Islamism in Sudan

The Islamist movement in Sudan started in universities and high schools as early as the 1940s under the influence of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood.[1] The Islamic Liberation Movement, a precursor of the Sudanese Muslim Brotherhood, began in 1949.[1] Hassan Al-Turabi then took control of it under the name of the Sudanese Muslim Brotherhood.[1] In 1964, he became secretary-general of the Islamic Charter Front (ICF), an activist movement that served as the political arm of the Muslim Brotherhood.[1] Other Islamist groups in Sudan included the Front of the Islamic Pact and the Party of the Islamic Bloc.[1][2]

As of 2011, Al-Turabi, who created the Islamist Popular Congress Party, had been the leader of Islamists in Sudan for the last half century.[1] Al-Turabi's philosophy drew selectively from Sudanese, Islamic, and Western political thought to fashion an ideology for the pursuit of power.[1] Al-Turabi supported sharia and the concept of an Islamic state, but his vision was not Wahhabi or Salafi.[1] He appreciated that the majority of Sudanese followed Sufi Islam, which he set out to change with new ideas.[1] He did not extend legitimacy to Sufis, Mahdists, and clerics, whom he saw as incapable of addressing the challenges of modern life.[1] One of the strengths of his vision was to consider different trends in Islam.[1] Although the political base for his ideas was probably relatively small, he had an important influence on Sudanese politics and religion.[1]

Following the 2018–2019 Sudanese Revolution and 2019 coup, the future of Islamism in Sudan was in question.[3][4]

Early years

Following its integration with Khedivate of Egypt, modern Sudan experienced an early emergence of politicised religious movements. This phenomenon became evident in 1843 when Muhammad bin Abdullah bin Fahal, known as Muhammad Ahmad al-Mahdi, initiated the Mahdist revolution against the rule of Turkish-Egyptian authorities in Sudan. Al-Mahdi successfully liberated Khartoum and defeated General Charles Gordon, the military leader under Khedive Ismail's jurisdiction. This led to the establishment of the Mahdist state in 1885. Although the Mahdist state was eventually overpowered by British forces in Egypt in 1899, the movement's influence endured, and its adherents were referred to as "Ansar." This continued until Abd al-Rahman al-Mahdi founded the "Umma" Party in February 1945, aiming to advocate for Sudan's independence from the joint control of Egypt and Britain.[5]

Conversely, during Egyptian-Turkish rule in Sudan, support was extended to the "Khatmiyyah," established by Muhammad Othman al-Mirghani al-Khitmi in 1817, coinciding with the arrival of Egyptian-Turkish authority. This order retained backing during the British occupation, serving as a local rival to the Ansar movement. In 1943, Ali Al-Mirghani, the leader of the Khatmiyyah, endorsed the "brothers" movement initiated by Ismail Al-Azhari, which called for Sudan's autonomy within a united framework with Egypt. This movement later transformed into the "National Unionist Party (NUP)." Subsequently, the Khatmiyyah splintered in June 1956, forming "The People's Democratic Party," which later reunited with the Democratic Unionist Party in December 1967.[5]

Muslim Brotherhood in Sudan (1954–1964)

In 1946, the Muslim Brotherhood's activities began in Sudan through Jamal al-Din al-Sanhuri, a Sudanese closely associated with Hassan al-Banna. He returned to Sudan to establish the group's presence. In 1948, during a ceremony in Egypt marking the Brotherhood's 20th anniversary, Hassan al-Banna announced the growth of the organisation to a thousand branches in Egypt and fifty in Sudan. However, before Ali Talib Allah was appointed as the observer general of the Sudanese Brotherhood in 1948, British occupation authorities denied the movement permission to operate there.[5]

In 1949, an Islamist movement emerged at Gordon Memorial College (later University of Khartoum) with the goal of countering communist dominance among students. This movement, named the "Islamic Liberation Movement," was led by Muhammad Youssef Muhammad and Babiker Karrar. It embraced "Islamic socialism" and distanced itself from the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood. Despite this, ideological similarities between the movement and Sudanese Brotherhood followers led to conflicts between their leaderships. These disputes were resolved through the Eid Conference of August 1954, resulting in the adoption of the name "The Muslim Brotherhood" and the election of Muhammad Khair Abd al-Qadir as its secretary-general. However, this decision caused divisions, leading the Babiker Karrar group to form the "Islamic Group," which later established the "Islamic Socialist Party." Meanwhile, Ali Talib Allah's faction, supported by Hassan al-Banna, contested legitimacy. The Egyptian General Center intervened, electing Al-Rashid Al-Taher Bakr, a lawyer from the Talib Allah group, as the general observer for the Sudanese Brotherhood.[5]

The Muslim Brotherhood's political engagement intensified in December 1955, organising a conference involving religious wings of Ansar and Khatmiyya, along with various Islamic associations. This assembly established the "Islamic Front for the Constitution," advocating for an Islamic constitution post-independence, emphasising trustworthiness among Muslims.[5]

In 1959, Al-Rashid Al-Taher was arrested for his alleged involvement in a coup against General Ibrahim Abboud's military regime. Despite his five-year prison sentence, the Brotherhood denied any involvement in the coup. Al-Rashid's removal from leadership caused a decline in the group's activities.[5]

Meanwhile, the "Islamic Group" formed after 1954 and the "Islamic Socialist Party," established in 1964, faced limited success. The ideas of Babikr Karar, rooted in reconciling Islam, socialism, and Arab nationalism, did not gain significant attention. After the Numeiri coup, Babikr Karar, like many political elites in Sudan, relocated to Libya following the September Al-Fateh Revolution. His later attempts to rejuvenate the experiment, alongside Nasser Al-Sayyid and Mirghani Al-Nasri, achieved limited success compared to their initial mentor.[5]

Islamic Charter Front (1964–1969)

Hassan al-Turabi, a constitutional law professor at the University of Khartoum who had recently returned from studies in Paris, gained prominence during the October 1964 revolution that toppled General Ibrahim Abboud's regime. Subsequently, he established the "Islamic Charter Front," uniting the Muslim Brotherhood, Ansar al-Sunnah, and the Tijaniya under a common goal—the pursuit of an Islamic constitution. The Front secured seven seats in the 1965 elections but faced a reduced share in the 1968 elections.[5]

Al-Turabi effectively broadened the Front's membership and transformed it into a pressure group that compelled the Constituent Assembly to outlaw the Sudanese Communist Party in November 1965. It emerged as Sudan's third most influential party after the Umma and Democratic Unionist Parties. Following his election as Secretary-General in April 1969, a move that troubled the more education-oriented faction due to his frontline political approach, some members split from the group, including Muhammad Saleh Omar, Jaafar Sheikh Idris, and Ali Jawish. However, this division remained dormant due to Nimeiri's coup and the subsequent anti-Islamist Mayo regime.[5]

After a failed coup attempt in June 1976 orchestrated by Brigadier General Muhammad Nour Saad and backed by major parties forming the "National Front" opposing Numeiri's rule, Numeiri shifted toward Islamists, aiming for "national reconciliation." This led to the integration of Al-Sadiq al-Mahdi and Al-Turabi into the Sudanese Socialist Union's political bureau. Although the reconciliation with Al-Sadiq al-Mahdi quickly soured, Al-Turabi assumed the role of Attorney General in 1979.[5]

Al-Turabi believed that aligning with the system, penetrating the socialist union, and rebuilding the fractured organization after the coup and exile was a strategic choice during the "Empowerment Period." He also capitalized on Nimeiri's crackdown on the communists after their 1971 coup attempt.[5]

In 1979, the ongoing disagreement between the Sudanese Brotherhood and the parent organization resurfaced. Al-Turabi declined allegiance to the international group, and a split occurred, with Sheikh Sadiq and his followers aligning with him. Pontiff Youssef Nour al-Daim took charge of the Sudanese Brotherhood since 1969, although it remained a minor faction with limited influence. Al-Turabi designated his wing the "Sudanese Islamic Movement."[5]

Al-Turabi's influence peaked when Nimeiri enforced Sharia laws in September 1983. Al-Turabi supported this move, differing from Al-Sadiq al-Mahdi's dissenting view. Al-Turabi and his allies within the regime also opposed self-rule in the south, a secular constitution, and non-Islamic cultural acceptance. One condition for national reconciliation was re-evaluating the 1972 Addis Ababa Agreement that granted the south self-governance, reflecting a failure to accommodate minority rights and leverage Islam's rejection of racism.[5]

Sharia laws

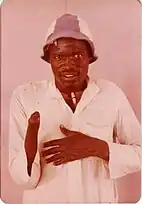

Some of the victims of the September 1983 Laws after amputation according to Sharia law taken by Peter Anton von Arnim in 1986In September 1983, President Jaafar Nimeiri introduced sharia law in Sudan, known as September 1983 laws, symbolically disposing of alcohol and implementing hudud punishments like public amputations. The Islamic economy followed in early 1984, eliminating interest and instituting zakat. Nimeiri declared himself the imam of the Sudanese Umma in 1984.[6]

Nimeiri's attempt at implementing an "Islamic path" in Sudan from 1977 to 1985, including aligning with religious factions, ultimately failed. His transition from nationalist leftist ideologies to strict Islam was detailed in his books "Al-Nahj al-Islami limadha?" and "Al-Nahj al-Islami kayfa?" The connection between Islamic revival and reconciling with opponents of the 1969 revolution coincided with the rise of militant Islam in other parts of the world. Nimeiri's association with the Abu Qurun Sufi order influenced his shift towards Islam, leading him to appoint followers of the order into significant roles. The process of legislating the "Islamic path" began in 1983, culminating in the enactment of various orders and acts to implement sharia law and other Islamic principles.[6]

Nimeiri's establishment of the Islamic state in Sudan was outlined in his speech at a 1984 Islamic conference. He justified the implementation of the sharia due to a rising crime rate. He claimed a reduction of crime by over 40% within a year due to the new punishments. Nimeiri attributed Sudan's economic success to the zakat and taxation act, outlining its benefits for the poor and non-Muslims. His association with the Abu Qurun Sufi order and his self-proclaimed position as imam led to his belief that he alone could interpret laws in line with the sharia. However, his economic policies, including Islamic banking, led to severe economic issues. Nimeiri's collaboration with the Muslim Brotherhood and the Ansar aimed to end sectarian divisions and implement the sharia. The Ansar, despite initial collaboration, criticized Nimeiri's implementation as un-Islamic and corrupt.[6]

Nimeiri's Islamic phase resulted in renewed conflict in Southern Sudan in 1983, marking the end of the Addis Ababa Agreement of 1972, which had granted regional autonomy and recognized the diverse nature of Sudanese society. The agreement ensured equality regardless of race or religion and allowed for separate personal laws for non-Muslims. However, hostilities escalated due to oil discovery, dissolution of the Southern Regional Assembly, and decentralization efforts. Despite this, the Islamic laws implemented by Nimeiri exacerbated the situation. The political landscape shifted with Nimeiri's removal in 1985, leading to the emergence of numerous political parties. The National Islamic Front (NIF), Ansar, and Khatmiyya Sufi order (DUP) played crucial roles in Sudan's politics. Hasan al-Turabi and the NIF consistently supported the Islamic laws and resisted changes.[6]

Another Islamic movement in Sudan was the Republican Brotherhood, founded by Mahmoud Muhammad Taha. This movement embraced the concept of Islam having two messages and abandoned numerous Islamic practices. It advocated for peaceful coexistence with Israel, gender equality, criticised Wahhabism, called for freedoms and refraining from implementing Islamic criminal punishments, and championed a federal social democratic government. Taha strongly opposed the ban on the Sudanese Communist Party and condemned the decision as a distortion of democracy, even though he wasn't a communist. He was sentenced to apostasy in 1968 and again in 1984, leading to his execution in January 1985 under the September laws, despite his strong opposition. This event significantly fuelled public and international discontent.[5]

National Islamic Front (1985–1989)

Following the fall of Nimeiri's regime, al-Turabi and his associates established the "National Islamic Front." This newly formed group participated in the Constituent Assembly elections and secured the third position, amassing 54 seats. This achievement positioned them as the leading opposition force. Al-Turabi once again excelled in playing the role of a influential opposition party, effectively thwarting Sadiq al-Mahdi's endeavour—head of the government and the parliamentary majority—to suspend the contentious September laws and push forward peace negotiations with the southern region.[5]

In response to mounting pressures, Al-Sadiq Al-Mahdi was compelled to forge an alliance with the National Islamic Front on 15 May 1988. This alliance resulted in the establishment of the Government of National Accord, in which al-Turabi assumed the role of Minister of Justice with the task of reshaping Sharia laws. Meanwhile, both parties—the nation and the front—confronted a peace agreement brokered by Muhammad Othman al-Mirghani, leader of the Democratic Unionist Party and head of the Sovereignty Council, with the "Sudan People's Liberation Army." This rebel movement, led by John Garang, was the primary opposition force in the south and was engaged in a fierce conflict with the Sudanese army.[5] Meanwhile, Sadiq al-Mahdi, leader of the Ansar and prime minister during Sudan's third democratic episode, initially opposed the Islamic laws he later supported. He proposed a vision of a fully Arabized and Islamized southern Sudan, aiming for unity but differing from his earlier, more liberal views. The failure to address Sudan's issues led to the military coup by Omar al-Bashir in 1989, further entrenching Islamic principles.[6]

In light of the escalating challenges concerning southern peace negotiations and the September Laws, Sadiq al-Mahdi was compelled to re-establish the Government of National Accord in February 1988. The Front's influence within the coalition expanded, resulting in al-Turabi assuming the position of Foreign Minister. This move raised concerns in Egypt, which regarded al-Turabi as an extremist Islamist figure. In February 1989, the army issued a memorandum to the government, urging the approval of the peace agreement brokered by Al-Mirghani and the resolution of the worsening economic situation. The National Islamic Front perceived this memorandum as directed against them, given their strong opposition to peace negotiations with the southern region.[5]

Kizan Era (1989–1999)

On 30 June 1989, Brigadier General Omar al-Bashir executed a coup against the existing democratic government. In the coup's proclamation, labelled the "National Rescue Revolution," al-Bashir cited the economic shortcomings of the Mahdi administration and its inability to establish relations with Central Africa as reasons for the coup. This reasoning was met with scepticism. Subsequently, al-Bashir detained numerous political leaders, including Hassan al-Turabi. Egypt expressed approval of this move.[5]

In a remarkable turn of events in December, the officers of the Revolutionary Command Council for National Salvation publicly pledged loyalty to Hassan al-Turabi, who they had previously arrested. Together with the leaders of the National Islamic Front, al-Turabi established the "Council of Defenders of the Revolution," also known as the "Committee of Forty," which took on effective political leadership.[5]

The process of solidifying and Islamising the new regime unfolded using familiar tools of authoritarian rule. A political security apparatus named the "Internal Security" was established, led by Colonel (later Major General) Bakri Hassan Saleh. This body conducted arrests and engaged in torture of those suspected of disloyalty to the regime. Its notorious detention facilities, known as "ghost houses," gained notoriety. Intellectuals such as Muhammad Omar al-Bashir, a distinguished historian and University of Khartoum professor, were among those dismissed, detained, and subjected to torture.[5]

The regime introduced a new penal code in December 1991, which seemed even more stringent than the September laws. The establishment of the "People's Police," akin to Saudi Arabia's Committee for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice, occurred. Fundamental public freedoms eroded, including the right to form unions, and political parties were abolished.

Interestingly, prior to these events, both al-Turabi and his wife, Wissal Al-Mahdi (the sister of his rival Al-Sadiq Al-Mahdi), held open jurisprudential positions that sparked criticism from religious scholars. Al-Turabi had also advocated for constitutional rule, yet this stance did not align with the social policies of the Salvation regime that he helped establish.[5]

Al-Turabi also made efforts in international realms, attempting to establish an "Islamic International" and reconcile with leftist and nationalist groups to counter imperialism. In April 1991, he founded the "Arab and Islamic People's Conference," attended by representatives from various countries, including the Philippines' Abu Sayyaf group and the Muslim Brotherhood. Later that year, Osama bin Laden relocated to Khartoum and was welcomed by al-Turabi, who even facilitated bin Laden's marriage to a relative. Training camps for armed Islamic groups from different nations were established in Sudan, and al-Turabi attempted mediation between Hamas and the Palestine Liberation Organization.[5]

Al-Turabi's involvement with the Egyptian Islamic Jihad in a plot to assassinate Egyptian President Mohamed Hosni Mubarak in 1995 drew significant attention. Sanctions imposed by the United Nations on Sudan in 1996 isolated the country, causing Bin Laden to depart and al-Turabi's influence to wane. The extradition of leftist activist/terrorist Carlos the Jackal to France in 1994 also sparked discontent within the National Front itself toward al-Turabi.[5]

After a decade of tumultuous events, al-Bashir removed al-Turabi from the presidency of the National Council in 1999. Subsequently, al-Turabi was ousted from the General Secretariat of the National Congress Party. In response, al-Turabi established the "Popular Congress Party." Interestingly, he pragmatically signed a memorandum of understanding with the Sudan People's Liberation Movement, an erstwhile enemy. This eventually led to al-Turabi's imprisonment.[5]

During the internal power struggle between al-Bashir and al-Turabi, the core body of the Sudanese Islamic Movement aligned with al-Bashir. Prominent among them was Ali Othman Taha, a powerful Islamist figure who held the position of vice president from 1998 to 2013. During this period, the regime became highly militarised, and the Islamists, often mockingly referred to as "Kizans" (Sudanese Arabic for cups) due to al-Turabi's saying, "Religion is a sea, and we are its cup (kizan)".[5]

New Islamic Movements

Sheikh Sadiq Abdullah Abdul Majid continued to lead the Muslim Brotherhood's international organization branch, alongside Professor Youssef Nour Al-Daim. The group encountered a crisis in 1991 when the extremist Salafist and Wahhabi wing led by Sheikh Suleiman Abu Naro won elections. This resulted in the traditional wing rejecting the General Shura Council. Sheikh Abu Naro's faction separated into two groups: the "Reform Group," which eventually reunited with the main organization, and the "Sit-Into the Qur'an and Sunnah Movement," which leaned toward extremist Salafism and gradually edged closer to jihadist Salafism. Sheikh Abu Naro passed away in 2014, and Sheikh Omar Abdul Khaleq succeeded him, gaining prominence for declaring support for the Islamic State (ISIS).[5]

In 2012, Sheikh Ali Jawish was elected as the group's general observer in Sudan. Under Ali Jawish's leadership, a division emerged between two wings: the conservative traditional wing, led by Jawish, focused on maintaining ties with the mother organisation in Egypt after its challenges starting in 2013; and the political reform wing represented by the group's Shura Council. This division led Jawish to dissolve the Shura Council in June 2016 and postpone the General Conference for a year. The General Conference re-elected Jawish in March 2017 but dismissed him in December of the same year. Awadallah Hussein, a professor at Omdurman Islamic University's Faculty of Medicine, was chosen as the group's general observer. However, Jawish retained the title with international organisation support until his passing in December.[5]

After Turabi's overthrow, the Brotherhood participated in the Bashir regime's governments. Yet, the group joined the December 2018 protest, aligning closely with the Forces of Freedom and Change, although not being a formal member. Presently, the group wields limited popular, organisational, or cultural influence.[5]

Conversely, recent years have seen the emergence of smaller Islamic groups that either split from other movements or were founded by young Islamic intellectuals. Among these is the "Reform Now" movement led by Ghazi Salah al-Din, a former leader of the ruling National Congress Party who separated from the party in 2013. This movement leads the "National Front for Change" coalition, encompassing the Islamist-leaning East Party for Justice and Development, the Democratic Unionist Party, and other parties.[5]

The National Coordination Initiative for Change and Construction forms a coalition of moderate Islamists. This initiative includes the "National Change Initiative" headed by Ambassador Al-Shafi’ Ahmed Mohamed, a former Secretary-General of the ruling party. Almhabob Abdul Salam, a dedicated student of Hassan al-Turabi, broke away from the Popular Congress Party to establish the "Democratic Islamists" movement. Also, Muhammad Al-Majzoub, a political science professor at Al Neelain University with expertise in Islamic political thought, founded "The Initiative for the Transition towards Freedoms and Peaceful Deliberation."[5]

The "Reform and Renaissance Initiative (Tourists)" also signed the initiative, comprising from former fighters who fought against the "Sudan People’s Liberation Movement" in the south. They hold a critical stance toward the Bashir regime after secession, emphasising the need for Islamists to relinquish state power and prioritize social reform. This initiative is led by Fatah Al-Alim Abdel-Hay. Additionally, the "Future Now Initiative," led by Mustafa Idris, former president of the University of Khartoum and a former member of the Sudanese Islamic Movement, is part of this movement landscape.[5]

Further reading

- An-Na'im, Abdullahi Ahmed (1989). "Constitutionalism and Islamization in the Sudan". Africa Today. 36 (3/4): 11–28. ISSN 0001-9887.

- Noble-Frapin, Ben (2009). "The Role of Islam in Sudanese Politics: a Socio-Historical Perspective". Irish Studies in International Affairs. 20: 69–82. ISSN 0332-1460.

- Warburg, Gabriel R. (October 1985). "Islam and State in Numayri's Sudan". Africa. 55 (4): 400–413. doi:10.2307/1160174. ISSN 1750-0184.

- Fluehr-Lobban, Carolyn (1990). "Islamization in Sudan: A Critical Assessment". Middle East Journal. 44 (4): 610–623. ISSN 0026-3141.

References

- Shinn, David H. (2015). "Popular Congress Party" (PDF). In Berry, LaVerle (ed.). Sudan : a country study (5th ed.). Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. pp. 254–256. ISBN 978-0-8444-0750-0.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Zahid, Mohammed; Medley, Michael (2006). "Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt & Sudan". Review of African Political Economy. 33 (110): 693–708. ISSN 0305-6244. JSTOR 4007135.

- Assal, Munzoul A. M. (2019). "Sudan's popular uprising and the demise of Islamism". Chr. Michelsen Institute. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- Beaumont, Peter; Salih, Zeinab Mohammed (2 May 2019). "Sudan: what future for the country's Islamists?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- هدهود, محمود (15 April 2019). "تاريخ الحركة الإسلامية في السودان". إضاءات (in Arabic). Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- Warburg, Gabriel R. (1990). "The Sharia in Sudan: Implementation and Repercussions, 1983-1989". Middle East Journal. 44 (4): 624–637. ISSN 0026-3141. JSTOR 4328194.