1943 Surprise Hurricane

The 1943 Surprise Hurricane was the first hurricane to be entered by a reconnaissance aircraft. The first tracked tropical cyclone of the 1943 Atlantic hurricane season, this system developed as a tropical storm while situated over the northeastern Gulf of Mexico on July 25. The storm gradually strengthened while tracking westward and reached hurricane status late on July 26. Thereafter, the hurricane curved slightly west-northwestward and continued intensifying. Early on July 27, it became a Category 2 hurricane on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale and peaked with winds of 105 mph (165 km/h). The system maintained this intensity until landfall on the Bolivar Peninsula in Texas late on July 27. After moving inland, the storm initially weakened rapidly, but remained a tropical cyclone until dissipating over north-central Texas on July 29.

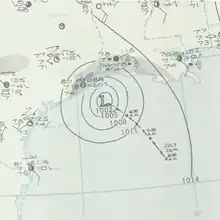

Surface weather analysis of the hurricane on July 27, near peak intensity. | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | July 25, 1943 |

| Dissipated | July 29, 1943 |

| Category 2 hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 105 mph (165 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 967 mbar (hPa); 28.56 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 19 |

| Damage | $17 million (1943 USD) |

| Areas affected | Louisiana, Texas |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 1943 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Because the storm occurred during World War II, information and reports were censored by the government of the United States and news media. Advisories also had to be cleared through the Weather Bureau office in New Orleans, resulting in late releases. This in turn delayed preparations ahead of the storm. In Louisiana, the storm produced gusty winds and heavy rains, though no damage occurred. The storm was considered the worst in Texas since the 1915 Galveston hurricane. Wind gusts up to 132 mph (212 km/h) were reported in the Galveston-Houston area. Numerous buildings and houses were damaged or destroyed. The storm caused 19 fatalities, 14 of which occurred after two separate ships sank. Overall, damage reached approximately $17 million (equivalent to $287 million in 2022).

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

A partial atmospheric circulation was observed over the extreme Southeastern United States and the eastern Gulf of Mexico as early as July 23. However, an area of disturbed weather went unnoticed until July 25, when wind shifts from southeast to northeast were observed in Burrwood and New Orleans in Louisiana, as well as Biloxi, Mississippi.[1] Around 1800 UTC, a tropical storm developed approximately 110 miles (180 km) southeast of the Mississippi River Delta.[2] Moving westward at about 7 mph (11 km/h),[3] the storm strengthened and became a hurricane late on July 26. Early on the following day, the storm strengthened into a Category 2 hurricane on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale. Around that time, the storm also attained its maximum sustained wind speed of 105 mph (165 km/h).[2]

Later on July 27, the first ever reconnaissance aircraft flight into a hurricane occurred. An eye feature with a width of 9–10 miles (14–16 km) was observed during the flight.[3] Around 1800 UTC on July 27, the storm made landfall on the Bolivar Peninsula in Texas with winds of 105 mph (165 km/h).[2] The system was described by the Weather Bureau as "a small intense storm accompanied by full hurricane winds."[1] Around the time of landfall, a barometric pressure of 967 mbar (28.6 inHg) was observed. Early on July 28, the system weakened to a Category 1 hurricane, then a tropical storm about six hours later. Later that day, the storm began curving northwestward over east-central Texas. Early on July 29, it weakened further to a tropical depression. Around 0000 UTC on the following day, the storm dissipated near Whitt, Texas.[2]

Hurricane hunting

This was the first hurricane that a reconnaissance aircraft intentionally flew into. During the morning hours of July 27, British pilots were training at Bryan Field in Bryan, Texas and were alerted about a hurricane approaching the Galveston area. Upon becoming informed that the planes would need to be flown away from the storm, they criticized this policy. Instead, Colonel Joe Duckworth made a bet with the British pilots that he could fly his AT-6 Texan trainer directly into the storm. Duckworth requested that Lt. Colonel Ralph O'Hair, the only navigator at the field, fly into the hurricane with him. Because neither Duckworth nor O'Hair believed that the headquarters would approve the flight, they decided to proceed without permission. Thus, Duckworth and O'Hair became the first hurricane hunters. O'Hair later compared the weather encountered during the flight to "being tossed about like a stick in a dog's mouth". After returning to Bryan Field, Lt. William Jones-Burdick requested to fly into the hurricane with Duckworth, while O'Hair decided to exit the aircraft.[3]

Censorship

The hurricane occurred during World War II, with activity from a German U-boat expected in the Gulf of Mexico. As a result, ship reports were silenced. At the time, the Weather Bureau relied primarily on ship and land weather station observations to issue storm warnings. Additionally, advisories had to be cleared through the Weather Bureau office in New Orleans, Louisiana, causing them to be released hours late; moreover, the advisories contained no forecast information, which would have allowed for preparation before the storm struck. The news media after the hurricane was heavily censored by the government due to national security, as information could not be leaked to the Axis powers about the loss of production of war materials. Reportedly, the Federal Bureau of Investigation shut down a telegraph office in La Porte after a telegram was sent containing information about damage from the hurricane. The only news of this storm was published in Texas and Louisiana. After the loss of life in this storm, the government of the United States has never censored hurricane advisories again.[3]

Impact and aftermath

In Louisiana, light winds were observed, with gusts of 36 mph (58 km/h) at both Burrwood and Lake Charles. Locally heavy rains were reported in some areas, with a 24-hour precipitation total of 7.65 inches (194 mm) in DeQuincy on July 28.[4]

The storm brought strong winds to Texas, with gusts up to 132 mph (212 km/h) reported at the cooling towers at the Shell Oil Refinery in Deer Park and the Humble Oil Refinery in Baytown. Four towers were destroyed at the latter, while other damage there reduced production of toluene, which is a precursor to TNT. Some towers were also toppled at the Shell Oil Refinery in Deer Park. As these were the primary refineries producing aviation fuel for World War II, it was decided that news about this loss of production should be censored. A number of other oil derricks were destroyed throughout Chambers and Jefferson counties. At Ellington Field Joint Reserve Base near Houston, strong winds blew off the top of a hangar, destroyed five planes, and injured at least 22 cadets.[3] Thousands in the Houston were left without telephone and electrical service,[5] which caused all three radio stations in the area to go off air. The nearby Houston Yacht Club also suffered heavy damage. At Point Bolivar, located on the Bolivar Peninsula, nearly all homes were destroyed by the high winds. The high school's physical education building in La Porte, which was originally a three story building, was reduced to only one floor after windows shattered and the support beams toppled, causing the roof to collapse. At nearby Morgan's Point, a water tower was knocked over.[3] On Galveston Island, a number of brick businesses, buildings, and churches collapsed.[6]

Heavy rainfall was observed in some areas of eastern Texas, with up to 19 inches (480 mm) in Port Arthur. There, numerous homes were flooded with 6 to 24 inches (150 to 610 mm) of water, which included damage to furnishings, electric motors and automobiles. In downtown Galveston, a number of streets were inundated with rainwater, though flooding damage was relatively minor.[3] Two children's polio hospitals suffered leaking roofs and water damage, forcing patients to be evacuated by staff and University of Texas Medical Branch students.[7] About 90 percent of all house and buildings in Texas City suffered either water damage or complete destruction, including plant sites producing war materials. However, they were discouraged from going to shelters due to a polio epidemic there. In Galveston Bay, wind-driven waves flooded the western and southern shores. However, northerly winds across the bay resulted in tides being extremely low. On Galveston Island, a storm surge of 6 feet (1.8 m) was observed. Offshore, the United States Army Corps of Engineers’s hopper dredge Galveston broke up after being smashed against the north jetty, causing 11 fatalities. The tug Titan began sinking offshore Port Arthur. Three members of the crew drowned after attempting to board a rubber raft, while another person died before the remainder of the crew reached the shore. Overall, the storm killed 19 people and caused $17 million (1943 USD) in damage to the Houston area.[3]

Following the storm, residents were warned to boil their water and be cautious of potential food contamination due to electrical outages. The War Production Board regional office in Dallas offered relief to the victims of the storm.[5] In La Porte, a makeshift hospital was set up in city hall. At Point Bolivar, where nearly all houses were destroyed, the now-destitute residents were transported by the Galveston chapter of the American Red Cross to Galveston for housing.[8]

See also

- 1941 Texas hurricane

- Hurricane Alicia

- Hurricane Otis - Another surprise hurricane that hit Acapulco Mexico in 2023

References

- Howard C. Sumner (November 1943). North Atlantic Hurricane And Tropical Disturbances of 1943 (PDF). Weather Bureau (Report). Washington, D.C.: Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. pp. 179–1980. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. April 5, 2023. Retrieved October 26, 2023.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Lew Fincher and Bill Read (May 24, 2010). The 1943 "Surprise" Hurricane. National Weather Service Houston/Galveston, Texas (Report). Dickinson, Texas: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- David M. Roth (April 8, 2010). Louisiana Hurricane History (PDF). Weather Prediction Center (Report). College Park, Maryland: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 35. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- "Severe Storm Hits City" (PDF). The Daily News. July 28, 1943. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 13, 2004. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- David M. Roth (January 17, 2010). Texas Hurricane History (PDF). Weather Prediction Center (Report). College Park, Maryland: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 46. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- Heather Green Wooten (October 25, 2009). The Polio Years in Texas: Battling a Terrifying Unknown. Austin, Texas: Texas A&M University Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-1603441650. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- "Ten Are Drowned As Dredge Sinks" (PDF). The Daily News. July 29, 1943. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 18, 2010. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

External links

- National Weather Service Forecast Office Houston, Galveston - Research Projects - The 1943 "Surprise" Hurricane, by Lew Fincher & Bill Read

- Galveston Daily News special report: "The mystery storm of 1943" by Ted Streuli