragon House Publishers. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-55778-723-1.

- Woolf, Greg (2007). Ancient civilizations: the illustrated guide to belief, mythology, and art. Barnes & Noble. p. 212. ISBN 978-1-4351-0121-0.

- "tian". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2023-04-28.

- Harari, Yuval Noah (2015). Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. Translated by Harari, Yuval Noah; Purcell, John; Watzman, Haim. London: Penguin Random House UK. p. 219. ISBN 978-0-09-959008-8. OCLC 910498369.

- Storm, Rachel (2011). Sudell, Helen (ed.). Myths & Legends of India, Egypt, China & Japan (2nd ed.). Wigston, Leicestershire: Lorenz Books. p. 233.

- World Religions: Eastern Traditions. Edited by Willard Gurdon Oxtoby (2nd ed.). Don Mills, Ontario: Oxford University Press. 2002. p. 424. ISBN 0-19-541521-3. OCLC 46661540.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Carrasco et al. 1999, p. 1096.

- "xian". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2023-04-29.

- Carlson, Kathie; Flanagin, Michael N.; Martin, Kathleen; Martin, Mary E.; Mendelsohn, John; Rodgers, Priscilla Young; Ronnberg, Ami; Salman, Sherry; Wesley, Deborah A.; et al. (Authors) (2010). Arm, Karen; Ueda, Kako; Thulin, Anne; Langerak, Allison; Kiley, Timothy Gus; Wolff, Mary (eds.). The Book of Symbols: Reflections on Archetypal Images. Köln: Taschen. p. 280. ISBN 978-3-8365-1448-4.

- Schuessler (2007), p. 495

- Carrasco et al. 1999, p. 1068.

- Karlgren (1922)

- Zhou (1972)

- Pulleyblank (1991)

- Baxter (1992), Baxter & Sagart (2014)

- Zhou (1972)

- Baxter (1992)

- Schuessler (2007)

- Baxter & Sagart (2014)

- Schuessler (2007), p. 211; #6312 NEIA *t(s)iŋ celestial / sky / weath (provisional) at Sino-Tibetan Etymological Dictionary and Thesaurus

- Zhengzhang (2003)

- Baxter & Sagart (2011), p. 110

- Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 113–114

- World Religions: Eastern Traditions. Edited by Willard Gurdon Oxtoby (2nd ed.). Don Mills, Ontario: Oxford University Press. 2002. pp. 326, 393, 401. ISBN 0-19-541521-3. OCLC 46661540.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Zaleski, Carol (2023-05-12). "Heaven". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2023-05-15.

- Pearson, Patricia O'Connell; Holdren, John (May 2021). World History: Our Human Story. Versailles, Kentucky: Sheridan Kentucky. p. 98. ISBN 978-1-60153-123-0.

- Tucker, Mary Evelyn (1998). "Confucianism and Ecology: Potential and Limits". The Forum on Religion and Ecology at Yale. Yale University. Retrieved 2023-04-29.

- Guangwei, He; Hualing, Tong; Wenzhen, Yang; Zhenguo, Chang; Zeru, Li; Ruicheng, Dong; Weijan, Gong, eds. (1999). Spectacular China. Translated by Wusun, Lin; Zhongping, Wu. Cologne: Könemann. p. 42. ISBN 9783829010771.

- Analects 7.23

- Confucius & Legge (1893), p.214, VIII, xix

- Confucius & Legge (1893), p.193, VI, xxviii

- Confucius & Legge (1893), pp. 220-221, IX, xi

- Confucius & Legge (1893), p.146, book II, chapter iv

- Confucius & Legge (1893), 288-9, XIV, xxxv

- Confucius & Legge (1893), 217-8, 9.5 and 7.12

- Dubs (1960), pp. 163–172

- Mozi & Mei (1929), p. 145

- Liu, Shu-Chiu (2006-12-11). "Three early Chinese models". Asia-Pacific Forum on Science, Learning, and Teaching. Historical models and science instruction: A cross-cultural analysis based on students’ views. Education University of Hong Kong.

- Carrasco et al. 1999, p. 473.

- Helle, Horst J. (2017). "CHAPTER 7 Daoism: China's Native Religion". JSTOR. Brill. pp. 75–76. Retrieved 2023-06-07.

- Carrasco et al. 1999, p. 691.

- Dell, Christopher (2012). Mythology: The Complete Guide to our Imagined Worlds. New York: Thames & Hudson. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-500-51615-7.

- Wilson, Andrew, ed. (1995). World Scripture: A Comparative Anthology of Sacred Texts (1st paperback ed.). St. Paul, Minnesota: Paragon House Publishers. pp. 467–468. ISBN 978-1-55778-723-1.

- Minford, John (2018). Tao Te Ching: The Essential Translation of the Ancient Chinese Book of the Tao. New York: Viking Press. pp. ix–x. ISBN 978-0-670-02498-8.

- Hua, Sara Lynn (2016-06-28). "Difference Between A Chinese Dragon and A Western Dragon". TutorABC Chinese China Expats & Culture Blog. Retrieved 2023-05-18.

- Stevenson, Jay (2000). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Eastern Philosophy. Indianapolis: Alpha Books. p. 170. ISBN 9780028638201.

- Feng (1952), p. 31

- Szostak, Rick (2020-10-22). Making Sense of World History. London: Routledge. p. 321. doi:10.4324/9781003013518. ISBN 9781003013518.

- Creel (1970), p. 493

- Creel (1970), pp. 494–5

- Creel (1970), pp. 464–75

- Legge (1865), pp. 173–5

- Creel (1970), pp. 501–6

- Müller (1870)

- "Searching for the Ineffable: Classical Theism and Eastern Thought about God". Classical Theism: New Essays on the Metaphysics of God. Edited by Jonathan Fuqua and Robert C. Koons. Routledge. 2023-02-10. ISBN 978-1-000-83688-2. OCLC 1353836889.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)

Sources

- Baxter, William H. (1992). A Handbook of Old Chinese Phonology. Mouton de Gruyter.

- Baxter, William; Sagart, Lauren (2011). "Baxter–Sagart Old Chinese Reconstruction" (pdf). Archived from the original on 27 September 2013.

- Baxter, William; Sagart, Lauren (2014). Old Chinese: A New Reconstruction (PDF). Oxford University Press. pp. 113–114. Supplemental materials available at their webpage.

- Carrasco, David; Warmind, Morten; Hawley, John Stratton; Reynolds, Frank; Giarardot, Norman; Neusner, Jacob; Pelikan, Jaroslav; Campo, Juan; Penner, Hans; et al. (Authors) (1999). Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions. Edited by Wendy Doniger. United States: Merriam-Webster. ISBN 9780877790440.

- Chang, Ruth H. (2000). "Understanding Di and Tian: Deity and Heaven From Shang to Tang". Sino-Platonic Papers. 108: 1–54.

- Creel, Herrlee G. (1970). The Origins of Statecraft in China. The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-12043-0.

- Dubs, Homer H. (1960). "Theism and Naturalism in Ancient Chinese Philosophy". Philosophy East and West. 9 (3–4): 163–172. doi:10.2307/1397096. JSTOR 1397096.

- Feng, Yu-Lan (1952). A History of Chinese Philosophy, Vol. I. The Period of the Philosophers. Translated by Bodde, Derk. Princeton University Press.

- Karlgren, Bernhard (1922). "The reconstruction of Ancient Chinese". T'oung Pao. 21: 1–42. doi:10.1163/156853222X00015.

- The Chinese Classics, Vol. III, The Shoo King. Translated by Legge, James. Oxford University Press. 1865 – via Internet Archive.

- Confucius (1893). The Chinese Classics, Vol. I, The Confucian Analects, the Great Learning, and the Doctrine of the Mean. Translated by Legge, James. Oxford University Press – via Internet Archive.

- Mozi (1929). The Ethical and Political Works of Motse. Translated by Mei, Y. P. London: Probsthain.

- Müller, Friedrich Max (1870). Lectures on the Science of Religion. New York, C. Scribner and company.

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G. (1991). A Lexicon of Reconstructed Pronunciation in Early Middle Chinese, Late Middle Chinese and Early Mandarin. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-0366-3.

- Schuessler, Axel (2007). ABC Etymological Dictionary of Old Chinese. University of Hawaii Press.

- Zhengzhang, Shangfang 鄭張尚芳 (2003). 上古音系 [Ancient Phonology]. Shanghai Education Press.

- Zhou, Fagao 周法高 (1972). "Shanggu Hanyu he Han-Zangyu" 上古漢語和漢藏語 [Ancient Chinese and Sino-Tibetan Languages]. Journal of the Institute of Chinese Studies of the Chinese University of Hong Kong (in Chinese). 5: 159–244.

External links

- Oracle, Bronze, and Seal characters for 天, Richard Sears