Hurricane Earl (1998)

Hurricane Earl was an atypical, disorganized, and short-lived Category 2 hurricane that caused moderate damage throughout the Southeast United States. It formed out of a poorly organized tropical disturbance over the southwest Gulf of Mexico late on August 31, 1998. Tracking towards the northeast, the storm quickly intensified into a hurricane on September 2 and made landfall early the next day near Panama City, Florida. Rapidly tracking towards Atlantic Canada, the extratropical remnants of Earl significantly intensified before passing over Newfoundland on September 6. The remnants were absorbed by former Hurricane Danielle two days later.

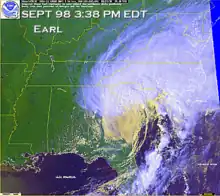

Earl near peak intensity shortly before making landfall in Florida late on September 2 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | August 31, 1998 |

| Extratropical | September 3, 1998 |

| Dissipated | September 8, 1998 |

| Category 2 hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 100 mph (155 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 985 mbar (hPa); 29.09 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 3 direct |

| Damage | $79 million (1998 USD) |

| Areas affected | Florida, Georgia, Carolinas, Atlantic Canada |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 1998 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Moderate beach erosion occurred along the coasts of Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida as waves reached 20 ft (6.1 m). Throughout Florida, nearly 2,000 homes were damaged and a few were destroyed. Severe flooding caused by storm surge and heavy rains was the main cause of damage in the state. Offshore, two men drowned after their boat capsized during the storm. A minor tornado outbreak took place in relation to Earl in Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina. A tornado in South Carolina killed one person after completely destroying the occupant's home. In all, three people were killed by Earl and damages were $79 million (1998 USD; $104.4 million 2009 USD).

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

Hurricane Earl originated out of a strong tropical wave that moved off the west coast of Africa on August 17. By August 23, a weak area of low pressure developed within the wave and well-developed convective activity was present as it tracked through the Lesser Antilles. Once in the Caribbean, strong wind shear produced by the outflow of Hurricane Bonnie inhibited further development of the system. As it remained well-defined, satellites easily followed the low pressure into the Gulf of Mexico. By August 31, the storm had become sufficiently organized for the National Hurricane Center (NHC) to classify it as Tropical Depression Five. At this time, the depression was located roughly halfway between Mérida and Tampico, Mexico.[1]

Operationally, the NHC immediately classified the system as Tropical Storm Earl based on a Hurricane Hunter Reconnaissance mission that found flight-level winds of 49 mph (79 km/h), corresponding to surface winds of 40 mph (64 km/h). Due to the existence of multiple circulation centers, the initial movement of the storm was uncertain, but forecasters anticipated a general northward movement.[2] In post-season analysis, it was determined that the system intensified into Tropical Storm Earl while located about 575 miles (925 km) south-southwest of New Orleans. Initial advisories on Earl relocated the center of circulation several times before focusing on the true circulation center.[1]

By September 1, the storm began to consolidate, with reconnaissance flights finding an elongated center and surface winds of 60 mph (97 km/h). Moderate wind shear inhibited convective development in the western portion; however, outflow in other areas of the storm improved, leading to further development. A northwest track, fully identified by this time as a mid-tropospheric ridge located over Florida, strengthened.[3] Remaining disorganized, Earl continued to intensify as the center of circulation was located close to deep convection. The NHC stated in their fifth advisory on the storm that Earl did not appear to be fully tropical due to the lack of organization.[4] Around 1200 UTC on September 2, Earl intensified into a hurricane despite having an atypical structure; the wind field of the storm was asymmetric and the strongest winds were located well to the southeast of the center.[1]

Several hours after becoming a hurricane, Earl further intensified into a Category 2 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Scale; this observation was based on a flight-level winds of 119 mph (192 km/h), which corresponded to surface winds of 100 mph (160 km/h). The storm did not feature an eye or partial eyewall.[5] The central barometric pressure continued to fall despite the fact that the storm was beginning to weaken. Around 0000 UTC on September 3, the central pressure decreased to 985 mbar (985 hPa; 29.1 inHg); however, winds also decreased to 90 mph (140 km/h).[1] As Earl neared landfall, cloud tops significantly warmed, indicating weakening, and the overall structure of the storm became less organized.[6]

Around 0600 UTC (1:00 am EDT) on September 3, Hurricane Earl made landfall near Panama City, Florida with winds of 80 mph (130 km/h).[1] Shortly after landfall, the storm weakened to a tropical storm and rapidly accelerated as it quickly underwent an extratropical transition. By this time the NHC issued their final advisory on Earl.[7] Several hours later, Earl finished its transition and continued to rapidly track through the Southeast United States. After entering the Atlantic Ocean, the remnants of Earl began re-intensify due to the effects of a baroclinic zone. Relatively cool sea surface temperatures near Atlantic Canada prevented tropical development; however, during a 36-hour span, Earl rapidly intensified, as the central barometric pressure decreased by 40 mbar (hPa; 1.18 inHg) to 957 mbar (hPa; 28.26 inHg).[8] By the time the system made landfall over eastern Newfoundland, sustained winds had intensified to 65 mph (105 km/h). On September 8, the remnants of Earl significantly weakened and were soon absorbed by a larger extratropical cyclone associated with the remnants of Hurricane Danielle.[1]

Preparations

As Earl tracked towards the northeastern Gulf of Mexico on September 1, a hurricane warning was issued for coastal areas between Pascagoula, Mississippi and Cameron, Louisiana. Additionally, hurricane watches extended out to Destin, Florida and High Island, Texas from the edges of the warning respectively. Early the next day, a tropical storm warning was issued for areas between Pascagoula, Mississippi and Destin, Florida. In response to the eastward movement of the hurricane, the hurricane watch and warning was discontinued for areas west of Morgan City, Louisiana. Additionally, the hurricane warning was extended eastward to Destin, Florida, a tropical storm warning was issued east of Destin to Apalachicola, Florida, and a tropical storm watch was declared for areas between Morgan City and Cameron, Louisiana. Several hours later, the hurricane warning was again extended eastward to the mouth of the Suwannee River. All watches and warnings were discontinued for areas west of Pascagoula, Mississippi and due to the asymmetrical structure of Hurricane Earl, a tropical storm warning was issued as far south as the Florida Keys. Continuing uncertainty in the track of Earl prompted the issuance of a hurricane watch and tropical storm warning for areas between Pascagoula, Mississippi and Grand Isle, Louisiana, including the city of New Orleans. After Earl made landfall in Florida, all watches and warnings were discontinued in relation to the storm.[1]

Offshore, several oil and natural gas rigs were evacuated due to the proximity of Earl.[9] An estimated 10,000 workers were evacuated from both onshore and offshore rigs.[10] The storm forced many Florida residences to evacuate, especially people living in the barrier islands along the Florida Gulf Coast. About 30 Air Force jets from Eglin Air Force Base were sent to Oklahoma to protect them from the storm.[11] A mandatory evacuation was issued for 20,000 residents in Leon County as well as all barrier islands along the Florida coast due to the risk of substantial flooding. Franklin County was briefly under a mandatory evacuation order on September 2, the reasons for the lifting of the order are unknown.[12] State parks along the Florida Panhandle were also closed and highways became congested with thousands of residents and tourists evacuating the barrier islands.[13]

Along the Louisiana coastline, voluntary evacuation orders were given out.[11] A state of emergency was declared for portions of southeast Louisiana as tides in relation to the storm were forecast to reach 7 to 10 ft (2.1 to 3.0 m). Emergency shelters were opened throughout Plaquemines Parish, schools were closed in many areas, and the floodgates around New Orleans were shut.[14] An estimated 5,000 people evacuated to inland areas throughout Louisiana.[10] In Nueces County, Texas, work crews worked quickly to clear garbage along the streets and picked up trash cans to avoid possible problems with clogged drains.[14] Throughout the Alabama and Mississippi coasts, schools were closed due to the storm.[13]

Impact

Throughout the Southeast United States, Hurricane Earl killed three people and caused $79 million (1998 USD; $104.4 million 2009 USD) in damages.

Florida

Ahead of Hurricane Earl's landfall in Florida, several tornadoes were spawned along the outer bands of the storm. The first tornado to touch down was a brief F0 that caused no known damage.[15] The second tornado, rated F1, caused moderate damage to three homes and two buildings that were under-construction along its 3 mi (4.8 km) path.[16] During a 15-minute span, three brief F0 tornadoes touched down in unpopulated areas, causing minor tree damage.[17][18][19] Several hours later, a strong F1 tornado touched down in Port Canaveral. The tornado damaged 14 cars, eight condominiums, four businesses, a mobile home, and a fire station. In all, the tornado caused $6 million in damages and injured one person.[20] On St. George Island, an F1 tornado damaged six homes, leaving $150,000 in damages.[21] High waves, estimated at 16 to 20 ft (4.9 to 6.1 m) caused a boat to capsize off the coast of Panama City, drowning both occupants.[22]

Upon making landfall in Florida early on September 3, Earl produced a storm surge up to 12 ft (3.7 m) in the Big Bend, inundating coastal communities.[22] Torrential rains, peaking at 16.36 in (416 mm) around Panama City, fell throughout the Florida Panhandle.[23] Significant beach erosion was recorded in Walton County, Carrabelle Beach and Alligator Point. The most extensive damage occurred in Bay County where 1,112 structures damaged by flooding and three were destroyed. In Panama City, upwards of 5 ft (1.5 m) of water flooded homes. An estimated 7,100 residents in Bay County lost power during the storm. Florida officials temporarily shut down numerous major roadways, including State Road 77 due to high water. Portions of two roads in coastal Liberty County were destroyed due to beach erosion. In Gulf County, 300 homes were damaged by high winds and floodwaters. An estimated 8,700 people lost power in the county during the storm. At Port St. Joe, Earl's storm surge inundated 14 businesses and caused a water main break in the Lighthouse Utilities facility. In Franklin County, storm surge damaged 136 homes and 15 businesses and led to a temporary closure of the St. George Causeway.[22] A lighthouse on St. George Island was also destroyed by the storm.[24]

At least 50 people were stranded in Alligator Point after floodwaters washed out the main access route to the town. In Wakulla County, 216 homes and businesses were damaged by high winds and flooding. Severe flooding in coastal Taylor County caused significant damage in nine communities. County officials reported that 66 structures were damaged by Earl. Five homes were destroyed and 39 others were damaged by flooding in Dixie County.[22] In Highlands County, one person was injured after being struck by lightning.[25] On September 3, the strongest tornado spawned by Earl in Florida touched down in Citrus County. Rated F2, the tornado tracked for 5 mi (8.0 km), destroying eight homes and damaging 24 others. Several trees and power lines were also downed. Two people were injured in one of the destroyed homes and damages from the tornado amounted to $500,000.[26] In all, Hurricane Earl killed two people and caused $73 million (1998 USD; $96.5 million 2009 USD) in Florida.[1]

Southeastern U.S.

In Louisiana, moderate beach erosion occurred as tides reached 3.5 ft (1.1 m) above mean sea level.[10] Rainfall was relatively light, peaking around 2 in (51 mm) in Morgan City, as only the outer bands of Earl affected the state.[23] The highest winds occurred along the coast, with sustained winds reaching 30 mph (48 km/h)[10] and gusts reaching 44 mph (71 km/h) in Venice, Louisiana.[27] Only minimal damage resulted from the storm in Louisiana, with monetary losses amounting to $32,000. However, losses due to the large-scale evacuation of oil and natural gas rigs was estimated to be several million dollars.[10] Earl had limited impacts in Mississippi, with only areas along the immediate coast recording tropical storm-force wind gusts.[28] In Alabama, Earl produced moderate rainfall, with areas along the Georgia state line receiving more than 5 in (130 mm). Despite the center of Earl passing close to the state, winds were only recorded up to 40 mph (64 km/h), resulting in scattered power outages and downed trees. Portions of Alabama State Route 28 were temporarily shut down due to debris covering the road. In all, damages in the state amounted to $120,000.[29]

Ahead of Earl, an onshore flow related to the storm produced 6 to 8 ft (1.8 to 2.4 m) swells along the Georgia coast, causing significant damage to marinas. The Mar Lin Marina sustained the most damage from this event; all the docks were destroyed, 30 boats were damaged and six were destroyed. Damages to the marina and boats amounted to $1.3 million.[30] Heavy rains fell throughout central areas of the state, with the highest amounts nearing 10 in (250 mm). Because Earl rapidly weakened upon landfall, the highest winds in Georgia only reached 54 mph (87 km/h). Numerous trees and power lines were downed, resulting in scattered power outages.[31] Throughout Georgia, an estimated 10,400 people lost power due to Earl.[32] Several streets were flooded due to the rains, resulting in traffic accidents.[31] One tornado was spawned by Earl in Georgia; rated F2 on the Fujita scale, the tornado tracked for 8 mi (13 km) in Screven County. Estimated at 350 yd (320 m) in width, the tornado destroyed five mobile homes and a business, severely damaged 15 additional mobile homes and caused some damage to five others. Seven people were injured by the tornado and damages amounted to $435,000.[33] Several major highways were temporarily closed due to high water or debris covering the road. Numerous homes sustained damage from fallen trees in several counties. In all, damages from Earl amounted to $2.3 million in Georgia.[30][32][33]

The extratropical remnants continued through the Southern United States, tracking through the Carolinas late on September 3. Sustained winds in South Carolina reached 50 mph (80 km/h) and gusted up to 70 mph (110 km/h). Widespread rainfall, generally amounting between 2 and 4 in (51 and 102 mm), fell in areas previously saturated by Hurricane Bonnie, this triggered minor flooding along roads.[34] Inland, isolated amounts of 10 in (250 mm) of rain fell.[23] The first tornado related to Earl touched down in Choppee, located in Georgetown County. The tornado was rated F0 and was only briefly on the ground before it dissipated.[34] The second tornado to touch down in the state was also the strongest in relation to Earl. Rated F2, the tornado tracked for 18 mi (29 km) through Beaufort and Colleton Counties, destroying 13 homes and damaging 13 others. One mobile home was flipped in the air and was completely destroyed once it hit the ground, instantly killing the occupant of the home. Numerous trees were uprooted and snapped along its path. In all, the tornado killed one person, injured four others and caused $360,000 in damages.[35][36] A brief F1 tornado touched down several hours later, damaging the roof of a barn and uprooting several trees before dissipating.[37] The most damaging tornado spawned by Earl was a 430 yd (390 m) wide, F2 tornado that struck the Fairlawn subdivision near Moncks Corner. Along the tornado's 7 mi (11 km) track, 21 homes were destroyed and 73 others were damaged. Nine people sustained injuries due to the tornado and damages amounted to $2.8 million.[38]

Still recovering from Hurricane Bonnie, the remnants of Earl produced widespread rain over North Carolina, triggering flooding.[23] Upwards of 6 in (150 mm) fell in localized areas, causing small streams to overflow their banks.[39] In Union County, up to 15 roads were shut down due to flooding, a few cars were also washed off roads at the height of the floods. In Charlotte, several roads were flooded.[40] The Carteret Community College, which was severely damaged by Bonnie, was again damaged by Earl. High winds from the storm damaged temporary protective measures, allowing rain to flood the interior of the building, causing water damage to the structure and materials inside. In front of the Crystal Coast Civic Center, fabriform, installed to stabilize the beach, was damaged by the storm, resulting in significant beach erosion.[41] Two short lived tornadoes touched down in North Carolina from Earl. The first, an F0, damaged at least 15 mobile homes, overturned sheds, destroyed a porch and two campers. No injuries resulted from the tornado and damage amounted to $50,000.[42] The second and stronger of the two tornadoes, rated F1, only touched down for a few seconds; however, it destroyed one home and severely damaged a neighboring home. According to eye-witness reports, the tornado lifted the home 20 to 25 ft (6.1 to 7.6 m) off the ground before the home broke apart and fell to the ground.[43]

Elsewhere

The initial tropical disturbance passed through the Yucatán Peninsula on August 29 and inflow bands to the south of Earl continued rainfall across southeast Mexico until early September 2. The highest rainfall total was reported from Belizario Dominguez/Moto, where 12.94 in (329 mm) of precipitation fell.[23]

The extratropical remnants of Earl produced strong winds and heavy rains throughout Newfoundland and Nova Scotia on September 6.[44] Sustained winds were recorded up to 56 mph (90 km/h) and rains totaled between 2 and 4 in (51 and 102 mm) throughout Newfoundland. On Nova Scotia, rainfall peaked at 4.62 in (117 mm) on Cape Breton Island. The highest recorded total on Newfoundland reached 3.54 in (90 mm) in northwestern areas of the island.[8]

Aftermath

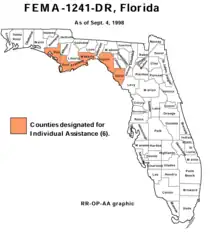

On September 4, President Bill Clinton approved disaster declarations for six counties in Florida. Bay, Dixie, Franklin, Gulf, Taylor, and Wakulla counties were approved for Individual Assistance.[45] Residents in the designated counties were eligible to receive federal funding for three months following the storm.[46] By September 8, State Farm had received 200 auto and 720 homeowners claims from the affected region, most of which were partial damage claims. Allstate had received 80 auto and 587 homeowners claims from Florida and 540 claims from Georgia. Additionally, Nationwide reported that up to 1,000 claims had been filed from Florida.[47]

Following the impacts of Hurricane Opal in 1995, Earl and later Hurricane Georges, the state of Florida undertook a recovery project to restore the eroded beaches along the Panhandle coast.[24] In October United States Department of Transportation provided $2 million in funds to repair damaged and destroyed roads in Florida. On December 3, an additional $1.7 million was provided to repair funds.[48] The United States Military allocated $2.2 million to repair damage from Hurricane Earl to training academies and naval ports.[49] The Florida Senate provided $25,740 in emergency funds to Hurricane Earl victims.[50] By the end of the disaster declaration, the Federal Emergency Management Agency provided $1 million in public assistance and $600,000 in disaster mitigation.[51]

References

- Max Mayfield (November 17, 1998). "Hurricane Earl Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 2, 2010. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Pasch (August 31, 1998). "Tropical Storm Earl Discussion One". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Avila (September 1, 1998). "Tropical Storm Earl Discussion Four". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Pasch (September 1, 1998). "Tropical Storm Earl Discussion Five". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Avila (September 2, 1998). "Hurricane Earl Discussion Ten". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Pasch (September 3, 1998). "Hurricane Earl Discussion Eleven". National Hurricane Center.

- Rappaport (September 3, 1998). "Tropical Storm Earl Discussion Thirteen (Final)". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Suhong Ma; Harold Ritchie; John Gyakum; Jim Abraham; Chris Fogarty; Ron McTaggart-Cowan (August 30, 2002). "A Study of the Extratropical Reintensification of Former Hurricane Earl". Monthly Weather Review. World Meteorological Organization. 131: 1342. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(2003)131<1342:ASOTER>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0493. S2CID 56421331. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Cliff Edwards (September 2, 1998). "Natural gas tumbles as Hurricane Earl sidesteps major producing areas". Associated Press. Archived from the original on October 25, 2012. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Stuart Hinson (1998). "Louisiana Event Report: Hurricane". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Bill Kaczor (September 2, 1998). "Earl veers eastward and grows into hurricane". Associated Press. Archived from the original on October 25, 2012. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Bill Kaczor (September 3, 1998). "Hurricane Earl hits Florida's Panhandle". Associated Press. Archived from the original on October 25, 2012. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Bill Koczar (September 2, 1998). "Hurricane Earl veers toward Florida coast". Associated Press. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Catherine Wilson (September 2, 1998). "Tropical Storm Earl expected to become hurricane and hit Gulf coast". Associated Press. Archived from the original on October 25, 2012. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Stuart Hinson (1998). "Florida Event Report: F0 Tornado". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Stuart Hinson (1998). "Florida Event Report: F1 Tornado". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Stuart Hinson (1998). "Florida Event Report: F0 Tornado". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Stuart Hinson (1998). "Florida Event Report: F0 Tornado". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Stuart Hinson (1998). "Florida Event Report: F0 Tornado". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on April 30, 2001. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Stuart Hinson (1998). "Florida Event Report: F1 Tornado". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Stuart Hinson (1998). "Florida Event Report: F1 Tornado". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Stuart Hinson (1998). "Florida Event Report: Hurricane". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- David M. Roth (2009). "Hurricane Earl - September 1–5, 1998". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Department of Environmental Protection (1999). "Beach and Dune Erosion and Structural Damage and Post-Storm Recovery Plan for the Panhandle Coast of Florida" (PDF). State of Florida. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Stuart Hinson (1998). "Florida Event Report: Lightning". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Stuart Hinson (1998). "Florida Event Report: F2 Tornado". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Stuart Hinson (1998). "Louisiana Event Report: Tropical Storm". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Stuart Hinson (1998). "Mississippi Event Report: Tropical Storm". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Stuart Hinson (1998). "Alabama Event Report: Tropical Storm". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Stuart Hinson (1998). "Georgia Event Report: Thunderstorm Winds". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Stuart Hinson (1998). "Georgia Event Report: High Winds". National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on June 13, 2007. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Stuart Hinson (1998). "Georgia Event Report: Tropical Storm". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Stuart Hinson (1998). "Georgia Event Report: F2 Tornado". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Stuart Hinson (1998). "South Carolina Event Report: F0 Tornado". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Stuart Hinson (June 7, 1998). "South Carolina Event Report: F2 Tornado". National Climatic Data Center.

- Stuart Hinson (June 7, 1998). "South Carolina Event Report: F1 Tornado". National Climatic Data Center.

- Stuart Hinson (1998). "South Carolina Event Report: F1 Tornado". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Stuart Hinson (1998). "South Carolina Event Report: F2 Tornado". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Stuart Hinson (1998). "North Carolina Event Report: Flash Flood". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Stuart Hinson (1998). "North Carolina Event Report: Flood". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Stuart Hinson (1998). "North Carolina Event Report: Heavy Rain". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Stuart Hinson (1998). "North Carolina Event Report: F0 Tornado". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Stuart Hinson (1998). "North Carolina Event Report: F1 Tornado". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Richard J. Pasch; Lixion A. Avila; John L. Guiney (1999). "Monthly Weather Review for 1998" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 7, 2009. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- Federal Emergency Management Agency (September 4, 1998). "Designated Counties for Florida Hurricane Earl". Government of the United States. Archived from the original on May 8, 2009. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- Federal Emergency Management Agency (September 8, 1998). "Summary: Hurricane Earl in Florida". Government of the United States. Archived from the original on May 31, 2009. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- Adams, Michael H. (September 8, 1998). "Insurers 'Dodge Bullet' On Hurricane Earl Losses". National Underwriter Property & Casualty-Risk & Benefits Management. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- Jim Pinkelman (December 3, 1998). "Transportation Secretary Slater Announces $1.7 Million in Emergency Relief Funds For Hurricane-Damaged Roads in Florida". United States Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on May 20, 2008. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- Staff Writer (1999). "Facilities Repair". The Library of Congress. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- Staff Writer (September 1999). "Funding for the Hurricane Loss Mitigation Program" (PDF). The State of Florida. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- Staff Writer (1999). "Mitigation Success". State of Florida. Archived from the original on November 25, 2002. Retrieved June 8, 2009.