Sudanese transition to democracy

A series of political agreements among Sudanese political and military forces for a democratic transition in Sudan began in July 2019. Omar al-Bashir overthrew the democratically elected government of Sadiq al-Mahdi in 1989[1] and was himself overthrown in the 2019 Sudanese coup d'état, in which he was replaced by the Transitional Military Council (TMC) after months of sustained street protests.[2] Following further protests and the 3 June Khartoum massacre, TMC and the Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC) alliance agreed on 5 July 2019 to a 39-month transition process to return to democracy, including the creation of executive, legislative and judicial institutions and procedures.[3]

|

|---|

|

|

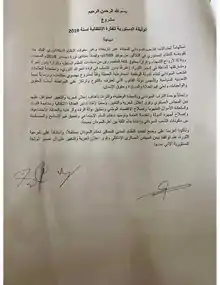

On July 17, 2019,[4] the TMC and FFC signed a written form of the agreement.[5] The Darfur Displaced General Coordination opposed the 5 July verbal deal,[6] and the Sudan Revolutionary Front,[7] the National Consensus Forces,[8] and the Sudanese Journalists Network opposed the 17 July written deal.[9] On 4 August 2019, the Draft Constitutional Declaration was initially signed by Ahmed Rabee for the FFC and by the deputy head of the TMC, Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo ("Hemetti"),[10][11] in the presence of Ethiopian and African Union mediators,[12] and it was signed more formally by Rabee and Hemetti on 17 August in the presence of international heads of state and government.[13]

The transition was interrupted on 25 October 2021 when the Sudanese military, led by General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, took control of the government in a military coup. The Hamdok government was reinstalled less than a month later, and the transition continued. Hamdok resigned on 2 January 2022 amid continuing protests, and the military reassumed power afterward.

Background

Previous democratic experiences

Sudan's 1948 election took place while Sudan was still under Anglo–Egyptian rule, with the question of union or separation from Egypt being a major electoral issue.[14][15] After independence in 1956, the following half century included a mix of national elections, constitutions, coalition governments, coups d'état, involvement in the Chadian Civil War (2005–2010), islamisation under the influence of Hassan al-Turabi (1989–1999) and the secession of South Sudan (2011).

Al-Bashir rule

Omar al-Bashir's rule started with the 1989 Sudanese coup d'état and ended with the April 2019 Sudanese coup d'état during the Sudanese Revolution (December 2018 – September 2019).

2019–2020

5 July verbal deal

On 5 July, with the help of African Union mediator Mohamed El Hacen Lebatt[16] and Ethiopian mediator Mahmoud Drir,[17] a verbal deal was reached by the TMC and the Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC) alliance, including Siddig Yousif and Ibrahim al-Amin,[3][17] on the formation of governmental institutions, under which the presidency of the transitional government would rotate between the military and civilians.[18]

The initial verbal deal agreed to by the TMC and the civilian negotiators included the creation of a "sovereignty council", a 39-month transition period leading to elections, a cabinet of ministers, a legislative council, and an investigation into the Khartoum massacre.[18]

Tahani Abbas, a cofounder of No to Women's Oppression, stated her worry that women might be excluded from the transition institutions, arguing that women "[bear] the brunt of the violence, [face] sexual harassment and rape" and were active in organising the protests.[3] The Minnawi and al-Nur factions of the Sudan Liberation Movement/Army, a Darfur armed rebel group, both stated on 5 July that they rejected the deal, arguing that the deal would not achieve an "equal citizenship state".[19] The Rapid Support Forces attacked people celebrating the deal in Abu Jubaiyah by beating them, firing tear gas, and shooting live bullets into the air. One person was hospitalised for serious wounds.[20]

17 July written Political Agreement

Following the 5 July verbal agreement, drafting of a written agreement by a committee of lawyers, including African Union lawyers, was promised to take place "within 48 hours".[18] On 9 July, the 4-person drafting committee, including Yahia al-Hussein, stated that the text had not yet been finished. The new time schedule was for the agreement to be signed "within ten days" in a ceremony including regional leaders.[21] On 13 July, three sticking points delaying the signing of the agreement included the FFC requiring the human rights investigation committee to exclude people suspected of responsibility or implementation of the 3 June Khartoum massacre; the FFC requiring a limit on the time frame for appointing the legislative council; and disagreement between the FFC and the TMC regarding TMC "endorse[ment] or [approval] of the nominees".[22] A written form of the deal as a "political agreement",[5] with a constitutional declaration to follow later, was signed by the TMC and FFC on 17 July.[4]

Objections to the 5 and 17 July 2019 agreements

The Darfur Displaced General Coordination, representing people from Darfur displaced in relation to the Darfur genocide, objected to the 5 July verbal agreement, describing it as "flawed in form and content" and "a desperate attempt to sustain the rule of the National Congress Party", the dominant political party of Omar al-Bashir's 30-year rule of Sudan.[6]

In the days following the 17 July written deal,[5] rebel groups represented by the Sudan Revolutionary Front (SRF),[7] the National Consensus Forces (NCF), a coalition of political parties that opposed al-Bashir's National Congress,[8] and the Sudanese Journalists Network[9] objected to the signed written agreement. The NCF and the SRF said that the FFC had signed the deal in Khartoum without waiting for the NCF and other opposition forces, who had still been discussing the proposed deal in Addis Ababa.[8][7] The NCF stated that the deal "goes towards granting of power to the military junta", and that the deal does not provide for an international investigation into "crimes committed throughout" al-Bashir's rule.[8] The Sudanese Journalists Network said that the written deal "strengthens the power of the junta, ... and tries to usurp power by stealing the efforts, sweat and blood of the revolution." The NCF called for the draft constitutional declaration to be circulated for comment prior to signing so that it take into account NCF's concerns.[8]

4 August/17 August Draft Constitutional Declaration

On 4 August 2019, the Draft Constitutional Declaration[10][11] (or Draft Constitutional Charter) was signed by Ahmed Rabee on behalf of the FFC and by the deputy head of the TMC, Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo ("Hemetti"), in the presence of Ethiopian and African Union mediators.[12] The document is composed of 70 legal articles, divided into 16 chapters, that outline transitional state bodies and procedures.[10][11] On 17 August 2019, Rabee and Hemetti signed the document more formally on behalf of the FFC and the TMC, respectively, in the presence of Abiy Ahmed, Prime Minister of Ethiopia, Salva Kiir, President of South Sudan, and other heads of state and government.[13]

Objections to the 4 August 2019 Draft Constitutional Declaration

The Darfur Displaced General Coordination objected to the 4 August Draft Constitutional Declaration, arguing that peace requires the disarming of militias; provision of all five suspects wanted in the International Criminal Court investigation in Darfur and the expulsion of new settlers from traditionally owned land in Darfur.[23] Minni Minawi stated that the SRF objected to the Draft Constitutional Declaration on the grounds that an agreement made among component groups of the FFC in Addis Ababa concerning mechanisms for a nationwide peace process in Sudan was excluded from the declaration and that the declaration constituted a power-sharing agreement between the FFC and the TMC.[24]

Legal reform

The legal reform was initiated by the Political Agreement of 17 July 2019, Article 20 of which mandated 'a legal reform program and rebuilding and developing the justice and rights' system and ensure the independence of judiciary and the rule of law.'[25] Many of the reforms affect the Sudanese Criminal Code of 1991 (also known as the Criminal Act or Penal Code).[26]

Some attempts had been made under al-Bashir's rule to reform legislation on issues such as extramarital rape victim blaming via 'adultery', and impunity for marital rape, by amending the definition of rape in Article 149.1 of the Criminal Code in February 2015. However, several commentators such as the African Centre for Justice and Peace Studies argued that this amendment had a number of flaws. Even though the amendment made it possible to prosecute marital rape by removing the reference to adultery, there is still no specific prohibition of marital rape, and oral rape is not criminalised. Moreover, Article 149.2 still defined adultery and sodomy as forms of 'rape', so complainants still risked being prosecuted for adultery or sodomy if they failed to prove they were subjected to sexual acts without their consent. Finally, the importance of consent was diminished in favour of coercion, going against the trend in international law to define sexual violence by lack of consent.[27]

Constitutional principles of legal reform (August 2019)

The Draft Constitutional Charter (also known as the Draft Constitutional Declaration) that was agreed in August 2019 further detailed how this reform was to take place during a 39-month transitional period, and in which areas of law these were to be focused. Article 2 of the Charter specifies that 'The Transitional Constitution of Sudan of 2005 and the constitutions of provinces is [sic] repealed, while the laws issued thereunder remain in force, unless they are repealed or amended. The decrees issued from 11 April 2019 until the date of signature of this Constitutional Charter remain in force, unless they are repealed or amended by the Transitional Military Council. If they contradict any provisions of this Constitutional Charter, the provisions of the present Declaration prevail.'[28]

Articles 3 and 5 outline what kind of state and society Sudan is, or should become: a parliamentary democracy with equal citizenship for all, that is 'founded on justice, equality, and diversity and guarantees human rights and fundamental freedoms,' where the rule of law prevails and 'violations of human rights and international and humanitarian law' and other transgressions are punished, including those committed by the 1989-2019 regime (a point reiterated in Article 7.3). Article 4 establishes the principle of popular sovereignty, and that provisions of existing laws 'that contradict the provisions of this Constitutional Charter shall be repealed or amended to the extent necessary to remove the contradiction'.[28]

Articles 6 and 7 outline the transitional process by which Sudan will be transformed into what kind of society it should become. Article 7.5 is an almost exact copy of Article 20 of the Political Agreement, thus reiterating the general commitment to legal reform. Further specifications are mentioned:

- 7.2 'Repeal laws and provisions that restrict freedoms or that discriminate between citizens on the basis of gender.'

- 7.7 'Guarantee and promote women’s rights in Sudan in all social, political, and economic fields, and combat all forms of discrimination against women, taking into account provisional preferential measures in both war and peace.'

- 7.15 'Dismantle the June 1989 regime's structure for consolidation of power (tamkeen), and build a state of laws and institutions.'[28]

Articles 41 to 66 provide a set of fundamental human and civil rights and freedoms that all Sudanese citizens are entitled to. Notably, Article 50 prohibited 'torture or harsh, inhumane, or degrading treatment or punishment, or debasement of human dignity.' Furthermore, Article 53 envisioned restriction of the death penalty to cases of 'retribution (qasas), a hudud punishment, or as a penalty for crimes of extreme gravity, in accordance with the law', exempting people younger than 18 or older than 70 years from execution, and postponing execution for pregnant and breastfeeding women.[28]

Repeal of the public order law (November 2019)

The [public order] laws were designed

to intentionally oppress women.

Abolishing them means a step forward

for the revolution in which masses of

women have participated. It's a very

victorious moment for all of us.

– Yosra Fuad (29 November 2019)[29]

On 29 November 2019, Article 152 of the Criminal Code (commonly referred to as the Public Order Law or the Public Order Act) was repealed.[30][31] It was controversial for various reasons, for example, because it was used to punish women who wore trousers in public by lashing them 40 times.[31] Other restrictions targeting women that were repealed included the lack of freedom of dress (by the mandatory hijab and other measures), movement, association, work and study. Alleged violations (many of whom were considered 'arbitrary' by activists) were punished with arrest, beatings and deprivation of civil rights such as freedom of association and expression.[29] According to Ihsan Fagiri, leader of the No to Oppression Against Women Initiative, around 45,000 women were prosecuted under the Public Order Act in 2016 alone. It was seen as an important first step towards gradual legal reform to improve the status of women's rights in the country as envisioned by the Charter.[31]

On the same day, the Dismantling of the Salvation Regime Act was adopted, which disbanded the former ruling National Congress Party of Omar al-Bashir, set up a committee to confiscate the vast assets of the party (many of which were allegedly illegitimately obtained from the population through 'looting', 'stealing' and corruption), and banned 'the symbols of the regime or party' from 'engaging in any political activity for a period of 10 years'.[32]

Miscellaneous Amendments Act (April–July 2020)

On 22 April 2020, the Transitional Legislative Council passed a series of bills that would amend other parts of the Criminal Code of 1991. Amongst other things, female genital mutilation (FGM) was criminalised and made punishable by a fine and 3 years imprisonment.[33] The resulting legal changes were bundled as the 'Miscellaneous Amendments Act' (also called 'Fundamental Rights and Freedoms Act' by some media[34][35]) and sent to the Sovereignty Council for approval, which took several months to review them. According to Justice Minister Nasreldin Abdelbari, some details were added to the Act by the Ministry of Justice following comments made by the Sovereignty Council 'in a manner that does not undermine the law'.[36] The Miscellaneous Amendments Act was finally signed by Sovereignty Council Chairman Abdel Fattah al-Burhan[35] and published in the Official Gazette on 9 July 2020 and thus became law.[37]

The Miscellaneous Amendments Act (or 'Fundamental Rights and Freedoms Act'[35]) had various consequences, including the following:

- Female genital mutilation (FGM) was criminalised and made punishable by a fine and 3 years imprisonment.[33]

- Apostasy by Muslims was no longer punishable by death, and takfir was criminalised. Article 126 of the Criminal Code of 1991 had prescribed the death penalty or life imprisonment for renouncing Islam.[38] Reportedly, apostasy was still illegal, although the punishment for it was not clear, while prosecutors were ordered to protect those accused of apostasy.[39]

- Women no longer needed to obtain permission from a male relative to travel abroad with their children.[37][38]

- Flogging as a form of punishment was abolished.[38]

- The sodomy law was amended: male participants in anal sex (sodomy, whether between two men or between a man and a woman) were no longer punishable by death or flogging, but still punishable by imprisonment.[40]

- Non-Muslims (an estimated 3% of the Sudanese population) were no longer banned from selling, importing and consuming alcohol (Articles 78 and 79).[35] Meanwhile, Muslims were still prohibited from drinking alcohol, and the law did not address the opening of bars, which Abdelbari deemed to be a more complicated matter to be discussed in the future.[39] He stated that if a Muslim and a non-Muslim were found drinking alcohol together, the latter might be charged with complicity.[36]

- The Information Law was amended to lower punishments for any violation; it was nevertheless deemed important that the prosecutor could legally counter 'rumours and false allegations'.[39]

Moreover, a bill reforming the legal and justice system and the Anti-Cyber Crime Act were signed into law on the same day as well.[35]

Religion/state separation and recognition of diversity (September 2020)

As part of the ongoing peace process between the transitional government and various rebel groups, an agreement was reached on 3 September 2020 in Addis Ababa to separate religion and state and not discriminate against anyone's ethnicity in order to secure the equal treatment of all citizens of Sudan. The declaration of principles stated that 'Sudan is a multi-racial, multi-ethnic, multi-religious and multi-cultural society. Full recognition and accommodation of these diversities must be affirmed. (...) The state shall not establish an official religion. No citizen shall be discriminated against based on their religion.'[41] Secularism had long been a demand of the SPLM-North al-Hilu rebel faction, with a spokesperson saying: 'The problem is (...) to address why people became rebels? Because there are no equal citizenship rights, there is no distribution of wealth, there is no equal development in the country, there is no equality between black and Arab and Muslim and Christian.'[42]

Reactions and demands from activists

Women's rights activists such as 500 Words magazine editor Ola Diab and Redress legal advisor Charlie Loudon hailed the abolition of repressive measures and restrictions on women as 'great first steps'. They emphasised that the new laws needed to be enforced and the repealed laws also abandoned in practice, which would require revision of the internal policies of government agencies such as the police, the military and intelligence services. Several other laws that activists demanded to be removed included the prosecution of rape victims for 'adultery' (Article 149.2), and of women in mixed-sex settings for 'prostitution' (Article 154),[31] other articles dictating women's dress code, and the disbandment of the public order police and dedicated courts that were part of the 'public order regime'.[29] Justice Minister Abdelbari stated in July 2020 that he was also considering to abolish the Personal Status Law to protect women's rights.[36] Strategic Initiative for Women in the Horn of Africa (SIHA) Regional Director Hala al-Karib praised the Act "as a good step in the right direction", but urged the transitional government to press on with more reforms, pointing out that the guardianship system was still enforced through other legislation such as 'passports, immigration and the issuance of official documents and even the record of deaths and births'.[37] Al-Karib also called upon the government to sign, ratify and abide by the provisions of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) and the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa (Maputo Protocol).[37] Other activists claimed there were still other forms of 'legal discrimination' that made women vulnerable to violence such as 'marital rape, and [being] prevented from leaving the home, working, choosing where to live, and [being] treated less equally by other family members.'[37]

Sudanese LGBT+ activists hailed the abolition of the death penalty and flogging for anal sex as a 'great first step', but said it was not enough yet, and the end goal should be the decriminalisation of gay sexual activity altogether.[40]

Human Rights Watch (HRW) praised the transitional government on various steps it had taken for legal reform, including the repealing of the public order law and the apostasy law, the criminalisation of FGM, and the approval of draft laws establishing commissions to work on human rights and transitional justice reforms, but urged it to accelerate its pace of legal and institutional reform and to better consult with civil society groups on new laws before passing them.[35]

The United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF), having earlier scrapped Sudan from the list of 'countries of particular concern' (where it had been in 2000–2019) due to its initial reforms, applauded in particular the new reforms relating to women's rights and the apostasy law on 15 July 2020. However, it urged Sudanese lawmakers to repeal the blasphemy law (Article 125 of the Sudanese Penal Code) as well, and to ensure 'that laws regulating hate speech comply with international human rights standards and do not impede freedom of religion or belief'.[34]

TMC–FFC Political Agreement and Constitutional Declaration

The TMC and FFC signed the written form of the Political Agreement on 17 July 2019[4] in front of witnesses representing the African Union, Ethiopia, and other international bodies.[5]

Elements of the agreement included:

- the creation of an 11-member Sovereignty Council with five military members and five civilians to be chosen by the two sides and a civilian to be agreed upon mutually;[18][5]

- a transition period of 3 years and 3 months, led by a TMC member for the first 21 months and a civilian member of the Sovereignty Council for the following 18 months;[18][5]

- the creation of a constitutional document for the transitional period;[5] Article 9.(a) of the 4 August Draft Constitutional Declaration defined the Sovereignty Council as the head of state of Sudan;[11]

- a Council of Ministers to be appointed mostly by the FFC, with the Sovereignty Council and its military members having a partial role in the decision;[18][5]

- a ban on members of the transitional period Sovereignty Council, Council of Ministers and state governors from being candidates in the first elections ending the transitional period;[5]

- a legislative council to be created within three months of the creation of the Sovereignty Council;[43][5]

- the creation of a Sudanese[43] "precise and transparent", independent investigation into the Khartoum massacre and "related" human rights violations incidents;[18][5]

- a six-month peace program for Darfur, Blue Nile and South Kordofan;[5]

- initiating a procedure for preparing a new constitution;[5]

- establishing transitional justice mechanisms.[5]

Democratic elections to determine leadership following the 39-month transition period were mentioned in the initial verbal agreement[3] and referred to in the written agreement.[5] Article 19 of the Draft Constitutional Declaration forbids "the chairman and members of the Sovereignty Council and ministers, governors of provinces, or heads of regions" from "[running] in the public elections" that follow the 39-month transition period.[11] Article 38.(c)(iv) of the declaration states that the chair and members of the Elections Commission are to be appointed by the Sovereignty Council in consultation with the Cabinet.[11]

Draft Constitutional Declaration

The 17 July written deal stated, as did the initial verbal deal,[22] that a constitutional agreement for the transition period was planned, and that preparations for a creating a new permanent constitution would be made during the transitional period.[5] Sudan's previous constitution was the 2005 Interim National Constitution.[44]

On 25 July, Mohamed El Hafiz of FFC legal committee stated FFC's requested changes to a draft of the constitutional declaration. FFC removed a draft article of the declaration that would have giving immunity from prosecution to TMC and Sovereign Council leaders. FFC required that reform of the security forces be carried out by a civilian, not military authority; that the Sovereign Council should only have ceremonial powers; that the Sovereign Council and Cabinet should together prepare laws pending creation of a Legislative Council; and that the Legislative Council should have full legislative powers, including the creation of land, law and election reform commissions. FFC's comments on the draft covered "85 articles and items".[45]

The Constitutional Declaration[10][11] was signed by Ahmed Rabee for FFC and deputy head of TMC, Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, on 4 August 2019, in the presence of Ethiopian and African Union mediators. Full ratification was planned for 17 August 2019.[12]

Transitional Sovereignty Council

The 11-member Sovereignty Council is defined by Article 9.(a) of the 4 August Draft Constitutional Declaration as the head of state of Sudan.[11] Planned membership of the Sovereignty Council includes military members Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo ("Hemetti"), Lieutenant-General Yasser al-Atta, and two other military members chosen by TMC;[13] five civilians chosen by FFC: Aisha Musa el-Said, Siddig Tower, Mohamed Elfaki Suleiman, Hassan Sheikh Idris and Mohammed Hassan al-Ta'ishi;[46][47] and a civilian, Raja Nicola, chosen by mutual agreement.[47] The Sovereignty Council is mostly male, with only two women members: Aisha Musa and Raja Nicola.[48]

Council of Ministers

The Political Agreement gave FFC the choice of the ministers of the transitional government,[18] with the sovereignty council holding the right to veto nominations,[43] apart from the defence and interior ministers, who are to be "selected" by military members of the Sovereignty Council and "appointed" by the prime minister.[5] The prime minister can "exceptionally nominate two party qualified members to fulfill ministerial positions."[5]

Chapter 5 (Article 14) of the Draft Constitutional Declaration defines the Transitional Cabinet in similar terms, and gives the Prime Minister the right to choose the other members of the cabinet from a list provided to him or her by FFC. The cabinet members are "confirmed by the Sovereignty Council".[11][10]

Article 16.(a) of the Draft Constitutional Declaration requires the Prime Minister and members of Cabinet to be "Sudanese by birth", at least 25 years old, a clean police record for "crimes of honour". Article 16.(b) excludes dual nationals from being a Minister of Defence, Interior, Foreign Affairs or Justice unless an exemption is agreed by the Sovereignty Council and the FFC for the position of Prime Minister, or by the Sovereignty Council and the Prime Minister for ministerial positions.[11]

Abdalla Hamdok, a Sudanese public administrator who served in numerous international administrative positions during the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries,[49] was nominated by the FFC as Prime Minister, with a formal appointment scheduled for 20 August 2019.[46]

Transitional Legislative Council

Chapter 7 of the 4 August Draft Constitutional Declaration defines plans for the Transitional Legislative Council.[11]

The transition deal (23.(4) of the Draft Constitutional Declaration[11][10]) sets the transitional Legislative Council to be formed three months after the transitional period starts,[43] after the sovereignty council and cabinet are determined.[18]

In the 17 July deal, FFC and TMC agreed to disagree on the proportions of membership of the Legislative Council. FFC "confirm[ed] its adherence" to selecting two thirds of the council's members and TMC "confirm[ed] its position on reviewing the legislative council membership percentages." The FFC and TMC agreed that their respective members of the Sovereignty Council would continue "discussion" on the issue.[5] In 23.(3) of the 4 August Draft Constitutional Declaration, 67% of the members are to be selected by the FFC and 33% by "other forces" who didn't sign the FFC declaration of January 2019.[11]

Article 23.(3) of the 4 August Draft Constitutional Declaration sets a minimum 40% quota for women membership of the Transitional Legislative Council.[11][10] Article 23.(1) sets the maximum membership to 300 and excludes membership by members of the National Congress that dominated under al-Bashir and of political forces that participated in the al-Bashir government.[11] Membership is open, under Article 25, to Sudanese nationals at least 21 years old, who "[possess] integrity and competence", have not been criminally convicted for "honour, trustworthiness, or financial responsibility", and can read and write.[11]

Judicial bodies

Chapter 8 of the 4 August Draft Constitutional Declaration replaces previous existing judicial bodies by a new Supreme Judicial Council and a Constitutional Court. It declares in Article 29.(2) that the "judicial authority" is independent from the Sovereignty Council, the Transitional Legislative Council and "the executive branch", with sufficient financial and administrative resources to be independent. In Article 30.(1) it defines the Constitutional Court to be independent and separate from the judicial authority.[11][10]

It was initially suggested by Khartoum Star and Sudan Daily that Nemat Abdullah Khair was to be sworn in as Chief Justice on 20 August[50] or 21 August 2019.[51] On 10 October 2019, her nomination was confirmed by decree.[52] Article 29.(3) states that the head of the judiciary is also the president of the Supreme Court and is "responsible for administering the judicial authority before the Supreme Judicial Council."[11][10]

Human rights

In the 4 August Draft Constitutional Declaration, Chapter 14 defines "Rights and freedoms". Article 41.(2) states that all international human rights agreements, pacts, and charters ratified by the Republic of Sudan are considered to be "an integral part" of the Draft Constitutional Declaration.[11]

Investigation

The deal was described on 5 July as including the creation of a "transparent and independent investigation" into the events that followed the 2019 Sudanese coup d'état, including the Khartoum massacre.[18] On 8 July, Associated Press described the investigation as "Sudanese".[43] The 17 July written political agreement stated that the investigation committee "may seek any African support if needed."[5]

The 4 August Draft Constitutional Declaration refers to the investigation in Article 7.(16) as an element of the "Mandate of the Transitional Period", defining the scope as "violations committed on 3 June 2019, and events and incidents where violations of the rights and dignity of civilian and military citizens were committed."[11] The investigation committee is to be created within a month of the Prime Minister's nomination, under an "order" that "guarantees that it will be independent and possess full powers to investigate and determine the timeframe for its activities".[11]

- Immunity

According to an anonymous military official present at pre-5 July negotiations and quoted by The Christian Science Monitor, US negotiators led by Donald E. Booth proposed that TMC members be guaranteed immunity from prosecution in the investigation. The military official stated, "The Americans demanded a deal as soon as possible. Their message was clear: power-sharing in return for guarantees that nobody from the council will be tried."[53] On 13 July, the FFC opposed 3 June Khartoum massacre suspects being members of the investigating committee.[22]

The 17 July written deal does not refer to immunity for TMC members.[5] On 25 July, Mohamed El Hafiz of the FFC legal committee stated its requests for changes to a draft of the constitutional declaration. This included the removal of a draft article that would have given immunity from prosecution to TMC and Sovereign Council leaders. El Hafiz said that neither absolute nor procedural immunity would be accepted for any leader.[45] On 31 July, TMC leader al-Burhan "confirmed that the members of the [junta] do not desire immunity".[54] On 1 August, the FFC accepted that Sovereign Council members could have "procedural immunity", defined to mean that Sovereign Council members would have immunity that could be lifted by a two-thirds supermajority vote of the legislative council.[55]

In the 4 August Draft Constitutional Declaration, Article 21 gives procedural immunity to members of the Sovereignty Council, the Cabinet, the Transitional Legislative Council, governors of provinces and heads of regions, with 21.(2) giving the Transitional Legislative Council the right to lift that immunity by a simple majority.[11][10]

- Creation

The Khartoum massacre investigation commission, headed by human rights lawyer Nabil Adib, was nominated on 20 October 2019 by Prime Minister Hamdok.[56]

Comprehensive peace

The 4 August Draft Constitutional Declaration lists "achieving a just and comprehensive peace, ending the war by addressing the roots of the Sudanese problem" as Article 7.(1), the first listed item in its "Mandate of the Transitional Period", and gives details in Chapter 15, Articles 67 and 58 of the document.[10][11] Article 67.(b) says that a peace agreement should be completed within six months of the signing of the Draft Constitutional Declaration. Article 67.(c) requires women to participate in all levels of the peace procedure and for United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 to be applied, and legal establishment of women's rights is covered in Article 67.(d). Other mechanisms for implementing the comprehensive peace process are listed in Articles 67.(e) (stopping hostilities, opening humanitarian assistance corridors, prisoner releases and exchanges), 67.(f) (amnesties for political leaders and members of armed opposition movements), and 67.(g) (accountability for crimes against humanity and war crimes and trials in national and international courts).[10] Article 68 lists 13 "essential issues for peace negotiations".[10]

On 31 August 2020, a peace agreement was signed in Juba, South Sudan, between Sudanese authorities and rebel factions to end armed hostilities.[57] Under the terms of the agreement, the factions that signed will be entitled to five ministers in the transitional cabinet and a quarter of seats in the transitional legislature. At a regional level, signatories will be entitled to 40% of the seats on transitional legislatures of their home states.[58] A final agreement was reached in early September. This agreement stated that 'Sudan is a multi-racial, multi-ethnic, multi-religious and multi-cultural society. Full recognition and accommodation of these diversities must be affirmed. (...) The state shall not establish an official religion. No citizen shall be discriminated against based on their religion.'[41]

Protests during 2019–2021

Protests continued during the creation of the transitionary period institutions, on issues that included the nomination of a new Chief Justice of Sudan and Attorney-General,[59] killings of civilians by the Rapid Support Forces (RSF),[60][61] the toxic effects of cyanide and mercury from gold mining in Northern state and South Kordofan,[62] protests against a state governor in el-Gadarif and against show trials of Sudanese Professionals Association (SPA) coordinators,[63] and for officials of the previous government to be dismissed in Red Sea and White Nile.[63]

Foreign influence on the transition

A group of four states, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom and the United States, named the QUAD for Sudan was formed in 2021[64] to facilitate mediation and talks along with the United Nations and the African Union. Saudi Arabia and the UAE wish to limit Islamist influence and the UK and the U.S. wish to limit Russian influence in the country.[65][66] The Quad claimed to have supported a transition to a democratic civilian-led government.[67][68]

The Trump administration tried to convince the transitional government to normalise Israel–Sudan relations by concluding a formal peace deal. It also offered to remove Sudan from its list of state sponsors of terrorism in return for 335 million US dollars in compensation to families of victims of the 1998 United States embassy bombings by al-Qaida, which the US government alleged the previous Sudanese regime played a role in. For the Sudanese transitional government, it was important to receive financial aid and open up trade opportunities in the midst of several ongoing crises, including decades of economic mismanagement under Bashir's regime, an unfinished internal peace process, recent political upheaval and the COVID-19 pandemic, leaving millions of Sudanese in hardship as food and fuel prices had soared. Therefore, in mid-October 2020, it agreed to pay the compensation and distanced itself from the pro-terrorist activities of the Bashir regime in order to lift the anti-terrorist sanctions imposed in 1993 and obtain access to foreign loans and recover the economy. Separately, Sudan had already been conducting negotiations for peace with Israel, and by mid-October had agreed to allow flights to Israel to overfly its territory.[69][70]

On the 100th day of the war in Sudan, clashes continue between the army and Rapid Support Forces, resulting in over 3 million people displaced and 1,136 deaths.The main civilian coalition, Forces of Freedom and Change, seeks resolution through a meeting in Egypt on 23 July 2023.[71]

2021 coup and aftermath

On 25 October 2021, the Sudanese military, led by General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, took control of the government in a military coup. At least five senior government figures were initially detained.[72] Civilian Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok refused to declare support for the coup and on 25 October called for popular resistance; he was moved to house arrest on 26 October. Civilian groups including the Sudanese Professionals Association and Forces of Freedom and Change called for civil disobedience and refusal to cooperate with the coup organisers. On 21 November 2021, al-Burhan freed prime minister Abdalla Hamdok from house arrest and the two signed a deal that re-instated Hamdok as prime minister and promised to release political prisoners.[73] Hamdok resigned on 2 January 2022 amid continuing protests.

The African Union suspended Sudan's membership, and the U.S. and European Union froze development assistance for Sudan’s transition. International Monetary Fund and World Bank aid halted, and Sudan's economy continued to decline.[74]

By April 2022, it was unclear whether the Sudanese transition to democracy would continue, as the military government was strengthening its ties with Russia, including after the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine started on 24 February 2022. While in the six months following the coup, Sudanese civilians had been taking to the streets on a daily basis, calling for a civil government and chanting "Military, go back to the barracks", negotiations between the military leadership and the United Nations Integrated Transition Assistance Mission Sudan (UNITAMS) led by Volker Perthes had become strained.[75]

December 2022 framework agreement

On 5 December 2022, representatives of 40 civilian groups, including an FFC representative, and military leaders al-Burhan and Hemetti, signed a new framework agreement for the transition to a civilian government.[76][77][78] The agreement, most of which was previously included in the 2020 Juba deal, committed the military to appoint a civilian government, including a civilian prime minister.[79] Following the appointment of the transitional government, a new two-year transition would then begin, concluding with elections. The deal set no date for a final agreement and left some of the controversial issues for future negotiations, leading to protests[80] by the Sudanese resistance committees.[76]

A "Final Agreement" was scheduled to be signed on 6 April 2023. On 6 April, Shehab Ibrahim of the FFC-CC (FFC-Central Council) stated that an "important breakthrough" in negotiations between civilian and military groups had been made and that new dates for signing the Final Agreement were being negotiated. On the same day, FFC-DB (FFC-Democratic Block), which had not signed the December 2022 "Framework Agreement", reported progress in negotiating fractions of power-sharing in the Juba Peace Agreement.[81]

Analysis

In March 2023, diplomat Rosalind Marsden described the December 2022 framework agreement as "a major step to reversing the damage" of the October 2021 coup. Marsden described the role of the Sudanese resistance committees as having been a key factor that convinced the military that their coup had failed. She stated that possible spoilers to the democratic transition were Popular Defence Forces linked to the National Islamic Front of the former al-Bashir government, recreated under new names. Marsden stated that supporters of the former al-Bashir government were using online social media to upset the Framework Agreement and to create division between the SAF and the RSF.[77]

2023 conflict

On 15 April 2023, the transition was interrupted again when the Rapid Support Forces launched attacks on government positions. As of 15 April 2023, RSF and al-Burhan both claimed control of government sites; fighting continued.[82]

See also

References

- "FACTBOX – Sudan's President Omar Hassan al-Bashir". Reuters. 14 July 2008. Retrieved 16 July 2008.

- "Sudan's Ibn Auf steps down as head of military council". Al Jazeera. Retrieved April 15, 2019.

- Kirby, Jen (2019-07-06). "Sudan's military and civilian opposition have reached a power-sharing deal". Vox. Archived from the original on 2019-07-05. Retrieved 2019-07-06.

- "Int'l community applauds Sudan political agreement". Radio Dabanga. 2019-07-18. Archived from the original on 2019-07-18. Retrieved 2019-07-18.

- FFC; TMC; Idris, Insaf (2019-07-17). "Political Agreement on establishing the structures and institutions of the transitional period between the Transitional Military Council and the Declaration of Freedom and Change Forces" (PDF). Radio Dabanga. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-07-18. Retrieved 2019-07-18.

- "Darfur displaced reject opposition - junta agreement". Radio Dabanga. 2019-07-12. Archived from the original on 2019-07-14. Retrieved 2019-07-20.

- "Sudan rebels reject junta-opposition political agreement". Radio Dabanga. 2019-07-18. Archived from the original on 2019-07-18. Retrieved 2019-07-20.

- "Sudan opposition: Political accord gives all power to junta". Radio Dabanga. 2019-07-20. Archived from the original on 2019-07-20. Retrieved 2019-07-20.

- "Sudanese Journalists Network criticises junta-opposition deal". Radio Dabanga. 2019-07-29. Archived from the original on 2019-07-20. Retrieved 2019-07-20.

- FFC; TMC (2019-08-04). "(الدستوري Declaration (العربية))" [(Constitutional Declaration)] (PDF). raisethevoices.org (in Arabic). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-08-05. Retrieved 2019-08-05.

- FFC; TMC; IDEA; Reeves, Eric (2019-08-10). "Sudan: Draft Constitutional Charter for the 2019 Transitional Period". sudanreeves.org. Archived from the original on 2019-08-10. Retrieved 2019-08-10.

- "Sudan Constitutional Declaration signed – Sovereign Council to be announced in two weeks". Radio Dabanga. 2019-08-04. Archived from the original on 2019-08-04. Retrieved 2019-08-04.

- "Sudan protest leaders, military sign transitional government deal". Al Jazeera English. 2019-08-17. Archived from the original on 2019-08-17. Retrieved 2019-08-17.

- "The Sudan Elections". The Spectator. 1948-11-26. Archived from the original on 2019-07-13. Retrieved 2019-07-13.

- Dolf Sternberger, Bernhard Vogel, Dieter Nohlen & Klaus Landfried (1978) Die Wahl der Parlamente: Band II: Afrika, Zweiter Halbband, p1954

- "Sudan generals, protesters reach landmark deal". Middle East Online. 2019-07-05. Archived from the original on 2019-07-08. Retrieved 2019-07-09.

- "Military junta and Alliance for Freedom and Change reach agreement on transitional period in Sudan". Radio Dabanga. 2019-07-05. Archived from the original on 2019-07-09. Retrieved 2019-07-09.

- "'Our revolution won': Sudan's opposition lauds deal with military". Al Jazeera English. 5 July 2019. Archived from the original on 2 April 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- "Minnawi, al Nur reject agreement on transitional rule in Sudan". Sudan Tribune. 2019-07-07. Archived from the original on 2019-07-06. Retrieved 2019-07-07.

- "Sudanese celebrate agreement between junta and opposition". Radio Dabanga. 2019-07-07. Archived from the original on 2019-07-07. Retrieved 2019-07-07.

- "FFC, SRF delegations arrive in Addis Ababa for talks on transition in Sudan". Sudan Tribune. 2019-07-09. Archived from the original on 2019-07-09. Retrieved 2019-07-09.

- "Demonstrators in Sudan demand justice for army crackdown victims". Al Jazeera English. 2019-07-13. Archived from the original on 2019-07-13. Retrieved 2019-07-13.

- "Darfur displaced denounce Constitutional Declaration". Radio Dabanga. 2019-08-06. Archived from the original on 2020-08-31. Retrieved 2019-08-08.

- "Minawi: Sudan Constitutional Declaration 'ignores Addis Ababa agreement'". Radio Dabanga. 2019-08-07. Archived from the original on 2021-05-22. Retrieved 2019-08-08.

- Political Agreement on establishing the structures and institutions of the transitional period between the Transitional Military Council and the Declaration of Freedom and Change Forces. 17 July 2019. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - "In The Name of God The Compassionate the Merciful. The Penal Code 1991" (PDF). European Country of Origin Information Network. Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation (ACCORD). 20 February 1991. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- "Sudan's new law on rape and sexual harassment One step forward, two steps back?" (PDF). African Centre for Justice and Peace Studies. 8 March 2016. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- "Draft Constitutional Charterfor the 2019 Transitional Period". Cyrilla. Transitional Military Council & Forces of Freedom and Change. 4 August 2019. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- Zeinab Mohammed Salih & Jason Burke (29 November 2019). "Sudan 'on path to democracy' as ex-ruling party is dissolved". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- James Copnall (29 November 2019). "Sudan crisis: Women praise end of strict public order law". BBC News. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- Kaamil Ahmed (16 July 2020). "'Thank you, our glorious revolution': activists react as Sudan ditches Islamist laws". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- "Sudan dissolves National Congress Party, repeals Public Order Bill". Radio Dabanga. 29 November 2019. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- Declan Walsh (30 April 2020). "In a Victory for Women in Sudan, Female Genital Mutilation Is Outlawed". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- "USCIRF Applauds Sudan's Repeal of Apostasy Law through Passage of New Fundamental Rights and Freedoms Act". United States Commission on International Religious Freedom. 15 July 2020. Archived from the original on 16 July 2020. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- "Sudan abolishes strict Islamic legislation". Radio Dabanga. 13 July 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- "New law abolishes apostasy, allows alcohol drinking for non-Muslim". Sudan Tribue. 11 July 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- "Sudan officially promulgates law ensuring women freedom". Sudan Tribue. 10 July 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- "Sudan scraps apostasy law and alcohol ban for non-Muslims". BBC News. 12 July 2020. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- "Sudan Justice Minister clarifies repeal of strict laws". Radio Dabanga. 13 July 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- Ban Barkawi, Rachel Savage (16 July 2020). "'Great first step' as Sudan lifts death penalty and flogging for gay sex". Reuters. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- Michael Atit (4 September 2020). "Sudan's Government Agrees to Separate Religion and State". Voice of America. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- Nabeel Biajo (2 September 2020). "Sudan Holdout Group: Peace Deal Fails to Address Conflict's Root Causes". Voice of America. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- "Sudan's military council to be dissolved in transition deal". WTOP-FM. AP. 2019-07-08. Archived from the original on 2019-07-08. Retrieved 2019-07-08.

- "Interim National Constitution of the Republic of Sudan, 2005" (PDF). Refworld.org. UNHCR. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-07-08. Retrieved 2014-06-01.

- "Sudan's pro-democracy movement concludes Constitutional Declaration draft". Radio Dabanga. 2019-07-28. Archived from the original on 2019-07-28. Retrieved 2019-07-29.

- "Sudan opposition coalition appoints five civilian members of sovereign council". Thomson Reuters. 2019-08-18. Archived from the original on 2019-08-18. Retrieved 2019-08-18.

- "FFC finally agree on nominees for Sudan's Sovereign Council". Sudan Tribune. 2019-08-20. Archived from the original on 2019-08-20. Retrieved 2019-08-20.

- "Sudanese Women's Union protests FFC nominees". Radio Dabanga. 2019-08-18. Archived from the original on 2019-08-19. Retrieved 2019-08-19.

- "Abdalla Hamdok – Deputy Executive Secretary – United Nations Economic Commission for Africa". United Nations Industrial Development Organization. 2018. Archived from the original on 2019-08-13. Retrieved 2019-08-13.

- "In a historic event .. The appointment of a woman as chief of justice in Sudan". Khartoum Star. 2019-08-21. Archived from the original on 2019-08-24. Retrieved 2019-08-25.

- "TMC and FFC pick new Chief Justice". Sudan Daily. 2019-08-21. Archived from the original on 2019-08-24. Retrieved 2019-08-25.

- "Sudan appoints its first woman Chief Justice". Radio Dabanga. 2019-10-10. Archived from the original on 2019-10-10. Retrieved 2019-10-10.

- Magdy, Samy (2019-07-08). "Sudan: International pressure enabled power-sharing pact". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 2019-07-08. Retrieved 2019-07-08.

- "AU mediator: Sudan Constitutional Declaration nears completion". Radio Dabanga. 2019-08-01. Archived from the original on 2019-08-01. Retrieved 2019-08-01.

- "Four protesters 'killed by live ammunition' in Sudan's Omdurman". Al Jazeera English. 2019-08-01. Archived from the original on 2019-08-02. Retrieved 2019-08-02.

- Abdelaziz, Khalid (2019-10-21). "Tens of thousands rally against former ruling party in Sudan". Thomson Reuters. Archived from the original on 2019-10-21. Retrieved 2019-10-21.

- "Sudan signs peace deal with rebel groups from Darfur". Al Jazeera. 31 August 2020.

- "Sudan signs peace deal with key rebel groups, some hold out". Reuters. August 31, 2020 – via www.reuters.com.

- "Sudanese call for justice in first protest under Hamdok's cabinet". Sudan Tribune. 2019-09-13. Archived from the original on 2019-09-14. Retrieved 2019-09-14.

- "'Militia' shooting prompts mass demo in South Darfur". Radio Dabanga. 2019-09-17. Archived from the original on 2019-09-23. Retrieved 2019-09-23.

- "South Darfur demo damns demonstrator deaths". Radio Dabanga. 2019-09-18. Archived from the original on 2019-09-23. Retrieved 2019-09-23.

- "March against new gold mine in Northern State". Radio Dabanga. 2019-09-18. Archived from the original on 2019-09-23. Retrieved 2019-09-23.

- "Protests across Sudan address public dissatisfaction". Radio Dabanga. 2019-09-19. Archived from the original on 2019-09-23. Retrieved 2019-09-23.

- "'Quad for Sudan' Calls for Peace, Democracy After Coup, Protests". Voice of America. 3 November 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- Fulton, Adam; Holmes, Oliver (25 April 2023). "Sudan conflict: why is there fighting and what is at stake in the region?". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- Brooke-Holland, Louisa (25 April 2023). "UK response to unrest in Sudan" (PDF). House of Commons Library. UK Parliament. CBP-9778. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- "Joint statement by the QUAD for Sudan, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, the United States of America and the United Kingdom, on the developments in Sudan". U.S. Department of State. 3 November 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- "Quad and Troika Statement at Start of National/Federal Workshop on Transitional Justice". U.S. Department of State. 17 March 2023. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- "Sudan discusses Arab-Israeli peace and terrorism list with U.S.: statement". Reuters. 23 September 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- Jason Burke and Oliver Holmes (19 October 2020). "US removes Sudan from terrorism blacklist in return for $335m". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- Abdelaziz, Khalid (2023-07-23). "Sudan war enters 100th day as mediation attempts fail". Reuters. Retrieved 2023-07-24.

- "Sudan's PM and other leaders detained in apparent coup attempt", The Guardian, Sudan, 25 October 2021, archived from the original on 25 October 2021, retrieved 25 October 2021

- "Sudan's Hamdok reinstated as PM after political agreement signed". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2021-11-21.

- "A Critical Window to Bolster Sudan's Next Government". International Crisis Group. 23 January 2023. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- (www.dw.com), Deutsche Welle. "Sudan: Cold shoulder for UN, warm embrace for Russia | DW | 21.04.2022". DW.COM. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- "Sudan's long-awaited framework agreement signed between military and civilian bodies". Radio Dabanga. 6 December 2022. Wikidata Q117787748. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023.

- Rosalind Marsden (28 March 2023), A critical juncture for Sudan's democratic transition, Chatham House, Wikidata Q117788038, archived from the original on 28 March 2023

- "Sudan's generals, pro-democracy group ink deal to end crisis". AP NEWS. 2022-12-05. Retrieved 2023-02-24.

- Ali, Wasil (2022-12-07). "Skepticism as Sudan's military and pro-democracy group ink deal". Axios. Retrieved 2023-02-24.

- Abdelaziz, Khalid; Eltahir, Nafisa (2022-12-05). "Sudan generals and parties sign outline deal, protesters cry foul". Reuters. Retrieved 2023-02-24.

- "Breakthrough on security reform, rebels demand more power, revolutionary forces call for unity". Radio Dabanga. 6 April 2023. Wikidata Q117787817. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023.

- "At least 25 killed, 183 injured in ongoing clashes across Sudan as paramilitary group claims control of presidential palace". CNN. 15 April 2023. Retrieved 15 April 2023.