Second plague pandemic

The second plague pandemic was a major series of epidemics of plague that started with the Black Death, which reached Europe in 1346 and killed up to half of the population of Eurasia in the next four years. Although the plague died out in most places, it became endemic and recurred regularly. A series of major epidemics occurred in the late 17th-century, and the disease recurred in some places until the late 18th-century or the early-19th century.[1][2] After this, a new strain of the bacterium gave rise to the third plague pandemic, which started in Asia around the mid-19th century.[3][4]

Plague is caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, which exists in parasitic fleas of several species in the wild and of rats in human society. In an outbreak, it may kill all of its immediate hosts and thus die out, but it can remain active in other hosts that it does not kill, thereby causing a new outbreak years or decades later. The bacterium has several means of transmission and infection, including through fleas on rats carried on ships or vehicles, fleas hidden in grain, and via blood and sputum directly between humans.

Overview

There have been three major outbreaks of plague. The Plague of Justinian in the 6th and 7th centuries is the first known attack on record, and marks the first firmly recorded pattern of plague. From historical descriptions, as much as 40% of the population of Constantinople died from the plague. Modern estimates suggest that half of Europe's population died as a result of this first plague pandemic before it disappeared in the 700s.[5] After 750, plague did not appear again in Europe until the Black Death of the 14th-century.[6]

The second pandemic's origins are disputed; originating either in Central Asia or Crimea,[7][8][9][10][11][12][13] and appearing in Crimea by 1347. It may have reduced world population from an estimated 450 million to 350–375 million by the year 1400.[14] A study published in the journal Nature in June 2022 found evidence for Yersinia pestis in the teeth of early plague victims in the Tian Shan mountains, now north Kyrgyzstan, indicating a likely origin of that iteration of the plague.[15]

The plague returned at intervals with varying virulence and mortality until the early 19th-century. In England, for example, the plague returned between 1360 and 1363, killing 20% of Londoners, and then again in 1369, killing 10–15%.[16]

In the 16th-century, the plague hit San Cristóbal de La Laguna in the Canary Islands between 1582 and 1583.[17]

In the 17th-century, there were a series of European "great plague" outbreaks: the Great Plague of Seville between 1647 and 1652, the Great Plague of London between 1665 and 1666,[18] and the Great Plague of Vienna in 1679. The great plague of northern China arose in Shanxi in 1633 and arrived at Beijing in 1641, contributing to the downfall of the Ming Dynasty in 1644.

In the 18th-century, there was the Great Plague of Marseille, which took place between 1720 and 1722;[19] the Great Plague of 1738, which occurred in Eastern Europe between 1738 and 1740; and the Russian plague of 1770–1772, which took place in Central Russia, and particularly affected Moscow. However, the plague in its virulent form seemed to gradually disappear from Europe, though lingering in Egypt and the Middle East.

By the early 19th-century, the threat of plague had diminished, though it was quickly replaced by the spread of another deadly, infectious disease in the first cholera pandemic, beginning in 1817; the first of several cholera pandemics to sweep through Asia and Europe during the 19th and 20th centuries.[20]

The third plague pandemic hit China in the 1890s and devastated India. While it was largely contained in the East, it became endemic in the western United States, where sporadic outbreaks of plague continue to occur.[11]

Black Death

Arab historians Ibn Al-Wardi and Almaqrizi believed the Black Death originated in Mongolia, and Chinese records show a huge outbreak in Mongolia in the early 1330s.[21]

In recent years, more research has emerged that shows the Black Death most likely originated on the northwestern shores of the Caspian Sea,[22] and may not even have reached India and China, as research on the Delhi Sultanate and the Yuan Dynasty showed no evidence of any serious epidemic in 14th-century India and no specific evidence of plague in 14th-century China.[9]

There were large epidemics in China in 1331 and between 1351 and 1354 in the provinces of Hebei, Shanxi, and others, which are considered to have killed between 50% and 90% of the local populations, with numbers running into the tens of millions. However, there is no proof currently that these were caused by plague, though there are indications for the second set of epidemics.[23] Europe was initially protected by a hiatus in the Silk Road.

Plague was reportedly first introduced to Europe via Genoese traders from their port city of Kaffa in Crimea in 1347. During a protracted siege of the city, between 1345 and 1346, the Mongol Golden Horde army of Jani Beg, whose mainly Tatar troops were suffering from the disease, catapulted infected corpses over the city walls of Kaffa to infect the inhabitants,[24] though it is more likely that infected rats travelling across the siege lines spread the epidemic to the inhabitants.[25][26] As the disease took hold, Genoese traders fled across the Black Sea to Constantinople, where the disease first arrived in Europe in summer 1347.[27] The epidemic there killed the 13-year-old son of the Byzantine emperor, John VI Kantakouzenos, who wrote a description of the disease modelled on Thucydides' account of the 5th-century BCE Plague of Athens, but noting the spread of the Black Death by ship between maritime cities.[27] Nicephorus Gregoras also described in writing to Demetrios Kydones the rising death toll, the futility of medicine against it, and the panic of the citizens.[27]

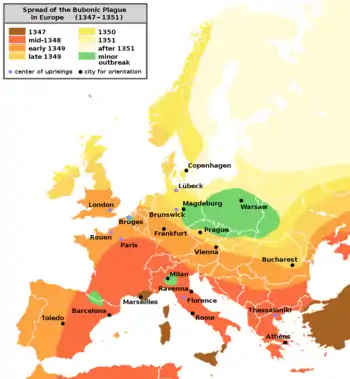

It arrived at Genoa and Venice in January 1348, while simultaneously spreading through Asia Minor and into Egypt. The bubonic form was described graphically in Florence in The Decameron and Guy de Chauliac also described the pneumonic form at Avignon. It rapidly spread to France and Spain and, by 1349, was in England. In 1350, it was afflicting Eastern Europe and had reached the centre of Russia by 1351.

The 14th-century eruption of the Black Death had a drastic effect on Europe's population, irrevocably changing its social structures, and resulted in the widespread persecution of minorities such as Jews, foreigners, beggars, and lepers. The uncertainty of daily survival has been seen as creating a general mood of morbidity, influencing people to "live for the moment", as illustrated by Giovanni Boccaccio in The Decameron (1353).[28] Petrarch, noting the unparalleled and unbelievable extremity of the disease's effects, wrote that "happy posterity, who will not experience such abysmal woe ... will look upon our testimony as a fable".[29][30]

Recurrences

The second pandemic spread throughout Eurasia and the Mediterranean Basin. The plague repeatedly returned to haunt Europe and the Mediterranean Basin throughout the 16th to 17th centuries.[31] The plague ravaged much of the Islamic world.[32] Plague was present in at least one location in the Islamic world virtually every year between 1500 and 1850.[33] According to Jean-Noel Biraben, plague was present somewhere in Europe in every year between 1346 and 1671.[34] According to Ellen Schiferl, between 1400 and 1600, there was a plague epidemic recorded in at least one part of Europe for every year, except 1445.[35][30]

Byzantine Empire and Ottoman Empire

In the Byzantine Empire, the 1347 Black Death outbreak in Constantinople lasted a year, but plague recurred ten times before 1400.[27] Plague was repeatedly reintroduced to the city because of its strategic location between the Mediterranean Sea and the Black Sea, and between Europe and Asia, as well as its position as the imperial capital.[27]

Constantinople retained its imperial status at the centre of the Ottoman Empire after the Fall of Constantinople to Mehmed the Conqueror in 1453.[27] Approximately 1–2% of the city's population died annually of plague.[27] Especially severe episodes were recorded by the Ottoman historians Mustafa Âlî and Hora Saadettin between 1491 and 1503, with 1491 through 1493 being the most afflicted years.[27] Plague returned in 1511 until 1514 and, after 1520, was endemic in the city until 1529.[27] Plague was endemic in Constantinople again between 1533 and 1549, 1552 and 1567, and for most of the remaining 16th-century.[27]

In the 17th-century, plague epidemics within Constantinople were noted in the following years: 1603, 1611 to 1613, 1647 to 1649, 1653 to 1656, 1659 to 1688, 1671 to 1680, 1685 to 1695, and 1697 to 1701.

In the 18th-century, there were 64 years in which plague broke out in the capital, and a further 30 plague years which occurred in the first half of the 19th-century.[27] Of these later 94 plague epidemics in Constantinople between 1700 and 1850, six of them—occurring in 1705, 1726, 1751, 1778, 1812, and 1836—are estimated to have killed more than 5% of the population, whereas 83 of the epidemics killed 1% or fewer.[27]

Plague repeatedly struck the cities of North Africa. Between 1620 and 1621, Algiers lost 30,000–50,000 people to it, with outbreaks returning in 1654 to 1657, 1665, 1691, and 1740 to 1742.[36]

Plague remained a major event in Ottoman society until the second quarter of the 19th-century. Between 1701 and 1750, thirty-seven both large scale and smaller epidemics were recorded in Constantinople, with a further thirty-one occurring between 1751 and 1800.[37] The Great Plague of 1738 affected Ottoman territory in the Balkans, lasting until 1740.

Baghdad suffered severely from visitations of the plague, with outbreaks reducing the population to one third of its size by 1781.[38]

One of the last epidemics to strike the Balkans during the second plague pandemic was Caragea's plague, between 1813 and 1814.[16]

Swiss explorer Johann Ludwig Burckhardt witnessed the plague epidemics that ravaged Hejaz and Egypt between 1812 and 1816. He wrote: "In five or six days after my arrival [in Yanbu] the mortality increased; forty or fifty persons died in a day, which, in a population of five or six thousand, was a terrible mortality."[39]

Holy Roman Empire

Although regular outbreaks of disease were common for decades prior to 1618, the Thirty Years' War (1618–48) greatly accelerated their spread. Based on local records, military action accounted for less than 3% of civilian deaths; the major causes were starvation (12%) and bubonic plague (64%).[40] The modern consensus is the population of the Holy Roman Empire declined from 18 to 20 million in 1600 to 11 to 13 million in 1650, and did not regain pre-war levels until 1750.[41]

The Great Plague of Vienna struck Vienna, the dynastic seat of the Holy Roman Empire, in 1679,[16] killing an estimated 76,000 people. Emperor Leopold I fled the city upon the outbreak, but vowed to erect a Marian column in thanksgiving, if the plague would end. Vienna's Plague Column, located on the Graben, was commissioned in 1683 and inaugurated in 1694.

Italian Peninsula

- See also Black Death in Italy

By 1357, the plague had returned to Venice and, from 1361 to 1363, the rest of Italy experienced the first recurrence of the pandemic.[30] Pisa, Pistoia, and Florence in Tuscany were especially badly affected; there pesta secunda, 'second pestilence' killed a fifth of the population.[30] In the pesta tertia, 'third pestilence' of 1369 to 1371, 10–15% died.[30]

Survivors were aware that the Black Death of 1347 to 1351 was not a unique event and that life was now "far more frightening and precarious than before".[30] The Italian peninsula was struck with an outbreak of plague in 68% of the years between 1348 and 1600.[30] There were 22 outbreaks of plague in Venice between 1361 and 1528.[42] Petrarch, writing to Giovanni Boccaccio in September 1363, lamented that while the Black Death's arrival in Italy in 1348 had been mourned as an unprecedented disaster, "Now we realize that it is only the beginning of our mourning, for since then this evil force, unequalled and unheard of in human annals through the centuries, has never ceased, striking everywhere on all sides, on the left and right, like a skilled warrior."[43][30]

In the Jubilee Year of 1400, announced by Pope Boniface IX, one of the most severe occurrences of plague was exacerbated by the many pilgrims making their way to and from Rome; in the city itself 600–800 died daily.[30] As recorded by the undertakers' records in Florence, at least 10,406 people died; the total death toll was estimated at twice that figure by 15th century chronicler Giovanni Morelli.[30] Half of the population of Pistoia and its hinterland were killed that year.[30]

Another outbreak occurred in Padua in 1405 and claimed 18,000 lives.[30] In the plague epidemic of 1449 to 1452, 30,000 Milanese died in 1451 alone.[30]

A particularly deadly plague struck Italy between 1478 and 1482.[30] The territories of the Republic of Venice saw 300,000 dead in the epidemic's eight-year course.[30] Luca Landucci wrote in 1478 that the citizens of Florence "were in a sorry plight. They lived in dread, and no one had any heart to work. The poor creatures could not procure silk or wool ... so that all classes suffered."[30] In addition to plague, Florence was suffering both from excommunication leading to war with the Papal States and from the political strife following the Pazzi conspiracy.[30]

In 1479, the plague broke out in Rome; Bartolomeo Platina, the head of the Vatican Library was killed, and Pope Sixtus IV fled the city and was absent for more than a year.[30] Federico da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino also died.[30]

Following the Sack of Rome in 1527 by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, plague broke out in both Rome and Florence. The plague emerged in Rome and killed 30,000 Florentines—a quarter of the city's inhabitants.[30] The Description of the Plague at Florence in the Year 1527, by Lorenzo di Filippo Strozzi, records this plague in detail; copied out by Niccolò Machiavelli with annotations by Strozzi.[30] He wrote:

Our pitiful Florence now looks like nothing but a town which has been stormed by infidels and then forsaken. One part of the inhabitants, ... have retired to distant country houses, one part is dead, and yet another part is dying. Thus the present is torment, the future menace, so we contend with death and only live in fear and trembling. The clean, fine streets which formerly teemed with rich and noble citizens are now stinking and dirty; crowds of beggars drag themselves through them with anxious groans and only with difficulty and dread can one pass them. Shops and inns are closed, at the factories work has ceased, the law courts are empty, the laws are trampled on. Now one hears of some theft, now of some murder. The squares, the market places on which citizens used frequently to assemble, have now been converted into graves and into the resort of the wicked rabble. ... If by chance relations meet, a brother, a sister, a husband, a wife, they carefully avoid each other. What further words are needed? Fathers and mothers avoid their own children and forsake them. ... A few provision stores are still open, where bread is distributed, but where in the crush plague boils are also spread. Instead of conversation ... one hears now only pitiful, mournful tidings – such a one is dead, such a one is sick, such a one has fled, such a one is interned in his house, such a one is in hospital, such a one has nurses, another is without aid, such like news which by imagination alone would suffice to make Aesculapius sick.

— Lorenzo di Filippo Strozzi, Description of the Plague at Florence in the Year 1527

Further plague epidemics accompanied the Siege of Florence in 1529; there, religious buildings became hospitals and 600 temporary structures were built to house the infected without the city walls.[30]

After 1530, political strife calmed and warfare in Italy became less frequent. Subsequently, plague outbreaks became more rare, affecting only individual cities or regions,[30] but were particularly severe.[30] In the forty-three years between 1533 and 1575, there were eighteen epidemics of plague.[30] The especially damaging Italian plague of 1575 to 1578 travelled both north and southwards through the peninsula from either end; the death toll was particularly high.[30] By official reckoning, Milan lost 17,329 to plague in 1576, while Brescia recorded 17,396 killed in a town that did not exceed 46,000 total inhabitants.[30] Venice, meanwhile, saw between a quarter and a third of its population die of plague in the epidemic of 1576 to 1577 with 50,000 deaths.[44][30]

In the first half of the 17th century, a plague claimed some 1.7 million victims in Italy, or about 14% of the population.[45]

The Great Plague of Milan (1629-1631) was possibly the most disastrous of the century: the city of Milan lost half its population of about 100,000, while Venice was as afflicted as in its severe 1553 to 1556 outbreak.[30]

The Italian Plague of 1656 to 1657 was the last major catastrophic plague in Italy, with the Naples Plague the most severe.[30] In 1656, the plague killed about half of Naples's 300,000 inhabitants.[46]

Messina saw the last epidemic in Italy, in 1742 to 1744.[30] The final recorded incidence of plague in Italy was in 1815 to 1816, when plague broke out in Noja, a town near Bari.[30]

Northern Europe

Over 60% of Norway's population died from 1348 to 1350.[47] The last plague outbreak ravaged Oslo in 1654.[48]

In Russia, where the disease hit somewhere once every five or six years from 1350 to 1490.[49] In 1654, the Russian plague killed about 700,000 inhabitants.[50][51]

In 1709–1713, a plague epidemic followed the Great Northern War (1700–1721), between Sweden and the Tsardom of Russia and its allies,[52] killing about 100,000 in Sweden,[53] and 300,000 in Prussia.[54] The plague killed two-thirds of the inhabitants of Helsinki,[55] and claimed a third of Stockholm's population.[56] This was the last plague in Scandinavia, but the Russian plague of 1770–1772 killed up to 100,000 people in Moscow.[57]

Eastern Europe

Great Plague of 1738 was a pandemic of plague lasting 1738–1740 and affecting areas in the modern nations of Romania, Hungary, Ukraine, Serbia, Croatia, and Austria.[16] The Russian plague epidemic of 1770-1772 killed as much as 100,000 people in Moscow alone, with thousands more dying in the surrounding countryside.[58]

France

In 1466, perhaps 40,000 people died of plague in Paris.[59] During the 16th and 17th centuries, plague visited Paris nearly once every three years, on average.[60] According to historian Geoffrey Parker, "France alone lost almost a million people to plague in the epidemic of 1628–31."[61] Western Europe's last major epidemic occurred in 1720 in Marseilles.[47]

Britain

Plague epidemics ravaged London in the 1563 London plague, in 1593, 1603, 1625, 1636, and 1665,[62] reducing its population by 10 to 30% during those years.[63] The 1665–66 Great Plague of London was the final major epidemic of the pandemic, with the last death of plague in the walled City of London recorded fourteen years later in 1679.

Low Countries

Over 10% of Amsterdam's population died in 1623–25, and again in 1635–36, 1655, and 1664.[64]

Iberia

More than 1.25 million deaths resulted from the extreme incidence of plague in 17th-century Spain.[65] The plague of 1649 probably reduced the population of Seville by half.[54]

Malta

Malta suffered from a number of plague outbreaks during the second pandemic between the mid-14th and early 19th centuries. The most severe outbreak was the epidemic of 1675–1676 which killed around 11,300 people,[66] followed by the epidemic of 1813–1814 and that of 1592–1593, which killed around 4,500 and 3,000 people respectively.[67][68]

Tenerife

The 1582 Tenerife plague epidemic (also 1582 San Cristóbal de La Laguna plague epidemic), was an outbreak of bubonic plague that occurred between 1582 and 1583 on the island of Tenerife, Spain. It is currently believed to have caused between 5,000 and 9,000 deaths on an island with fewer than 20,000 inhabitants at that time (between approximately 25-45% of the island's population).[69]

Major outbreaks

.jpg.webp)

.png.webp)

Disappearance

The 18th and 19th century outbreaks, though severe, marked the retreat of the pandemic from most of Europe (18th century), northern Africa, and the Near East (19th century).[84] The pandemic died out progressively across Europe. One documented case was in 17th century London, where the first proper demographer, John Graunt, failed by just five years to see the last recorded death from plague, which happened in 1679, 14 years after the Great Plague of London. The reasons it died out totally are not well understood.[85] It is tempting to think that the Great Fire of London the next year destroyed the hiding places of the rats in the roofs. There was not a single recorded plague death "within the walls" after 1666. However, by this time, the city had spread well beyond the walls, which contained most of the fire, and most plague cases happened beyond the limits of the fire. Likely more significant was the fact that all buildings after the fire were constructed of brick rather than wood and other flammable materials.

This pattern was broadly followed after major epidemics in northern Italy (1631), south and east Spain (1652), southern Italy and Genoa (1657), Paris (1668).

Appleby[86] considers six possible explanations:

- People developed immunity.

- Improvements in nutrition made people more resistant.

- Improvements in housing, urban sanitation and personal cleanliness reduced the number of rats and rat fleas.

- The dominant rat species changed. (The brown rat did not arrive in London until 1727.)

- Quarantine methods improved in the 17th century.

- Some rats developed immunity so fleas never left them in droves to humans, non-resistant rats were eliminated and this broke the cycle.

Synder suggests[87] that the replacement of the Black rat (Rattus rattus), which thrived among people and was frequently kept as a pet, by the more aggressive and prolific Norway or brown rat (Rattus norvegicus) was a major factor. The Brown rat, which arrived as an invasive species from the East, is skittish and avoids human contact, and their aggressive and asocial behavior made them less attractive to humans. As the Brown rat violently drove out the Black rat in country after country, becoming the dominant species in that ecological niche, rat-to-human contact declined, as did the opportunities for plague to pass from rat fleas to humans. One of the major demarcations for hot spots in the third plague pandemic was the places where the Black rat had yet to be replaced, such as Bombay (now Mumbai) in India. It has been suggested that evolutionary processes may have favored less virulent strains of the pathogen Yersinia pestis.[88]

In all probability, almost all of the existing hypotheses had some effect in bringing about the end of the pandemic, though the main cause may never be conclusively determined.The disappearance happened rather later in the Nordic and eastern European countries but there was a similar halt after major epidemics.

See also

References

Notes

- Spyrou, Maria A.; Keller, Marcel; Tukhbatova, Rezeda I.; Scheib, Christiana L.; Nelson, Elizabeth A.; Andrades Valtueña, Aida; Neumann, Gunnar U.; Walker, Don; Alterauge, Amelie; Carty, Niamh; Cessford, Craig (2019-10-02). "Phylogeography of the second plague pandemic revealed through analysis of historical Yersinia pestis genomes". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 4470. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10.4470S. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-12154-0. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 6775055. PMID 31578321.

- Guellil, Meriam; Kersten, Oliver; Namouchi, Amine; Luciani, Stefania; Marota, Isolina; Arcini, Caroline A.; Iregren, Elisabeth; Lindemann, Robert A.; Warfvinge, Gunnar; Bakanidze, Lela; Bitadze, Lia (2020-11-10). "A genomic and historical synthesis of plague in 18th century Eurasia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117 (45): 28328–28335. Bibcode:2020PNAS..11728328G. doi:10.1073/pnas.2009677117. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 7668095. PMID 33106412.

- "The History of Plague – Part 1. The Three Great Pandemics". jmvh.org. Retrieved 2021-01-15.

- Bramanti, Barbara; Dean, Katharine R.; Walløe, Lars; Chr. Stenseth, Nils (2019-04-24). "The Third Plague Pandemic in Europe". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 286 (1901). doi:10.1098/rspb.2018.2429. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 6501942. PMID 30991930.

- "Plague, Plague Information, Black Death Facts, News, Photos", National Geographic, retrieved 3 November 2008

- Hays 2005, p. 23.

- Hollingsworth, Julia (24 November 2019). "Black Death in China: A history of plagues, from ancient times to now". CNN. Archived from the original on 6 March 2020. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- Benedictow 2004, p. 50-51.

- Sussman, George D. (2011). "Was the Black Death in India and China?". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 85 (3): 319–355. doi:10.1353/bhm.2011.0054. JSTOR 44452010. PMID 22080795. S2CID 41772477.

- Bramanti et al. 2016, pp. 1–26.

- Wade 2010.

- "Black Death | Causes, Facts, and Consequences". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 9 July 2019. Retrieved 2020-03-01.

- Wade, Nicholas. "Black Death's Origins Traced to China". query.nytimes.com. Retrieved 2020-03-01.

- Historical Estimates of World Population, Census.gov, retrieved 27 December 2012

- Spyrou, Maria A.; Musralina, Lyazzat; Gnecchi Ruscone, Guido A.; Kocher, Arthur; Borbone, Pier-Giorgio; Khartanovich, Valeri I.; Buzhilova, Alexandra; Djansugurova, Leyla; Bos, Kirsten I.; Kühnert, Denise; Haak, Wolfgang (2022-06-15). "The source of the Black Death in fourteenth-century central Eurasia". Nature. 606 (7915): 718–724. Bibcode:2022Natur.606..718S. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04800-3. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 9217749. PMID 35705810. S2CID 249709693.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Las epidemias de la Historia: la peste en La Laguna (1582–1583)

- A list of National epidemics of plague in England 1348–1665, Urbanrim.org.uk, retrieved 3 November 2008

- Plague History Provence, – by Provence Beyond, Beyond.fr, retrieved 3 November 2008

- "Cholera's seven pandemics". CBC News. 2 December 2008.

- Sean Martin (2001). "Chapter One". Black Death. Harpenden, UK: Pocket Essentials. p. 14.

- Benedictow 2004, pp. 50–51.

- McNeill 1998.

- Wheelis 2002.

- Barras & Greub 2014. "In the Middle Ages, a famous although controversial example is offered by the siege of Caffa (now Feodossia in Ukraine/Crimea), a Genovese outpost on the Black Sea coast, by the Mongols. In 1346, the attacking army experienced an epidemic of bubonic plague. The Italian chronicler Gabriele de' Mussi, in his Istoria de Morbo sive Mortalitate quae fuit Anno Domini 1348, describes quite plausibly how the plague was transmitted by the Mongols by throwing diseased cadavers with catapults into the besieged city, and how ships transporting Genovese soldiers, fleas and rats fleeing from there brought it to the Mediterranean ports. Given the highly complex epidemiology of plague, this interpretation of the Black Death (which might have killed >25 million people in the following years throughout Europe) as stemming from a specific and localized origin of the Black Death remains controversial. Similarly, it remains doubtful whether the effect of throwing infected cadavers could have been the sole cause of the outburst of an epidemic in the besieged city."

- Byrne, Joseph Patrick (2012). "Caffa (Kaffa, Fyodosia), Ukraine". Encyclopedia of the Black Death. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-59884-253-1.

- Byrne, Joseph Patrick (2012). "Constantinople/Istanbul". Encyclopedia of the Black Death. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-59884-254-8. OCLC 769344478.

- "Boccaccio: The Decameron, 'Introduction'". Fordham.edu. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- Petrarch, Epistolae familiares IV.12.208

- White, Arthur (2014). "The Four Horsemen". Plague and Pleasure: The Renaissance World of Pius II. Washington D.C.: Catholic University of America Press. pp. 21–48. ISBN 978-0-8132-2681-1.

- Porter 2009, p. 25.

- The Islamic World to 1600: The Mongol Invasions (The Black Death), Ucalgary.ca, archived from the original on January 31, 2009, retrieved December 10, 2011

- Byrne 2008, p. 519.

- Hays 1998, p. 58.

- Schiferl, Ellen (1983). "Iconography of plague saints in fifteenth-century Italian painting". Fifteenth Century Studies. 6: 205–225.

- Davis 2003, p. 18.

- Université de Strasbourg. Institut de turcologie, Université de Strasbourg. Institut d'études turques, Association pour le développement des études turques. (1998), Turcica, Éditions Klincksieck, p. 198

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Issawi 1988, p. 99.

- Travels in Arabia; comprehending an account of those territories in Hedjaz which the Mohammedans regard as sacred by Burckhardt, John Lewis, 1784-1817 (1829). pp. 247–252.

- Outram, Quentin (2001). "The Socio-Economic Relations of Warfare and the Military Mortality Crises of the Thirty Years' War" (PDF). Medical History. 45 (2): 160–161. doi:10.1017/S0025727300067703. PMC 1044352. PMID 11373858.

- Parker, Geoffrey (2008). "Crisis and Catastrophe: The global crisis of the seventeenth century reconsidered". American Historical Review. 113 (4): 1058. doi:10.1086/ahr.113.4.1053.

- Brian Pullan (2006), Crisis And Change in the Venetian Economy in the Sixteenth And Seventeenth Centuries, Taylor & Francis Group, p. 151, ISBN 978-0-415-37700-3

- Petrarch, Seniles III.1.79–80

- Mary Lindemann (1999), Medicine and Society in Early Modern Europe, Cambridge University Press, p. 41, ISBN 978-0-521-42354-0

- Karl Julius Beloch, Bevölkerungsgeschichte Italiens, volume 3, pp. 359–360.

- Naples in the 1600s, Faculty.ed.umuc.edu, archived from the original on October 10, 2008, retrieved November 3, 2008

- Harald Aastorp (2004-08-01), Svartedauden enda verre enn antatt, Forskning.no, retrieved January 3, 2009

- Øivind Larsen, DNMS.NO : Michael: 2005 : 03/2005 : Book review: Black Death and hard facts, Dnms.no, retrieved November 3, 2008

- Byrne 2004, p. 62.

- Collins S. (1671) The Present State of Russia. Edited by Marshall T. Poe, 2008

- Медовиков П. Е. (1854) Историческое значение царствования Алексея Михайловича

- Kathy McDonough, Empire of Poland, Depts.washington.edu, archived from the original on October 11, 2008, retrieved November 3, 2008

- Alexander 1980, p. 21.

- Bray 2004, p. 72.

- Ruttopuisto – Plague Park, Tabblo.com, archived from the original on April 11, 2008, retrieved November 3, 2008

- Tony Griffiths (2009), Stockholm: A Cultural History, Oxford University Press, p. 9, ISBN 978-0-19-538638-7

- Melikishvili, Alexander (2006). "Genesis of the anti-plague system: the Tsarist period" (PDF). Critical Reviews in Microbiology. 36 (1): 19–31. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.204.1976. doi:10.1080/10408410500496763. PMID 16610335. S2CID 7420734. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 November 2009. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- Glatter, Kathryn A.; Finkelman, Paul (February 2021). "History of the Plague: An Ancient Pandemic for the Age of COVID-19". The American Journal of Medicine. 134 (2): 176–181. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.08.019. PMC 7513766. PMID 32979306.

- Shadwell, Hennessy & Payne 1911.

- Harding 2002, p. 25.

- Parker 2001, p. 7.

- Harding 2002, p. 24.

- "Plague in London: spatial and temporal aspects of mortality", J. A. I. Champion, Epidemic Disease in London, Centre for Metropolitan History Working Papers Series, No. 1 (1993).

- Geography, climate, population, economy, society Archived 2010-02-03 at the Wayback Machine. J.P.Sommerville.

- The Seventeenth-Century Decline, S.G. Payne, A History of Spain and Portugal

- Bartolomeo Dal Pozzo (1715). Historia della sacre religione militare di S. Giovanni gerosolimitano della di Malta. Albrizzi. p. 455.

- Brogini, Anne (2005). "Chapitre XI. l'Irrésistible ascension du commerce". Malta, border of Christianity (1530-1670). Bibliothèque des Écoles françaises d'Athènes et de Rome. Publications of the French School of Rome. pp. 565–615. ISBN 9782728307425.

- Attard, Eddie (9 June 2013). "Role of the Police in the plague of 1813". Times of Malta. Archived from the original on 12 March 2020.

- "Plague. The fourth horseman – Historic epidemics and their impact in Tenerife" (PDF) (in Spanish). p. 28. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- "The Bright Side of the Black Death". American Scientist. 2017-02-06. Retrieved 2021-01-16.

- Gottfried 1983, p. 131.

- Bray 2004, p. 71.

- "Plague. The fourth horseman – Historic epidemics and their impact in Tenerife" (PDF) (in Spanish). p. 28. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- Graunt 1759.

- Hays 2005, p. 103.

- Brook, Timothy (September 1999). The Confusions of Pleasure: Commerce and Culture in Ming China. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-22154-3.

- Ch'iu, Chung-lin. "The Epidemics in Ming Beijing and the Responses from the Empire's Public Health System".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Scasciamacchia, Silvia; Serrecchia, Luigina; Giangrossi, Luigi; Garofolo, Giuliano; Balestrucci, Antonio; Sammartino, Gilberto; Fasanella, Antonio (2012). "Plague Epidemic in the Kingdom of Naples, 1656–1658". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 18 (1): 186–188. doi:10.3201/eid1801.110597. PMC 3310102. PMID 22260781.

- Hashemi Shahraki, A.; Carniel, E.; Mostafavi, E. (2016). "Plague in Iran: its history and current status". Epidemiology and Health. 38: e2016033. doi:10.4178/epih.e2016033. PMC 5037359. PMID 27457063.

- Mikhail 2014, p. 43.

- Chase-Levenson, Alex (2020). The Yellow Flag: Quarantine and the British Mediterranean World, 1780–1860. Cambridge University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-108-48554-8. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- Ştefan Ionescu, Bucureștii în vremea fanarioţilor (Bucharest in the time of the Phanariotes), Editura Dacia, Cluj, 1974, pp. 287–293.

- https://www.e-epih.org/upload/pdf/epih-e2016033-AOP.pdf

- Hays 2005, p. 46.

- Spyrou, Maria A.; Tukhbatova, Rezeda I.; Feldman, Michal; Drath, Joanna; Kacki, Sacha; De Heredia, Julia Beltrán; Arnold, Susanne; Sitdikov, Airat G.; Castex, Dominique; Wahl, Joachim; Gazimzyanov, Ilgizar R.; Nurgaliev, Danis K.; Herbig, Alexander; Bos, Kirsten I.; Krause, Johannes (8 June 2016). "Historical Y. pestis Genomes Reveal the European Black Death as the Source of Ancient and Modern Plague Pandemics". Cell Host & Microbe. 19 (6): 874–881. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2016.05.012. PMID 27281573.

- Appleby 1980.

- Snowden, Frank M. (2019). Epidemics and Society: From the Black Death to the Present. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. pp. 79–80. ISBN 978-0-300-19221-6.

- Lenski, Richard E. (11 August 1988). "Evolution of Plague Virulence" (PDF). Nature. Springer Nature. 334 (6182): 473–474. Bibcode:1988Natur.334..473L. doi:10.1038/334473a0. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 3405295. S2CID 10386806.

Bibliography

- Alexander, John T. (1980), Bubonic Plague in Early Modern Russia: Public Health and Urban Disaster, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-515818-2

- Appleby, Andrew B. (1980), "The Disappearance of Plague: A Continuing Puzzle", The Economic History Review, 33 (2): 161–173, doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.1980.tb01821.x, JSTOR 2595837, PMID 11614424

- Barras, Vincent; Greub, Gilbert (2014). "History of biological warfare and bioterrorism". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 20 (6): 498. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12706. PMID 24894605.

- Benedictow, Ole Jørgen (2004), Black Death 1346–1353: The Complete History, Boydell Press, ISBN 978-1-84383-214-0

- Bramanti, Barbara; Stenseth, Nils Chr; Walløe, Lars; Lei, Xu (2016). "Plague: A Disease Which Changed the Path of Human Civilization". Yersinia pestis: Retrospective and Perspective. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 918. pp. 1–26. doi:10.1007/978-94-024-0890-4_1. ISBN 978-94-024-0888-1. ISSN 0065-2598. PMID 27722858.

- Bray, R. S. (2004-04-29), Armies of Pestilence: The Impact of Disease on History, James Clarke & Co., ISBN 978-0-227-17240-7

- Byrne, Joseph Patrick (2004), The Black Death, Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press

- Byrne, Joseph Patrick, ed. (2008), Encyclopedia of Pestilence, Pandemics, and Plagues: A-M, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-0-313-34102-1

- Davis, Robert C. (2003-12-05), Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters: White Slavery in the Mediterranean, the Barbary Coast and Italy, 1500–1800, Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-333-71966-4

- Gottfried, Robert S. (1983), The Black Death: Natural and Human Disaster in Medieval Europe, London: Hale, ISBN 978-0-7090-1299-3

- Graunt, John (1759), Collection of Yearly Bills of Mortality, from 1657 to 1758 Inclusive, A. Miller

- Harding, Vanessa (2002-06-20), The Dead and the Living in Paris and London, 1500–1670, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-81126-2

- Hays, J. N. (1998), The Burdens of Disease: Epidemics and Human Response in Western History, Rutgers University Press, ISBN 978-0-8135-2528-0

- Hays, J. N. (2005-12-31), Epidemics And Pandemics: Their Impacts on Human History, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-85109-658-9

- McNeill, William Hardy (1998), Plagues and peoples, Anchor, ISBN 978-0-385-12122-4

- Mikhail, Alan (2014), The Animal in Ottoman Egypt, OUP, ISBN 9780199315277

- Issawi, Charles Philip (1988), Fertile Crescent, 1800–1914: A Documentary Economic History, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-504951-0

- Parker, Geoffrey (2001-12-21), Europe in Crisis: 1598–1648, Wiley, ISBN 978-0-631-22028-2

- Porter, Stephen (2009-04-19), The Great Plague, Amberley Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84868-087-6

- Shadwell, Arthur; Hennessy, Harriet L.; Payne, Joseph Frank (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 693–705.

- Wade, Nicholas (31 October 2010), "Europe's Plagues Came From China, Study Finds", The New York Times, retrieved 1 November 2010

- Wheelis, Mark (2002). "Biological Warfare at the 1346 Siege of Caffa". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 8 (9): 971–75. doi:10.3201/eid0809.010536. PMC 2732530. PMID 12194776.

External links

Media related to Plague, second pandemic at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Plague, second pandemic at Wikimedia Commons