1557 influenza pandemic

In 1557, a pandemic strain of influenza emerged in Asia, then spread to Africa, Europe, and eventually the Americas. This flu was highly infectious and presented with intense, occasionally lethal symptoms. Medical historians like Thomas Short, Lazare Rivière and Charles Creighton gathered descriptions of catarrhal fevers recognized as influenza by modern physicians[1][2][3][4][5] attacking populations with the greatest intensity between 1557 and 1559.[6][7] The 1557 flu saw governments, for possibly the first time, inviting physicians to instill bureaucratic organization into epidemic responses.[4] It is also the first pandemic where influenza is pathologically linked to miscarriages,[8] given its first English names,[2][9] and is reliably recorded as having spread globally. Influenza caused higher burial rates, near-universal infection, and economic turmoil as it returned in repeated waves.

| 1557 flu pandemic | |

|---|---|

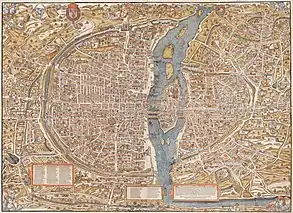

The 1557 flu pandemic spread across Asia, the Middle East, Africa, Europe, and the Americas. | |

| Disease | Influenza |

| Virus strain | unknown |

| Location | Asia, Africa, Europe, Americas |

| Date | 1557–1559 |

Deaths | unknown |

Asia

According to a European chronicler surnamed Fonseca who wrote Disputat. de Garotillo, the 1557 influenza pandemic first broke out in Asia.[10][11] The flu spread west along established trade and pilgrimage routes before reaching the Ottoman Empire and the Middle East. An epidemic of a flu-like illness is recorded for September 1557 in Portuguese Goa.[12]

Europe

_Europe_1559.jpg.webp)

In the summer of 1557 parts of Europe had just suffered outbreaks of plague,[2] typhus,[2] measles,[13] and smallpox[13] when influenza arrived from the Ottoman Empire and North Africa. The flu spread west through Europe aboard merchant ships in the Mediterranean Sea, again taking advantage of trade and pilgrimage routes. Death rates were highest in children, those with preexisting conditions,[14] the elderly,[15] and those who were bled.[16] Outbreaks were particularly severe in communities suffering from food scarcity. The epidemics of fevers and respiratory illness eventually became referred to as the new sickness in England,[2] new acquaintance[9] in Scotland, and coqueluche or simply catarrh by medical historians[17] in the rest of Europe. Because it afflicted entire populations at once in mass outbreaks, some contemporary scholars thought the flu was caused by stars,[11] contaminated vapors brought about by damp weather,[18][11] or the dryness of the air.[19][11] Ultimately the 1557 flu lasted in varying waves of intensity for around four years[7][20] in epidemics that increased European death rates, disrupted the highest levels of society, and frequently spread to other continents.

Ottoman Empire and East Europe

The flu pandemic first reached Europe in 1557 from the Ottoman Empire[21] along trade and shipping routes connected to Constantinople,[21] brought to Asia Minor by infected travelers from the Middle East. At the time, the Ottoman Empire's territory included most of the Balkans and Bulgaria. This gave influenza unrestricted access to Athens, Sofia, and Sarajevo as it spread throughout the empire. Influenza set sail from the capital, Constantinople, into the recently conquered North African territories of Tripoli (1551) and the Habesh (1557), from where it likely ricocheted to Malta from North Africa via merchant ships, as during the pandemic of 1510. On land, influenza spread north from the Ottoman Empire over Wallachia to the Kingdom of Poland and Grand Duchy of Lithuania before moving west into continental Europe.

Sicily, Italian States, and the Holy Roman Empire

Influenza arrived in the Kingdom of Sicily in June[22] at Palermo,[4] whence it spread across the island. Church services, Sicilian social life, and the economy were disrupted as the flu sickened a large portion of the population. The Sicilian Senate asked a well-known Palermitan physician named Giovanni Filippo Ingrassia to help combat the epidemic in an advisory capacity, which he accepted. Ingrassia approached epidemic responses as a collaboration between healthcare and government officials, and was the first known "health care professional" to propose that a system for monitoring epidemics of contagious catarrhal fevers would aid in early detection and epidemic control.[4]

Flu spread quickly from Sicily into the Kingdom of Naples on the lower part of the Italian Peninsula, moving upward along the coastline. In Urbino, Venetian court poet Bernardo Tasso, his son Torquato, and the occupants of a monastery fell sick "from hand to hand"[23] with influenza for four to five days. Though the epidemic left the entire city of Urbino ill,[23] most individuals recovered without complications. By the time Bernardo had traveled to northern Italy on August 3 the disease had already spread into the rest of Europe.[23] In Lombardy there was an outbreak of "suffocating catarrh" that could quickly become fatal. The symptoms were so severe that some members of the population suspected a mass poisoning had occurred.[24]

Padua began to see cases in August,[22] with sickness lasting into September.[13] German medical historian Justus Hecker writes that the young population of Padua had been reeling from a dual outbreak of measles and smallpox since the spring when a new illness, featuring extreme cough and headache, began to afflict the citizens in late summer. The illness was referred to as coqueluche.[13] Switzerland was also reached by the disease in August. "Catarrh" swept through the Swiss plateaus from August to September and almost disrupted the graduate studies of Swiss physician Felix Plater,[25] who was sickened by severe fits of coughing while a candidate for his doctorate.

Kingdom of France

._Line_engraving_by_C._Brunand._Wellcome_V0005033.jpg.webp)

French physician and medical historian Lazare Rivière documented an anonymous physician's descriptions of a flu outbreak[22] occurring in the Languedoc region of France in July 1557.[26] The disease, often called coqueluche by the French,[27][28] caused a severe outbreak in Nîmes that featured a fast onset of symptoms like headaches, fevers, loss of appetite, fatigue, and intense coughing.[29][27][22] Most of those who died from the disease did so on the fourth day, but some succumbed up to 11 days after first symptoms.[27][22] Across Languedoc influenza had a high mortality rate, with up to 200 people per day dying in Toulouse at the height of the region's epidemic.[30] Italian physician Francisco Vallerioli, known as François Valleriola, was a witness to the epidemic in France and described the 1557 flu's symptoms as featuring a fever, severe headache, intense coughing, shortness of breath, chills, hoarseness, and expulsion of phlegm after 7 to 14 days.[24][26] French lawyer Étienne Pasquier wrote that the disease began with a severe pain in the head and a 12- to 15-hour fever[31] while sufferers' noses "ran like a fountain."[32] Paris saw its judiciary disrupted when the Paris Law Court suspended its meetings to slow the spread of flu.[33] Medical historian Charles-Jacques Saillant described this influenza as especially fatal to those who were treated with bleeding[14] and very dangerous to children.[29]

Kingdoms of England and Scotland

The 1557 influenza severely impacted the British Isles. British medical historian Charles Creighton cited a contemporary writer, Wriothesley, who noted in 1557 "this summer reigned in England divers strange and new sicknesses, taking men and women in their heads; as strange agues and fevers, whereof many died."[34] 18th Century physician Thomas Short wrote that those who succumbed to the flu "were let blood of or had unsound viscera."[16] Flu blighted the army of Mary I of England by leaving her government unable to train sufficient reinforcements for the Earl of Rutland to protect Calais from an impending French assault,[35] and by January 1558 the Duke of Guise had claimed the under-protected[36] city in the name of France.

Influenza significantly contributed to England's unusually high death rates for 1557–58:[37][7] Data compiled on over 100 parishes in England found that the mortality rates increased by up to 60% in some areas during the flu epidemic,[7] even though diseases like true plague were not heavily present in England at the time.[2] Dr. Short found that the number of burials for market towns was much higher than christenings from 1557 to 1562.[2] For example, the annual number of burials in Tonbridge increased from 33 on average in 1556 to 61 in 1557, 105 in 1558, and 94 in 1559.[38] Before the flu epidemic, England had suffered from a poor harvest and widespread famine[39] that medical historian Thomas Short believed made the epidemic more deadly.[40]

Influenza returned in 1558. Contemporary historian John Stow wrote that during "winter the quarterne agues continued in like manner" to 1557's epidemic.[43] On 6 September 1558 the Governor of the Isle of Wight, Lord St. John, wrote in a despatch to Queen Mary about a highly-contagious illness afflicting more than half the people of Southampton, the Isle of Wight, and Portsmouth (places where Lord St. John had stationed troops).[2] A second despatch from 11 P.M. of 6 October indicated "from the mayor of Dover that there is no plague there, but the people that daily die are those that come out of the ships, and such poor people as come out of Calais, of the new sickness." One of the commissioners for the surrender of Calais found Sir William Pickering, former knight-marshal to King Henry VIII, "very sore of this new burning ague. He has had four sore fits, and is brought very low, and in danger of his life if they continue as they have done." Influenza began to move north through England, felling numerous farmers and leaving large quantities of grain unharvested[44] before it reached London around mid-late October. Queen Mary and Archbishop of Canterbury Reginald Pole, who had both been in poor health before flu broke out in London, likely died of influenza within 12 hours of each other on 17 November 1558.[41][45] Two of Mary's physicians died as well.[43] Ultimately around 8000 other Londoners likely died of influenza during the epidemic,[7] including many elders and parish priests.[43]

New waves of "agues" and fevers were recorded in England into 1559. These repeated outbreaks proved unusually deadly for populations already suffering from extensive rains and poor harvests. From 1557 to 1559 the nation's population contracted by 2%.[46] The sheer numbers of people dying from epidemics and famine in England caused economic inflation to flatten out.[47]

In the late 1550s the English language had not yet developed a proper name for the flu, despite previous epidemics. Thus 1557's epidemic was either described as a "plague" (like many epidemics with notable mortality), "ague" (most generally) or "new disease" in England. "The sweat" was one name used to describe the usually deadly, flu-like fevers and "agues" plaguing the English countryside from 1557 to 1558, despite no reliable records of sweating sickness after 1551. Doctor John Jones, a prominent 16th Century London physician, refers in his book Dyall of Agues to a "great sweat" during the reign of Queen Mary I of England.[2] After the 1557 pandemic English nicknames for the flu began to appear in letters, like "the new disease" in England and "the newe acquaintance" in Scotland. When the entire royal court of Mary, Queen of Scots was struck down with influenza in Edinburgh in November 1562, Lord Randolph described the outbreak as "a new disease, that is common in this town, called here 'the newe acquaintance,' which passed also through her whole court, neigh sparing lord, lady, nor damoysell, not so much as either French or English. It is a pain in their heads that have it, and a soreness in their stomachs, with a great cough, that remaineth with some longer with other short time, as it findeth apt bodies for the nature of the disease...There was not an appearance of danger, nor manie that died of the disease, except some old folks."[48] Mary Stuart herself spent six days sick in her bedchambers.[15][6]

Habsburg Netherlands

Habsburg Netherlands was also heavily impacted by the flu in October.[22] Dutch historian Petrus Forestus described an outbreak in Alkmaar where 2000 fell sick with flu and 200 perished[18][31] in a span of three weeks.[49] Forestus himself became sick with the flu and related that it "...began with a slight fever like a common catarrh, and showed its great malignancy only by degrees. Sudden fits of suffocation then came on, and the pain of the chest was so distressing that patients imagined they must die in the paroxysm. The complaint was increased still by a tight, convulsive cough. Death did not take place till the 9th or 14th day."[50] He further observed that the flu was very dangerous to pregnant women, killing at least eight such citizens in Alkmaar who contracted it.[22] Influenza's symptoms came on suddenly and attacked thousands of the city's residents at the same time.[51] Hunger likely contributed to a higher death toll, as the authorities had been struggling to provide food to the needy amid a severe bread shortage during the summer.[52] Attempting to explain the epidemic of fevers and respiratory illness affecting the Low Countries, Flemish physician Rembert Dodoens suggested that the mass outbreaks of illness were caused by a dry, hot summer following a very cold winter.[19]

Spain and Portugal

Spain was widely and severely impacted by influenza, which chroniclers recognized as a highly contagious catarrhal fever.[53][54] Influenza likely arrived in Spain around July, with the first cases being reported near Madrid in August.[55] British medical historian Thomas Short wrote that "At Mantua Carpentaria, three miles outside of Madrid, the first cases were reported...There it began with a roughness of the jaws, small cough, then a strong fever with a pain in the head, back, and legs. Some felt as though they were corded over the breast, with a weight at the stomach, all which continued to the third day at the furthest. Then the fever went off, with a sweat of bleeding at the nose. In some few, it turned to a pleurisy of fatal peripneumony."[56] Bloodletting greatly increased the risk of mortality, and it was observed in Mantua Carpentaria that "2000 were let blood of and all died."[57] The flu then entered Spain's capital city, where it rapidly spread to all parts of the Spanish mainland.

Cases expanded exponentially as merchants, pilgrims, and other travelers leaving Madrid transported the virus to cities and towns across the country. According to King Phillip II's doctor Luis de Mercado, "All the population was attacked the same day, and the same time of day. It was catarrh, marked by fever of the double tertian type, with such pernicious symptoms that many died."[58] The season's poor harvests and hunger in the Spanish population,[59] as well as negligent medical care, likely contributed to the severity of the influenza pandemic in Spain. Flu symptoms could be so intense that the region's physicians often distinguished it from other contagious, seasonal pneumonias that spread from East Europe.[60] Sixteenth century Spaniards frequently referred to any mass outbreak of deadly disease generically as a pestilencia,[61] and "plagues" are recognized as occurring in Valencia[62] and Granada[63] during the years 1557–59, despite pathological records of true plague (like descriptions of buboes) occurring in the area at the time being scant.

Influenza hit the Kingdom of Portugal at the same time as it spread throughout Spain, with an impact that spread across the Atlantic Ocean. The kingdom had just suffered food shortages due to 1556-57's poor harvest,[64] which would have exacerbated the effects of the flu on hungry patients. A violent storm had just hit Portugal and severely damaged the Palace of Enxobregas, and in following with attributing outbreaks of influenza to the weather Portuguese historians like Ignácio Barbosa-Machado attributed the epidemic in the kingdom to the storm with little opposition. Barbosa-Machado referred to 1557 as the "anno de catarro."[65]

The Americas

There are records of the New World eventually being reached by the flu in 1557, brought to the Spanish and Portuguese Empires by sailors from Europe.[21] Influenza arrived in Central America in 1557,[66] likely aboard Spanish ships sailing to New Spain. During that year there were epidemics of flu recorded in the south Atlantic states, Gulf area, and Southwest.[67] The Native American Cherokee appear to have been affected during this wave,[68] and it may have spread along newly established trade routes between Spanish colonies in the New World.

The flu also reached South America. Anthropologist Henry F. Dobyns described a 1557 epidemic of influenza in Ecuador in which European and Native populations were both left sick with severe coughing.[69] In Colonial Brazil, Portuguese missionaries did not take breaks from religious activities when they became sick.[70] Missionaries like the Society of Jesus in Brazil founder Manuel da Nóbrega continued to preach, host mass, and baptize converts in the New World even when symptomatic with contagious illnesses like influenza.[70] As a result, flu would have quickly spread through Portuguese colonies due to mandatory church attendance. In 1559 the flu struck colonial Brazil with a wave of illness recorded along the coastal state of Bahia:[71] That February, the region of Espírito Santo was struck by an outbreak of lung infections, dysentery, and "fevers that they say immediately attacked the hearts, and which quickly struck them down." Populations of natives attempted to flee the infection afflicting their communities, spreading influenza northward.[71] European missionaries suspected such severe epidemics among the native populations to be a form of divine punishment,[70] and referred to the outbreaks of pleurisy and dysentery among the natives in Bahia to be "the sword of God's wrath." Missionaries like Francisco Pires took some pity on the sick children of natives, whom they often regarded as innocent, and frequently baptized them during epidemics in the belief they'd "saved" their souls. Baptism rates in native communities were deeply connected with outbreaks of disease,[70] and missionary policies of conducting religious activities while sick likely helped spread the flu.

Africa

.png.webp)

Influenza attacked Africa through the Ottoman Empire, which by 1557 was expanding its territories in the northern and eastern parts of the continent. Egypt, which had been conquered by the Ottoman Empire around 40 years prior, became an access point for influenza to travel south through the Red Sea along shipping routes. The pandemic's most memorable effects on the Ottoman army in Africa are recorded as part of the 1559 wave.

Abyssinian Empire and Habesh Eyalet

The Kingdom of Portugal had supported the Abyssinian (Ethiopian) Empire in their war against the Ottoman expansion of the Habesh Eyalet and sent aid to their emperor, including a team with Andrés de Oviedo in 1557 who recorded the events.[72] In 1559 the Ottoman Empire struggled with a severe wave of influenza: After the deaths of Emperor Gelawdewos and most of the Portuguese attaché in battle, the flu killed thousands of the Ottoman army's troops occupying the port city of Massawa.[73][72] Massawa was claimed by the Ottomans from Medri Bahri during their conquest of Habesh in 1557, but the pandemic's 1559 wave challenged their army's hold onto territory around the city after flu cut down a large number of the Ottoman forces.[73][72] Because of the epidemic Ottoman soldiers were soon recalled back to the ports, even though the emperor had been slain, and shortly afterwards Gelawdewos's brother Menas ascended to the Abyssinian throne and converted from Islam to Christianity.[72]

Medicine and treatments

Most physicians of the time subscribed to the theory of humorism, and believed the cosmos or climate directly affected the health of entire communities. Physicians treating the flu often used treatments called coctions to remove excess humors they believed to be causing illness.[58] Dr. Thomas Short described treatments for the 1557 influenza as having included gargling "rose water, quinces, mulberries, and sealed earth." "Gentle bleeding" was used on the first day of the infection only,[74] as frequently used medical techniques like bloodletting and purgation were often fatal for influenza.[34] In Urbino, "diet and good governance" were recognized as common ways sufferers managed their illness.[23]

Identification as influenza

The 1557 pandemic's nature as a worldwide, highly-contagious respiratory disease with fast onset of flu-like symptoms has led many physicians, from medical historians like Charles Creighton to modern epidemiologists, to consider the causative disease as influenza.[1] "Well documented descriptions from medical observers"[1] who witnessed the effects of the pandemic as it spread through populations have been reviewed by numerous medical historians in the centuries since. Contemporary physicians to the 1557 flu, like Ingrassia, Valleriola, Dodoens, and Mercado, described symptoms like severe coughing, fever, myalgia, and pneumonia that all occurred within a short period of time and led to death in days if a case was to be fatal.[50][24][58] Infections became so widespread in countries that influences like the weather, stars, and mass poisoning were blamed by observers for the outbreaks, a reoccurring pattern in influenza epidemics that has contributed to the disease's name. Prior to greater research being conducted into influenza in the 19th century, some medical historians considered the descriptions of epidemic "angina" from 1557 to be scarlet fever, whooping cough, and diphtheria. But the most striking features of scarlet fever and diphtheria, like rashes or pseudomembranes, remain unmentioned by any of the 1557 pandemic's observers and the first recognized whooping cough epidemic is a localized outbreak in Paris from 1578.[75] These illnesses can resemble the flu in their early stages but pandemic influenza is distinguished by its fast-moving, unrestricted epidemics of severe respiratory disease affecting all ages with widespread infections and mortalities.

References

- Morens, David M; North, Michael; Taubenberger, Jeffery K (2010-12-04). "Eyewitness accounts of the 1510 influenza pandemic in Europe". Lancet. 376 (9756): 1894–1895. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(10)62204-0. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 3180818. PMID 21155080.

- Creighton, Charles (1891). A History of Epidemics in Britain - The type of sickness in 1558. Cambridge, England: The University Press. pp. 403–407. Archived from the original on 2022-10-07. Retrieved 2023-03-18.

- Eichel, Otto R. (December 1922). "The Long-Time Cycles of Pandemic Influenza". Journal of the American Statistical Association. Taylor & Francis. 18 (140): 451. doi:10.1080/01621459.1922.10502488. JSTOR 2276917.

- Alibrandi, Rosemarie (2018). "When early modern Europe caught the flu. A scientific account of pandemic influenza in sixteenth century Sicily". Medicina Historica. 2: 19–26.

- Taubenberger, J.K.; Morens, D.M. (April 2009). "Pandemic influenza – including a risk assessment of H5N1". Revue Scientifique et Technique (International Office of Epizootics). 28 (1): 187–202. doi:10.20506/rst.28.1.1879. ISSN 0253-1933. PMC 2720801. PMID 19618626.

- Creighton, Charles (1894). A History of Epidemics in Britain: From the extinction of plague to the present time. Cambridge, England: Oxford University Press. pp. 307–308.

- Rappaport, Steve (2002-04-04). Worlds Within Worlds: Structures of Life in Sixteenth-Century London. Cambridge University Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-521-89221-6.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Forum on Microbial Threats; Knobler, Stacey L.; Mack, Alison; Mahmoud, Adel; Lemon, Stanley M. (2005). The Story of Influenza. National Academies Press (US). Archived from the original on 2020-12-23. Retrieved 2020-05-16.

- The American Journal of Obstetrics and Diseases of Women and Children. New York: W. Wood & Company. 1919. p. 231. Archived from the original on 2021-09-11. Retrieved 2020-05-16.

- Pierson, A. L.; Flint, J. B.; Bartlett, E. (1834). The Medical Magazine. Boston: Allan & Ticknor. p. 92.

- Thompson, Theophilus (1852). Annals of Influenza Or Epidemic Catarrhal Fever in Great Britain from 1510 to 1837. Sydenham Society. p. 101. Archived from the original on 2021-02-25. Retrieved 2020-05-28.

- Lal, Kishori Saran (1973). Growth of Muslim Population in Medieval India, A.D. 1000-1800. Research [Publications in Social Sciences]. p. 51.

- SCHWEICH, Heinrich; HECKER, Justus Friedrich Carl (1836). Die Influenza. Ein historischer und ätiologischer Versuch ... Mit einer Vorrede von ... J. F. C. Hecker (in German). pp. 59–60.

- Hopkirk, Arthur F. (1914). Influenza: Its History, Nature, Cause, and Treatment. New York: Walter Scott Publishing Company. p. 31.

- Dehner, George (2012). Influenza: A Century of Science and Public Health Response. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 30. ISBN 9780822977858.

- A System of practical medicine v. 1, 1885. Philadelphia: Lea Bros. & Company. 1885. p. 854.

- Immerman, H.; von Jurgenson, Th.; Liebermeister, C.; Lenhartz, H.; Sticker, G. (1902). Moore, John (ed.). Encyclopedia of Practical Medicine. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders. p. 543.

- Webster, Noah (1800). A Brief History of Epidemic and Pestilential Diseases: With the Principal Phenomena of the Physical World, which Precede and Accompany Them, and Observations Deduced from the Facts Stated ... London: G.G. and J. Robinson, Paternoster-Row. p. 131.

- Ozanam, Jean Antoine François (1835). Historie médicale générale et particulière des maladies épidémiques, contagieuses et épizootiques, qui ont régné en Europe depuis les temps les plus reculés jusqu'a nos jours (in French). Paris: Chez tous les libraires pour la médecine. p. 186. Archived from the original on 2021-09-11. Retrieved 2020-05-28.

- Journal des connaissances médico-chirurgicales: 1837, Sém. 2 (in French). Bureau du Journal. 1837. p. 95.

- Parkin, John (1880). Epidemiology; or, The remote cause of epidemic diseases in the animal and in the vegetable creation. London: J. and A. Churchill. p. 36. Archived from the original on 2021-09-11. Retrieved 2020-03-24.

- Finkler, Ditmar (1898). "Influenza". Twentieth Century Practice - an International Encyclopedia of Modern Medical Science by Leading Authorities of Europe and America. William Wood and Company. 15: 12–13 – via Google Books.

- Corradi, Alfonso (5 June 1879). "La Enfermità di Toquato Tasso". Memorie del Reale Istituto Lombardo di Scienze e Lettere: Classe di Scienze Matematiche e Naturali (in Italian). TIP. BERNARDONI DI C. REBESCHINI E. C. 15: 331 – via Google Books.

- Adelon, Nicolas Philibert (1836). "Grippe (Histoire)". Dictionnaire de Médecine, Ou, Répertoire Général des Sciences Médicales Considérées Sous le Rapport Théorique et Pratique. 34 (1): 321. doi:10.3917/tf.131.0101. ISSN 0250-4952.

- Ladurie, Emmanuel Le Roy (1998-06-06). The Beggar and the Professor: A Sixteenth-Century Family Saga. Translated by Goldhammer, Arthur. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 321. ISBN 978-0-226-47324-6.

- Dictionnaire encyclopédique des sciences médicales (in French). Paris: Asselin. 1877. p. 332. Archived from the original on 2021-09-09. Retrieved 2020-11-04.

- Delorme, Raige (1837). "GRIPPE - IV. Histoire et Literature". Encyclographie des Sciences Médicales. Répertoire Général de Ces Sciences, Au XIXe Siècle. Brussels, Belgium: Établissement Encyclographique. 13: 258–259. Archived from the original on 2021-09-11. Retrieved 2020-05-28 – via Google Books.

- Brouardel, Paul; Agustin, Gilbert; Girode, Joseph (1895). Traité de médecine et de thérapeutique (in French). Paris: B. Ballière et Fils. p. 363.

- Wood, T.F.C. (1844). The Epidemics of the Middle Ages. London: G. Woodfall and Von. pp. 221–222.

- Cayla, Jean Mament (1839). Histoire de la ville de Toulouse depuis sa fondation jusqu'à nos jours, publiée sous la direction de M. J. M. Cayla et Perrin-Paviot. Ornée de douze gravures, etc (in French). Toulouse. p. 481. Archived from the original on 2021-09-11. Retrieved 2020-04-29.

- Deschambre, A. (1873). Dictionnaire encyclopédique des sciences médicales: Cas - Cép (in French). Masson. p. 241.

- Nothnagel, Hermann (1905). Nothnagel's Encyclopedia of practical medicine. v. 10, 1910. Philadelphia and London: W.B. Saunders & Company. p. 602.

- Bloss, Jas. R. (July 1920). "Influenza - Past and Present". West Virginia Medical Journal. 15: 287–288.

- Allbutt, M.D., Clifford (1907). Influenza. p. 105.

- "The Fall of Calais | History Today". www.historytoday.com. Archived from the original on 2021-06-29. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

- Loades, David (2006-08-23). Elizabeth I: A Life. London, UK: A&C Black. p. 121. ISBN 978-1-85285-520-8.

- Bucholz, Robert; Key, Newton (2019-12-31). Early Modern England 1485-1714: A Narrative History. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. p. 121. ISBN 978-1-118-53222-5.

- Zell, Michael (2000). Early Modern Kent, 1540-1640. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell & Brewer. p. 232. ISBN 978-0-85115-585-2.

- Arman, Steve; Bird, Simon; Wilkinson, Malcolm (2002). Reformation and Rebellion 1485-1750. Halley Court, Jordan Hill, Oxford: Heinemann. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-435-32303-5.

- Thompson, Theophilus (1852). Annals of Influenza Or Epidemic Catarrhal Fever in Great Britain from 1510 to 1837. Sydenham Society. p. 8.

- Starky, David (2002). "Edward and Mary: The Unknown Tudors". Youtube. Event occurs at 46:20-46:25. Archived from the original on 2020-06-18. Retrieved 2020-04-17.

- Nix, Elizabeth. "8 Things You Might Not Know about Mary I". HISTORY. Archived from the original on 2021-08-18. Retrieved 2020-05-30.

- Stow, John (1575). A Summarie of the Chronicles of England, from the first coming of Brute into this land, unto this present yeare of Christ 1575 ... Corrected and enlarged, etc. B.L. Richard Cottle and Henry Binneman. p. 501. Archived from the original on 2021-09-11. Retrieved 2021-01-12.

- DOBYNS, HENRY F. (1963). "An Outline of Andean Epidemic History to 1720". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 37 (6): 493–515. ISSN 0007-5140. JSTOR 44446986. PMID 14074186.

- Mémorial de Chronologie, d'Histoire Industrielle, d'Èconomie Politique, de Biographie, etc (in French). Paris: Chez Verdière, Libraire. 1830. p. 863.

- Brady, Thomas Allan; Oberman, Heiko Augustinus; Tracy, James D. (1993-12-31). Structures and Assertions. Leiden, The Netherlands: BRILL. p. 403. ISBN 978-90-04-09760-5.

- Bray, R. S. (2004-06-15). Armies of Pestilence: The Impact of Disease on History. Cambridge, England: ISD LLC. p. 196. ISBN 978-0-7188-4816-3.

- Coburn, H. (1843). Letters of Mary, Queen of Scots: Now First Published from the Originals, Collected from Various Sources, Private as Well as Public, with an Historical Introduction and Notes. H. Colburn. p. 349. Archived from the original on 2021-09-11. Retrieved 2020-05-21.

- Colin, Léon (1879). Traité des maladies épidémiques: origine, évolution, prophylaxie (in French). Paris: B. Ballière et Fills. p. 496.

- Hillier, M.D, Thomas (January 29, 1859). "On Diphterite". The Medical Times and Gazette, A Journal of Medical Science, Literature, Criticism, and News. London. 18: 107. Archived from the original on September 11, 2021. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- Twentieth century practice. New York: Sampson Low, Marston. 1898. p. 13.

- Torfs, Louis (1859). Fastes des calamites publiques survenues dans les Pays-Bas et particulierement en Belgique depuis les temps les plus recules jusqu'a nos jours, Epidemies; famines; inondations (in French). Paris: Libraire de P. Lenthielleux. p. 188. Archived from the original on 2021-09-11. Retrieved 2020-05-31.

- The Dublin Journal of Medical Science. Dublin: Fannin & Company. 1880. p. 98. Archived from the original on 2021-09-11. Retrieved 2020-06-12.

- Hart, Ernest, ed. (1880). British Medical Journal. London: British Medical Association. p. 159.

- "Influenza in America During the 16th Century". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 8: 297. 1940.

- Vaughan, M.D., Warren T. (July 1921). "Influenza - An Epidemiologic Study". The American Journal of Hygiene. 1: 19. ISBN 9780598840387.

- Allbutt, M.D., Clifford (1907). Influenza. p. 128.

- Culbertson, M.D., J. C., ed. (1890). The Cincinnati Lancet-clinic. Cincinnati: J.C. Culbertson. p. 52. Archived from the original on 2021-09-11. Retrieved 2020-03-25.

- Kamen, Henry (2014-03-26). Spain, 1469-1714: A Society of Conflict. Routledge. p. 113. ISBN 978-1-317-75500-5.

- Webster, Noah (1800). A Brief History of Epidemic and Pestilential Diseases: With the Principal Phenomena of the Physical World, which Precede and Accompany Them, and Observations Deduced from the Facts Stated ... London: G.G. and J. Robinson, Paternoster-Row. p. 421. Archived from the original on 2021-09-11. Retrieved 2020-04-26.

- Christian, William A. (1981). Local Religion in Sixteenth-century Spain. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-691-00827-1.

- "Las epidemias de Valencia y la Virgen de los Desamparados". El Periódico de Aquí (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2020-05-24. Retrieved 2020-05-31.

- Vincent, Bernard (1969). "Les pestes dans le royaume de Grenade aux XVIe et XVIIe siècles". Annales. 24 (6): 1511–1513. doi:10.3406/ahess.1969.422184. S2CID 162228482. Archived from the original on 2021-09-11. Retrieved 2020-05-31.

- Abreu-Ferreira, Darlene (2016-03-09). Women, Crime, and Forgiveness in Early Modern Portugal. Abingdon: Routledge. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-134-77758-7.

- Annaes das sciencias e lettras (in Brazilian Portuguese). Lisbon: Typographia da Academia. 1857. p. 302. Archived from the original on 2021-09-11. Retrieved 2020-06-07.

- University, Harvard (1984-12-06). The Cambridge History of Latin America. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Cambridge University Press. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-521-23223-4.

- Barrett, Carole A. (2003). American Indian History: Aboriginal action plan-Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe. Salem Press. p. 127. ISBN 978-1-58765-068-0.

- Thornton, Russell (1990). The Cherokees: A Population History. University of Nebraska at Lincoln: U of Nebraska Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-8032-9410-3.

- Pease, Franklin; Damas (1999). Historia general de América Latina: El primer contacto y la formación de nuevas sociedades (in Spanish). Paris, France: UNESCO. p. 311. ISBN 978-92-3-303151-7.

- Metcalf, Alida C. (2013-05-01). Go-betweens and the Colonization of Brazil: 1500–1600. University of Texas Press. pp. 149–150. ISBN 978-0-292-74860-6.

- Cook, Noble David (1998-02-13). Born to Die: Disease and New World Conquest, 1492-1650. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 112–114. ISBN 978-0-521-62730-6.

- Whiteway, R. S. (2017-05-15). The Portuguese Expedition to Abyssinia in 1541-1543, as narrated by Castanhoso: With Some Contemporary Letters, the Short Account of Bermudez, and Certain Extracts from Correa. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-01974-9.

- Welch, Sidney R. (1949). South Africa Under John III, 1521-1557. Juta. p. 244.

- F. Flick, M.D., Lawrence (1892). "The Treatment of Epidemic Influenza by Rest and Stimulants". Proceedings of the Philadelphia County Medical Society. 13: 40 – via Google Books.

- Whooping Cough: Essential Facts Concerning Whooping Cough, Its Prevention and Treatment with Appropriate Vaccines. Indianapolis, Indiana: Eli Lilly & Company. 1920. p. 3.