Ahl al-Bayt

Ahl al-Bayt (Arabic: أَهْل ٱلْبَيْت, lit. 'people of the house') refers to the family of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, but the term has also been extended in Sunni Islam to all descendants of the Banu Hashim (Muhammad's clan) and even to all Muslims.[1][2] In Shia Islam, the term is limited to Muhammad, his daughter Fatima, his cousin and son-in-law Ali ibn Abi Talib, and their two sons, Ḥasan and Husayn. A common Sunni view adds the wives of Muhammad to these five.[3]

| Part of a series on |

| Muhammad |

|---|

|

While all Muslims revere the Ahl al-Bayt,[4][5] it is the Shia Muslims who hold the Ahl al-Bayt in the highest esteem, regarding them as the rightful leaders of the Muslim community after Muhammad. The Twelver Shias also believe in the redemptive power of the pain and martyrdom endured by the members of the Ahl al-Bayt, particularly Husayn.[2][4]

Definition

When ahl (أهل) appears in construction with a person, it refers to his blood relatives. However, the word also acquires wider meanings with other nouns.[6] In particular, bayt (بَيْت) is translated as 'habitation' and 'dwelling',[7] and thus the basic translation of ahl al-bayt is '(the) inhabitants of the house'.[6] That is, ahl al-bayt literally translates to '(the) people of the house'. In the absence of the definite article al-, the literal translation of ahl bayt is 'household'.[6]

Other prophets

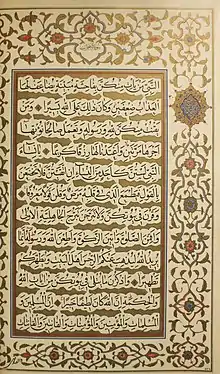

The phrase ahl al-bayt appears three times in the Quran, the central religious text of Islam, in relation to Abraham (11:73), Moses (28:12), and Muhammad (33:33).[6] For Abraham and Moses, ahl al-bayt in the Quran is unanimously interpreted as family.[6] Yet merit is also a criterion of membership in a prophet's family in the Quran.[7] That is, pagan or disloyal members of the families of the past prophets are not excluded from God's punishment.[1][8] In particular, Noah's family is saved from the deluge, except his wife and one of his sons, about whom Noah's plea was rejected according to verse 11:46, "O Noah, he [your son] is not of your family (ahl)."[9] Families of the past prophets are often given a prominent role in the Quran.[10] Therein, their kin are selected by God as the spiritual and material heirs to the prophets.[11][12]

Muhammad

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

The household of Muhammad, often referred to as the Ahl al-Bayt, appear in verse 33:33 of the Quran,[13] also known as the verse of purification.[14] The last passage of the verse of purification reads, "God only desires to remove defilement from you, O ahl al-bayt, and to purify you completely."[13] Muslims disagree as to who belongs to Muhammad's ahl al-bayt and what privileges or responsibilities they have.[1]

Inclusion of the Ahl al-Kisa

The majority of the traditions quoted by the Sunni exegete al-Tabari (d. 923) identify the Ahl al-Bayt with the Ahl al-Kisa, namely, Muhammad, his daughter Fatima, her husband Ali, and their two sons, Hasan and Husayn.[15][16][17] Such reports are also cited in Sahih Muslim, Sunnan al-Tirmidhi, Musnad Ahmad ibn Hanbal,[18][19] all canonical Sunni collections of hadith, and by some other Sunni authorities, including al-Suyuti (d. 1505), al-Hafiz al-Kabir,[20] al-Hakim al-Nishapuri (d. 1014),[21] and Ibn Kathir (d. 1373).[22]

In possibly the earliest version of the hadith of the kisa,[23] Muhammad's wife Umm Salama relates that he gathered Ali, Fatima, Hasan, and Husayn under his cloak and prayed, "O God, these are my ahl al-bayt and my closest family members; remove defilement from them and purify them completely."[6][1] Some accounts continue that Umm Salama then asked Muhammad, "Am I with thee, O Messenger of God?" but received the negative response, "Thou shalt obtain good. Thou shalt obtain good." Among others, such reports are given in Sunnan al-Tirmidhi, Musnad Ahmad ibn Hanbal,[24] and by Ibn Kathir, al-Suyuti, and the Shia exegete Muhammad H. Tabatabai (d. 1981).[13] Yet another Sunni version of this hadith appends Umm Salama to the Ahl al-Bayt.[3] In another Sunni version, Muhammad's servant Wathila bint al-Asqa' is also counted in the Ahl al-Bayt.[25]

Elsewhere in Musnad Ahmad ibn Hanbal, Muhammad is said to have recited the last passage in the verse of purification every morning when he passed by Fatima's house to remind her household of the morning prayer.[26][27] In his mubahala (lit. 'mutual cursing') with a delegation of Najrani Christians, Muhammad is also believed to have gathered the above four under his cloak and referred to them as his ahl al-bayt, according to Shia and some Sunni sources,[28][17] including Sahih Muslim and Sunan al-Tirmidhi.[29] This makeup of the Ahl al-Bayt is echoed by the Islamicist Laura Veccia Vaglieri (d. 1989),[26] and also reported unanimously in Shia sources.[3] In Shia theology works, the Ahl al-Bayt often also includes the remaining Shia imams.[15] The term is sometimes loosely applied in Shia writings to all descendants of Ali and Fatima.[15][30][31]

Inclusion of Muhammad's wives

Perhaps because the earlier injunctions in the verse of purification are addressed at Muhammad's wives,[1] some Sunni authors, such as al-Wahidi (d. 1075), have exclusively interpreted the Ahl al-Bayt as Muhammad's wives.[15][6] Others have noted that the last passage of this verse is grammatically inconsistent with the previous injunctions (masculine plural versus feminine plural pronouns).[32] Thus the Ahl al-Bayt is not or is not limited to Muhammad's wives.[13][1][26] Ibn Kathir, for instance, includes Ali, Fatima, and their two sons in the Ahl al-Bayt, in addition to Muhammad's wives.[15] Indeed, certain Sunni hadiths support the inclusion of Muhammad's wives in the Ahl al-Bayt, including some reports on the authority of Ibn Abbas and Ikrima, two early Muslim figures.[33]

Alternatively, the Islamicist Oliver Leaman proposes that marriage to a prophet does not guarantee inclusion in his ahl al-bayt. He argues that, in verse 11:73,[6] Sara is included in Abraham's ahl al-bayt only after receiving the news of her imminent motherhood to two prophets, Isaac and Jacob. Likewise, Leaman suggests that Moses' mother is counted as a member of ahl al-bayt in verse 28:12, not for being married to Imran, but for being the mother of Moses.[7] Similarly, in their bid for inclusion in the Ahl al-Bayt, the Abbasids argued that women, noble and holy as they may be, could not be considered a source of pedigree (nasab). As the descendants of Muhammad's paternal uncle Abbas, they claimed that he was equal to Muhammad's father after the latter died.[6][34]

Broader interpretations

As hinted above, some Sunni authors have broadened its application to include in the Ahl al-Bayt the clan of Muhammad (Banu Hashim),[6][4] the Banu Muttalib,[3] the Abbasids,[13][6][15] and even the Umayyads, who had descended from Hashim's nephew Umayya.[1][15] Indeed, another Sunni version of the Hadith al-Kisa is evidently intended to append the Abbasids to the Ahl al-Bayt.[15] This Abbasid claim was in turn the cornerstone of their bid for legitimacy.[6][1] Similarly, a Sunni version of the hadith of the thaqalayn defines the Ahl al-Bayt as the descendants of Ali and his brothers (Aqil and Jafar), and Muhammad's uncle Abbas.[3][15]

The first two Rashidun caliphs, Abu Bakr and Umar, have also been included in the Ahl al-Bayt in some Sunni reports, as they were both fathers-in-law of Muhammad. Nevertheless, these and the accounts about the inclusion of the Umayyads in the Ahl al-Bayt might have been later reactions to the Abbasid claims to inclusion in the Ahl al-Bayt and their own bid for legitimacy.[1] The term has also been interpreted as the Meccan tribe of Quraysh,[6][1] or the whole Muslim community.[3][1] For instance, the Islamicist Rudi Paret (d. 1983) identifies bayt (lit. 'house') in the verse of purification with the Kaaba, located in the holiest site in Islam. However, his theory has only found few supporters, notably Moshe Sharon, another expert.[6][1][35]

Conclusion

A typical Sunni compromise is to define the Ahl al-Bayt as the Ahl al-Kisa (Muhammad, Ali, Fatima, Hasan, Husayn) together with Muhammad's wives,[3] which might also reflect the majority opinion of medieval Sunni exegetes.[36] Among modern Islamicists, this view is shared by Ignác Goldziher (d. 1921) and his coauthors,[15] and mentioned by Sharon,[6] while Wilferd Madelung (d. 2023) also includes the Banu Hashim in the Ahl al-Bayt in view of their blood relation to Muhammad.[33] In contrast, Shia limits the Ahl al-Bayt to Muhammad, Ali, Fatima, Hasan, and Husayn, pointing to authentic traditions in Sunni and Shia sources.[37][7][32] Their view is supported by Veccia Vaglieri and Husain M. Jafri (d. 2019), another expert.[26]

Place in Islam

In the Quran

Families and descendants of the past prophets hold a prominent position in the Quran. Therein, their descendants become spiritual and material heirs to keep their fathers' covenants intact.[38][39] Muhammad's kin are also mentioned in the Quran in various contexts.[40]

Verse of the mawadda

Known as the verse of the mawadda (lit. 'affection' or 'love'), verse 42:23 of the Quran contains the passage, "[O Mohammad!] Say, 'I ask not of you any reward for it, save affection among kinsfolk.'"[41] The Shia-leaning historian Ibn Ishaq (d. 767) narrates that Muhammad specified al-qurba in this verse as Ali, Fatima, and their two sons, Hasan and Husayn.[42] This is also the view of some Sunni scholars, including al-Razi (d. 1209), Baydawi (d. 1319),[43] and Ibn al-Maghazili.[42] Most Sunni authors, however, reject the Shia view and offer various alternatives,[41] chief among them is that this verse enjoins love for kinsfolk in general.[44][45] In Twelver Shia, the love in the verse of the mawadda also entails obedience to the Ahl al-Bayt as the source of exoteric and esoteric religious guidance.[5][46]

Verse of the mubahala

A Christian envoy from Najran, located in South Arabia, arrived in Medina circa 632 and negotiated a peace treaty with Muhammad.[47][48] During their stay, the two parties may have also debated the nature of Jesus, human or divine, although the delegation ultimately rejected the Islamic belief,[49] which acknowledges the miraculous birth of Jesus but dismisses the Christians' belief in his divinity.[50] Linked to this ordeal is verse 3:61 of the Quran.[51] This verse instructs Muhammad to challenge his opponents to mubahala (lit. 'mutual cursing'),[32] perhaps when the debate had reached a deadlock.[52]

And to whosoever disputes with thee over it, after the knowledge that has come unto thee, say, "Come! Let us call upon our sons and your sons, our women and your women, ourselves and yourselves. Then let us pray earnestly, so as to place the curse of God upon those who lie."[51]

The delegation withdrew from the challenge and negotiated for peace.[48] The majority of reports indicate that Muhammad appeared for the occasion of the mubahala, accompanied by Ali, Fatima, Hasan, and Husayn.[53] Such reports are given by Ibn Ishaq,[54] al-Razi,[54] Muslim ibn al-Hajjaj (d. 875), Hakim al-Nishapuri,[55] and Ibn Kathir.[56] The inclusion of these four relatives by Muhammad, as his witnesses and guarantors in the mubahala ritual,[57][58] must have raised their religious rank within the community.[49][59] If the word 'ourselves' in this verse is a reference to Ali and Muhammad, as Shia authors argue, then the former naturally enjoys a similar religious authority in the Quran as the latter.[60][61]

Khums

The Quran also reserves for Muhammad's kin a fifth (khums) of booty and a part of fay. The latter comprises lands and properties conquered peacefully by Muslims.[44] This Quranic directive is seen as compensation for the exclusion of Muhammad and his family from alms (sadaqa, zakat). Indeed, almsgiving is considered an act of purification for ordinary Muslims and their donations should not reach Muhammad's kin as that would violate their state of purity in the Quran.[62]

Hadith of the thaqalayn

The hadith of the thaqalayn (lit. 'two treasures') is a widely-reported prophetic hadith that introduces the Quran and the progeny of Muhammad as the only two sources of divine guidance after his death.[28] This hadith is of particular significance in Twelver Shia, where the Twelve Imams, all descendants of Muhammad, are viewed as his spiritual and political successors.[63] The version that appears in Musnad Ahmad, a canonical Sunni hadith collection, reads,

I [Muhammad] left among you two treasures which, if you cling to them, you shall not be led into error after me. One of them is greater than the other: The book of God (Quran), which is a rope stretched from Heaven to Earth, and [the second one is] my progeny, my Ahl al-Bayt. These two shall not be parted until they return to the pool [of abundance in paradise, kawthar].[28]

Hadith of the ark

The hadith of the ark is attributed to Muhammad and likens his household to Noah's ark. Reported by both Shia and Sunni authorities, the version presented in al-Mustadrak, a Sunni collection of prophetic traditions, reads,[64] "Truly the people of my house (Ahl al-Bayt) in my community is like Noah's ark: Whoever takes refuge therein is saved and whoever opposes it is drowned."[65]

In Muslim communities

The sanctity of a prophet's family was likely an accepted principle at the time of Muhammad.[66] Today, all Muslims venerate the household of Muhammad,[4][2][5] and blessings on his family (āl) are invoked in every prayer.[67] In many Muslim communities, high social status is granted to people claiming descent from Ali and Fatima. They are called sayyids or sharifs.[31][4][30] Several Muslim heads of state and politicians have also claimed blood descent from Muhammad, including the Alawid dynasty of Morocco, the Hashimite dynasty of Iraq and of Jordan, and the leader of the Iranian revolution, Khomeini.[4]

Sunnis too revere the Ahl al-Bayt,[4] perhaps more so before modern times.[1] Most Sufi tariqs (brotherhoods) also trace their spiritual chain to Muhammad through Ali and revere the Ahl al-Kisa as the Holy Five.[4] It is, however, the (Twelver and Isma'ili) Shias who hold the Ahl al-Bayt in the highest esteem, regarding them as the rightful leaders of the Muslim community after Muhammad. They also believe in the redemptive power of the pain and martyrdom endured by the Ahl al-Bayt (particularly by Husayn) for those who empathize with their divine cause and suffering.[2][4] Twelver Shias await the messianic advent of Muhammad al-Mahdi, a descendant of Muhammad, who is expected to usher in an era of peace and justice by overcoming tyranny and oppression on earth.[68][4] Some Shia sources also ascribe cosmological importance to the Ahl al-Bayt, where they are viewed as the reason for the creation.[3]

See also

- Brothers of Jesus, a Christian analogue

- Family tree of Muhammad

- Children of Muhammad

Footnotes

- Brunner 2014.

- Campo 2009.

- Goldziher, Arendonk & Tritton 2012.

- Campo 2004.

- Mavani 2013, p. 41.

- Sharon.

- Leaman 2006.

- Madelung 1997, p. 10.

- Madelung 1997, pp. 9, 10.

- Madelung 1997, p. 8.

- Madelung 1997, p. 17.

- Jafri 1979, pp. 14–16.

- Nasr et al. 2015, p. 2331.

- Abbas 2021, p. 65.

- Howard 1984.

- Madelung 1997, pp. 14–15.

- Algar 2011.

- Momen 1985, pp. 16–7, 325.

- Shomali 2003, pp. 58–59, 62–63.

- Mavani 2013, p. 71.

- Shah-Kazemi 2007, p. 61n17.

- Lalani 2000, pp. 69, 147.

- Soufi 1997, p. 6.

- Shomali 2003, p. 62.

- Soufi 1997, pp. 7–8.

- Veccia Vaglieri 2012.

- Shomali 2003, p. 63.

- Momen 1985, p. 16.

- Momen 1985, pp. 16, 325.

- Esposito 2003, p. 9.

- Glassé 2001.

- Haider 2014, p. 35.

- Madelung 1997, p. 15.

- Jafri 1979, p. 195.

- Madelung 1997, p. 11.

- Soufi 1997, p. 16.

- Momen 1985, pp. 16, 17.

- Madelung 1997, pp. 8–12.

- Jafri 1979, pp. 15–17.

- Madelung 1997, p. 12.

- Nasr et al. 2015, p. 2691.

- Mavani 2013, pp. 41, 60.

- Momen 1985, p. 152.

- Madelung 1997, p. 13.

- Gril.

- Lalani 2000, p. 66.

- Momen 1985, pp. 13–14.

- Schmucker 2012.

- Madelung 1997, p. 16.

- Nasr et al. 2015, pp. 378–379.

- Nasr et al. 2015, p. 379.

- Osman 2015, p. 110.

- Haider 2014, p. 36.

- Shah-Kazemi 2015.

- Osman 2015, p. 140n42.

- Nasr et al. 2015, p. 380.

- McAuliffe.

- Fedele 2018, p. 56.

- Lalani 2006, p. 29.

- Mavani 2013, p. 72.

- Bill & Williams 2002, p. 29.

- Madelung 1997, p. 14.

- Tabatabai 1975, p. 156.

- Momen 1985, p. 325.

- Sobhani 2001, p. 112.

- Jafri 1979, p. 17.

- Soufi 1997, pp. 16–17.

- Mavani 2013, p. 240.

References

- Abbas, H. (2021). The Prophet's Heir: The Life of Ali Ibn Abi Talib. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300252057.

- Algar, H. (2011). "Āl-e 'Abā". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Vol. I/7. p. 742.

- Bill, J.; Williams, J.A. (2002). Roman Catholics and Shi'i Muslims: Prayer, Passion, and Politics. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0807826898.

- Brunner, R. (2014). "Ahl al-Bayt". In Fitzpatrick, C.; Walker, A.H. (eds.). Muhammad in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopedia of the Prophet of God. pp. 5–9.

- Campo, J.E. (2004). "Ahl al-Bayt". In Martin, R.C. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim world. Vol. 1. Macmillan Reference. pp. 25–26. ISBN 0028656040.

- Campo, J.E., ed. (2009). "ahl al-bayt". Encyclopedia of Islam. Facts On File. p. 23. ISBN 9780816054541.

- Esposito, J.L., ed. (2003). The Oxford Dictionary of Islam. Oxford University Press. p. 9. ISBN 0195125584.

- Fedele, V. (2018). "Fatima (605/615–632 CE)". In de-Gaia, S. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Women in World Religions: Faith and Culture Across History. ABC-CLIO. p. 56. ISBN 9781440848506.

- Glassé, C. (2001). "Ahl al-Bayt". The New Encyclopedia of Islam. Altamira. p. 31. ISBN 0759101892.

- Goldziher, I.; Arendonk, C. van; Tritton, A.S. (2012). "Ahl Al-Bayt". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (Second ed.). ISBN 9789004161214.

- Gril, D. "Love and Affection". In Pink, J. (ed.). Encyclopaedia of the Qur'ān. doi:10.1163/1875-3922_q3_EQSIM_00266.

- Haider, N. (2014). Shī'ī Islam: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107031432.

- Howard, I.K.A. (1984). "Ahl-e Bayt". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Vol. I/6. p. 365.

- Jafri, S.H.M (1979). Origins and Early Development of Shia Islam. London: Longman.

- Lalani, A.R. (2000). Early Shi'i Thought: The Teachings of Imam Muhammad al-Baqir. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1850435928.

- Lalani, A.R. (2006). "'Ali ibn Abi Talib". In Leaman, O. (ed.). The Qur'an: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 28–32. ISBN 9780415326391.

- Leaman, O. (2006). "Ahl al-Bayt". In Leaman, O. (ed.). The Qur'an: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 16–17. ISBN 9780415326391.

- Madelung, W. (1997). The Succession to Muhammad: A Study of the Early Caliphate. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521646963.

- Mavani, H. (2013), Religious Authority and Political Thought in Twelver Shi'ism: From Ali to Post-Khomeini, Routledge Studies in Political Islam, Routledge, ISBN 9780415624404

- McAuliffe, J.D. "Fāṭima". In Pink, J. (ed.). Encyclopaedia of the Qur'ān. doi:10.1163/1875-3922_q3_EQSIM_00153. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- Momen, M. (1985). An Introduction to Shi'i Islam. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300035315.

- Nasr, S.H.; Dagli, C.K.; Dakake, M.M.; Lumbard, J.E.B.; Rustom, M., eds. (2015). The Study Quran: A New Translation and Commentary. Harper Collins. ISBN 9780061125867.

- Osman, R. (2015). Female Personalities in the Qur'an and Sunna: Examining the Major Sources of Imami Shi'i Islam. Routledge. ISBN 9781315770147.

- Schmucker, W. (2012). "Mubāhala". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (Second ed.). doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_5289. ISBN 9789004161214.

- Shah-Kazemi, R. (2007). Justice and Remembrance: Introducing the Spirituality of Imam 'Ali. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 9781845115265.

- Shah-Kazemi, R. (2015). "'Alī b. Abī Ṭālib 2. Biography". In Daftary, F. (ed.). Encyclopaedia Islamica. Translated by Melvin-Koushki, M. doi:10.1163/1875-9831_isla_COM_0252.

- Sharon, M. "People of the House". In Pink, J. (ed.). Encyclopaedia of the Qur'ān. Retrieved 16 July 2023.

- Shomali, M.A. (2003). Shi'i Islam: Origins, Faith, and Practices. Islammic College for Advanced Studies Press. ISBN 190406311X.

- Sobhani, J. (2001). Doctrines of Shi'i Islam: A Compendium of Imami Beliefs and Practices. Translated by Shah-Kazemi, R. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1860647804. LCCN 2004433965. OCLC 48944249. OL 17038817M.

- Soufi, D.L. (1997). The Image of Fāṭima in Classical Muslim Thought (PhD thesis). Princeton University. ProQuest 304390529.

- Tabatabai, S.M.H. (1975). Shi'ite Islam. Translated by Nasr, S.H. State University of New York Press. ISBN 0873953908.

- Veccia Vaglieri, L. (2012). "Fāṭima". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (Second ed.). ISBN 9789004161214.

Further reading

- Öz, M. (1994). "Ehl-i Beyt". Turkish Encyclopedia of Islam (in Turkish). Vol. 10. TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi. pp. 498–501. ISBN 9789753894371.