Al-Muwaffaq

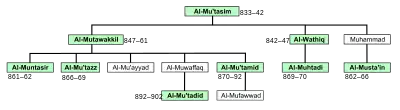

Abu Ahmad Talha ibn Ja'far (Arabic: أبو أحمد طلحة بن جعفر; 29 November 843 – 2 June 891), better known by his laqab as Al-Muwaffaq Billah (Arabic: الموفق بالله, lit. 'Blessed of God'[2]), was an Abbasid prince and military leader, who acted as the de facto regent of the Abbasid Caliphate for most of the reign of his brother, Caliph al-Mu'tamid. His stabilization of the internal political scene after the decade-long "Anarchy at Samarra", his successful defence of Iraq against the Saffarids and the suppression of the Zanj Rebellion restored a measure of the Caliphate's former power and began a period of recovery, which culminated in the reign of al-Muwaffaq's own son, the Caliph al-Mu'tadid.

| Abu Ahmad Talha ibn Ja'far al-Muwaffaq bi-Allah أبو أحمد طلحة بن جعفر الموفق بالله | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regent (de facto) of the Abbasid Caliphate | |||||

| Office | June 870 – 2 June 891 | ||||

| Caliph | Al-Mu'tamid | ||||

| Born | 29 November 843 Samarra, Abbasid Caliphate | ||||

| Died | 2 June 891[1] Baghdad, Abbasid Caliphate | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Consort | Dirar | ||||

| Successor | al-Mu'tadid | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Abbasid | ||||

| Father | al-Mutawakkil | ||||

| Mother | Umm Ishaq | ||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||

| Military career | |||||

| Allegiance | Abbasid Caliphate | ||||

| Service/ | Abbasid Army | ||||

| Years of service | 891 (end of active service) | ||||

| Rank | Commander-in-Chief | ||||

| Battles/wars | Battle of Dayr al-'Aqul, Zanj Rebellion Kharijite Rebellion | ||||

| Relations | al-Muntasir (brother) al-Musta'in (cousin) al-Mu'tazz (brother) al-Muhtadi (cousin) al-Mu'tamid (brother) | ||||

Early life

Talha, commonly known by the teknonym Abu Ahmad, was born on 29 November 843, as the son of the Caliph Ja'far al-Mutawakkil (r. 847–861) and a Greek slave concubine, Eshar, known as Umm Ishaq.[3][4] In 861, he was present in his father's murder at Samarra by the Turkish military slaves (ghilman): the historian al-Tabari reports that he had been drinking with his father that night, and came upon the assassins while going to the toilet, but after a brief attempt to protect the caliph, he retired to his own rooms when he realized that his efforts were futile.[5] The murder was almost certainly instigated by al-Mutawakkil's son and heir, al-Muntasir, who immediately ascended the throne;[6] nevertheless Abu Ahmad's own role in the affair is suspect as well, given his close ties later on with the Turkish military leaders. According to historian Hugh Kennedy, "it is possible, therefore, that Abu Ahmad had already had close links with the young Turks before the murder, or that they were forged on that night".[5] This murder opened a period of internal upheaval known as the "Anarchy at Samarra", where the Turkish military chiefs vied with other powerful groups, and with each other, over control of the government and its financial resources.[7][8]

It was during this period of turmoil, in February 865, that Caliph al-Musta'in (r. 862–866) and two of the senior Turkish officers, Wasif and Bugha the Younger, fled from Samarra to the old Abbasid capital, Baghdad, where they could count on the support of the city's Tahirid governor, Muhammad ibn Abdallah. The Turkish army in Samarra then selected al-Musta'in's brother al-Mu'tazz (r. 866–869) as Caliph, and Abu Ahmad was entrusted with the conduct of operations against al-Musta'in and his supporters. The ensuing siege of Baghdad lasted from February to December 865. In the end, Abu Ahmad and Muhammad ibn Abdallah reached a negotiated settlement, which would see al-Musta'in abdicate. As a result, on 25 January 866, al-Mu'tazz was acclaimed as caliph in the Friday prayer in Baghdad. Contrary to the agreed terms, however, al-Musta'in was murdered.[9][10] It was most likely during this time that Abu Ahmad consolidated his relationship with the Turkish military, especially with Musa ibn Bugha, who played a crucial role during the siege.[3][5] Abu Ahmad further solidified these ties when he secured a pardon for Bugha the Younger.[5][11]

On his return to Samarra, Abu Ahmad was initially received with honour by the Caliph, but six months later he was thrown into prison as a potential rival, along with another of his brothers, al-Mu'ayyad. The latter was soon executed, but Abu Ahmad survived thanks to the protection of the Turkish military. Eventually, he was released and exiled to Basra before being allowed to return to Baghdad, where he was forced to reside at the Qasr al-Dinar palace in East Baghdad.[10][5] He was so popular there that at the time of al-Mu'tazz's death in July 869, the army and the people clamoured in favour of his elevation to the caliphate, rather than al-Muhtadi (r. 869–870). Al-Muwaffaq refused, however, and took the oath of allegiance to al-Muhtadi.[10][5]

Regent of the Caliphate

At the time al-Muhtadi was killed by the Turks in June 870, Abu Ahmad was at Mecca. Immediately he hastened north to Samarra, where he and Musa ibn Bugha effectively sidelined the new Caliph, al-Mu'tamid (r. 870–892), and assumed control of the government.[3][5]

In his close relations with the Turkish military, and his active participation in military affairs, al-Muwaffaq differed from most Abbasid princes of his time, and resembles rather his grandfather, Caliph al-Mu'tasim (r. 833–842).[12][13] Like al-Mu'tasim, this relationship was to be the foundation of al-Muwaffaq's power: when the Turkish rank and file demanded that one of the Caliph's brothers to be appointed as their commander—bypassing their own leaders, who were accused of misappropriating salaries—al-Muwaffaq was appointed the main intermediary between the caliphal government and the Turkish military. In return for the Turks' loyalty, he apparently abolished the other competing corps of the caliphal army such as the Maghariba or the Faraghina, which are no longer mentioned after c. 870.[11][14] Hugh Kennedy sums up the arrangement thus: "al-Muwaffaq assured their status and their position as the army of the caliphate and al-Muwaffaq's role in the civil administration meant that they received their pay".[15] Al-Muwaffaq's close personal relationship with the Turkish military leadership—initially Musa ibn Bugha, as well as Kayghalagh and Ishaq ibn Kundaj after Musa's death in 877—his own prestige as a prince of the dynasty, and the exhaustion after a decade of civil strife, allowed him to establish unchallenged control over the Turks, as indicated by their willingness to participate in costly campaigns under his leadership.[3][11]

Following the sack of Basra by the Zanj in 871, Abu Ahmad was also conferred an extensive governorship, covering most of the lands still under direct caliphal control: the Hejaz, Yemen, Iraq with Baghdad and Wasit, Basra, Ahwaz and Fars.[5][10] To denote his authority, he assumed an honorific name in the style of the caliphs, al-Muwaffaq Billah (lit. 'Blessed of God').[3][5] His power was further expanded on 20 July 875, when the Caliph included him in the line of succession after his own underage son, Ja'far al-Mufawwad, and divided the empire in two large spheres of government. The western provinces were given to al-Mufawwad, while al-Muwaffaq was given charge of the eastern ones; in practice, al-Muwaffaq continued to exercise control over the western provinces as well.[3][10][16]

With al-Mu'tamid largely confined to Samarra, al-Muwaffaq and his personal secretaries (Sulayman ibn Wahb, Sa'id ibn Makhlad, and Isma'il ibn Bulbul) effectively ruled the Caliphate from Baghdad.[3] What little autonomy al-Mu'tamid enjoyed was further curtailed after the death of the long-serving vizier Ubayd Allah ibn Yahya ibn Khaqan in 877, when al-Muwaffaq assumed the right to appoint the Caliph's viziers himself. However, it was not the viziers, but al-Muwaffaq's personal secretary Sa'id ibn Makhlad, who was the outstanding figure in the Caliphate's bureaucracy, at least until his own disgrace in 885. He was followed by Isma'il ibn Bulbul, who served concurrently as vizier to both brothers.[12]

Campaigns

"The defeat of these two formidable rebellions—and the consequent rescue of the ʾAbbásid Caliphate from an untimely extinction—was due chiefly to the energy and resource of a remarkable man, the Emir al-Muwaffaq."

Harold Bowen[17]

As the main military leader of the Caliphate, it fell upon al-Muwaffaq to meet the numerous challenges to caliphal authority that sprung up during these years. Indeed, as Michael Bonner writes, "al-Muwaffaq's decisive leadership was to save the Abbasid caliphate from destruction on more than one occasion".[13] The main military threats to the Abbasid Caliphate were the Zanj Rebellion in southern Iraq and the ambitions of Ya'qub ibn al-Layth, the founder of the Saffarid dynasty, in the east.[3][11] Al-Muwaffaq's drive and energy played a crucial role in their suppression.[17]

Confronting the Saffarids

A humble soldier, Ya'qub, surnamed al-Saffar ('the Coppersmith'), had exploited the decade-long Samarra strife to first gain control over his native Sistan, and then to expand his control. By 873 he ruled over almost all of the eastern lands of the Caliphate, ousting the hitherto dominant Tahirids from power, a move denounced by al-Muwaffaq.[18][19][20] Finally, in 875 he seized control of the province of Fars, which not only provided much of the scarce revenue for the Caliphate's coffers, but was also dangerously close to Iraq. The Abbasids tried to prevent an attack by Ya'qub by formally recognizing him as governor over all the eastern provinces and by granting him special honours, including adding his name to the Friday sermon and appointment to the influential position of sahib al-shurta (chief of police) in Baghdad. Nevertheless, in the next year Ya'qub began his advance on Baghdad, until he was confronted and decisively beaten by the Abbasids under al-Muwaffaq and Musa ibn Bugha at the Battle of Dayr al-Aqul near Baghdad. The Abbasid victory, a complete surprise to many, saved the capital.[10][21][22]

Nevertheless, the Saffarids remained firmly ensconced in their possession of most of the Iranian provinces, and in 879, even the Abbasid court had to recognize Ya'qub as governor of Fars.[23] After Ya'qub died from illness in the same year, his brother and successor, Amr ibn al-Layth, hacknowledged the Caliph's suzerainty and had been rewarded with the governorship over the eastern provinces and the position of sahib al-shurta of Baghdad—essentially the same posts the Tahirids had held—in exchange for an annual tribute of one million dirhams.[10][24] Soon Amr was having trouble asserting his authority, especially in Khurasan, where already under Ya'qub pro-Tahirid opposition had emerged, first under Ahmad ibn Abdallah al-Khujistani, and then under Rafi ibn Harthama, who challenged Saffarid rule over the province.[25]

With the Zanj subdued, after 883 al-Muwaffaq turned his attention again to the east. In 884/5, al-Muwaffaq ordered the public cursing of Amr, and appointed the Dulafid Ahmad ibn Abd al-Aziz as governor of Kirman and Fars, and the reinstated the ousted Tahirid governor, Muhammad ibn Tahir, as governor over Khurasan, with Rafi ibn Harthama as his deputy. The army under the vizier Sa'id ibn Makhlad conquered most of the province of Fars, forcing Amr himself to come west. After initial success against the caliphal general Tark ibn al-Abbas, Amr was routed by Ahmad ibn Abd al-Aziz in 886, and again in 887 by al-Muwaffaq in person. Amr's ally, Abu Talha Mansur ibn Sharkab, defected to the Abbasids, but Amr was able to retreat to Sijistan, protected from pursuit by the desert.[26]

The threat by the Tulunids and the Byzantines in the west forced al-Muwaffaq to negotiate a settlement in 888/9 that largely restored the previous status quo, with Amr recognized as governor of Khurasan, Fars, and Kirman, paying 10 million dirhams as tribute in exchange, and his agent, the Tahirid Ubaydallah ibn Abdallah ibn Tahir, sent to become sahib al-shurta of Baghdad.[27] In 890, al-Muwaffaq again attempted to take back Fars, but this time the invading Abbasid army under Ahmad ibn Abd al-Aziz was defeated, and another agreement restored peaceful relations and Amr's titles and possessions.[28]

Suppression of the Zanj Revolt

The struggle against the uprising of the Zanj slaves in the marshlands of southern Iraq—according to Michael Bonner "the greatest slave rebellion in the history of Islam"—which began in September 869, was a long and difficult conflict, and almost brought the Caliphate to is knees. Due to the Saffarid threat, the Abbasids could not fully mobilize against the Zanj until 879. Consequently, the Zanj initially held the upper hand, capturing much of lower Iraq including Basra and Wasit and defeating the Abbasid armies, which were reduced to trying to contain the Zanj advance. The balance tipped after 879, when al-Muwaffaq's son Abu'l-Abbas, the future Caliph al-Mu'tadid (r. 892–902), was given the command. Abu'l-Abbas was joined in 880 by al-Muwaffaq himself, and in a succession of engagements in the marshes of southern Iraq, the Abbasid forces drove back the Zanj towards their capital, Mukhtara, which fell in August 883.[29][30][31] Another son of al-Muwaffaq, Harun, also participated in the campaigns. He also served as nominal governor of a few provinces, but died young on 7 November 883.[32]

The victory over the Zanj was celebrated as a major triumph for al-Muwaffaq personally and for his regime: al-Muwaffaq received the victory title al-Nasir li-Din Allah ('he who upholds the Faith of God'), while his secretary Sa'id ibn Makhlad received the title Dhu'l-Wizaratayn ('holder of the two vizierates').[19]

Relations with the Tulunids

At the same time, al-Muwaffaq also had to confront the challenge posed by the ambitious governor of Egypt, Ahmad ibn Tulun. The son of a Turkish slave, Ibn Tulun had been the province's governor since the reign of al-Mu'tazz, and expanded his power further in 871, when he expelled the caliphal fiscal agent and assumed direct control of Egypt's revenue, which he used to create an army of ghilman of his own. [33][34] Preoccupied with the more immediate threats of the Saffarids and the Zanj rebels, as well as with keeping in check the Turkish troops and managing the internal tensions of the caliphal government, al-Muwaffaq was unable to react. This gave Ibn Tulun the necessary time to consolidate his own position in Egypt.[35][36]

Open conflict between Ibn Tulun and al-Muwaffaq broke out in 875/6, on the occasion of a large remittance of revenue to the central government. Counting on the rivalry between the Caliph and his over-mighty brother to maintain his own position, Ibn Tulun forwarded a larger share of the taxes to al-Mu'tamid (2.2 million gold dinars) instead of al-Muwaffaq (1.2 million dinars).[37] Al-Muwaffaq, who in his fight against the Zanj considered himself entitled to the major share of the provincial revenues, was angered by this, and by the implied machinations between Ibn Tulun and his brother. Al-Muwaffaq sought someone to replace Ibn Tulun, but all the officials in Baghdad had been bought off by the governor of Egypt, and refused. Al-Muwaffaq sent a letter to the Egyptian ruler demanding his resignation, which the latter predictably refused. Both sides geared for war. Al-Muwaffaq nominated Musa ibn Bugha as governor of Egypt and sent him with troops to Syria. Due to a combination of lack of pay and supplies for the troops, and the fear generated by Ibn Tulun's army, Musa never got further than Raqqa. After ten months of inaction and a rebellion by his troops, Musa returned to Iraq, without having achieved anything.[38][39] In a public gesture of support for al-Mu'tamid and opposition to al-Muwaffaq, Ibn Tulun assumed the title of 'Servant of the Commander of the Faithful' (mawla amir al-mu'minin) in 878.[37]

Ibn Tulun now seized the initiative. Having served in his youth in the border wars with the Byzantine Empire at Tarsus, he now requested to be conferred the command of the frontier districts of Cilicia (the Thughur). Al-Muwaffaq initially refused, but following the Byzantine successes of the previous years al-Mu'tamid prevailed upon his brother and in 877/8 Ibn Tulun received responsibility for the entirety of Syria and the Cilician frontier, which Ibn Tulun proceeded to take over in person.[40][41] Back in Egypt, however, his son Ahmad, possibly encourage by al-Muwaffaq, was preparing to usurp his father's position.[10] This was unsuccessful, and on his return to Egypt in 879, Ibn Tulun captured his son and had him imprisoned.[42] Following his return from Syria, Ibn Tulun added his own name to coins issued by the mints under his control, along with those of the Caliph and heir apparent, al-Mufawwad,[43] thus proclaiming himself as a de facto independent ruler.[33][34]

In the autumn of 882, the Tulunid general Lu'lu' defected to the Abbasids, while the new governor of Tarsus in the Cilician Thughur refused to acknowledge Tulunid suzerainty. This prompted ibn Tulun to once again move into Syria.[44] This coincided with an attempt by al-Mu'tamid to escape from Samarra and seek sanctuary with Ibn Tulun, who was in Damascus. However, the governor of Mosul, Ishaq ibn Kundajiq, acting on instructions by al-Muwaffaq, arrested the caliph and handed him back to al-Muwaffaq, who placed his brother under effective house arrest at Wasit.[45][46] This opened anew the rift between the two rulers: al-Muwaffaq nominated Ishaq ibn Kundaj as governor of Egypt and Syria—in reality a largely symbolic appointment—while Ibn Tulun organized an assembly of religious jurists at Damascus which denounced al-Muwaffaq as a usurper, condemned his maltreatment of al-Mu'tamid, declared his place in the succession as void, and called for a jihad against him. Ibn Tulun had his rival duly denounced in sermons in the mosques across the Tulunid domains, while the Abbasid regent responded in kind with a ritual denunciation of Ibn Tulun.[47] Despite the belligerent rhetoric, however, neither made moves to confront the other militarily.[43] Only in 883 did Ibn Tulun send an army to take over to take over the two holy cities of Islam, Mecca and Medina, but it was defeated by the Abbasids.[48][49]

After Ibn Tulun's death in 884, al-Muwaffaq attempted again to retake control of Egypt from Ibn Tulun's successor Khumarawayh. Khumarawayh however defeated an expedition under Abu'l-Abbas, and extended his control over most of the Jazira as well. In 886, al-Muwaffaq was forced to recognize the Tulunids as hereditary governors over Egypt and Syria for 30 years, in exchange for an annual tribute of 300,000 dinars.[48][50][51]

Final years and the succession

Towards the end of the 880s, al-Muwaffaq's relations with his son Abu'l-Abbas deteriorated, although the reason is unclear. In 889, Abu'l-Abbas was arrested and imprisoned on his father's orders, where he remained despite the demonstrations of the ghilman loyal to him. He apparently remained under arrest until May 891, when al-Muwaffaq, already nearing his death, returned to Baghdad after two years in Jibal.[3][52] By this time, the gout from which he had long suffered had incapacitated him to the extent that he could nor ride, and required a specially prepared litter. It was evident to observers that he was nearing his end.[53] The vizier Ibn Bulbul, who was opposed to Abu'l-Abbas, called al-Mu'tamid and al-Mufawwad into the city, but the popularity of Abu'l-Abbas with the troops and the populace was such that he was released from captivity and recognized as his father's heir.[54][55] Al-Muwaffaq died on 2 June, and was buried in al-Rusafah near his mother's tomb. Two days later, Abu'l-Abbas succeeded his father in his offices and received the oath of allegiance as second heir after al-Mufawwad.[1] In October 892, al-Mu'tamid died and Abu'l-Abbas al-Mu'tadid brushed aside his cousin to ascend the throne, quickly emerging as "the most powerful and effective Caliph since al-Mutawakkil" (Kennedy).[56]

References

- Fields 1987, p. 168.

- Waines 1992, p. 173 (note 484).

- Kennedy 1993, p. 801.

- Özaydın 2016, pp. 326–327.

- Kennedy 2001, p. 149.

- Bonner 2010, p. 305.

- Kennedy 2001, pp. 137–142.

- Bonner 2010, pp. 306–313.

- Kennedy 2001, pp. 135–136, 139.

- Özaydın 2016, p. 327.

- Gordon 2001, p. 142.

- Kennedy 2004, p. 174.

- Bonner 2010, p. 314.

- Kennedy 2001, pp. 149–150.

- Kennedy 2004, pp. 173–174.

- Bonner 2010, pp. 320–321.

- Bowen 1928, p. 9.

- Bonner 2010, pp. 315–316.

- Sourdel 1970, p. 129.

- Bosworth 1975, pp. 107–116.

- Bonner 2010, p. 316.

- Bosworth 1975, pp. 113–114.

- Bosworth 1975, p. 114.

- Bosworth 1975, pp. 116–117.

- Bosworth 1975, pp. 116–118.

- Bosworth 1975, pp. 118–119.

- Bosworth 1975, p. 119.

- Bosworth 1975, pp. 119–120.

- Bonner 2010, pp. 323–324.

- Kennedy 2001, pp. 153–156.

- Kennedy 2004, pp. 177–179.

- Fields 1987, pp. 34, 38–39, 144.

- Sourdel 1970, p. 130.

- Kennedy 2004, pp. 176–177.

- Hassan 1960, p. 278.

- Bianquis 1998, pp. 94–95.

- Bianquis 1998, p. 95.

- Bianquis 1998, pp. 95, 98–99.

- Hassan 1960, pp. 278–279.

- Bianquis 1998, pp. 95–96.

- Brett 2010, p. 560.

- Bianquis 1998, pp. 96–97.

- Hassan 1960, p. 279.

- Bianquis 1998, pp. 100–101.

- Bianquis 1998, p. 101.

- Kennedy 2004, pp. 174, 177.

- Bianquis 1998, pp. 101–102.

- Özaydın 2016, p. 328.

- Gordon 2000, p. 617.

- Kennedy 2004, p. 177.

- Bonner 2010, p. 335.

- Kennedy 2001, p. 152.

- Bowen 1928, pp. 25, 27.

- Kennedy 2001, pp. 152–153.

- Fields 1987, pp. 165–168.

- Kennedy 2001, p. 153.

Sources

- Bianquis, Thierry (1998). "Autonomous Egypt from Ibn Ṭūlūn to Kāfūr, 868–969". In Petry, Carl F. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Egypt, Volume 1: Islamic Egypt, 640–1517. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 86–119. ISBN 0-521-47137-0.

- Bonner, Michael (2010). "The waning of empire, 861–945". In Robinson, Chase F. (ed.). The New Cambridge History of Islam, Volume 1: The Formation of the Islamic World, Sixth to Eleventh Centuries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 305–359. ISBN 978-0-521-83823-8.

- Bosworth, C.E. (1975). "The Ṭāhirids and Ṣaffārids". In Frye, Richard N. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 4: From the Arab Invasion to the Saljuqs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 90–135. ISBN 0-521-20093-8.

- Bowen, Harold (1928). The Life and Times of ʿAlí Ibn ʿÍsà, ‘The Good Vizier’. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. OCLC 386849.

- Brett, Michael (2010). "Egypt". In Robinson, Chase F. (ed.). The New Cambridge History of Islam, Volume 1: The Formation of the Islamic World, Sixth to Eleventh Centuries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 506–540. ISBN 978-0-521-83823-8.

- Fields, Philip M., ed. (1987). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXXVII: The ʿAbbāsid Recovery: The War Against the Zanj Ends, A.D. 879–893/A.H. 266–279. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-054-0.

- Gordon, Matthew S. (2000). "Ṭūlūnids". In Bearman, P. J.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Heinrichs, W. P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume X: T–U (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 616–618. ISBN 978-90-04-11211-7.

- Gordon, Matthew S. (2001). The Breaking of a Thousand Swords: A History of the Turkish Military of Samarra (A.H. 200–275/815–889 C.E.). Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-4795-2.

- Hassan, Zaky M. (1960). "Aḥmad b. Ṭūlūn". In Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume I: A–B (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 278–279. OCLC 495469456.

- Kennedy, Hugh (1993). "al-Muwaffaḳ". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume VII: Mif–Naz (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 801. ISBN 978-90-04-09419-2.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2001). The Armies of the Caliphs: Military and Society in the Early Islamic State. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-25093-5.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2004). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century (Second ed.). Harlow: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-40525-7.

- Özaydın, Abdülkerim (2016). "Muvaffak el-Abbâsî". TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Supplement 2 (Kâfûr, Ebü'l-Misk – Züreyk, Kostantin) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies. pp. 326–328. ISBN 978-975-389-889-8.

- Sourdel, D. (1970). "The ʿAbbasid Caliphate". In Holt, P. M.; Lambton, Ann K. S.; Lewis, Bernard (eds.). The Cambridge History of Islam, Volume 1A: The Central Islamic Lands from Pre-Islamic Times to the First World War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 104–139. ISBN 978-0-521-21946-4.

- Waines, David, ed. (1992). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXXVI: The Revolt of the Zanj, A.D. 869–879/A.H. 255–265. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-0763-9.