Theodore Roosevelt

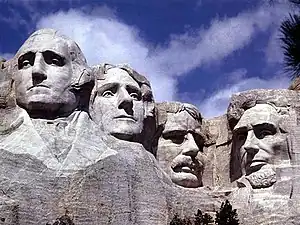

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (/ˈroʊzəvɛlt/ ROH-zə-velt;[lower-alpha 2] October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26th president of the United States from 1901 to 1909. He previously served as the 25th vice president under President William McKinley from March to September 1901 and as the 33rd governor of New York from 1899 to 1900. Assuming the presidency after McKinley's assassination, Roosevelt emerged as a leader of the Republican Party and became a driving force for anti-trust and Progressive policies.

Theodore Roosevelt | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Portrait by the Pach Brothers, c. 1904 | |

| 26th President of the United States | |

| In office September 14, 1901 – March 4, 1909 | |

| Vice President |

|

| Preceded by | William McKinley |

| Succeeded by | William Howard Taft |

| 25th Vice President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1901 – September 14, 1901 | |

| President | William McKinley |

| Preceded by | Garret Hobart |

| Succeeded by | Charles W. Fairbanks |

| 33rd Governor of New York | |

| In office January 1, 1899 – December 31, 1900 | |

| Lieutenant | Timothy L. Woodruff |

| Preceded by | Frank S. Black |

| Succeeded by | Benjamin Barker Odell Jr. |

| 5th Assistant Secretary of the Navy | |

| In office April 19, 1897 – May 10, 1898 | |

| President | William McKinley |

| Preceded by | William McAdoo |

| Succeeded by | Charles Herbert Allen |

| President of the New York City Board of Police Commissioners | |

| In office May 6, 1895 – April 19, 1897 | |

| Appointed by | William Lafayette Strong |

| Preceded by | James J. Martin |

| Succeeded by | Frank Moss |

| Commissioner of the United States Civil Service Commission | |

| In office May 7, 1889[1] – May 6, 1895 | |

| Appointed by | Benjamin Harrison |

| Preceded by | John H. Oberly[2] |

| Succeeded by | John B. Harlow[3] |

| Minority Leader of the New York State Assembly | |

| In office January 1, 1883 – December 31, 1883 | |

| Preceded by | Thomas G. Alvord |

| Succeeded by | Frank Rice |

| Member of the New York State Assembly from the 21st district | |

| In office January 1, 1882 – December 31, 1884 | |

| Preceded by | William J. Trimble |

| Succeeded by | Henry A. Barnum |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Theodore Roosevelt Jr. October 27, 1858 New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Died | January 6, 1919 (aged 60) Oyster Bay, New York, U.S. |

| Resting place | Youngs Memorial Cemetery, Oyster Bay |

| Political party | Republican (1880–1912, 1916–1919) |

| Other political affiliations | Progressive "Bull Moose" (1912–1916) |

| Spouses | |

| Children | |

| Parents | |

| Relatives | Roosevelt family |

| Alma mater | Harvard University (AB) Columbia University |

| Occupation |

|

| Civilian awards | Nobel Peace Prize (1906) |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | United States Army |

| Years of service |

|

| Rank | |

| Commands | 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry |

| Battles/wars | |

| Military awards | Medal of Honor (posthumous, 2001) |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

33rd Governor of New York

25th Vice President of the United States

26th President of the United States

First term

Second term

Post Presidency

|

||

A sickly child with debilitating asthma, he overcame his health problems as he grew by embracing a strenuous lifestyle. Roosevelt integrated his exuberant personality and a vast range of interests and achievements into a "cowboy" persona defined by robust masculinity. He was home-schooled and began a lifelong naturalist avocation before attending Harvard College. His book The Naval War of 1812 (1882) established his reputation as a learned historian and popular writer. Upon entering politics, Roosevelt became the leader of the reform faction of Republicans in New York's state legislature. His first wife and mother died on the same night, devastating him psychologically. He recuperated by buying and operating a cattle ranch in the Dakotas. Roosevelt served as Assistant Secretary of the Navy under President McKinley, and in 1898 helped plan the highly successful naval war against Spain. He resigned to help form and lead the Rough Riders, a unit that fought the Spanish Army in Cuba to great publicity. Returning a war hero, Roosevelt was elected governor of New York in 1898. The New York state party leadership disliked his ambitious agenda and convinced McKinley to choose him as his running mate in the 1900 election. Roosevelt campaigned vigorously and the McKinley–Roosevelt ticket won a landslide victory based on a platform of victory, peace, and prosperity.

Roosevelt assumed the presidency at age 42, and remains the youngest person to become president of the United States. As a leader of the progressive movement he championed his "Square Deal" domestic policies. It called for fairness for all citizens, breaking of bad trusts, regulation of railroads, and pure food and drugs. Roosevelt prioritized conservation and established national parks, forests, and monuments to preserve the nation's natural resources. In foreign policy, he focused on Central America, where he began construction of the Panama Canal. Roosevelt expanded the Navy and sent the Great White Fleet on a world tour to project American naval power. His successful efforts to broker the end of the Russo-Japanese War won him the 1906 Nobel Peace Prize, making him the first American to ever win a Nobel Prize. Roosevelt was elected to a full term in 1904 and promoted policies more to the left, despite growing opposition from Republican leaders. During his presidency, he groomed his close ally William Howard Taft to succeed him in the 1908 presidential election.

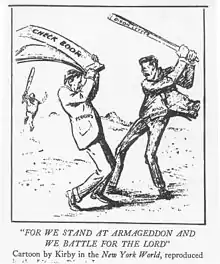

Roosevelt grew frustrated with Taft's conservatism and belatedly tried to win the 1912 Republican nomination for president. He failed, walked out, and founded the new Progressive Party. He ran in the 1912 presidential election and the split allowed the Democratic nominee Woodrow Wilson to win the election. Following the defeat, Roosevelt led a four-month expedition to the Amazon basin where he nearly died of tropical disease. During World War I, he criticized Wilson for keeping the country out of the war, and his offer to lead volunteers to France was rejected. Roosevelt considered running for president again in 1920, but his health continued to deteriorate and he died in 1919. Polls of historians and political scientists rank him as one of the greatest presidents in American history.

Early life and family

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. was born on October 27, 1858, at 28 East 20th Street in Manhattan, New York City.[5] He was the second of four children born to socialite Martha Stewart Bulloch and businessman and philanthropist Theodore Roosevelt Sr. He had an older sister (Anna), a younger brother (Elliott) and a younger sister (Corinne).[6] Elliott was later the father of Anna Eleanor Roosevelt who married Theodore's distant cousin, Franklin Delano Roosevelt. His paternal grandfather was of Dutch descent;[7] his other ancestry included primarily Scottish and Scots-Irish, English[8] and smaller amounts of German, Welsh, and French.[9] Theodore Sr. was the fifth son of businessman Cornelius Van Schaack "C. V. S." Roosevelt and Margaret Barnhill as well as a brother of Robert Roosevelt and James A. Roosevelt. Theodore's fourth cousin, James Roosevelt I, who was also a businessman, was the father of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Martha was the younger daughter of Major James Stephens Bulloch and Martha P. "Patsy" Stewart.[10] Through the Van Schaacks, Roosevelt was a descendant of the Schuyler family.[11]

Roosevelt's youth was largely shaped by his poor health and debilitating asthma. He repeatedly experienced sudden nighttime asthma attacks that caused the experience of being smothered to death, which terrified both Theodore and his parents. Doctors had no cure.[12] Nevertheless, he was energetic and mischievously inquisitive.[13] His lifelong interest in zoology began at age seven when he saw a dead seal at a local market; after obtaining the seal's head, Roosevelt and two cousins formed what they called the "Roosevelt Museum of Natural History". Having learned the rudiments of taxidermy, he filled his makeshift museum with animals that he killed or caught; he then studied the animals and prepared them for exhibition. At age nine, he recorded his observation of insects in a paper entitled "The Natural History of Insects".[14]

Roosevelt's father significantly influenced him. His father was a prominent leader in New York's cultural affairs; he helped to found the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and had been especially active in mobilizing support for the Union during the American Civil War, even though his in-laws included Confederate leaders. Roosevelt said, "My father, Theodore Roosevelt, was the best man I ever knew. He combined strength and courage with gentleness, tenderness, and great unselfishness. He would not tolerate in us children selfishness or cruelty, idleness, cowardice, or untruthfulness."

Family trips abroad, including tours of Europe in 1869 and 1870, and Egypt in 1872, shaped his cosmopolitan perspective.[15] Hiking with his family in the Alps in 1869, Roosevelt found that he could keep pace with his father. He had discovered the significant benefits of physical exertion to minimize his asthma and bolster his spirits.[16] Roosevelt began a heavy regime of exercise. After being manhandled by two older boys on a camping trip, he found a boxing coach to teach him to fight and strengthen his body.[17][18]

A 6-year-old Roosevelt witnessed the funeral procession of Abraham Lincoln from his grandfather Cornelius's mansion in Union Square, New York City, where he was photographed in the window along with his brother Elliott, as confirmed by his second wife, Edith, who was also present.[19]

Education

Roosevelt was homeschooled, mostly by tutors and his parents.[20] Biographer H. W. Brands argued that "The most obvious drawback to his home schooling was uneven coverage of the various areas of human knowledge."[21] He was solid in geography and bright in history, biology, French, and German; however, he struggled in mathematics and the classical languages. When he entered Harvard College on September 27, 1876, his father advised: "Take care of your morals first, your health next, and finally your studies."[22] His father's sudden death on February 9, 1878, devastated Roosevelt, but he eventually recovered and doubled his activities.[23]

His father, a devout Presbyterian, regularly led the family in prayers. While at Harvard, young Theodore emulated him by teaching Sunday School for more than three years at Christ Church in Cambridge. When the minister at Christ Church, which was an Episcopal church, eventually insisted he become an Episcopalian to continue teaching in the Sunday School, Roosevelt declined, and instead began teaching a mission class in a poor section of Cambridge.[24]

He did well in science, philosophy, and rhetoric courses but continued to struggle in Latin and Greek. He studied biology intently and was already an accomplished naturalist and a published ornithologist. He read prodigiously with an almost photographic memory.[25] While at Harvard, Roosevelt participated in rowing and boxing; he was once runner-up in an intramural boxing tournament.[26] Roosevelt was a member of the Alpha Delta Phi literary society (later the Fly Club), the Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity, and the prestigious Porcellian Club; he was also an editor of The Harvard Advocate. In 1880, Roosevelt graduated Phi Beta Kappa (22nd of 177) from Harvard with an A.B. magna cum laude. Biographer Henry F. Pringle states:

Roosevelt, attempting to analyze his college career and weigh the benefits he had received, felt that he had obtained little from Harvard. He had been depressed by the formalistic treatment of many subjects, by the rigidity, the attention to minutiae that were important in themselves, but which somehow were never linked up with the whole.[27]

After his father's death, Roosevelt had inherited $65,000 (equivalent to $1,971,069 in 2022), enough wealth on which he could live comfortably for the rest of his life.[28] Roosevelt gave up his earlier plan of studying natural science and decided to attend Columbia Law School instead, moving back into his family's home in New York City. Although Roosevelt was an able law student, he often found law to be irrational. He spent much of his time writing a book on the War of 1812.[29]

Determined to enter politics, Roosevelt began attending meetings at Morton Hall, the 59th Street headquarters of New York's 21st District Republican Association. Though Roosevelt's father had been a prominent member of the Republican Party, the younger Roosevelt made an unorthodox career choice for someone of his class, as most of Roosevelt's peers refrained from becoming too closely involved in politics. Roosevelt found allies in the local Republican Party and defeated an incumbent Republican state assemblyman tied to the political machine of Senator Roscoe Conkling closely. After his election victory, Roosevelt decided to drop out of law school, later saying, "I intended to be one of the governing class."[30]

Naval history and strategy

While at Harvard, Roosevelt began a systematic study of the role played by the United States Navy in the War of 1812.[31][32] Assisted by two uncles, he scrutinized original source materials and official U.S. Navy records, ultimately publishing The Naval War of 1812 in 1882. The book contained drawings of individual and combined ship maneuvers, charts depicting the differences in iron throw weights of cannon shot between rival forces, and analyses of the differences and similarities between British and American leadership down to the ship-to-ship level. Upon release, The Naval War of 1812 was praised for its scholarship and style, and it remains a standard study of the war.[33]

With the publication of The Influence of Sea Power upon History in 1890, Navy Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan was hailed as the world's outstanding naval theorist by the leaders of Europe immediately. Roosevelt paid very close attention to Mahan's emphasis that only a nation with the world's most powerful fleet could dominate the world's oceans, exert its diplomacy to the fullest, and defend its own borders.[34][35] He incorporated Mahan's ideas into his views on naval strategy for the remainder of his career.[36][37]

First marriage and widowerhood

In 1880, Roosevelt married socialite Alice Hathaway Lee.[38][39] Their daughter, Alice Lee Roosevelt, was born on February 12, 1884. Two days later, the new mother died of undiagnosed kidney failure that the pregnancy masked. In his diary, Roosevelt wrote a large "X" on the page and then, "The light has gone out of my life." His mother, Martha, had died of typhoid fever eleven hours earlier at 3:00 a.m., in the same house on 57th Street in Manhattan. Distraught, Roosevelt left baby Alice in the care of his sister Bamie while he grieved; he assumed custody of Alice when she was three.[40]

After the deaths of his wife and mother, Roosevelt focused on his work, specifically by re-energizing a legislative investigation into corruption of the New York City government, which arose from a concurrent bill proposing that power be centralized in the mayor's office.[41] For the rest of his life, he rarely spoke about his wife Alice and did not write about her in his autobiography.[42]

Early political career

State Assemblyman

Roosevelt was a member of the New York State Assembly (New York Co., 21st D.) in 1882, 1883, and 1884.[43] He began making his mark immediately handling in corporate corruption issues specifically.[43] He blocked a corrupt effort of financier Jay Gould to lower his taxes. Roosevelt also exposed the suspected collusion of Gould and Judge Theodore Westbrook and argued for and received approval for an investigation to proceed, aiming for the judge to be impeached. Although the investigation committee rejected the proposed impeachment, Roosevelt had exposed the potential corruption in Albany and assumed a high and positive political profile in multiple New York publications.[44]

Roosevelt's anti-corruption efforts helped him win re-election in 1882 by a margin greater than two-to-one, an achievement made even more impressive by the victory that Democratic gubernatorial candidate Grover Cleveland won in Roosevelt's district.[45] With Conkling's Stalwart faction of the Republican Party in disarray following the assassination of President James Garfield, Roosevelt won election as the Republican party leader in the state assembly. He allied with Governor Cleveland to win passage of a civil service reform bill.[46] Roosevelt won re-election a second time and sought the office of Speaker of the New York State Assembly, but Titus Sheard obtained the position in a 41 to 29 vote of the GOP caucus instead.[47][48] In his final term, Roosevelt served as Chairman of the Committee on Affairs of Cities, during which he wrote more bills than any other legislator.[49]

Presidential election of 1884

With numerous presidential hopefuls from whom to choose, Roosevelt supported Senator George F. Edmunds of Vermont, a colorless reformer. The state GOP preferred the incumbent president, New York City's Chester Arthur, known for passing the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act. Roosevelt fought for and succeeded in influencing the Manhattan delegates at the state convention in Utica. He then took control of the state convention, bargaining through the night and outmaneuvering the supporters of Arthur and James G. Blaine; consequently, he gained a national reputation as a key politician in his state.[50]

Roosevelt attended the 1884 GOP National Convention in Chicago and gave a speech convincing delegates to nominate African American John R. Lynch, an Edmunds supporter, to be the temporary chair. Roosevelt fought alongside the Mugwump reformers against Blaine. However, Blaine gained support from Arthur's and Edmunds's delegates, and won the nomination on the fourth ballot. In a crucial moment of his budding political career, Roosevelt resisted the demand of his fellow Mugwumps that he bolt from Blaine. He bragged about his one small success: "We achieved a victory in getting up a combination to beat the Blaine nominee for temporary chairman... To do this needed a mixture of skill, boldness and energy... to get the different factions to come in... to defeat the common foe."[51] He was also impressed by an invitation to speak before an audience of ten thousand, the largest crowd he had addressed up to that date. Having gotten a taste of national politics, Roosevelt felt less aspiration for advocacy on the state level; he then retired to his new "Chimney Butte Ranch" on the Little Missouri River.[52] Roosevelt refused to join other Mugwumps in supporting Grover Cleveland, the governor of New York and the Democratic nominee in the general election. He debated the pros and cons of staying loyal with his political friend, Henry Cabot Lodge. After Blaine won the nomination, Roosevelt had said carelessly that he would give "hearty support to any decent Democrat". He distanced himself from the promise, saying that it had not been meant "for publication".[53] When a reporter asked if he would support Blaine, Roosevelt replied, "That question I decline to answer. It is a subject I do not care to talk about."[54] In the end, he realized that he had to support Blaine to maintain his role in the GOP and he did so in a press release on July 19.[55] Having lost the support of many reformers, Roosevelt decided to retire from politics and move to North Dakota.[56]

Cattle rancher in Dakota

Roosevelt first visited the Dakota Territory in 1883 to hunt bison.[57] Exhilarated by the western lifestyle and with the cattle business booming in the territory, Roosevelt invested $14,000 ($439,700 in 2022) in hopes of becoming a prosperous cattle rancher. For the next several years, he shuttled between his home in New York and his ranch in Dakota.[58]

Following the 1884 United States presidential election, Roosevelt built a ranch named Elkhorn, which was 35 mi (56 km) north of the boomtown of Medora, North Dakota. Roosevelt learned to ride western style, rope, and hunt on the banks of the Little Missouri. Though he earned the respect of the authentic cowboys, they were not overly impressed.[59] However, he identified with the herdsman of history, a man he said possesses "few of the emasculated, milk-and-water moralities admired by the pseudo-philanthropists; but he does possess, to a very high degree, the stern, manly qualities that are invaluable to a nation".[60][61] He reoriented and began writing about frontier life for national magazines; he also published three books: Hunting Trips of a Ranchman, Ranch Life and the Hunting-Trail, and The Wilderness Hunter.[62]

Roosevelt successfully led efforts to organize ranchers there to address the problems of overgrazing and other shared concerns, which resulted in the formation of the Little Missouri Stockmen's Association. He felt compelled to promote conservation and was able to form the Boone and Crockett Club, whose primary goal was the conservation of large game animals and their habitats.[63] In 1886, Roosevelt served as a deputy sheriff in Billings County, North Dakota. During this time, he and two ranch hands hunted down three boat thieves.[64]

The uniquely severe U.S. winter of 1886–1887 wiped out his herd of cattle and those of his competitors and over half of his $80,000 investment ($2.61 million in 2022). [65][66] He ended his ranching life and returned to New York, where he escaped the damaging label of an ineffectual intellectual.[67]

Second marriage

On December 2, 1886, Roosevelt married his childhood friend, Edith Kermit Carow.[68] Roosevelt felt deeply troubled that his second marriage had taken place very quickly after the death of his first wife and he also faced resistance from his sisters.[69] Nonetheless, the couple married at St George's, Hanover Square, in London, England.[70] The couple had five children: Theodore "Ted" III in 1887, Kermit in 1889, Ethel in 1891, Archibald in 1894, and Quentin in 1897. They also raised Roosevelt's daughter from his first marriage, Alice, who often clashed with her stepmother.[71]

Reentering public life

Upon Roosevelt's return to New York in 1886, Republican leaders quickly approached him about running for mayor of New York City in the 1886 election.[72] Roosevelt accepted the nomination despite having little hope of winning the race against United Labor Party candidate Henry George and Democratic candidate Abram Hewitt. Roosevelt campaigned hard for the position, but Hewitt won with 41% (90,552 votes), taking the votes of many Republicans who feared George's radical policies.[73][74] George was held to 31% (68,110 votes), and Roosevelt took third place with 27% (60,435 votes). Fearing that his political career might never recover, Roosevelt turned his attention to writing The Winning of the West, a historical work tracking the westward movement of Americans; the book was a great success for Roosevelt, earning favorable reviews and selling numerous copies.[75]

Civil Service Commission

After Benjamin Harrison unexpectedly defeated Blaine for the presidential nomination at the 1888 Republican National Convention, Roosevelt gave stump speeches in the Midwest in support of Harrison.[76] On the insistence of Henry Cabot Lodge, President Harrison appointed Roosevelt to the United States Civil Service Commission, where he served until 1895.[77] While many of his predecessors had approached the office as a sinecure,[78] Roosevelt vigorously fought the spoilsmen and demanded enforcement of civil service laws.[79] The Sun then described Roosevelt as "irrepressible, belligerent, and enthusiastic".[80] Roosevelt frequently clashed with Postmaster General John Wanamaker, who handed out numerous patronage positions to Harrison supporters, and Roosevelt's attempt to force out several postal workers damaged Harrison politically.[81] Despite Roosevelt's support for Harrison's reelection bid in the presidential election of 1892, the eventual winner, Grover Cleveland, reappointed him to the same post.[82] Roosevelt's close friend and biographer, Joseph Bucklin Bishop, described his assault on the spoils system:

The very citadel of spoils politics, the hitherto impregnable fortress that had existed unshaken since it was erected on the foundation laid by Andrew Jackson, was tottering to its fall under the assaults of this audacious and irrepressible young man... Whatever may have been the feelings of the (fellow Republican party) President (Harrison)—and there is little doubt that he had no idea when he appointed Roosevelt that he would prove to be so veritable a bull in a china shop—he refused to remove him and stood by him firmly till the end of his term.[80]

New York City Police Commissioner

In 1894, a group of reform Republicans approached Roosevelt about running for Mayor of New York again; he declined, mostly due to his wife's resistance to being removed from the Washington social set. Soon after he declined, he realized that he had missed an opportunity to reinvigorate a dormant political career. He retreated to the Dakotas for a time; his wife Edith regretted her role in the decision and vowed that there would be no repeat of it.[83]

William Lafayette Strong, a reform-minded Republican, won the 1894 mayoral election and offered Roosevelt a position on the board of the New York City Police Commissioners.[76][84] Roosevelt became president of the board of commissioners and radically reformed the police force. Roosevelt implemented regular inspections of firearms and annual physical exams, appointed recruits based on their physical and mental qualifications rather than political affiliation, established Meritorious Service Medals, and closed corrupt police hostelries. During his tenure, a Municipal Lodging House was established by the Board of Charities, and Roosevelt required officers to register with the Board; he also had telephones installed in station houses.[85]

In 1894, Roosevelt met Jacob Riis, the muckraking Evening Sun newspaper journalist who was opening the eyes of New Yorkers to the terrible conditions of the city's millions of poor immigrants with such books as How the Other Half Lives. Riis described how his book affected Roosevelt:

When Roosevelt read [my] book, he came... No one ever helped as he did. For two years we were brothers in (New York City's crime-ridden) Mulberry Street. When he left I had seen its golden age... There is very little ease where Theodore Roosevelt leads, as we all of us found out. The lawbreaker found it out who predicted scornfully that he would "knuckle down to politics the way they all did", and lived to respect him, though he swore at him, as the one of them all who was stronger than pull... that was what made the age golden, that for the first time a moral purpose came into the street. In the light of it everything was transformed.[86]

Roosevelt made a habit of walking officers' beats late at night and early in the morning to make sure that they were on duty.[87] He made a concerted effort to uniformly enforce New York's Sunday closing law; in this, he ran up against boss Tom Platt as well as Tammany Hall—he was notified that the Police Commission was being legislated out of existence. His crackdowns led to protests and demonstrations. Invited to one large demonstration, not only did he surprisingly accept, but he also delighted in the insults, caricatures, and lampoons directed at him, and earned some good will.[88] Roosevelt chose to defer rather than split with his party.[89] As Governor of New York State, he would later sign an act replacing the Police Commission with a single Police Commissioner.[90]

Emergence as a national figure

Assistant Secretary of the Navy

.jpg.webp)

In the 1896 presidential election, Roosevelt backed Speaker of the House Thomas Brackett Reed for the Republican nomination, but William McKinley won the nomination and defeated William Jennings Bryan in the general election.[91] Roosevelt strongly opposed Bryan's free silver platform, viewing many of Bryan's followers as dangerous fanatics. He gave scores of campaign speeches for McKinley.[92] Urged by Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, President McKinley appointed Roosevelt as the Assistant Secretary of the Navy in 1897.[93] Secretary of the Navy John D. Long was more concerned about formalities than functions, was in poor health, and left many major decisions to Roosevelt. Influenced by Alfred Thayer Mahan, Roosevelt called for a build-up in the country's naval strength, particularly the construction of battleships.[94] Roosevelt also began pressing his national security views regarding the Pacific and the Caribbean on McKinley and was particularly adamant that Spain be ejected from Cuba.[95] He explained his priorities to one of the Navy's planners in late 1897:

I would regard war with Spain from two viewpoints: first, the advisability on the grounds both of humanity and self-interest of interfering on behalf of the Cubans, and of taking one more step toward the complete freeing of America from European dominion; second, the benefit done our people by giving them something to think of which is not material gain, and especially the benefit done our military forces by trying both the Navy and Army in actual practice.[96]

On February 15, 1898, USS Maine, an armored cruiser, exploded in the harbor of Havana, Cuba, killing hundreds of crew members. While Roosevelt and many other Americans blamed Spain for the explosion, McKinley sought a diplomatic solution.[97] Without approval from Long or McKinley, Roosevelt sent out orders to several naval vessels, directing them to prepare for war.[97][98] George Dewey, who had received an appointment to lead the Asiatic Squadron with the backing of Roosevelt, later credited his victory at the Battle of Manila Bay to Roosevelt's orders.[99] After finally giving up hope of a peaceful solution, McKinley asked Congress to declare war upon Spain, beginning the Spanish–American War.[100]

War in Cuba

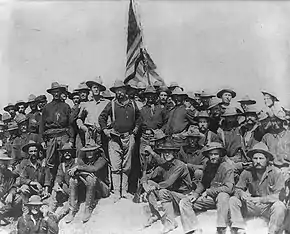

With the beginning of the Spanish–American War in late April 1898, Roosevelt resigned from his post as Assistant Secretary of the Navy. Along with Army Colonel Leonard Wood, he formed the First U.S. Volunteer Cavalry Regiment.[101] His wife and many of his friends begged Roosevelt to remain in his post in Washington, but Roosevelt was determined to see battle. When the newspapers reported the formation of the new regiment, Roosevelt and Wood were flooded with applications from all over the country.[102] Referred to by the press as the "Rough Riders", the regiment was one of many temporary units active only for the duration of the war.[103]

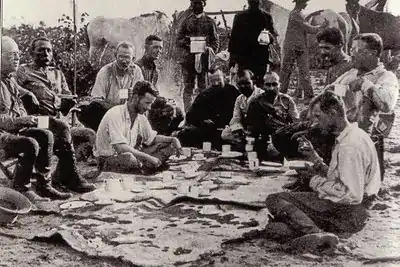

The regiment trained for several weeks in San Antonio, Texas, and in his autobiography, Roosevelt wrote that his prior experience with the New York National Guard had been invaluable, in that it enabled him to immediately begin teaching his men basic soldiering skills.[104] The Rough Riders used some standard issue gear and some of their own design, purchased with gift money. Diversity characterized the regiment, which included Ivy Leaguers, professional and amateur athletes, upscale gentlemen, cowboys, frontiersmen, Native Americans, hunters, miners, prospectors, former soldiers, tradesmen, and sheriffs. The Rough Riders were part of the cavalry division commanded by former Confederate general Joseph Wheeler, which itself was one of three divisions in the V Corps under Major General William Rufus Shafter. Roosevelt and his men landed in Daiquirí, Cuba, on June 23, 1898, and marched to Siboney. Wheeler sent parts of the 1st and 10th Regular Cavalry on the lower road northwest and sent the "Rough Riders" on the parallel road running along a ridge up from the beach. To throw off his infantry rival, Wheeler left one regiment of his Cavalry Division, the 9th, at Siboney so that he could claim that his move north was only a limited reconnaissance if things went wrong. Roosevelt was promoted to colonel and took command of the regiment when Wood was put in command of the brigade. The Rough Riders had a short, minor skirmish known as the Battle of Las Guasimas; they fought their way through Spanish resistance and, together with the Regulars, forced the Spaniards to abandon their positions.[105]

Under Roosevelt's leadership, the Rough Riders became famous for the charge up Kettle Hill on July 1, 1898, while supporting the regulars. Roosevelt had the only horse and rode back and forth between rifle pits at the forefront of the advance up Kettle Hill, an advance that he urged despite the absence of any orders from superiors. He was forced to walk up the last part of Kettle Hill because his horse had been entangled in barbed wire. The victories came at a cost of 200 killed and 1,000 wounded.[106]

In August, Roosevelt and other officers demanded that the soldiers be returned home. Roosevelt always recalled the Battle of Kettle Hill (part of the San Juan Heights) as "the great day of my life" and "my crowded hour". In 2001, Roosevelt was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions;[107] he had been nominated during the war, but Army officials, annoyed at his grabbing the headlines, blocked it.[108] After returning to civilian life, Roosevelt preferred to be known as "Colonel Roosevelt" or "The Colonel", though "Teddy" remained much more popular with the public, even though Roosevelt openly despised that moniker. Men working closely with Roosevelt customarily called him "Colonel" or "Theodore".[109]

Governor of New York

After leaving Cuba in August 1898, the Rough Riders were transported to a camp at Montauk Point, Long Island, where Roosevelt and his men were briefly quarantined due to the War Department's fear of spreading yellow fever.[110] Sister Regina Purtell was one of the nurses sent to this camp, and she was so competent during outbreaks and so beloved by the Rough Riders that she became friends with Roosevelt himself; a few years later he would ask for her to personally care for him when he was in St. Vincent's hospital.[111] Shortly after Roosevelt's return to the United States, Republican Congressman Lemuel E. Quigg, a lieutenant of party boss Tom Platt, asked Roosevelt to run in the 1898 gubernatorial election. Prospering politically from the Platt machine, Roosevelt's gradual rise to power was marked by the pragmatic decisions of New York machine boss T. C. "Tom" Platt, who served as a U.S. senator from the state.[112][113] The demonstrated willingness of Platt to compromise with the GOP progressive wing led by Roosevelt and Benjamin B. Odell Jr., resulted, over time, in their growth of political strength at the expense of the "easy boss," whose machine faced collapse in 1903 at the hands of Odell.[114] Platt disliked Roosevelt personally, feared that Roosevelt would oppose Platt's interests in office, and was reluctant to propel Roosevelt to the forefront of national politics. However, Platt also needed a strong candidate due to the unpopularity of the incumbent Republican governor, Frank S. Black. Roosevelt agreed to become the nominee and to try not to "make war" with the Republican establishment once in office. Roosevelt defeated Black in the Republican caucus by a vote of 753 to 218, and faced Democrat Augustus Van Wyck, a well-respected judge, in the general election.[115] Roosevelt campaigned vigorously on his war record, winning the election by a margin of just one percent.[116]

As governor, Roosevelt learned much about ongoing economic issues and political techniques that later proved valuable in his presidency. He studied the problems of trusts, monopolies, labor relations, and conservation. Chessman argues that Roosevelt's program "rested firmly upon the concept of the square deal by a neutral state". The rules for the Square Deal were "honesty in public affairs, an equitable sharing of privilege and responsibility, and subordination of party and local concerns to the interests of the state at large".[117]

By holding twice-daily press conferences—which was an innovation—Roosevelt remained connected with his middle-class political base.[118] Roosevelt successfully pushed the Ford Franchise-Tax bill, which taxed public franchises granted by the state and controlled by corporations, declaring that "a corporation which derives its powers from the State, should pay to the State a just percentage of its earnings as a return for the privileges it enjoys".[119] He rejected "boss" Thomas C. Platt's worries that this approached Bryanite Socialism, explaining that without it, New York voters might get angry and adopt public ownership of streetcar lines and other franchises.[120]

The New York state government affected many interests, and the power to make appointments to policy-making positions was a key role for the governor. Platt insisted that he be consulted on major appointments; Roosevelt appeared to comply, but then made his own decisions. Historians marvel that Roosevelt managed to appoint so many first-rate men with Platt's approval. He even enlisted Platt's help in securing reform, such as in the spring of 1899, when Platt pressured state senators to vote for a civil service bill that the secretary of the Civil Service Reform Association called "superior to any civil service statute heretofore secured in America".[121]

G. Wallace Chessman argues that as governor, Roosevelt developed the principles that shaped his presidency, especially insistence upon the public responsibility of large corporations, publicity as a first remedy for trusts, regulation of railroad rates, mediation of the conflict of capital and labor, conservation of natural resources and protection of the less fortunate members of society.[117] Roosevelt sought to position himself against the excesses of large corporations on the one hand and radical movements on the other.[122]

As the chief executive of the most populous state in the union, Roosevelt was widely considered a potential future presidential candidate, and supporters such as William Allen White encouraged him to run for president.[123] Roosevelt had no interest in challenging McKinley for the Republican nomination in 1900 and was denied his preferred post of Secretary of War. As his term progressed, Roosevelt pondered a 1904 presidential run, but was uncertain about whether he should seek re-election as governor in 1900.[124]

Vice presidency (1901)

In November 1899, Vice President Garret Hobart died of heart failure, leaving an open spot on the 1900 Republican national ticket. Though Henry Cabot Lodge and others urged him to run for vice president in 1900, Roosevelt was reluctant to take the powerless position and issued a public statement saying that he would not accept the nomination.[125] Additionally, Roosevelt was informed by President McKinley and campaign manager Mark Hanna that he was not being considered for the role of vice president due to his actions prior to the Spanish–American War. Eager to be rid of Roosevelt, Platt nonetheless began a newspaper campaign in favor of Roosevelt's nomination for the vice presidency.[126] Roosevelt attended the 1900 Republican National Convention as a state delegate and struck a bargain with Platt: Roosevelt would accept the nomination for vice president if the convention offered it to him but would otherwise serve another term as governor. Platt asked Pennsylvania party boss Matthew Quay to lead the campaign for Roosevelt's nomination, and Quay outmaneuvered Hanna at the convention to put Roosevelt on the ticket.[127] Roosevelt won the nomination unanimously.[128]

Roosevelt's vice-presidential campaigning proved highly energetic and an equal match for Democratic presidential nominee William Jennings Bryan's famous barnstorming style of campaigning. In a whirlwind campaign that displayed his energy to the public, Roosevelt made 480 stops in 23 states. He denounced the radicalism of Bryan, contrasting it with the heroism of the soldiers and sailors who fought and won the war against Spain. Bryan had strongly supported the war itself, but he denounced the annexation of the Philippines as imperialism, which would spoil America's innocence. Roosevelt countered that it was best for the Filipinos to have stability and the Americans to have a proud place in the world. With the nation basking in peace and prosperity, the voters gave McKinley an even larger victory than that which he had achieved in 1896.[129][130]

After the campaign, Roosevelt took office as vice president in March 1901. The office of vice president was a powerless sinecure and did not suit Roosevelt's aggressive temperament.[131] Roosevelt's six months as vice president were uneventful and boring for a man of action. He had no power; he presided over the Senate for a mere four days before it adjourned.[132] On September 2, 1901, Roosevelt first publicized an aphorism that thrilled his supporters: "Speak softly and carry a big stick, and you will go far."[133]

Presidency (1901–1909)

On September 6, 1901, President McKinley was attending the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York when he was shot by anarchist Leon Czolgosz. Roosevelt was vacationing in Isle La Motte, Vermont,[134] and traveled to Buffalo to visit McKinley in the hospital. It appeared that McKinley would recover, so Roosevelt resumed his vacation in the Adirondack Mountains.[135] When McKinley's condition worsened, Roosevelt again rushed back to Buffalo. McKinley died on September 14, and Roosevelt was informed while he was in North Creek; he continued on to Buffalo and was sworn in as the nation's 26th president at the Ansley Wilcox House.[136]

McKinley's supporters were nervous about the new president, and Ohio Senator Mark Hanna was particularly bitter that the man he had opposed so vigorously at the convention had succeeded McKinley. Roosevelt assured party leaders that he intended to adhere to McKinley's policies, and he retained McKinley's Cabinet. Nonetheless, Roosevelt sought to position himself as the party's undisputed leader, seeking to bolster the role of the president and position himself for the 1904 election.[137]

Shortly after taking office, Roosevelt invited Booker T. Washington to dinner at the White House. This sparked a bitter, and at times vicious, reaction among whites across the heavily segregated South.[138] Roosevelt reacted with astonishment and protest, saying that he looked forward to many future dinners with Washington. Upon further reflection, Roosevelt wanted to ensure that this had no effect on political support in the white South, and further dinner invitations to Washington were avoided;[139] their next meeting was scheduled as typical business at 10:00 a.m. instead.[140]

Domestic policies: The Square Deal

Trust busting and regulation

For his aggressive use of the 1890 Sherman Antitrust Act, compared to his predecessors, Roosevelt was hailed as the "trust-buster".[141] Roosevelt viewed big business as a necessary part of the American economy and sought only to prosecute the "bad trusts" that restrained trade and charged unfair prices.[142] He brought 44 antitrust suits, breaking up the Northern Securities Company, the largest railroad monopoly; and regulating Standard Oil, the largest oil company.[143][141] Presidents Benjamin Harrison, Grover Cleveland, and William McKinley combined had prosecuted only 18 antitrust violations under the Sherman Antitrust Act.[141]

Bolstered by his party's winning large majorities in the 1902 elections, Roosevelt proposed the creation of the United States Department of Commerce and Labor, which would include the Bureau of Corporations. While Congress was receptive to the Department of Commerce and Labor, it was more skeptical of the antitrust powers that Roosevelt sought to endow within the Bureau of Corporations. Roosevelt successfully appealed to the public to pressure Congress, and Congress overwhelmingly voted to pass Roosevelt's version of the bill.[144]

In a moment of frustration, House Speaker Joseph Gurney Cannon commented on Roosevelt's desire for executive branch control in domestic policymaking: "That fellow at the other end of the avenue wants everything from the birth of Christ to the death of the devil." Biographer Brands states, "Even his friends occasionally wondered whether there wasn't any custom or practice too minor for him to try to regulate, update or otherwise improve."[145] In fact, Roosevelt's willingness to exercise his power included attempted rule changes in the game of football; at the U.S. Naval Academy, he sought to force retention of martial arts classes and to revise disciplinary rules. He even ordered changes made in the minting of a coin whose design he disliked and ordered the Government Printing Office to adopt simplified spellings for a core list of 300 words, according to reformers on the Simplified Spelling Board. He was forced to rescind the latter after substantial ridicule from the press and a resolution of protest from the U.S. House of Representatives.[146]

Coal strike

In May 1902, anthracite coal miners went on strike, threatening a national energy shortage. After threatening the coal operators with intervention by federal troops, Roosevelt won their agreement to dispute arbitration by a commission, which succeeded in stopping the strike. The accord with J. P. Morgan resulted in the miners getting more pay for fewer hours, but with no union recognition.[147][148] Roosevelt said, "My action on labor should always be considered in connection with my action as regards capital, and both are reducible to my favorite formula—a square deal for every man."[149] Roosevelt was the first president to help settle a labor dispute.[150]

Prosecuted misconduct

During Roosevelt's second year in office, it was discovered there was corruption in the Indian Service, the Land Office, and the Post Office Department. Roosevelt investigated and prosecuted corrupt Indian agents who had cheated the Creeks and various Native American tribes out of land parcels. Land fraud and speculation were found involving Oregon federal timberlands. In November 1902, Roosevelt and Secretary Ethan A. Hitchcock forced Binger Hermann, the General Land Office Commissioner, to resign from office. On November 6, 1903, Francis J. Heney was appointed special prosecutor and obtained 146 indictments involving an Oregon Land Office bribery ring. U.S. Senator John H. Mitchell was indicted for bribery to expedite illegal land patents, found guilty in July 1905, and sentenced to six months in prison.[151] More corruption was found in the Postal Department, that brought on the indictments of 44 government employees on charges of bribery and fraud.[152] Historians generally agree that Roosevelt moved "quickly and decisively" to prosecute misconduct in his administration.[153]

Railroads

Merchants complained that some railroad rates were too high. In the 1906 Hepburn Act, Roosevelt sought to give the Interstate Commerce Commission the power to regulate rates, but the Senate, led by conservative Nelson Aldrich, fought back. Roosevelt worked with the Democratic Senator Benjamin Tillman to pass the bill. Roosevelt and Aldrich ultimately reached a compromise that gave the ICC the power to replace existing rates with "just-and-reasonable" maximum rates, but allowed railroads to appeal to the federal courts on what was "reasonable".[154][155] In addition to rate-setting, the Hepburn Act also granted the ICC regulatory power over pipeline fees, storage contracts, and several other aspects of railroad operations.[156]

Pure food and drugs

Roosevelt responded to public anger over the abuses in the food packing industry by pushing Congress to pass the Meat Inspection Act of 1906 and the Pure Food and Drug Act. Though conservatives initially opposed the bill, Upton Sinclair's The Jungle, published in 1906, helped galvanize support for reform.[157] The Meat Inspection Act of 1906 banned misleading labels and preservatives that contained harmful chemicals. The Pure Food and Drug Act banned food and drugs that were impure or falsely labeled from being made, sold, and shipped. Roosevelt also served as honorary president of the American School Hygiene Association from 1907 to 1908, and in 1909 he convened the first White House Conference on the Care of Dependent Children.[158]

Conservation

.jpg.webp)

Of all Roosevelt's achievements, he was proudest of his work in the conservation of natural resources and extending federal protection to land and wildlife.[159] Roosevelt worked closely with Interior Secretary James Rudolph Garfield and Chief of the United States Forest Service Gifford Pinchot to enact a series of conservation programs that often met with resistance from Western members of Congress, such as Charles William Fulton.[160] Nonetheless, Roosevelt established the United States Forest Service, signed into law the creation of five National Parks, and signed the 1906 Antiquities Act, under which he proclaimed 18 new U.S. National Monuments. He also established the first 51 bird reserves, four game preserves, and 150 National Forests. The area of the United States that he placed under public protection totals approximately 230 million acres (930,000 square kilometers).[161] In part due to his dedication to conservation, Roosevelt was voted in as the first honorary member of the Camp-Fire Club of America.[162]

Roosevelt extensively used executive orders on a number of occasions to protect forest and wildlife lands during his tenure as president.[163] By the end of his second term in office, Roosevelt used executive orders to establish 150 million acres (600,000 square kilometers) of reserved forestry land.[164] Roosevelt was unapologetic about his extensive use of executive orders to protect the environment, despite the perception in Congress that he was encroaching on too many lands.[164] Eventually, Senator Charles Fulton (R-OR) attached an amendment to an agricultural appropriations bill that effectively prevented the president from reserving any further land.[164] Before signing that bill into law, Roosevelt used executive orders to establish an additional 21 forest reserves, waiting until the last minute to sign the bill into law.[165] In total, Roosevelt used executive orders to establish 121 forest reserves in 31 states.[165] Prior to Roosevelt, only one president had issued over 200 executive orders, Grover Cleveland (253). The first 25 presidents issued a total of 1,262 executive orders; Roosevelt issued 1,081.[166]

Business panic of 1907

In 1907, Roosevelt faced the greatest domestic economic crisis since the Panic of 1893. Wall Street's stock market entered a slump in early 1907, and many investors blamed Roosevelt's regulatory policies for the decline in stock prices.[167] Roosevelt helped calm the crisis by meeting on November 4, 1907, with the leaders of U.S. Steel and approving their plan to purchase a Tennessee steel company near bankruptcy—its failure would ruin a major New York bank. He thus approved the growth of one of the largest and most hated trusts, while the public announcement calmed the markets.[168]

Roosevelt exploded in anger at the super-rich for the economic malfeasance, calling them "malefactors of great wealth". in a major speech in August entitled, "The Puritan Spirit and the Regulation of Corporations". Trying to restore confidence, he blamed the crisis primarily on Europe, but then, after saluting the unbending rectitude of the Puritans, he went on:[169]

It may well be that the determination of the government...to punish certain malefactors of great wealth, has been responsible for something of the trouble; at least to the extent of having caused these men to combine to bring about as much financial stress as possible, in order to discredit the policy of the government and thereby secure a reversal of that policy, so that they may enjoy unmolested the fruits of their own evil-doing.

Regarding the very wealthy, Roosevelt privately scorned, "...their entire unfitness to govern the country, and ... the lasting damage they do by much of what they think are the legitimate big business operations of the day".[170]

Foreign policy

Japan

The American annexation of Hawaii in 1898 was stimulated in part by fear that otherwise Japan would dominate or seize the Hawaiian Republic.[171] Similarly, Germany was the alternative to American takeover of the Philippines in 1900, and Tokyo strongly preferred the U.S. to take over. As the U.S. became a naval world power, it needed to find a way to avoid a military confrontation in the Pacific with Japan.[172]

In the 1890s, Roosevelt had been an ardent imperialist and vigorously defended the permanent acquisition of the Philippines in the 1900 campaign. After the local insurrection ended in 1902, Roosevelt wished to have a strong U.S. presence in the region as a symbol of democratic values, but he did not envision any new acquisitions. One of Roosevelt's priorities during his presidency and afterwards, was the maintenance of friendly relations with Japan.[173][174] From 1904 to 1905 Japan and Russia were at war. Both sides asked Roosevelt to mediate a peace conference, held successfully in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Roosevelt won the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts.[175]

Though he proclaimed that the United States would be neutral during the Russo-Japanese War, Roosevelt secretly favored Imperial Japan to emerge victorious against the Russian Empire. He wanted the influence of the Russians to weaken in order to take them out in the Pacific diplomatic equation, with the Japanese emerging to their spot as the Russian replacement.[176]

In California, anti-Japanese hostility was growing, and Tokyo protested. Roosevelt negotiated a "Gentleman's Agreement" in 1907. It ended explicit discrimination against the Japanese, and Japan agreed not to allow unskilled immigrants into the United States.[177] The Great White Fleet of American battleships visited Japan in 1908 during its round-the-world tour. Roosevelt intended to emphasize the superiority of the American fleet over the smaller Japanese navy, but instead of resentment the visitors arrived to a joyous welcome by Japanese elite as well as the general public. This good-will facilitated the Root–Takahira Agreement of November 1908 which reaffirmed the status quo of Japanese control of Korea and American control of the Philippines.[178] [179]

Europe

Success in the war against Spain and the new empire, plus having the largest economy in the world, meant that the United States had emerged as a world power.[180] Roosevelt searched for ways to win recognition for the position abroad.[181]

Roosevelt also played a major role in mediating the First Moroccan Crisis by calling the Algeciras Conference, which averted war between France and Germany.[182]

Roosevelt's presidency saw the strengthening of ties with Great Britain. The Great Rapprochement had begun with British support of the United States during the Spanish–American War, and it continued as Britain withdrew its fleet from the Caribbean in favor of focusing on the rising German naval threat.[183] In 1901, Britain and the United States signed the Hay–Pauncefote Treaty, abrogating the Clayton–Bulwer Treaty, which had prevented the United States from constructing a canal connecting the Pacific and the Atlantic Ocean.[184] The long-standing Alaska boundary dispute was settled on terms favorable to the United States, as Great Britain was unwilling to alienate the United States over what it considered to be a secondary issue. As Roosevelt later put it, the resolution of the Alaskan boundary dispute "settled the last serious trouble between the British Empire and ourselves."[185]

Latin America and Panama Canal

As president, he primarily focused the nation's overseas ambitions on the Caribbean, especially locations that had a bearing on the defense of his pet project, the Panama Canal.[186] Roosevelt also increased the size of the navy, and by the end of his second term the United States had more battleships than any other country besides Britain. The Panama Canal, when it opened in 1914, allowed the U.S. Navy to rapidly move back and forth from the Pacific to the Caribbean to European waters.[187]

In December 1902, the Germans, British, and Italians blockaded the ports of Venezuela in order to force the repayment of delinquent loans. Roosevelt was particularly concerned with the motives of German Emperor Wilhelm II. He succeeded in getting the three nations to agree to arbitration by tribunal at The Hague, and successfully defused the crisis.[188] The latitude granted to the Europeans by the arbiters was in part responsible for the "Roosevelt Corollary" to the Monroe Doctrine, which the President issued in 1904: "Chronic wrongdoing or an impotence which results in a general loosening of the ties of civilized society, may in America, as elsewhere, ultimately require intervention by some civilized nation, and in the Western Hemisphere, the adherence of the United States to the Monroe doctrine may force the United States, however reluctantly, in flagrant cases of such wrongdoing or impotence, to the exercise of an international police power."[189]

The pursuit of an isthmus canal in Central America during this period focused on two possible routes—Nicaragua and Panama, which was then a rebellious district within Colombia. Roosevelt convinced Congress to approve the Panamanian alternative, and a treaty was approved, only to be rejected by the Colombian government. When the Panamanians learned of this, a rebellion followed, was supported by Roosevelt, and succeeded. A treaty with the new Panama government for construction of the canal was then reached in 1903.[190] Roosevelt received criticism for paying the bankrupt Panama Canal Company and the New Panama Canal Company $40,000,000 (equivalent to $13.03 billion in 2022) for the rights and equipment to build the canal.[153] Critics charged that an American investor syndicate allegedly divided the large payment among themselves. There was also controversy over whether a French company engineer influenced Roosevelt in choosing the Panama route for the canal over the Nicaragua route. Roosevelt denied charges of corruption concerning the canal in a January 8, 1906, message to Congress. In January 1909, Roosevelt, in an unprecedented move, brought criminal libel charges against the New York World and the Indianapolis News known as the "Roosevelt-Panama Libel Cases".[191] Both cases were dismissed by U.S. District Courts, and on January 3, 1911, the U.S. Supreme Court, upon federal appeal, upheld the lower courts' rulings.[192] Historians are sharply critical of Roosevelt's criminal prosecutions of the World and the News but are divided on whether actual corruption in acquiring and building the Panama Canal took place.[193]

In 1906, following a disputed election, an insurrection ensued in Cuba; Roosevelt sent Taft, the Secretary of War, to monitor the situation; he was convinced that he had the authority to unilaterally authorize Taft to deploy Marines, if necessary, without congressional approval.[194]

Examining the work of numerous scholars, Ricard (2014) reports that:

The most striking evolution in the twenty-first-century historiography of Theodore Roosevelt is the switch from a partial arraignment of the imperialist to a quasi-unanimous celebration of the master diplomatist.... [Recent works] have underlined cogently Roosevelt's exceptional statesmanship in the construction of the nascent twentieth-century "special relationship". ...The twenty-sixth president's reputation as a brilliant diplomatist and real politician has undeniably reached new heights in the twenty-first century...yet, his Philippine policy still prompts criticism.[195]

On November 6, 1906, Roosevelt was the first president to depart the continental United States on an official diplomatic trip. Roosevelt made a 17-day trip to Panama and Puerto Rico. Roosevelt checked on the progress of the Canal's construction and talked to workers about the importance of the project. In Puerto Rico, he recommended that Puerto Ricans become U.S. citizens.[196][197]

Media

Building on McKinley's effective use of the press, Roosevelt made the White House the center of news every day, providing interviews and photo opportunities. After noticing the reporters huddled outside the White House in the rain one day, he gave them their own room inside, effectively inventing the presidential press briefing. The grateful press, with unprecedented access to the White House, rewarded Roosevelt with ample coverage.[198]

Roosevelt normally enjoyed very close relationships with the press, which he used to keep in daily contact with his middle-class base. While out of office, he made a living as a writer and magazine editor. He loved talking with intellectuals, authors, and writers. He drew the line, however, at exposé-oriented scandal-mongering journalists who, during his term, sent magazine subscriptions soaring by their attacks on corrupt politicians, mayors, and corporations. Roosevelt himself was not usually a target, but a speech of his from 1906 coined the term "muckraker" for unscrupulous journalists making wild charges. "The liar", he said, "is no whit better than the thief, and if his mendacity takes the form of slander he may be worse than most thieves."[199]

The press did briefly target Roosevelt in one instance. After 1904, he was periodically criticized for the manner in which he facilitated the construction of the Panama Canal. According to biographer Brands, Roosevelt, near the end of his term, demanded that the U.S. Justice Department bring charges of criminal libel against Joseph Pulitzer's New York World. The publication had accused him of "deliberate misstatements of fact" in defense of family members who were criticized as a result of the Panama affair. Though an indictment was obtained, the case was ultimately dismissed in federal court—it was not a federal offense, but one enforceable in state courts. The Justice Department had predicted that result and had also advised Roosevelt accordingly.[200]

Election of 1904

The control and management of the Republican Party lay in the hands of Ohio Senator and Republican Party chairman Mark Hanna until McKinley's death. Roosevelt and Hanna frequently cooperated during Roosevelt's first term, but Hanna left open the possibility of a challenge to Roosevelt for the 1904 Republican nomination. Roosevelt and Ohio's other Senator, Joseph B. Foraker, forced Hanna's hand by calling for Ohio's state Republican convention to endorse Roosevelt for the 1904 nomination.[201] Unwilling to break with the president, Hanna was forced to publicly endorse Roosevelt. Hanna and Pennsylvania Senator Matthew Quay both died in early 1904, and with the waning of Thomas Platt's power, Roosevelt faced little effective opposition for the 1904 nomination.[202] In deference to Hanna's conservative loyalists, Roosevelt at first offered the party chairmanship to Cornelius Bliss, but he declined. Roosevelt turned to his own man, George B. Cortelyou of New York, the first Secretary of Commerce and Labor. To buttress his hold on the party's nomination, Roosevelt made it clear that anyone opposing Cortelyou would be considered to be opposing the President.[203] The President secured his own nomination, but his preferred vice-presidential running mate, Robert R. Hitt, was not nominated.[204] Senator Charles Warren Fairbanks of Indiana, a favorite of conservatives, gained the nomination.[202]

While Roosevelt followed the tradition of incumbents in not actively campaigning on the stump, he sought to control the campaign's message through specific instructions to Cortelyou. He also attempted to manage the press's release of White House statements by forming the Ananias Club. Any journalist who repeated a statement made by the president without approval was penalized by restriction of further access.[205]

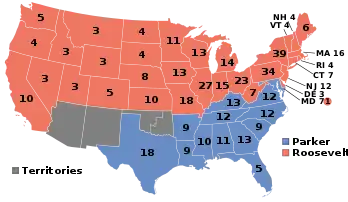

The Democratic Party's nominee in 1904 was Alton Brooks Parker. Democratic newspapers charged that Republicans were extorting large campaign contributions from corporations, putting ultimate responsibility on Roosevelt, himself.[206] Roosevelt denied corruption while at the same time he ordered Cortelyou to return $100,000 (equivalent to $3.3 million in 2022) of a campaign contribution from Standard Oil.[207] Parker said that Roosevelt was accepting corporate donations to keep damaging information from the Bureau of Corporations from going public.[207] Roosevelt strongly denied Parker's charge and responded that he would "go into the Presidency unhampered by any pledge, promise, or understanding of any kind, sort, or description...".[208] Allegations from Parker and the Democrats, however, had little impact on the election, as Roosevelt promised to give every American a "square deal".[208] Roosevelt won 56% of the popular vote, and Parker received 38%; Roosevelt also won the Electoral College vote, 336 to 140. Before his inauguration ceremony, Roosevelt declared that he would not serve another term.[209] Democrats afterwards would continue to charge Roosevelt and the Republicans of being influenced by corporate donations during Roosevelt's second term.[210]

Second term

As his second term progressed, Roosevelt moved to the left of his Republican Party base and called for a series of reforms, most of which Congress failed to pass.[211] In his last year in office, he was assisted by his friend Archibald Butt (who later perished in the sinking of RMS Titanic).[212] Roosevelt's influence waned as he approached the end of his second term, as his promise to forego a third term made him a lame duck and his concentration of power provoked a backlash from many Congressmen.[213] He sought a national incorporation law (at a time when all corporations had state charters), called for a federal income tax (despite the Supreme Court's ruling in Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co.), and an inheritance tax. In the area of labor legislation, Roosevelt called for limits on the use of court injunctions against labor unions during strikes; injunctions were a powerful weapon that mostly helped business. He wanted an employee liability law for industrial injuries (pre-empting state laws) and an eight-hour work day for federal employees. In other areas he also sought a postal savings system (to provide competition for local banks), and he asked for campaign reform laws.[214]

The election of 1904 continued to be a source of contention between Republicans and Democrats. A Congressional investigation in 1905 revealed that corporate executives donated tens of thousands of dollars in 1904 to the Republican National Committee. In 1908, a month before the general presidential election, Governor Charles N. Haskell of Oklahoma, former Democratic Treasurer, said that Senators beholden to Standard Oil lobbied Roosevelt, in the summer of 1904, to authorize the leasing of Indian oil lands by Standard Oil subsidiaries. He said Roosevelt overruled his Secretary of the Interior Ethan A. Hitchcock and granted a pipeline franchise to run through the Osage lands to the Prairie Oil and Gas Company. The New York Sun made a similar accusation and said that Standard Oil, a refinery who financially benefited from the pipeline, had contributed $150,000 to the Republicans in 1904 (equivalent to $4.9 million in 2022) after Roosevelt's alleged reversal allowing the pipeline franchise. Roosevelt branded Haskell's allegation as "a lie, pure and simple" and obtained a denial from Treasury Secretary Shaw that Roosevelt had neither coerced Shaw nor overruled him.[215]

Rhetoric of righteousness

Roosevelt's rhetoric was characterized by an intense moralism of personal righteousness.[216][217][218] The tone was typified by his denunciation of "predatory wealth" in a message he sent Congress in January 1908 calling for passage of new labor laws:

Predatory wealth--of the wealth accumulated on a giant scale by all forms of iniquity, ranging from the oppression of wageworkers to unfair and unwholesome methods of crushing out competition, and to defrauding the public by stock jobbing and the manipulation of securities. Certain wealthy men of this stamp, whose conduct should be abhorrent to every man of ordinarily decent conscience, and who commit the hideous wrong of teaching our young men that phenomenal business success must ordinarily be based on dishonesty, have during the last few months made it apparent that they have banded together to work for a reaction. Their endeavor is to overthrow and discredit all who honestly administer the law, to prevent any additional legislation which would check and restrain them, and to secure if possible a freedom from all restraint which will permit every unscrupulous wrongdoer to do what he wishes unchecked provided he has enough money....The methods by which the Standard Oil people and those engaged in the other combinations of which I have spoken above have achieved great fortunes can only be justified by the advocacy of a system of morality which would also justify every form of criminality on the part of a labor union, and every form of violence, corruption, and fraud, from murder to bribery and ballot box stuffing in politics.[219]

Post-presidency (1909–1919)

Election of 1908

Roosevelt enjoyed being president and was still relatively youthful but felt that a limited number of terms provided a check against dictatorship. Roosevelt ultimately decided to stick to his 1904 pledge not to run for a third term. He personally favored Secretary of State Elihu Root as his successor, but Root's ill health made him an unsuitable candidate. New York Governor Charles Evans Hughes loomed as a potentially strong candidate and shared Roosevelt's progressivism, but Roosevelt disliked him and considered him to be too independent. Instead, Roosevelt settled on his Secretary of War, William Howard Taft, who had ably served under Presidents Harrison, McKinley, and Roosevelt in various positions. Roosevelt and Taft had been friends since 1890, and Taft had consistently supported President Roosevelt's policies.[220] Roosevelt was determined to install the successor of his choice, and wrote the following to Taft: "Dear Will: Do you want any action about those federal officials? I will break their necks with the utmost cheerfulness if you say the word!". Just weeks later he branded as "false and malicious" the charge that he was using the offices at his disposal to favor Taft.[221] At the 1908 Republican convention, many chanted for "four years more" of a Roosevelt presidency, but Taft won the nomination after Henry Cabot Lodge made it clear that Roosevelt was not interested in a third term.[222]

In the 1908 election, Taft easily defeated the Democratic nominee, three-time candidate William Jennings Bryan. Taft promoted a progressivism that stressed the rule of law; he preferred that judges rather than administrators or politicians make the basic decisions about fairness. Taft usually proved to be a less adroit politician than Roosevelt and lacked the energy and personal magnetism, along with the publicity devices, the dedicated supporters, and the broad base of public support that made Roosevelt so formidable. When Roosevelt realized that lowering the tariff would risk creating severe tensions inside the Republican Party by pitting producers (manufacturers, industrial workers, and farmers) against merchants and consumers, he stopped talking about the issue. Taft ignored the risks and tackled the tariff boldly, encouraging reformers to fight for lower rates, and then cutting deals with conservative leaders that kept overall rates high. The resulting Payne-Aldrich tariff of 1909, signed into law early in President Taft's tenure, was too high for most reformers, and Taft's handling of the tariff alienated all sides. While the crisis was building inside the Party, Roosevelt was touring Africa and Europe, to allow Taft space to be his own man.[223]

Africa and Europe (1909–1910)

In March 1909, the ex-president left the country for the Smithsonian-Roosevelt African Expedition, a safari in east and central Africa.[224] Roosevelt's party landed in Mombasa, East Africa (now Kenya) and traveled to the Belgian Congo (now Democratic Republic of the Congo) before following the Nile River to Khartoum in modern Sudan. Well-financed by Andrew Carnegie and by his own writings, Roosevelt's large party hunted for specimens for the Smithsonian Institution and for the American Museum of Natural History in New York.[225] The group, led by the hunter-tracker R.J. Cunninghame, included scientists from the Smithsonian, and was joined from time to time by Frederick Selous, the famous big game hunter and explorer. Participants on the expedition included Kermit Roosevelt, Edgar Alexander Mearns, Edmund Heller, and John Alden Loring.[226]

The team killed or trapped 11,400 animals,[225] from insects and moles to hippopotamuses and elephants. The 1,000 large animals included 512 big game animals, including six rare white rhinos. Tons of salted carcases and skins were shipped to Washington; it took years to mount them all, and the Smithsonian shared duplicate specimens with other museums. Regarding the large number of animals taken, Roosevelt said, "I can be condemned only if the existence of the National Museum, the American Museum of Natural History, and all similar zoological institutions are to be condemned".[227] He wrote a detailed account of the safari in the book African Game Trails, recounting the excitement of the chase, the people he met, and the flora and fauna he collected in the name of science.[228]

After his safari, Roosevelt traveled north to embark on a tour of Europe. Stopping first in Egypt, he commented favorably on British rule of the region, giving his opinion that Egypt was not yet ready for independence.[229] He refused a meeting with the Pope due to a dispute over a group of Methodists active in Rome. He met with Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria-Hungary, Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, King George V of Great Britain, and other European leaders. In Oslo, Norway, Roosevelt delivered a speech calling for limitations on naval armaments, a strengthening of the Permanent Court of Arbitration, and the creation of a "League of Peace" among the world powers.[230] He also delivered the Romanes Lecture at Oxford, in which he denounced those who sought parallels between the evolution of animal life and the development of society.[231] Though Roosevelt attempted to avoid domestic politics, he quietly met with Gifford Pinchot, who related his own disappointment with the Taft Administration.[232] Pinchot had been forced to resign as head of the forest service after clashing with Taft's Interior Secretary, Richard Ballinger, who had prioritized development over conservation. Roosevelt returned to the United States in June 1910[233] where he was shortly thereafter honored with a reception luncheon on the roof of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York City hosted by the Camp-Fire Club of America, of which he was a member.[234]

In October 1910, Roosevelt became the first U.S. president to fly in an airplane, staying aloft for four minutes in a Wright Brothers-designed craft near St. Louis, Missouri.[235]

Republican Party schism

Roosevelt had attempted to refashion Taft into a copy of himself, but he recoiled as Taft began to display his individuality. He was offended on election night when Taft indicated that his success had been possible not just through the efforts of Roosevelt, but also Taft's half-brother Charles P. Taft. Roosevelt was further alienated when Taft, intent on becoming his own man, did not consult him about cabinet appointments.[236] Roosevelt and other progressives were ideologically dissatisfied over Taft's conservation policies and his handling of the tariff when he concentrated more power in the hands of conservative party leaders in Congress.[237] Stanley Solvick argues that as President Taft abided by the goals and procedures of the "Square Deal" promoted by Roosevelt in his first term. The problem was that Roosevelt and the more radical progressives had moved on to more aggressive goals, such as curbing the judiciary, which Taft rejected.[238] Regarding radicalism and liberalism, Roosevelt wrote a British friend in 1911:

- Fundamentally it is the radical liberal with whom I sympathize. He is at least working toward the end for which I think we should all of us strive; and when he adds sanity in moderation to courage and enthusiasm for high ideals he develops into the kind of statesman whom alone I can wholeheartedly support.[239]

Roosevelt urged progressives to take control of the Republican Party at the state and local level and to avoid splitting the party in a way that would hand the presidency to the Democrats in 1912. To that end Roosevelt publicly expressed optimism about the Taft Administration after meeting with the president in June 1910.[240]

In August 1910, Roosevelt escalated the rivalry with a speech at Osawatomie, Kansas, which was the most radical of his career. It marked his public break with Taft and the conservative Republicans. Advocating a program he called the "New Nationalism", Roosevelt emphasized the priority of labor over capital interests, and the need to control corporate creation and combination. He called for a ban on corporate political contributions.[241] Returning to New York, Roosevelt began a battle to take control of the state Republican party from William Barnes Jr., Tom Platt's successor as the state party boss. Taft had pledged his support to Roosevelt in this endeavor, and Roosevelt was outraged when Taft's support failed to materialize at the 1910 state convention.[242] Roosevelt campaigned for the Republicans in the 1910 elections, in which the Democrats gained control of the House for the first time since 1892. Among the newly elected Democrats was New York state senator Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who argued that he represented his distant cousin's policies better than his Republican opponent.[243]